Black-owned business

African-American businesses, also known as black owned businesses or black businesses, can be traced back to when Africans were first forcibly brought to North American in the 17th century. Many African Americans who gained their own freedom out of slavery opened their own businesses, and even some enslaved African Americans were able to operate their own businesses, either as skill tradespeople or as minor traders and peddlers. Enslaved African Americans operated businesses both with and without their owners' permission.

Emancipation and civil rights permitted businessmen to operate inside the American legal structure starting in the Reconstruction Era (1863–77) and afterwards. By the 1890s, thousands of small business operations had opened in urban areas. The most rapid growth came in the early 20th century, As the increasingly rigid Jim Crow system of segregation moved urban blacks into a community large enough to support a business establishment. The National Negro Business League, Promoted by college president Booker T. Washington the League opened over 600 chapters, reaching every city with a significant black population.

By 1920, there were tens of thousands of black businesses, the great majority of them quite small. The largest were insurance companies. The League had grown so large that it supported numerous offshoots, including the National Negro Bankers Association, the National Negro Press Association, the National Association of Negro Funeral Directors, the National Negro Bar Association, the National Association of Negro Insurance Men, the National Negro Retail Merchants' Association, the National Association of Negro Real Estate Dealers, and the National Negro Finance Corporation.[1] The Great Depression of 1929-39 was a serious blow, as cash income fell in the black community because of unemployment, and many smaller businesses close down. During World War II many employees can indeed owners switched over to high-paying jobs in munitions factories. Black businessmen generally were more conservative elements of their community, but typically did support the civil rights movement. By the 1970s, federal programs to promote minority business activity provided new funding, although the opening world of mainstream management attracted a great deal of talent.

To 1865

Free blacks Facing a generally hostile environment occasionally operated small businesses.[2]

1865-1900

The South had relatively few cities of any size in 1860, But during the war, and afterward, refugees both black and white flooded in from rural areas. The growing black population produced a leadership class of ministers, professionals, and businessmen.[3][4] These leaders typically made civil rights a high priority. Of course, great majority of blacks in urban America were unskilled or low skilled blue-collar workers.Historian August Meier reports:

- From the late 1880s there was a remarkable development of Negro business – banks and insurance companies, undertakers and retail stores.... It occurred at a time when Negro barbers, tailors caterers, trainmen, blacksmiths, and other artisans were losing their way customers. Depending upon the Negro market, the promoters of the new enterprises naturally upheld the spirit of racial self-help and solidarity.[5][6]

Memphis Tennessee was the base for Robert Reed Church (1839-1912), a freedman who became the South's first black millionaire.[7] He made his wealth from speculation in city real estate, much of it after Memphis became depopulated after the yellow fever epidemics. He founded the city's first black-owned bank, Solvent Savings Bank, ensuring that the black community could get loans to establish businesses. He was deeply involved in local and national Republican politics and directed patronage to the black community. His son Robert Reed Church, Jr., became a major politician in Memphis. He was a leader of black society and a benefactor in numerous causes.

The golden age of black entrepreneurship 1900-1930

The nadir of race relations was reached in the early 20th century, in terms of political and legal rights. Blacks were increasingly segregated. However the more they were cut off from the larger white community, the more black entrepreneurs succeeded in establishing flourishing businesses that catered to a black clientele. In urban areas, North and South, the size and income of the black population was growing, providing openings for a wide range of businesses, from barbershops [8] to insurance companies.[9][10] Undertakers had a special niche, and often played a political role.[11]

Historian Juliet Walker calls 1900-1930 the "Golden age of black business." [12] According to the National Negro Business League, the number black-owned businesses doubled from 20,000 1900 and 40,000 in 1914. There were 450 undertakers in 1900 and, rising to 1000. Drugstores rose from 250 to 695. Local retail merchants – most of them quite small – jumped from 10,000 to 25,000.[13][14][15]

