Carnotaurini

It has been suggested that this article be merged into Carnotaurinae. (Discuss) Proposed since April 2024. |

| Carnotaurini Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted cast of a Carnotaurus sastrei skeleton, Chlupáč Museum, Prague | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Abelisauridae |

| Clade: | †Furileusauria |

| Tribe: | †Carnotaurini Coria et al. 2002 |

| Type species | |

| †Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte, 1985

| |

| Genera | |

| |

Carnotaurini is a tribe of the theropod dinosaur family Abelisauridae from the Late Cretaceous period of Patagonia. It includes the dinosaurs Carnotaurus sastrei; the type species, Aucasaurus garridoi, and Abelisaurus comahuensis. This group was first proposed by paleontologists Rodolfo Coria, Luis Chiappe, and Lowell Dingus in 2002, being defined as a clade containing "Carnotaurus sastrei, Aucasaurus garridoi, their most recent common ancestor, and all of its descendants."

Description[edit]

Anatomical description and geological distribution[edit]

Carnotaurins were relatively lightly built but large theropods, ranging in size from 6.1–7.8 m (20–26 ft)[1] and 1400–2000 kg (1.6–2.3 short tons) in weight.[2][3] They were located in South America. All three species have been found in various[That's two, which is not enough for "various".] formations in Argentina: the Anacleto Formation of the Rio Colorado Subgroup in the Neuquén Basin and possibly the Sir Fernandez field of the Allen Formation to the southeast.[4][5][6] They are considered the most derived abelisaurids, with traits like very short, narrow skulls and extremely reduced forearms, even more so than other abelisaurids.[5][7]

Paleobiology[edit]

Studies of the skull anatomy of the nominal species, Carnotaurus sastrei, lead to debate over what type of prey these animals hunted. Studies by Mazzetta et al. in 1998, 2004, and 2009 suggest that the jaw structure in Carnotaurus was built for swift, rather than strong, bites, with adaptations for mandibular kinesis to assist in swallowing small prey items whole.[8] Surprisingly, it exhibits a form of paracraniokinesis in which the dentary bone articulates against the surangular bone, further jointing the lower jaw and hypothetically allowing this animal a wider array of hunting strategies.[9]

However, in 1998 and 2009, Robert Bakker and Francois Therrien and colleagues contested this finding, stating that Carnotaurus had the exact same skull adaptations (short snout, small teeth, and a fortified occiput) as the Jurassic theropod Allosaurus, which presumably preyed upon large animals by gradual jaw slashing.[10]

Locomotion[edit]

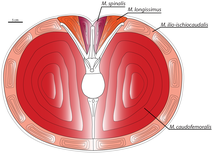

Mazzetta et al. 1998–1999 and Phil Currie et al. 2011 found Carnotaurus to be a swift-running predator with semicursorial adaptations such as femoral resistance against bending moments[11] and a hypertrophied caudofemoralis muscle, the primary locomotory muscle in theropods which was located in the tail and pulled the femur backwards.[12] This enlarged caudofemoralis, giving them a speed estimate of 48–56 km/h (30–35 mph), allowed carnotaurins to be one of the fastest-running large theropod groups yet known.[13][12]

Systematics[edit]

Past[edit]

The tribe Carnotaurini was named in 2002 by Rodolfo Coria et al. in 2002 after their discovery of Aucasaurus garridoi. They phylogenetically defined it as the most inclusive clade containing Carnotaurus sastrei, Aucasaurus garridoi, their most recent common ancestor, and all of its descendants.[14] Their morphological definition of it is by several synapomorphies of the clade, with two ambiguous ones: "the presence of hyposphene–hypantrum articulations in the proximal and middle sections of the caudal series, and cranial processes in the epipophyses of the cervical vertebrae." They defined more ambiguous synapomorphies due to the homologous materials not yet found in all other abelisaurids being: "a very broad coracoid (coracoid maximum width three times the distance across the scapular glenoid area), a humerus with a large and hemispherical head, an extremely short ulna and radius (ulna to humerus ratio 1:3 or less), and frontal prominences (swells or horns) that are located laterally on the skull roof."[15] The relatively outdated cladogram that they found is as follows:

Later in 2009, the carnotaurine Skorpiovenator was described by Juan Canale, Carlos Scanferla, Federico Agnolin, and Fernando E. Novas, who performed another phylogenetic study supporting the monophyly of Carnotaurini:[16]

Present[edit]

According to the modern consensus, as of the cladogram published in the description of Tralkasaurus cuyi after Cerroni et al. 2020, the tribe also contains Abelisaurus comahuensis, which has been found to be the closest relative of Aucasaurus garridoi and has been united with it under the clade Abelisaurinae across multiple occasions.[17][18]

References[edit]

- ^ Grillo, O. N.; Delcourt, R. (2016). "Allometry and body length of abelisauroid theropods: Pycnonemosaurus nevesi is the new king". Cretaceous Research. 69: 71–89. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.09.001.

