Nuragic civilization

|

| History of Sardinia |

The Nuragic civilization,[1][2] also known as the Nuragic culture, formed in the Mediterranean island of Sardinia, Italy in the Bronze Age. According to the traditional theory put forward by Giovanni Lilliu in 1966, it developed after multiple migrations from the West of people related to the Beaker culture who conquered and disrupted the local Copper Age cultures; other scholars instead hypothesize an autochthonous origin.[3] It lasted from the 18th century BC [4] (Middle Bronze Age), or from the 23rd century BC,[5][6] up to the Roman colonization in 238 BC.[7][8][9] Others date the culture as lasting at least until the 2nd century AD,[10] and in some areas, namely the Barbagia, to the 6th century AD,[11][12] or possibly even to the 11th century AD.[6][13] Although it must be remarked that the construction of new nuraghi had already stopped by the 12th-11th century BC, during the Final Bronze Age.[14][15]

The adjective "Nuragic" is neither an autonym nor an ethnonym. It derives from the island's most characteristic monument, the nuraghe, a tower-fortress type of construction the ancient Sardinians built in large numbers starting from about 1800 BC.[16] Today, more than 7,000 nuraghes dot the Sardinian landscape.[a]

No written records of this civilization have been discovered,[19] apart from a few possible short epigraphic documents belonging to the last stages of the Nuragic civilization.[20] The only written information there comes from classical literature of the Greeks and Romans, such as Pseudo-Aristotle and Diodorus Siculus,[21] and may be considered more mythical than historical.[22]

History

[edit]Pre-Nuragic Sardinia

[edit]

In the Stone Age the island was first inhabited by people who had arrived there in the Paleolithic and Neolithic ages from Europe and the Mediterranean area. The most ancient settlements have been discovered both in central and northern Sardinia (Anglona). Several later cultures developed on the island, such as the Ozieri culture (3200−2700 BC). The economy was based on agriculture, animal husbandry, fishing, and trading with the mainland. With the diffusion of metallurgy, silver and copper objects and weapons also appeared on the island.[23]: 16 In 2014, early Chalcolithic period Sardinia was identified as one of the earliest silver extraction centres in the world.[24] This took place during the 4th millennium BC.

Remains from this period include hundreds of menhirs (called perdas fittas)[25] and dolmens, more than 2,400 hypogeum tombs called domus de Janas, the statue menhirs, representing warriors or female figures, and the stepped pyramid of Monte d'Accoddi, near Sassari, which show some similarities with the monumental complex of Los Millares (Andalusia) and the later talaiots in the Balearic Islands. According to some scholars, the similarity between this structure and those found in Mesopotamia is due to cultural influxes coming from the Eastern Mediterranean.[26][23]: 16

The altar of Monte d'Accoddi fell out of use starting from c. 2000 BC, when the Beaker culture, which at the time was widespread in almost all western Europe, appeared on the island. The beakers arrived in Sardinia from two different regions: firstly from Spain and southern France, and secondly from Central Europe, through the Italian Peninsula.[27]

Nuragic era

[edit]Early Bronze Age

[edit]

The Bonnanaro culture was the last evolution of the Beaker culture in Sardinia (c. 1800–1600 BC), and displayed several similarities with the contemporary Polada culture of northern Italy. These two cultures shared common features in the material culture such as undecorated pottery with axe-shaped handles.[28] These influences may have spread to Sardinia via Corsica, where they absorbed new architectural techniques (such as cyclopean masonry) that were already widespread on the island.[29] New peoples coming from the mainland arrived on the island at that time, bringing with them new religious philosophies, new technologies and new ways of life, making the previous ones obsolete or reinterpreting them.[30]: 362 [31]: 25–27

It is perhaps in virtue of stimuli and models (and - why not? - of some drop of blood) from the Central European and Polada-Rhone areas, that the culture of Bonnanaro I gives a jolt to the known and produces in step with the times. ... From the generally severe, practical character and essentiality of the material equipment (in particular in the ceramics without any decoration), we understand the nature and the warlike habit of the newcomers and the conflictual thrust that they give to life on the island. This is confirmed by the presence of stone and metal weapons (copper and bronze). The metal also spreads in objects of use (copper and bronze awls), and ornamental objects (bronze rings and silver foil) ... It seems to feel a fall of ideologies of the old pre-nuragic world corresponding to a new historical turning point

— Giovanni Lilliu, La civiltà dei Sardi, p. 362, La civiltà nuragica pp. 25-27

The widespread diffusion of bronze brought numerous improvements. With the new alloy of copper and tin (or arsenic), a harder and more resistant metal was obtained, suitable for manufacturing tools used in agriculture, hunting and warfare. At a later phase of this period (Bonnanaro A2) probably dates the construction of the so-called proto-nuraghe,[23]: 37–71 a platformlike structure that marks the first phase of the Nuragic Age. These buildings are very different from the classical nuraghe having an irregular planimetry and a very stocky appearance. They are more numerous in the central-western part of Sardinia, later they spread in the whole Island.[32]

Middle and Late Bronze Age

[edit]

Dating to the middle of the 2nd millennium BC, the nuraghe, which evolved from the previous proto-nuraghe, are megalithic towers with a truncated cone shape; every Nuragic tower had at least an inner tholos chamber and the biggest towers could have up to three superimposed tholos chambers. They are widespread in the whole of Sardinia, about one nuraghe every three square kilometers.[31]: 9

Early Greek historians and geographers speculated about the mysterious nuraghe and their builders. They described the presence of fabulous edifices, called daidaleia, from the name of Daedalus, who, after building his labyrinth in Crete, would have moved to Sicily and then to Sardinia.[31]: 9 Modern theories about their use have included social, military, religious, or astronomical roles, as furnaces, or as tombs. Although the question has long been contentious among scholars, the modern consensus is that they were built as defensible homesites, and that included barns and silos.[33]

In the second half of the 2nd millennium BC, archaeological studies have proved the increasing size of the settlements built around some of these structures, which were often located at the summit of hills. Perhaps for protection reasons, new towers were added to the original ones, connected by walls provided with slits forming a complex nuraghe.[34]

Among the most famous of the numerous existing nuraghe, are the Su Nuraxi at Barumini, Santu Antine at Torralba, Nuraghe Losa at Abbasanta, Nuraghe Palmavera at Alghero, Nuraghe Genna Maria at Villanovaforru, Nuraghe Seruci at Gonnesa and Arrubiu at Orroli. The biggest nuraghe, such as Nuraghe Arrubiu, could reach a height of about 25–30 meters and could be made up of 5 main towers, protected by multiple layers of walls, for a total of dozens of additional towers.[35] It has been suggested that some of the current Sardinian villages trace their origin directly from Nuragic ones, including perhaps those containing the root Nur-/Nor- in their name like Nurachi, Nuraminis, Nurri, Nurallao, and Noragugume.[36]

Soon Sardinia, a land rich in mines, notably copper and lead, saw the construction of numerous furnaces for the production of alloys which were traded across the Mediterranean basin. Nuragic people became skilled metal workers; they were among the main metal producers in Europe,[37] and produced a wide variety of bronze objects. New weapons such as swords, daggers and axes preceded drills, pins, rings, bracelets, statuettes and the votive boats that show a close relationship with the sea. Tin may have drawn Bronze Age traders from the Aegean where copper is available but tin for bronze-making is scarce.[38] The first verifiable smelting slag has come to light, its appearance in a hoard of ancient tin confirms local smelting as well as casting.[39]