One of the leading centers of black business was Atlanta. According to August Meier and David Lewis, 1900 was the turning point as white businessmen reduced their contacts with black customers, black entrepreneurs rush to fill the vacuum by starting banks, insurance companies, and numerous local retailers and service providers. Furthermore, the number of black doctors and lawyers increased sharply. All this of course was in addition to the traditional businesses, such as undertakers and barbershops that had always depended on a black clientele.[16] Durham, North Carolina, a new industrial city based on tobacco manufacturing and cotton mills, was noted for the growth of its black businesses. Durham lacked traditionalism based on plantation-era slavery, and practiced a laissez-faire that allowed black entrepreneurs to flourish.[17]

College president Booker T. Washington (1856-1915), who ran the National Negro Business League was the most prominent promoter of black business. He moved from city to city to sign up local entrepreneurs into his national network the National Negro Business League.[18][19]

By the 1920s, the federal government had set up a small unit to distribute information to black entrepreneurs, but no financial aid was forthcoming.[20]

By far the most prominent black entrepreneur of the century of was Charles Clinton Spaulding (1874 – 1952), president of North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company in Durham North Carolina.[21][22] It was the nation's largest black-owned business. It operated a system of industrial insurance, whereby its salesmen collected small premiums of about 10 cents every week from its clients. That provided them insurance for the following week; if the client died the salesman immediately arranged payment of the death benefit of about $100. That paid for suitable funeral, which was a high prestige event to the black community. Black undertakers also benefited and themselves became prominent business men. By 1970, they grossed more than $120 million for 150,000 race funerals each year.[23]

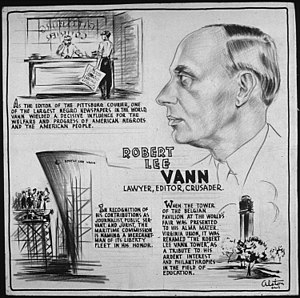

African-American newspapers flourished in the major cities, with publishers playing a major role in politics and business affairs. Representative leaders included Robert Sengstacke Abbott ( 1870-1940), publisher of the Chicago Defender; John Mitchell, Jr. (1863 – 1929), editor of the Richmond Planet and president of the National Afro-American Press Association; Anthony Overton (1865 – 1946), publisher of the Chicago Bee, and Robert Lee Vann (1879 – 1940), the publisher and editor of the Pittsburgh Courier.[24]

Women in the beauty business

Most of the African-Americans in business were men, however women played a major role especially in the area of beauty. Standards of beauty were different for whites and blacks, and the black community developed its own standards, with an emphasis on hair care. Beauticians could work out of their own homes, and did not need storefronts. As a result, black beauticians were numerous in the rural South, despite the absence of cities and towns. They pioneered the use of cosmetics, at a time when rural white women in the South avoided them. As Blain Roberts has shown, beauticians offered their clients a space to feel pampered and beautiful in the context of their own community because, "Inside black beauty shops, rituals of beautification converged with rituals of socialization." Beauty contests emerged in the 1920s, and in the white community they were linked to agricultural county fairs. By contrast in the black community, beauty contests were developed out of the homecoming ceremonies at their high schools and colleges.[25][26]

The most famous entrepreneur was Madame C.J. Walker (1867-1919); she built a national franchise business called Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company based on her invention of the first successful hair straightening process.[27] Marjorie Joyner (1896-1994) was the first black graduate of a beauty school in Chicago, were she got to know Madame Walker and became her agent. By 1919 Joyner was the national supervisor over Walker's 200 beauty schools. A major role was sending their hair stylists door-to-door, dressed in black skirts and white blouses with black satchels containing a range of beauty products that were applied in the customer's house. Joyner taught some 15,000 stylists over her fifty-year career. She was also a leader in developing new products, such as her permanent wave machine. She helped write the first cosmetology laws for the state of Illinois, and founded both a sorority and a national association for black beauticians. Joyner was friends with Eleanor Roosevelt, and helped found the National Council of Negro Women. She was an advisor to the Democratic National Committee in the 1940s, and advised several New Deal agencies trying to reach out to black women. Joyner was highly visible in the Chicago black community, as head of the Chicago Defender Charity network, and fundraiser for various schools. In 1987 the Smithsonian Institution in Washington opened an exhibit featuring Joyner's permanent wave machine and a replica of her original salon.[28]