- ^ Grillo, O. N.; Delcourt, R. (2016). "Allometry and body length of abelisauroid theropods: Pycnonemosaurus nevesi is the new king". Cretaceous Research. 69: 71–89. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.09.001.

- ^ Mazzetta *, Gerardo V.; Christiansen †, Per; Fariña, Richard A. (June 2004). "Giants and Bizarres: Body Size of Some Southern South American Cretaceous Dinosaurs". Historical Biology. 16 (2–4): 71–83. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.1650. doi:10.1080/08912960410001715132. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 56028251.

- ^ Bonaparte, J.; Novas, E.E. (1985). "Abelisaurus comahuensis, n.g., n.sp., Carnosauria del Crétacico Tardio de Patagonia" [Abelisaurus comahuensis, n.g., n.sp., Carnosauria from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia]. Ameghiniana. 21: 259–265 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ a b Bonaparte, José F.; Novas, Fernando E.; Coria, Rodolfo A. (1990). "Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte, the horned, lightly built carnosaur from the Middle Cretaceous of Patagonia" (PDF). Contributions in Science. 416: 1–41. doi:10.5962/p.226819. S2CID 132580445. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2010.

- ^ Benton, Michael J. (2012). Prehistoric Life. Edinburgh, Scotland: Dorling Kindersley. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-7566-9910-9.

- ^ Coria, Rodolfo A.; Chiappe, Luis M.; Dingus, Lowell. "A NEW CLOSE RELATIVE OF CARNOTAURUS SASTREI BONAPARTE 1985(THEROPODA: ABELISAURIDAE) FROM THE LATE CRETACEOUS OF PATAGONIA". researchgate.net. Retrieved 2 November 2002.

- ^ Mazzetta, Gerardo V.; Cisilino, Adrián P.; Blanco, R. Ernesto; Calvo, Néstor (2009). "Cranial mechanics and functional interpretation of the horned carnivorous dinosaur Carnotaurus sastrei". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (3): 822–830. doi:10.1671/039.029.0313. hdl:11336/34937. S2CID 84565615.

- ^ Mazzetta, Gerardo V.; Fariña, Richard A.; Vizcaíno, Sergio F. (1998). "On the palaeobiology of the South American horned theropod Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte" (PDF). Gaia. 15: 185–192.

- ^ Bakker, Robert T. (1998). "Brontosaur killers: Late Jurassic allosaurids as sabre-tooth cat analogues" (PDF). Gaia. 15: 145–158.

- ^ Mazzetta, Gerardo V.; Farina, Richard A. (1999). "Estimacion de la capacidad atlética de Amargasaurus cazaui Salgado y Bonaparte, 1991, y Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte, 1985 (Saurischia, Sauropoda-Theropoda)". XIV Jornadas Argentinas de Paleontologia de Vertebrados, Ameghiniana (in Spanish). 36 (1): 105–106.

- ^ a b Persons, W.S.; Currie, P.J. (2011). Farke, Andrew Allen (ed.). "Dinosaur Speed Demon: The caudal musculature of Carnotaurus sastrei and implications for the evolution of South American abelisaurids". PLOS ONE. 6 (10): e25763. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...625763P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025763. PMC 3197156. PMID 22043292.

- ^ "Predatory dinosaur was fearsomely fast". CBC News. October 21, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2017.

- ^ Coria, Rodolfo A.; Chiappe, Luis M.; Dingus, Lowell. "A NEW CLOSE RELATIVE OF CARNOTAURUS SASTREI BONAPARTE 1985 (THEROPODA: ABELISAURIDAE) FROM THE LATE CRETACEOUS OF PATAGONIA". researchgate.net. Retrieved 2 November 2002.

- ^ Coria, Rodolfo A.; Chiappe, Luis M.; Dingus, Lowell. "A NEW CLOSE RELATIVE OF CARNOTAURUS SASTREI BONAPARTE 1985(THEROPODA: ABELISAURIDAE) FROM THE LATE CRETACEOUS OF PATAGONIA". researchgate.net. Retrieved 2 November 2002.

- ^ Canale, J. I.; Scanferla, C. A.; Agnolin, F. L.; Novas, F. E. (2008). "New carnivorous dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of NW Patagonia and the evolution of abelisaurid theropods" (PDF). Naturwissenschaften. 96 (3): 409–414. Bibcode:2009NW.....96..409C. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0487-4. hdl:11336/52024. PMID 19057888. S2CID 23619863.

- ^ Coria, Rodolfo A.; Chiappe, Luis M.; Dingus, Lowell (2002). "A new close relative of Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte 1985 (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (2): 460–465. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0460:ANCROC]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 131148538 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Cerroni, M.A.; Motta, M.J.; Agnolín, F.L.; Aranciaga Rolando, A.M.; Brissón Egli, F.; Novas, F.E. (2020). "A new abelisaurid from the Huincul Formation (Cenomanian-Turonian; Upper Cretaceous) of Río Negro province, Argentina". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 98: 102445. Bibcode:2020JSAES..9802445C. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2019.102445. S2CID 213781725.