The usually cited tin sources and trade in ancient times are those in the Iberian Peninsula or from Cornwall. Markets included civilizations living in regions with poor metal resources, such as the Mycenaean civilization, Cyprus and Crete, as well as the Iberian peninsula, a fact that can explain the cultural similarities between them and the Nuraghe civilization and the presence in Nuragic sites of late Bronze Age Mycenaean, west and central Cretan and Cypriote ceramics, as well as locally made replicas, concentrated in half a dozen findspots that seem to have functioned as "gateway-communities".[40]

Sea Peoples connection

[edit]

The late Bronze Age (14th–13th–12th centuries BC) saw a vast migration of the so-called Sea Peoples, described in ancient Egyptian sources. They destroyed Mycenaean and Hittite sites and also attacked Egypt. According to Giovanni Ugas, the Sherden, one of the most important tribes of the sea peoples, are to be identified with the Nuragic Sardinians.[41][10][42] This identification has been also supported by Antonio Taramelli,[43] Vere Gordon Childe,[44] Sebastiano Tusa,[45][46] Vassos Karageorghis,[47] and Carlos Roberto Zorea, from the Complutense University of Madrid.[48]

Another hypothesis is that they came to the island around the 13th or 12th century after the failed invasion of Egypt; however, these theories remain controversial. Simonides of Ceos and Plutarch spoke of raids by Sardinians against the island of Crete, in the same period in which the Sea People invaded Egypt.[49][50] This would at least confirm that Nuragic Sardinians frequented the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Further proofs come from 13th-century Nuragic ceramics found at Tiryns, Kommos,[51] Kokkinokremnos,[52] Hala Sultan Tekke,[53] Minet el-Beida[54] and in Sicily, at Lipari,[55] and the Agrigento area, along the sea route linking western to eastern Mediterranean; ceramics similar to those of late Bronze Age Sardinia have also been found in the Egyptian port of Marsa Matruh.[56]

The archaeologist Adam Zertal has proposed that the Harosheth Haggoyim of Israel, home of the biblical figure Sisera, is identifiable with the site of "El-Ahwat" and that it was a Nuragic site suggesting that he came from the people of the Sherden of Sardinia.[57] Influences of the Nuragic architecture at El-Ahwat have been noticed also by Bar Shay, from Haifa University.[58]

Iron Age

[edit]Archaeologists traditionally define the nuragic phase ranging from 900 BC to 500 BC (Iron Age) as the era of the aristocracies. Fine ceramics were produced along with more and more elaborate tools and the quality of weapons increased. With the flourishing of trade, metallurgical products and other manufactured goods were exported to every corner of the Mediterranean, from the Near East to Spain and the Atlantic. The huts in the villages increased in number and there was generally a large increase in population. The construction of the nuraghes stopped, as many were abandoned or partially dismantled starting from 1150 BC,[59][60] and individual tombs replaced collective burials (Giant's Tombs).[61][62] According to archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu, the real breakthrough of that period was the political organization which revolved around the parliament of the village, composed by the heads and the most influential people, who gathered to discuss the most important issues.

Carthaginian and Roman conquest

[edit]

Around 900 BC the Phoenicians began visiting Sardinia with increasing frequency. The most common ports of call were Caralis, Nora, Bithia, Sulci, Tharros, Bosa and Olbia. The Roman historian Justin describes a Carthaginian expedition led by Malchus in 540 BC against a still strongly Nuragic Sardinia. The expedition failed and this caused a political revolution in Carthage, from which Mago emerged. He launched another expedition against the island, in 509 BC, after the Sardinians attacked the Phoenicians' coastal cities. According to Piero Bartoloni, it was Carthage that attacked the Phoenician cities in the coasts, rather than the natives who lived in those cities with the Phoenicians, for the Phoenician cities destroyed, such as Sulcis or Monte Sirai, he postulated as being inhabited mostly by native Sardinians.[63]

The Carthaginians, after a number of military campaigns in which Mago died and was replaced by his brother Hamilcar, overcame the Sardinians and conquered coastal Sardinia, the Iglesiente with its mines and the southern plains. The Nuragic culture may have survived in the mountainous interior of the island. In 238 BC, the Carthaginians, as a result of their defeat by the Romans in the first Punic War, surrendered Sardinia to Rome. Sardinia together with Corsica became a Roman province (Corsica et Sardinia), however the Greek geographer Strabo confirms the survival, in the interior of the island, of Nuragic culture at least into the early Imperial period.[64]

Society

[edit]

Religion had a strong role in Nuragic society, which has led scholars to the hypothesis that the Nuragic civilization was a theocracy. Some Nuraghe bronzes clearly portray the figures of chief-kings, recognizable by their wearing a cloak and carrying a staff with bosses. Also depicted are other classes, including miners, artisans, musicians, wrestlers (the latter similar to those of the Minoan civilizations) and many fighting men, which has led scholars to think of a warlike society, with precise military divisions (archers, infantrymen). Different uniforms could belong to different cantons or clans, or to different military units. The priestly role may have been fulfilled by women. Some small bronzes also give clues about Nuragic personal care and fashion. Women generally had long hair; men sported two long braids on each side of the face, while their head hair was cut very short or else covered by a leather cap.

Villages

[edit]

The Nuragic civilization was probably based on clans, each led by a chief, who resided in the complex nuraghe,[23]: 241 with common people living in the nearby villages of stone roundhouses with straw roofs, similar to the modern pinnettas of the Barbagia shepherds.

In the late final Bronze Age and in the Early Iron Age phases, the houses were built with a more complex plan, with multiple rooms often positioned around a courtyard; in the Nuragic settlement of Sant'Imbenia, located by the coast, some structures were not used for living purposes, but for the storing of precious metals, food and other goods and they were built around a huge square, interpreted by archaeologists as a marketplace.[65][66] The construction of rectangular houses and structures built with dried bricks is attested in some sites across the island since the late Bronze Age.[67]

Water management was essential for the Nuragic people, most complex Nuraghi were provided with at least a well; Nuraghe Arrubiu, for example, presented a complex hydraulic implant for the drainage of water[68] Another testimony to the Nuragic prowess in the creation of hydraulic implants is the aqueduct of Gremanu, the only known Nuragic aqueduct yet.[69]

During the final phase of the Bronze Age and the early Iron Age Sardinia saw the development of proto urban settlements, with open spaces such as paved squares and streets, and structures devoted to specific functions such as metal workshops, the individual houses were provided with storing facilities and were served by infrastructures.[70][71]

Tribes

[edit]

The most celebrated peoples of this island are the Ilienses, the Balari, and the Corsi ...

— Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Liber III

Throughout the second millennium and into the first part of the 1st millennium BC, Sardinia was inhabited by the single extensive and uniform cultural group represented by the Nuragic people. Centuries later, Roman sources describe the island as inhabited by numerous tribes which had gradually merged culturally. They however maintained their political identities and the tribes often fought each other for control of the most valuable land. The most important Nuragic populations mentioned include the Balares, the Corsi and the Ilienses, the latter defying the Romanization process and living in what had been called Civitatas Barbarie (now Barbagia).