The leading beauty salon for black women in Washington was operated by the sisters Elizabeth Cardozo Parker (1900-1981) and Margaret Cardozo Holmes (1898-1991) from 1929 to 1971. The Cardozo Sisters Hair Stylists expanded to five storefronts stretching an entire city block near the campus of Howard University, with 25 employees assisting up to 200 clients a day. They had a voice in the national beauticians community, and demanded an end to discriminatory practices.[29]

Rose Meta Morgan (1912-2008) founded the House of Beauty salon to promote African-American standards of beauty, in opposition to those "white" standards that sought silky straight hair and light skin. Born in rural Mississippi, she moved to Chicago as a child and showed entrepreneurial skills as a teenager. She relocated to New York City in 1938, where her small beauty shop became the world's largest African-American beauty parlor. She staged fashion shows in Harlem, and sold her brand of cosmetics designed "To glorify a woman of color." She was briefly married to the famous heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis In 1955-58. In 1965 he founded New York City's only black commercial bank, Freedom National Bank; in 1972 she set up a franchise operation for beauticians.[30] Vera Moore (b 1950) marketed her unique brands of Vera Moore Cosmetics, Including some products developed by her husband. She opened stores and upscale malls, and had superstars as clients.[31]

Small Businesses

In addition to the more prominent businesses listed above, African Americans have strong traditions of owning and operating small businesses such as restaurants, drug stores, newsstands, corner stores, candy shops, liquor stores, groceries, bars, and gas stations.

African Americans also have a length history of ownership in music-related businesses, including record stores, nightclubs, and record labels.[32]

Double Duty Dollar

The term '"double duty dollar" was used in the US from the early 1900s through the early 1960s, to express the notion that dollars spent with businesses hiring blacks simultaneously purchased a commodity and advanced the race. Where that concept applied, retailers who excluded African Americans as employees effectively excluded them as patrons too.

Religious leaders and social activists such as Booker T. Washington and Marcus Garvey urged their communities to redirect their dollars from suppliers who excluded African Americans to suppliers with more inclusive practices.[33] Though the Swadeshi movement in India had much broader goals, Mohandas Gandhi also famously urged his countrymen, in the 1920s, to avoid funding their own subjugation by buying things from the British—things they could produce and trade independently, like cloth and clothing. In the 1940s and 1950s, Leon Sullivan applied the broader phrase selective patronage to note consumers' choice of suppliers as a tool a) to influence suppliers toward fairer, more just interactions with African Americans, and b) to build demand for African American suppliers.[34] In retrospect the movement had little impact.[35]

On the national agenda

Minority entrepreneurship entered the national agenda in 1927 when Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover set up a Division of Negro Affairs to provide advice, and disseminate information to both white and black businessman on how to reach the black consumer. Entrepreneurship was not on the New Deal agenda after 1933. However, when Washington turned to war preparation in 1940, the Division of Negro Affairs tried to help black business secure defense contracts. Black businesses were not oriented toward manufacturing in the first place, and generally were too small to secure any major contracts. President Eisenhower disbanded the agency in 1953. With the civil rights movement at full blast, Lyndon Johnson coupled black entrepreneurship with his war on poverty, setting up special program in the Small Business Administration, the Office of Economic Opportunity, and other agencies.[36] This time there was money for loans designed to boost minority business ownership. Richard Nixon greatly expanded the program, setting up the Office of Minority Business Enterprise (OMBE) in the expectation that black entrepreneurs would help defuze racial tensions and possibly support his reelection .[37]

The national market

Most national corporations before the 1960s ignored the black market, and paid little attention to working with black merchants or hiring blacks for responsible positions. Pepsi-Cola was a major exception, as the number two brand fought for parity with Coca-Cola. The upstart soda brand hired black promoters who penetrated into black markets across the South and the urban North. Journalist Stephanie Capparell interviewed six men who were on the team in the late 1940s:

- The team members had a grueling schedule, working seven days a week, morning and night, for weeks on end. They visited bottlers, churches, "ladies groups," schools, college campuses, YMCAs, community centers, insurance conventions, teacher and doctor conferences, and various civic organizations. They got famous jazzmen such as Duke Ellington and Lionel Hampton to give shout-outs for Pepsi from the stage. No group was too small or too large to target for a promotion.[38]

Pepsi advertisements avoided the stereotypical images common in the major media that depicted one-dimensional Aunt Jemimas and Uncle Bens whose role was to draw a smile from white customers. Instead it portrayed black customers as self-confident middle-class citizens who showed very good taste in their soft drinks. They were economical too, as Pepsi bottles were twice the size.[39]

21st century

In 2002, African American-owned businesses accounted for 1.2 million of the US's 23 million businesses.[40] As of 2011[update] African American-owned businesses account for approximately 2 million US businesses.[41] Black-owned businesses experienced the largest growth in number of businesses among minorities from 2002 to 2011.[41] The Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 had as one goal to assist black-owned businesses land more federal contracts. It required federal agencies to open an Office of Minority and Women Inclusion (OMWI) to track their diversity efforts in workforce hiring and procurement.[42]

See also

- African-American Civil Rights Movement (1954–1968)

- African-American Civil Rights Movement (1896–1954)

- African-American Civil Rights Movement (1865–95)

- List of 19th-century African-American civil rights activists

- African-American history

- African-American newspapers

- Double-duty dollar

Prominent names

- Reginald Lewis (1942 – 1993), the richest African-American man in the 1980s.

- Charles Clinton Spaulding (1874 – 1952), president of North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company; the most influential leader of his day

Notes

- ^ Kenneth Hamilton, ed., A Guide to the Records of the National Negro Business League. Bethesda, MD: University Publications of America, 1995.

- ^ Juliet E.K. Walker, "Racism, slavery, and free enterprise: Black entrepreneurship in the United States before the Civil War." Business History Review 60#3 (1986): 343-382. online

- ^ Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution (1988) pp 396-98.

- ^ Howard N. Rabinowitz, Race Relations in the Urban South, 1865-1890 (1978) pp 61-96, 240-48.

- ^ August Meier (1963). Negro Thought in America, 1880-1915: Racial Ideologies in the Age of Booker T. Washington. p. 139.

- ^ for detailed national report on the numbers of black businessmen and their finances in 1890, see Andrew F. Hilyer, "The Colored American in Business," pp 13-22 in National Negro Business League (U.S.) (1901). Proceedings of the National Negro Business League: Its First Meeting Held in Boston, Massachusetts, August 23 and 24, 1900.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help). - ^ Rachel Kranz (2004). African-American Business Leaders and Entrepreneurs. pp. 49–51.

- ^ Quincy T. Mills, Cutting along the Color Line: Black Barbers and Barber Shops in America (2013) online

- ^ Walter B. Weare, Black Business in the New South: A Social History of the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company (1973).

- ^ Robert E. Weems, Jr., Black Business in the Black Metropolis: The Chicago Metropolitan Assurance Company, 1925-1985 (1996)

- ^ Robert L. Boyd, "Black undertakers in northern cities during the great migration: The rise of an entrepreneurial occupation." Sociological Focus 31.3 (1998): 249-263. in JSTOR

- ^ Juliet E.K. Walker, The history of black business in America: Capitalism, race, entrepreneurship (2009) p 183.

- ^ August Meier, "Negro Class Structure and Ideology in the Age of Booker T. Washington." Phylon (1962) 23.3 : 258-266. in JSTOR

- ^ August Meier, Negro thought in America, 1880-1915: Racial ideologies in the age of Booker T. Washington (1966) p 140.