- The Ilienses or Iolaes (later Diagesbes), identified by ancient writers as Greek colonists led by Iolaus (nephew of Heracles) or Trojan refugees, lived in what is now central-southern Sardinia. Greek historians reported also that they were repeatedly invaded by the Carthaginians and the Romans, but in vain.[72]

- The Balares have been identified with the Beaker culture.[23]: 22–32 They lived in what are now the Nurra, Coghinas and Limbara traditional subdivisions of Sardinia. They were probably of the same stock from which the Talaiotic culture of the Balearic Islands originated.[23]: 22–32

- The Corsi lived in Gallura and in Corsica. They have been identified as the descendants of the Arzachena culture. In southern Corsica, in the 2nd millennium BC, the Torrean civilization developed alongside the Nuragic one.

Culture

[edit]

Religion

[edit]The representations of animals, such as the bull, belong most likely to pre-Nuragic civilizations, however they kept their importance among the Nuraghe people, and were frequently depicted on ships, bronze vases, used in religious rites. Small bronze sculptures depicting half-man, half-bull figures have been found, as well as characters with four arms and eyes and two-headed deer: they probably had a mythological and religious significance. Another holy animal which was frequently depicted is the dove. Also having a religious role were perhaps the small chiseled discs, with geometrical patterns, known as pintadera, although their function has not been identified yet.

A key element of the Nuragic religion was that of fertility, connected to the male power of the Bull-Sun and the female one of Water-Moon. According to the scholars' studies, there existed a Mediterranean-type Mother Goddess and a God-Father (Babai). An important role was that of mythological heroes such as Norax, Sardus, Iolaos and Aristeus, military leaders also considered to be divinities.

The excavations have indicated that the Nuragic people, in determinate periods of the year, gathered in common holy places, usually characterized by sitting steps and the presence of a holy pit. In some holy areas, such as Gremanu at Fonni, Serra Orrios at Dorgali and S'Arcu 'e Is Forros at Villagrande Strisaili, there were rectangular temples, with central holy room housing perhaps a holy fire.[73] The deities worshipped are unknown but were perhaps connected to water, or to astronomical entities like Sun, Moon, and solstices.

Some structures could have a federal Sardinian role, such as the sanctuary of Santa Vittoria near Serri, which was one of the biggest Nuragic sanctuaries, spanning over 20 hectares,[74] including both religious and civil buildings.According to Italian historian Giovanni Lilliu, it was there that the main clans of the central island held their assemblies to sign alliances, decide wars, or to stipulate commercial agreements.[75] Spaces for trades were also present. At least twenty of such multirole structures are known, including those of Santa Cristina at Paulilatino and of Siligo; some have been re-used as Christian temples, such as the cumbessias of San Salvatore in Sinis at Cabras. Some ritual pools and bathtubs were built in the sanctuaries such as the pool of Nuraghe Nurdole, which worked through a system of raceways.[70] Furthermore, there are evidences of cults practiced in the caves in honor of a chthonic deity, as attested by the artefacts found in the Pirosu Cave of Santadi.

Holy wells

[edit]

The holy wells were structures dedicated to the cult of the water deity. Though initially assigned to the 8th–6th century BC, due to their advanced building techniques, they most likely date to the earlier Bronze Age, when Sardinia had strong relationships with the Mycenaean kingdoms of Greece and Crete, around the 14–13th century BC.[60]

The architecture of the Nuragic holy wells follows the same pattern as that of the nuraghe, the main part consisting of a circular room with a tholos vault with a hole at the summit. A monumental staircase connected the entrance to this subterranean (hypogeum) room, whose main role is to collect the water of the sacred spring. The exterior walls feature stone benches where offerings and religious objects were placed by the faithful. Some sites also had sacrificial altars. Some scholars think that these could be dedicated to Sardus, one of the main Nuragic divinities. A sacred pit similar to those of Sardinia has been found in western Bulgaria, near the village of Garlo.[76]

Roundhouses with basin

[edit]Starting from the late Bronze Age, a peculiar type of circular structure with a central basin and benches located all around the circumference of the room start to appear in Nuragic settlements, the best example of this type of structure is the ritual fountain of Sa Sedda e Sos Carros, near Oliena, where thanks to a hydraulic implant of lead pipes water was poured down from the ram shaped protomes inside the basin.[77] Some archaeologists interpreted these buildings, with ritual and religious function,[78] as thermal structures.[79]

Megaron temples

[edit]

Located in various parts of the Island and dedicated to the cult of the healthy waters, these unique buildings are an architectural manifestation that reflects the cultural vitality of the nuragic peoples and their interaction with the coeval mediterranean civilizations. In fact, many scholars see in these buildings foreign Aegean influences.[31]: 109

They have a rectilinear form with the side walls that extend outwardly. Some, like that of Malchittu at Arzachena, are apsidal while others such as the temple of Sa Carcaredda at Villagrande Strisaili culminate with a circular room. They are surrounded by sacred precincts called temenos. Sometimes multiple temples are found in the same location, such as in the case of the huge sanctuary of S'Arcu 'e Is Forros, where many megaron temples with a complex plant were excavated. The largest and best preserved Sardinian Mégara is that called Domu de Orgia at Esterzili.

Giant's graves

[edit]

The "giant's graves" were collective funerary structures whose precise function is still unknown, and which perhaps evolved from elongated dolmens. They date to the whole Nuragic era up to the Iron Age, when they were substituted by pit graves, and are more frequent in the central sector of the island. Their plan was in the shape of the head of a bull.

Large stone sculptures known as betili (a kind of slender menhir, sometimes featuring crude depiction of male sexual organs, or of female breasts) were erected near the entrance. Sometimes the tombs were built with an opus isodomum technique, where finely shaped stones were used, such as in the giant tombs of Madau or at Iloi.

Art

[edit]Bronze statuettes

[edit]

The bronzetti (brunzittos or brunzittus in Sardinian language) are small bronze statuettes obtained with the lost-wax casting technique; they can measure up to 39 cm (15 in) and represent scenes of everyday life, characters from different social classes, animal figures, divinities, ships etc. Most of them had been discovered in various sites of Sardinia; however, a sizeable minority had also been found in Etruscan sites, particularly tombs, of central Italy (Vulci, Vetulonia, Populonia, Magione) and Campania (Pontecagnano) and further south in the greek colony of Crotone.

Giants of Mont'e Prama

[edit]The Giants of Mont'e Prama are a group of 32 (or 40) statues with a height of up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft), found in 1974 near Cabras, in the province of Oristano. They depict warriors, archers, wrestlers, models of nuraghe and boxers with shield and armed glove. Depending on the different hypotheses, the dating of the Kolossoi – the name that archaeologist Giovanni Lilliu gave to the statues[80]: 84–86 – varies between the 11th and the 8th century BC.[81] If this is further confirmed by archaeologists, like the C-14 analysis already did, they would be the most ancient anthropomorphic sculptures of the Mediterranean area, after the Egyptian statues, preceding the kouroi of ancient Greece.[82]

They feature disc-shaped eyes and eastern-like garments. The statues probably depicted mythological heroes, guarding a sepulchre; according to another theory, they could be a sort of Pantheon of the typical Nuragic divinities. Their finding proved that the Nuragic civilization had maintained its peculiarities, and introduced new ones across the centuries, well into the Phoenician colonization of part of Sardinia.

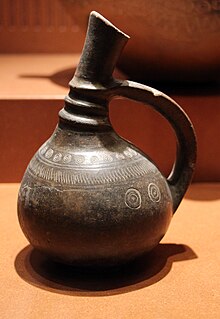

Ceramics

[edit]

In the ceramics, the skill and taste of the Sardinian artisans are manifested mainly in decorating the surfaces of vessels, certainly used for ritual purposes in the course of complex ceremonies, perhaps in some cases even to be crushed at the end of the rite, as the jugs found in the bottom of the sacred wells.[83] Ceramics also display geometric patterns on lamps, pear-shaped vessels (exclusive of Sardinia), and the askos. Imported (e.g. Mycenaeans) and local forms were found in several sites all over the island. Also found in the Italian peninsula, Sicily, in Spain and in Crete everything points to Sardinia being very well integrated in the ancient trade of the Mediterranean Sea.

Language

[edit]The language or languages spoken in Sardinia during the Bronze Age are unknown since there are no written records from the period, although recent research suggests that around the 8th century BC, in the Iron Age, the Nuragic populations may have adopted an alphabet of the "red" (western) type, similar to that used in Euboea.[20]

According to Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, the Paleo-Sardinian language was akin to Proto-Basque and ancient Iberian with faint Indo-European traces,[84] but others believe it was related to Etruscan. Giovanni Ugas theorize that there were actually various linguistic areas (two or more) in Nuragic Sardinia, possibly Pre-Indo-Europeans and Indo-Europeans.[23]: 241–254

Several scholars, including Johannes Hubschmid, Max Leopold Wagner and Emidio De Felice, distinguished different pre-Roman linguistic substrates in Sardinia. The oldest, pan-Mediterranean, widespread in the Iberian Peninsula, France, Italy, Sardinia and North Africa, a second Hispano-Caucasian substrate, which would explain the similarities between Basque and Paleo-Sardinian, and, finally, a Ligurian substrate.[85]

Economy

[edit]

The Nuragic economy, at least at the origins, was mostly based on agriculture (new studies suggest that they were the first to practice viticulture in the western Mediterranean[86]) and animal husbandry, as well as on fishing.[87] Alcoholic beverages like wine and beer were also produced, the cultivation of melons, probably imported from the Eastern Mediterranean, proves the practice of horticulture.[88] As in modern Sardinia, 60% of the soil was suitable only for breeding cattle and sheep. Probably, as in other human communities that have the cattle as traditional economic base, the property of this established social hierarchies. The existence of roads for wagons dating back to the 14th century BC gives the impression of a well organized society.[89] The signs found in the metal ingots testify the existence of a number system used for accounting among the Nuragic people.

Navigation had an important role: historian Pierluigi Montalbano mentions the finding of nuragic anchors along the coast, some weighing 100 kg (220 lb).[87] This has suggested that the Nuragic people used efficient ships, which could perhaps reach lengths up to 15 meters (49 ft). These allowed them to travel the whole Mediterranean, establishing commercial links with the Mycenaean civilization (attested by the common tholos tomb shape, and the adoration of bulls), Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Lebanon. Items such as Cyprus-type copper ingots have been found in Sardinia, while bronze and early Iron Age Nuragic ceramics have been found in the Aegean region, Cyprus,[90] in Spain (Huelva, Tarragona, Málaga, Teruel and Cádiz)[91] up to the Gibraltar strait, and in Etruscan centers of the Italian peninsula such as Vetulonia, Vulci and Populonia (known in the 9th to 6th centuries from Nuragic statues found in their tombs).

Sardinia was rich in metals such as lead and copper. Archaeological findings have proven the good quality of Nuragic metallurgy, including numerous bronze weapons. The so-called "golden age" of the Nuragic civilization (late 2nd millennium BC, early 1st millennium BCE) coincided perhaps with the apex of the mining of metals in the island. The widespread use of bronze, an alloy which used tin, a metal which however was not present in Sardinia except perhaps in a single deposit, further proves the capability of the Nuragic people to trade in the resources they needed. A 2013 study of 71 ancient Swedish bronze objects dated to Nordic Bronze Age, revealed that most of the copper utilized at that time in Scandinavia came from Sardinia and the Iberian peninsula.[92] Iron working is attested on the island since the 13th century BC.[93]

From the Late Bronze Age, amber, both from the Baltic and of unknown origin, appeared in Sardinia, coming via commercial traffic with continental Europe. Ambers, also worked locally, have been found both in residential contexts and in burials, sanctuaries and hoards.[94]

Paleogenetics

[edit]| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

A genetic study published in Nature Communications in February 2020 examined the remains of 17 individuals identified with Nuragic civilization. The samples of Y-DNA extracted belonged to haplogroup I2a1b1 (2 samples), R1b1b2a, G2a2b2b1a1, R1b1b (4 samples), J2b2a1 (3 samples) and G2a2b2b1a1a, while the samples of mtDNA extracted belonged to various types of haplogroup T, V, H, J, K and U.[95] The study found strong evidence of genetic continuity between Nuragic civilization and earlier Neolithic inhabitants of Sardinia, who were genetically similar to Neolithic peoples of Iberia and southern France.[96] They were determined to be of about 80% Early European Farmer (EEF) ancestry and 20% Western Hunter-Gatherer (WHG) ancestry.[97] They were predicted to be largely descended from peoples of the Neolithic Cardial Ware culture, which spread throughout the western Mediterranean in Southern Europe c. 5500 BC.[98] The Nuragic people were differentiated from many other Bronze Age peoples of Europe by the near absence of steppe-related ancestry.[96][99]

A 2021 study by Villalba-Mouco et al. has identified a possible gene flow originating from the Italian peninsula starting from the Chalcolithic. In prehistoric Sardinia, the component associated with Iranian farmers, or Caucasus-related ancestry, present in Mainland Italy since the Neolithic (together with the EEF and WHG components), gradually increases from 0% in the Early Chalcolithic to about 5.8% in the Bronze Age.[100] The absence of the component linked to the Magdalenians would instead exclude contributions from the Chalcolithic of the south of the Iberian peninsula.[100] According to a 2022 study by Manjusha Chintalapati et al., "In Sardinia, a majority of the Bronze Age samples do not have Steppe pastoralist-related ancestry. In a few individuals, we found evidence for steppe ancestry", which would arrive in ~2600 BC.[101] Below are the proportions of the ancestral components of a group of Nuragic individuals from Su Asedazzu (SUA), Seulo and S'Orcu 'e Tueri (ORC), Perdasdefogu.[101]

| Sample | Western-Hunter-Gatherer | Early European Farmers | Western Steppe Herders |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUA003 | 16,8% | 72,5% | 10,6% |

| SUA006 | 18,6% | 74,1% | 7,3% |

| ORC003 | 8,8% | 83,6% | 7,6% |

| ORC004 | 12,8% | 84,7% | 2,5% |

| ORC005 | 13,9% | 77,2% | 8,9% |

| ORC006 | 15,2% | 79,3% | 5,5% |

| ORC007 | 19,5% | 75,7% | 4,8% |

(1) - Data from Manjusha Chintalapati, Nick Patterson, Priya Moorjani (2022). Table J: qpAdm analysis of Neolithic Bronze Age groups per individual.