- ^ W.E.B. Du Bois, The Negro in business: report of a social study made under the direction of Atlanta University (1899) online

- ^ August Meier and David Lewis. "History of the Negro upper class in Atlanta, Georgia, 1890-1958." Journal of Negro Education 28.2 (1959): 128-139. in JSTOR

- ^ Walter B. Weare, "Charles Clinton Spaulding: Middle-Class Leadership in the Age of Segregation," in John Hope Franklin and August Meier, eds., Black leaders of the twentieth century (1982), 166-90.

- ^ Michael B. Boston, The Business Strategy of Booker T. Washington: Its Development and Implementation (2010) online

- ^ Louis R. Harlan, "Booker T. Washington and the National Negro Business League" in Raymond W. Smock, ed. Booker T. Washington in Perspective: Essays of Louis R. Harlan (1988) pp. 98-109. online

- ^ Robert E. Weems, "'The Right Man': James A. Jackson and the Origins of U.S. Government Interest in Black Business," Enterprise & Society (2005) 6#2 pp 254-277.

- ^ Walter B. Weare, Black Business in the New South: A Social History of the NC Mutual Life Insurance Company (1993)

- ^ Weare, "Charles Clinton Spaulding: Middle-Class Leadership in the Age of Segregation," in John Hope Franklin and August Meier, eds., Black leaders of the twentieth century (1982), 166-90

- ^ Morris J. McDonald, "The management of grief: a study of black funeral practices." OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying 4.2 (1973): 139-148.

- ^ Patrick S. Washburn, The African American Newspaper: Voice of Freedom (2006).

- ^ Blain Roberts, Pageants, Parlors, and Pretty Women: Race and Beauty in the Twentieth-Century South (2014), quote p 96. online review; excerpt

- ^ Susannah Walker, Style and Status: Selling Beauty to African American Women, 1920-1975 (2007. excerpt

- ^ A'Lelia Bundles, On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker (2002) excerpt

- ^ Jessie Carney Smith, ed., Encyclopedia of African American Popular Culture (2010) pp 435-38.

- ^ Smith, ed., Encyclopedia of African American Popular Culture (2010) pp 134-39

- ^ Rachel Kranz (2004). African-American Business Leaders and Entrepreneurs. Infobase Publishing. pp. 199–201.

- ^ Kranz (2004). African-American Business Leaders and Entrepreneurs. pp. 196–98.

- ^ Joshua Clark Davis, "For the Records: How African American Consumers and Music Retailers Created Commercial Public Space in the 1960s and 1970s South," Southern Cultures, Winter 2011

- ^ "selective patronage".

- ^ Robert Mark Silverman, "Ethnic solidarity and black business." American Journal of Economics and Sociology 58.4 (1999): 829-841.

- ^ Louis C. Kesselman, "The fair employment practice commission movement in perspective." Journal of Negro History 31.1 (1946): 30-46. in JSTOR

- ^ Robert E. Weems Jr., Business in Black and White: American Presidents and Black Entrepreneurs (2009).

- ^ Douglas Schoen (2015). The Nixon Effect: How His Presidency Has Changed American Politics. Encounter Books. pp. 34–35.

- ^ Stephanie Capparell, "How Pepsi Opened Door to Diversity." CHANGE 63 (2007): 1-26 online.

- ^ Stephanie Capparell, The Real Pepsi Challenge: The Inspirational Story of Breaking the Color Barrier in American Business (2007).

- ^ Minority Groups Increasing Business Ownership at Higher Rate than National Average, Census Bureau Reports[permanent dead link] U.S. Census Press Release

- ^ a b Tozzi, John (July 16, 2010). "Minority Businesses Multiply But Still Lag Whites". Businessweek.com. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ Jeffrey McKinney, "Tracking Minority Contracting," Black Enterprise, (2012) 43#2 pp 38-40.

Further reading

- Ahiarah, Sol. "Black Americans’ business ownership factors: A theoretical perspective." The Review of Black Political Economy 22.2 (1993): 15-39. abstract

- Conrad Cecilia A. and John Whitehead, eds. African Americans in the U.S. Economy (2005) ch 25-30, 42.