Genetic data appears to support the hypothesis of a patrilocal society.[102]

Physical appearance

[edit]The following results were obtained concerning eye pigmentation, as well as of hair follicles and skin, from the study on ancient DNA of 44 individuals who had lived during the Nuragic period, coming from central and north-western Sardinia. The eye color is blue in 16% of the examined samples and dark in the remaining 84%. Hair color is 9% blond or dark blond and 91% dark brown or black. The skin color is intermediate for 50%, intermediate or dark for 16%, and dark or very dark for the remaining 34%.[103]

In popular culture

[edit]Cinema and television

[edit]- Nuraghes S'Arena (2017) fantasy short film inspired by the Nuragic civilization featuring the Italian rapper Salmo.[104][105]

Opera

[edit]- I Shardana is an opera written by the Italian composer Ennio Porrino in 1959 set in Sardinia in the Nuragic period.

Music

[edit]- Atmospheric black metal project Downfall of Nur describes the collapse of Nuragic civilization in his albums.[106]

See also

[edit]| Ancient history |

|---|

| Preceded by prehistory |

|

Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The Nuragic Civilization in Sardinia (PDF), 2 November 2023

- ^ Paolo Melis (2003), The nuragic civilization, retrieved 2 November 2023

- ^ Webster, Gary S. 2015, pp. 12–39.

- ^ Leighton, Robert (2022). "Nuraghi as Ritual Monuments in the Sardinian Bronze and Iron Ages (circa 1700–700BC)". Open Archaeology. 8: 229–255. doi:10.1515/opar-2022-0224. hdl:20.500.11820/cdeed7fc-54f3-48f6-9ee4-c27eaa4b2a35. S2CID 248800046.

- ^ Cicilloni, Riccardo; Cabras, Marco (22 December 2014). "Aspetti insediativi nel versante oreintale del Monte Arci (Oristano -Sardegna) tra il bronzo medio e la prima età del ferro". Quaderni (in Italian) (25). Soprintendenza Archeologia, belle arti e paesaggio per la città metropolitana di Cagliari e le province di Oristano e Sud Sardegna: 84. ISSN 2284-0834.

- ^ a b Webster, Gary; Webster, Maud (1998). "The chronological and cultural definition of Nuragic VII, AD 456-1015". Sardinian and Aegean Chronology: 383–398. ISBN 1900188821. OCLC 860467990.

- ^ G. Lilliu (1999) p. 11[full citation needed]

- ^ Belmuth, Miriam S. (2012). "Nuragic Culture". In Fagan, Brian M. (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Vol. 1: ‘Ache’—‘Hoho’. Oxford University Press. p. 534. ISBN 9780195076189.

- ^ Martini, I. Peter; Chesworth, Ward (2010). Landscapes and Societies: Selected Cases. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 169. ISBN 9789048194131.

- ^ a b Ugas, Giovanni (2016). "Shardana e Sardegna. I popoli del mare, gli alleati del Nordafrica e la fine dei Grandi Regni". Cagliari, Edizioni Della Torre.

- ^ Rowland, R. J. “When Did the Nuragic Period in Sardinia End.” Sardinia Antiqua. Studi in Onore Di Piero Meloni in Occasione Del Suo Settantesimo Compleanno, 1992, 165–175.

- ^ Casula, Francesco Cèsare (2017). "Evo Antico Sardo: Dalla Sardegna Medio-Nuragica (100 a.C. c.) alla Sardegna Bizantina (900 d.C. c.)". La storia di Sardegna. Vol. I. p. 281.

Da parte imperiale era dunque implicito il riconoscimento di una Sardegna barbaricina indomita se non libera e già in qualche modo statualmente conformata, dove continuava a esistere una civiltà o almeno una cultura d'origine nuragica, certo mutata ed evoluta per influenze esterne romane e vandaliche di cui nulla conosciamo tranne alcuni tardi effetti politici.

- ^ Webster, Gary S.; Webster, Maud R. (1998). "The Duos Nuraghes Project in Sardinia: 1985-1996 Interim Report". Journal of Field Archaeology. 25 (2): 183–201. doi:10.2307/530578. ISSN 0093-4690. JSTOR 530578.

- ^ Nel BF numerosi indizi portano a supporre che i caratteri e l’assetto territoriale formatisi nel BM e BR, con l’edificazione dei nuraghi, subiscano mutamenti sostanziali che portano alla fine del fenomeno di costruzione di tali monumenti. Depalmas, Anna (2009). "Il Bronzo finale della Sardegna". Atti della XLIV Riunione Scientifica: La Preistoria e la Protostoria della Sardegna: Cagliari, Barumini, Sassari 23-28 Novembre 2009, Vol. 1: Relazioni Generali. 16 (4): 141–154.

- ^ No more new nuraghi were built after this period. Usai proposed that time and effort spent on their construction were no longer deemed proportional to their practical and symbolic use Gonzalez, Ralph Araque (2014). "Social Organization in Nuragic Sardinia: Cultural Progress Without 'Elites'?". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 1 (24): 141–161. doi:10.1017/S095977431400002X.

- ^ Giovanni Lilliu (2006). "Sardegna Nuragica" (PDF). Edizioni Maestrali. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2012.

- ^ Atzeni, E.; et al. (1985). Ichnussa. p. 5.[full citation needed]

- ^ "La civiltà Nuragica". Privincia del Sole (in Italian). 2007. Archived from the original on 29 May 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Monoja, M.; Cossu, C.; Migaleddu, M. (2012). Parole di segni, L'alba della scrittura in Sardegna. Sardegna Archeologica, Guide e Itinerari. Sassari: Carlo Delfino Editore.

- ^ a b Ugas, Giovanni (2013). "I segni numerali e di scrittura in Sardegna tra l'Età del Bronzo e il i Ferro". In Mastino, Attilio; Spanu, Pier Giorgio; Zucca, Raimondo (eds.). Tharros Felix. Vol. 5. Roma: Carocci. pp. 295–377.

- ^ Attilio Mastino (2004). "I miti classici e l'isola felice". In Raimondo Zucca (ed.). Le fonti classiche e la Sardegna. Atti del Convegno di Studi - Lanusei - 29 dicembre 1998 (in Italian). Vol. I. Roma: Carocci. p. 14. ISBN 88-430-3228-3.

- ^ Perra, M. (1993). La Sardegna nelle fonti classiche. Oristano: S'Alvure editrice.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ugas, Giovanni (2005). L'Alba dei Nuraghi. Cagliari: Fabula editrice. ISBN 978-88-89661-00-0.

- ^ Melis, Maria Grazia (2014). Meller, H.; Pernicka, E.; Risch, R. Risch (eds.). Silver in Neolithic and Eneolithic Sardinia. Metalle der Macht – Frühes Gold und Silber. 6. Mitteldeutscher Archäologentag vom 17. bis 19. Oktober 2013 in Halle. Halle: Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte Halle.

- ^ Luca Lai (2008). The Interplay of Economic, Climatic and Cultural Change Investigated Through Isotopic Analyses of Bone Tissue: The case of Sardinia 4000–1900 BC. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-549-77286-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Ercole Contu, Sardegna Archeologica – L'Altare preistorico di Monte D'Accoddi, p. 65

- ^ Giovanni Lilliu, Arte e religione della Sardegna prenuragica, p.132

- ^ "Alberto Moravetti, il complesso nuragico di Palmavera" (PDF). sardegnacultura.it. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Paolo Melis (January 2007), Una nuova sepoltura della cultura di Bonnanaro da Ittiri (Prov. di Sassari, Sardegna) ed i rapporti fra la Sardegna settentrionale e la Corsica nell'antica età del Bronzo (in Italian), retrieved 16 October 2023

- ^ Lilliu, Giovanni (2004). La civiltà dei Sardi dal paleolitico all'età dei nuraghi. Nuoro: Il Maestrale.

- ^ a b c d Lilliu, Giovanni (1982). La Civiltà Nuragica (PDF). Sassari: Delfino. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2012 – via Book on line from Sardegnadigiltallibrary.it.

- ^ Parkinson, E.W., McLaughlin, T.R., Esposito, C. et al. Radiocarbon Dated Trends and Central Mediterranean Prehistory. J World Prehist 34, 317–379 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10963-021-09158-4

- ^ The strict patterning in the landscape of tombs and nuraghes was analyzed by Blake, Emma (April 2001). "Constructing a Nuragic Locale: The Spatial Relationship between tombs and towers in Bronze Age Sardinia". American Journal of Archaeology. 105 (2): 145–161. doi:10.2307/507268. JSTOR 507268. S2CID 155610104.

- ^ Lilliu, Giovanni. "Sardegna Nuragica" (PDF). sardegnadigitallibrary.it. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Museo Nazionale Archeologico di Nuoro, Il Sarcidano: Orroli, Nuraghe Arrubiu Archived 2015-06-30 at the Wayback Machine(in Italian)

- ^ Francesco Cesare Casula, Breve storia di Sardegna, p. 25. ISBN 88-7138-065-7

- ^ "provinciadelsole.it". Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Tin as a draw for traders was first suggested in the essay on Sardinian metallurgy by N. Gale and Z. Gale in Miriam S. Balmuth, ed. Studies in Sardinian Archaeology 3 (Oxford, 1987).

- ^ R. F. Tylecote, M. S. Balmuth, R. Massoli-Novelli (1983). "Copper and Bronze Metallurgy in Sardinia". Historia Metallica. 17 (2): 63–77.

- ^ Miriam S. Balmuth, ed. Studies in Sardinian Archaeology 3: Nuragic Sardinia and the Mycenaean World (Oxford, 1987) presents papers from a colloquium in Rome, September 1986; the view of "gateway-communities" from the Mycenaean direction is explored in T.R. Smith, Mycenaean Trade and Interaction in the West Central Mediterranean, 1600–100 B.C., 1987.

- ^ "Giovanni Ugas: Shardana". Sp Intervista. Archived from the original on 5 April 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ "Nuovo studio dell'archeologo Ugas". 3 February 2017.

È certo, i nuragici erano gli Shardana.

- ^ Taramelli, Antonio (1982). Scavi e scoperte. 1903-1910 (in Italian). Sassari: Carlo Delfino editore. OCLC 643856632.

Ma io ritengo che le conseguenze della nostra osservazione sulla continuità degli elementi eneolitici in quelli della civiltà nuragica abbiano una portata maggiore di quella veduta dal collega mio; che cioè la civiltà degli Shardana siasi qui elaborata completamente, dai suoi germi iniziali, sia qui cresciuta, battagliera, vigorosa, e che lungi dal vedere nella Sardegna l'estremo rifugio di una razza dispersa, inseguita, come una fiera fuggente, dall'elemento semitico che venne qui ad azzannarla e a soggiogarla, noi dobbiamo vedere il nido donde essa spiegò un volo ardito, dopo aver lasciato una impronta di dominio, di lotta, di tenacia, sul suolo da lei guadagnato alla civiltà.

- ^ Gordon Childe, Vere (1930). The Bronze Age.

In the nuragic sanctuaries and hoards we find an extraordinary variety of votive statuettes and models in bronze. Figures of warriors, crude and barbaric in execution but full of life, are particularly common. The warrior was armed with a dagger and bow-and-arrows or a sword, covered with a two-horned helmet and protected by a circular buckler. The dress and armament leave no doubt as to the substantial identity of the Sardinian infantryman with the raiders and mercenaries depicted on Egyptian monuments as "Shardana". At the same time numerous votive barques, also of bronze, demonstrate the importance of the sea in Sardinian life.

- ^ Tusa, Sebastiano (2018). I popoli del Grande Verde: il Mediterraneo al tempo dei faraoni (in Italian). Ragusa: Edizioni Storia e Studi Sociali. ISBN 9788899168308. OCLC 1038750254.

- ^ Presentazione del libro "I Popoli del Grande Verde" di Sebastiano Tusa presso il Museo del Vicino Oriente, Egitto e Mediterraneo della Sapienza di Roma (in Italian). 21 March 2018. Event occurs at 12:12.

- ^ Karageorghis, Vassos (2011). "Handmade Burnished Ware in Cyprus and elsewhere in the Mediterranean". On cooking pots, drinking cups, loomweights and ethnicity in bronze age Cyprus and neighbouring regions: an international archaeological symposium held in Nicosia, November 6th-7th, 2010. A.G. Leventis Foundation. p. 90. ISBN 978-9963-560-93-6. OCLC 769643982.

It is most probable that among the Aegean immigrants there were also some refugees from Sardinia. This may corroborate the evidence from Medinet Habu that among the Sea Peoples there were also refugees from various part of the Mediterranean, some from Sardinia, the Shardana or Sherden. [...] It is probable that these Shardana went first to Crete and from there they joined a group of Cretans for an eastward adventure.

- ^ Zorea, Carlos Roberto (2021). Sea peoples in Canaan, Cyprus and Iberia (12th to 10th centuries BC) (PDF). Madrid: Complutense University of Madrid.

- ^ Pallottino 2000, p. 119.

- ^ "Paola Ruggeri - Talos, l'automa bronzeo contro i Sardi: le relazioni più antiche tra Creta e la Sardegna" (PDF). uniss.it. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Ceramiche. Storia, linguaggio, e prospettive in Sardegna" (PDF). p. 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- ^ Gale, N.H. (2011). "Source of the Lead Metal used to make a Repair Clamp on a Nuragic Vase recently excavated at Pyla-Kokkinokremos on Cyprus". In V. Karageorghis; O. Kouka (eds.). On Cooking Pots, Drinking Cups, Loomweights and Ethnicity in Bronze Age Cyprus and Neighbouring Regions. Nicosia.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gradoli, Maria G.; Waiman-Barak, Paula; Bürge, Teresa; Dunseth, Zachary C.; Sterba, Johannes H.; Schiavo, Fulvia Lo; Perra, Mauro; Sabatini, Serena; Fischer, Peter M. (2020). "Cyprus and Sardinia in the Late Bronze Age: Nuragic table ware at Hala Sultan Tekke". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 33: 102479. Bibcode:2020JArSR..33j2479G. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102479. S2CID 224982889.

- ^ Jung, Reinhard; Kostopoulou, Ioanna (January 2023), "Observations on the Pottery of the 2014-2019 Campaigns", J. Bretschneider/A. Kanta/J. Driessen, Excavations at Pyla-Kokkinokremos. Report on the 2014–2019 Campaigns. Aegis 24, retrieved 10 October 2023

- ^ Santoni, Vincenzo; Sabatini, Donatella (2010). "Relazione e analisi preliminare". Campagna di scavo (PDF) (Report). Gonnesa, Nuraghe Serucci. Vol. IX.

- ^ Cultraro, Massimo, Un mare infestato da mercanti e pirati:relazioni e rotte commerciali tra Egitto e Sicilia nel II millennio a.C. (in Italian), retrieved 16 October 2023

- ^ Siegel-Itzkovich, Judy (2 July 2010). "Long time archaeological riddle solved: Canaanite general was based in Wadi Ara". Jerusalem Post.

- ^ "Archaeological site could cast light on life of Biblical Villain Sisera". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 27 November 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

When you look at plans of sites of the Shardana in Sardinia, in the second millennium BCE, throughout this entire period, you can see wavy walls, you can see corridors... you can see high heaps of stones, which were developed into the classical nuraghic culture of Sardinia. The only good architectural parallels are found in Sardinia and the Shardana culture.

- ^ Bernardini, Paolo (2012). Necropoli della Prima Età del Ferroin Sardegna. Una riflessione su alcuni secoli perdutio, meglio, perduti di vista. I Nuragici, i Fenici e gli Altri. Sardegna e Mediterraneo tra Bronzo Finale e Prima Età del Ferro. Atti del I Congresso Internazionale in occasione del Venticinquennale del Museo Genna Maria di Villanovaforru, Villanovaforru 14-15 dicembre 2007. pp. 135–149. Retrieved 24 April 2024 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ a b Campus, Franco; Leonelli, Valentina; Lo Schiavo, Fulvia. "La transizione culturale dall'età del bronzo all'età del ferro nella Sardegna nuragicain relazione con l'Italia tirrenica" (PDF). beniculturali.it. Bollettin o di Archeologia Online (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- ^ Tronchetti, Carlo (2012). Quali aristocrazie nella Sardegna dell'età del Ferro?. Atti della XLIV Riunione Scientifica: La Preistoria e la Protostoria della Sardegna. Firenze: Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria. pp. 851–856. Retrieved 3 May 2015 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ Bernardini, Paolo (2011). Necropoli della Prima Età del Ferro in Sardegna: una riflessione su alcuni secoli perduti o, meglio, perduti di vista. Carocci. pp. 351–386. ISBN 978-88-430-5751-1. Retrieved 24 April 2024 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Bartoloni, Piero (2004). Monte Sirai (PDF). Sardegna Archeologica, Guide e Itinerari. Vol. 10 (Nuova ed.). Sassari: Carlo Delfino editore. ISBN 88-7138-172-6.

- ^ Strabo. Geographica (in Ancient Greek). Vol. 3, XVII.

- ^ Rendeli, Marco. "Il Progetto Sant'Imbenia". academia.edu. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ De Rosa, Beatrice Alba Lidia. "Sant'Imbenia (Alghero, SS). Il contributo dell'archeometria nella ricostruzione della storia e delle attività dell'abitato nuragico" (PDF) (in Italian).

- ^ Mossa, Alberto (8 June 2017). "San Sperate (Ca-Sardegna), Via Monastir. Le ceramiche nuragiche del Bronzo recente II e finale: caratteristiche formali ed aspetti funzionali". Layers: Archeologia Territorio Contesti (2). doi:10.13125/2532-0289/2668.

- ^ Lo Schiavo, Fulvia; Sanges, M. "Il Nuraghe Arrubiu di Orroli".

- ^ Fadda, Maria Ausilia. "Gli architetti nuragici di Gremanu".

- ^ a b "Sardegna Digital Library" (PDF). 20161222154027.

- ^ Rendeli, Marco (2017). Moravetti, A.; Melis, P.; Foddai, L.; Alba, E. (eds.). "La Sardegna nuragica Storia e Monumenti". Sassari: Carlo Delfino Editore.

- ^ Pausanias. Hellados Periegesis [Description of Greece]. IX, 17, 5.

- ^ Lilliu, Giovanni. "Arte e religione della Sardegna nuragica" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2012.

- ^ Mancini, Paola (2011). "Il santuario di Santa Vittoria di Serri" (PDF). Campagna di scavo (in Italian).

- ^ Lilliu, Giovanni (1967). "Al tempo dei nuraghi". La civiltà in Sardegna nei secoli. Turin: ERI. p. 22.

- ^ Mitova-Dzonova, D. (1983). Megalithischer Brunnentempel protosardinischen Typs vom Dorf Garlo, Bez. Pernik. Sofia: Komitee fur Kultur.

- ^ Salis, Gianfranco. "Sa Sedda e Sos Carros di Oliena" (in Italian).

- ^ "Complesso nuragico Sa Seddà e Sos Carros" (in Italian). Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ Paglietti, Giacomo (January 2009). "Le rotonde con bacile di età nuragica". Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche (in Italian).

- ^ Lilliu, Giovanni (2006). Sardegna Nuragica (PDF). Nuoro: Edizioni Il Maestrale. ISBN 978-88-89801-11-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2012 – via Book on line from Sardegnadigitallibrary.it.

- ^ Andreoli, Alice (27 July 2007). "L'armata sarda dei Giganti di pietra". Il Venerdì di Repubblica. Rome: Gruppo Editoriale L'Espresso. pp. 82–83.

- ^ Leonelli, Valentina (2012). "Restauri Mont'e Prama, il mistero dei giganti". Archeo. Attualità del Passato (in Italian): 26–28. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- ^ AA. VV., Le sculture di Mont'e Prama - Contesto, scavi e materiali, p.51[full citation needed]

- ^ Ferrer, Eduardo Blasco, ed. (2010). Paleosardo: Le radici linguistiche della Sardegna neolitica [Paleosardo: The Linguistic Roots of Neolithic Sardinian]. De Gruyter Mouton.

- ^ Iribarren Argaiz, Mary Carmen (1997). "Los vocablos en -rr- de la lengua sarda.Conexiones con la península ibérica". Fontes Linguae Vasconum: Studia et Documenta (in Spanish). 29 (76): 335–354. doi:10.35462/flv76.2. Retrieved 3 December 2002.

- ^ "E' in Sardegna il più antico vitigno del Mediterraneo occidentale". www.unica.it. Università degli studi di Cagliari. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ a b Montalbano, Pierluigi (July 2009). SHRDN, Signori del mare e del metallo. Nuoro: Zenia. ISBN 978-88-904157-1-5.

- ^ "L'insediamento Nuragico di sa osa cabras or, il sito e i materiali".

- ^ Manunza, Maria Rosaria (21 December 2016). "Manufatti nuragici e micenei lungo una strada dell'età del bronzo presso Bia 'e Palma - Selargius (CA)". Quaderni (27): 147–200.

- ^ "Revisiting Late Bronze Age oxhide ingots – Meanings questions and perspectives".

- ^ Fundoni, Giovanna (January 2012). "Le ceramiche nuragiche nella Penisola Iberica e le relazioni tra la Sardegna e la Penisola Iberica nei primi secoli del I millennio a.c." Atti della Xliv Riunione Scientifica "la Preistoria e la Protostoria della Sardegna". Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Ling, Johan; Stos-Gale, Zofia; Grandin, Lena; Billström, Kjell; Hjärthner-Holdar, Eva; Persson, Per-Olof (2014). "Moving metals II: Provenancing Scandinavian Bronze Age artefacts by lead isotope and elemental analyses". Journal of Archaeological Science. 41: 106–132. Bibcode:2014JArSc..41..106L. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.07.018.

- ^ Mossa, Alberto (21 December 2016). "La siderurgia quale indicatore di contatti tra la Sardegna e Cipro: il caso del settore nuragico di Via Monastir di San Sperate (CA)". Quaderni (27): 107–124. Retrieved 8 April 2018 – via www.quaderniarcheocaor.beniculturali.it.

- ^ Usai, Alessandro, Ambre protostoriche della Sardegna: nuovi dati su tipologia e possibili indicatori di lavorazione locale, retrieved 8 September 2024

- ^ Marcus et al. 2020, Supplementary Data 1, A Master Table.

- ^ a b Marcus et al. 2020, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Marcus et al. 2020, p. 3.

- ^ Marcus et al. 2020, pp. 2, 9.

- ^ Clemente, Florian; Unterländer, Martina; Dolgova, Olga; Amorim, Carlos Eduardo G.; Coroado-Santos, Francisco; Neuenschwander, Samuel; Ganiatsou, Elissavet; Cruz Dávalos, Diana I.; Anchieri, Lucas; Michaud, Frédéric; Winkelbach, Laura (13 May 2021). "The genomic history of the Aegean palatial civilizations". Cell. 184 (10): 2565–2586.e21. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.039. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 8127963. PMID 33930288.

- ^ a b Villalba-Mouco, Vanessa; et al. (2021). "Genomic transformation and social organization during the Copper Age–Bronze Age transition in southern Iberia". Science Advances. 7 (47): eabi7038. Bibcode:2021SciA....7.7038V. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abi7038. hdl:10810/54399. PMC 8597998. PMID 34788096.

- ^ a b Manjusha Chintalapati, Nick Patterson, Priya Moorjani (2022) The spatiotemporal patterns of major human admixture events during the European Holocene eLife 11:e77625 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.77625

- ^ Lai, Luca; Crispu, Stefano (2024), "Social Organization, Intersections, and Interactions in Bronze Age Sardinia. Reading Settlement Patterns in the Area of Sarrala with the Contribution of Applied Sciences", Open Archaeology, 10, doi:10.1515/opar-2022-0358, retrieved 1 September 2024

- ^ Tina Saupe et al.,Ancient genomes reveal structural shifts after the arrival of Steppe-related ancestry in the Italian Peninsula, Supplemental information, Data S6. Main results of phenotype prediction, related to Table 3 and STAR Methods. (A) Description of the groups used for the phenotype prediction and related analyses. (B) Frequency of the effective allele in Italian, Near Eastern, and Yamnaya groups and ANOVA results. (C) Frequency of the effective allele in different Italian groups and ANOVA results. (D) Sample-by-sample phenotype prediction and genotype at the selected phenotype informative markers (reported as number of effective alleles: 0, 1, or 2), 2021.

- ^ "Nuraghes S'arena". IMDb. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ il Giornale, ed. (15 March 2017). "L'antica civiltà del Nuraghe in un fantasy Il protagonista è il rapper Salmo". Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Antonio Sanna from Downfall of Nur". Echoes And Dust. 13 November 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Atzeni, Enrico (1981). Ichnussa. La Sardegna dalle origini all'età classica. Milan.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Bernardini, Paolo (2010). Le torri, i metalli, il mare. Sassari: Carlo Delfino Editore.

- Depalmas, Anna (2005). Le navicelle di bronzo della Sardegna nuragica. Cagliari: Gasperini.

- Dyson, Stephen L.; Rowland, Robert J. (2007). Shepherds, sailors, & conquerors - Archeology and History in Sardinia from the Stone Age to the Middle Ages. Museum of Archeology and Anthropology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. ISBN 978-1-934536-02-5.

- Foddai, Lavinia (2008). Sculture zoomorfe. Studi sulla bronzistica figurata nuragica. Cargeghe: Biblioteca di Sardegna.

- Laner, Franco (2011). Sardegna preistorica, dagli antropomorfi ai telamoni di Monte Prama, Sa 'ENA. Cagliari: Condaghes.

- Lilliu, Giovanni (1966). Sculture della Sardegna nuragica (PDF). Cagliari: La Zattera. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2013 – via Book online from Sardegnadigitallibrary.it ed. 2008 Illisso.

- Lilliu, Giovanni (1967). La civiltà in Sardegna nei secoli. Turin: ERI.

- Marcus, Joseph H.; et al. (24 February 2020). "Genetic history from the Middle Neolithic to present on the Mediterranean island of Sardinia". Nature Communications. 11 (939). Nature Research: 939. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11..939M. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-14523-6. PMC 7039977. PMID 32094358.

- Melis, Paolo (2003). Civiltà nuragica. Sassari: Delfino Editore.

- Montalbano, Pierluigi (July 2009). SHRDN, Signori del mare e del metallo. Nuoro: Zenia Editrice. ISBN 978-88-904157-1-5.

- Navarro i Barba, Gustau (2010). La Cultura Nuràgica de Sardenya. Barcelona: Edicions dels A.L.I.LL. ISBN 978-84-613-9278-0.

- Pallottino, Massimo (2000). La Sardegna nuragica. Nuoro: edizioni Ilisso. ISBN 978-88-87825-10-7.

- Perra, Mario (1997). ΣΑΡΔΩ, Sardinia, Sardegna. Oristano: S'Alvure.

3 Volumes

- Pittau, Massimo (2001). La lingua sardiana o dei protosardi. Cagliari: Ettore Gasperini editore.

- Pittau, Massimo (2007). Storia dei sardi nuragici. Selargius: Domus de Janas editrice.

- Pittau, Massimo (2008). Il Sardus Pater e i Guerrieri di Monte Prama. Sassari: EDES.

- Pittau, Massimo (2011). Gli antichi sardi fra I "Popoli del mare". Selargius: Domus de Janas editrice.

- Pittau, Massimo (2013). La Sardegna nuragica. Cagliari: Edizioni della Torre.

- Scintu, Danilo (2003). Le Torri del cielo, Architettura e simbolismo dei nuraghi di Sardegna. Mogoro: PTM editrice.

- Vacca, E.B. (1994). La civiltà nuragica e il mare. Quartu Sant'Elena: ASRA editrice.

- Webster, Gary S. (1996). A Prehistory of Sardinia 2300-500 BCE. Monographs in Mediterranean Archaeology. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 978-1850755081.

- Webster, Gary S. (2015). The Archaeology of Nuragic Sardinia. Bristol, CT: Equinox Publishing Ltd.

Further reading

[edit]- Balmuth, Miriam S. (1987). Nuragic Sardinia and the Mycenaean World. Oxford, England: B.A.R.

- Zedda, Mauro Peppino (2016). "Orientation of the Sardinian Nuragic 'meeting huts'". Mediterranean Archaeology & Archaeometry. 16 (4): 195–201.