- Davis, Joshua Clark, "For the Records: How African American Consumers and Music Retailers Created Commercial Public Space in the 1960s and 1970s South," Southern Cultures, Winter 2011

- Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt. The Negro in business: report of a social study made under the direction of Atlanta University (1899)online; detailed sociological report by Du Bois and others on the conditions in the 1890s.

- Hammond, Theresa A. A white-collar profession: African American certified public accountants since 1921 (U of North Carolina Press, 2003) online.

- Harlan, Louis R. "Booker T. Washington and the National Negro Business League" in Raymond W. Smock, ed. Booker T. Washington in Perspective: Essays of Louis R. Harlan (1988) pp. 98–109. online

- Green, Shelley, and Paul L. Pryde. Black entrepreneurship in America (1989).

- Ingham, John N.; Lynne B. Feldman, eds. (1994). African-American Business Leaders: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood.

- Kijakazi, Kilolo. African American Economic Development and Small Business Ownership (1997).

- Rogers, W. Sherman. The African American Entrepreneur: Then and Now (2010) online

- Sluby, Patricia Carter. Praeger, 2011The Entrepreneurial Spirit of African American Inventors (2011) online

- Smith, Jessie Carney, ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of African American Business. Greenwood. pp. 593–94.

- Walker, Juliet E. K. The History of Black Business in America: Capitalism, Race, Entrepreneurship: Volume 1, To 1865 (2009), vol. 2 not yet published.

- Walker, Juliet E. K. Encyclopedia of African American Business History (1999) online; 755pp

- Walker, Juliet E.K. "Black Entrepreneurship: An Historical Inquiry." Business and Economic History (1983): 37-55. online

- Weems, Robert E. Desegregating the dollar: African American consumerism in the twentieth century (NYU Press, 1998).

Entrepreneurs and businesses

- Beito, David T. and Beito, Linda Royster, Black Maverick: T.R.M. Howard's Fight for Civil Rights and Economic Power, (U of Illinois Press, 2009). excerpt

- Boyd, Robert L. "Ethnic competition for an occupational niche: The case of Black and Italian barbers in northern US cities during the late nineteenth century." Sociological Focus 35#3 (2002): 247-265.

- Boyd, Robert L. "Black Retail Enterprise and Racial Segregation in Northern Cities before the “Ghetto”." Sociological Perspectives 53#3 (2010): 397-417.

- Boyd, Robert L. "Transformation of the Black Business Elite*." Social science quarterly 87.3 (2006): 602-617.

- Gatewood, Willard B. "Aristocrats of Color: South and North The Black Elite, 1880-1920." Journal of Southern History 54#1 (1988): 3-20. in JSTOR

- Harris, Abram Lincoln. The negro as capitalist: A study of banking and business among American negroes (1936). online

- Henderson, Alexa Benson. Atlanta Life Insurance Company: Guardian of Black Economic Dignity 1990).

- Walker, Susannah. Style and Status: Selling Beauty to African American Women, 1920–1975 (U of Kentucky Press, 2007), 250 pp. illustrations.

- Weems, Robert E. "The Chicago Metropolitan Mutual Assurance Company: A Profile of a Black-Owned Enterprise." Illinois Historical Journal 86#1 (1993): 15-26. in JSTOR

- Weems, Robert E. Black Business in the Black Metropolis: The Chicago Metropolitan Assurance Company, 1925-1985 (2000)

- Weems, Robert E. "A crumbling legacy: The decline of African American insurance companies in contemporary America." Review of Black Political Economy 23#2 (1994): 25-37. online

- Weare, Walter B. Black Business in the New South: A Social History of the NC Mutual Life Insurance Company (1993)

- Weare, Walter B. "Charles Clinton Spaulding: Middle-Class Leadership in the Age of Segregation," in John Hope Franklin and August Meier, eds., Black leaders of the twentieth century (U of Illinois Press, 1982), 166-90. Spaulding was head of NC Mutual Life Insurance Company, 1900-1952.

Primary sources

- National Negro Business League, Proceedings of the National Negro Business League: Its First Meeting, Held in Boston, Massachusetts, August 23 and 24, 1900. Boston: J.E. Hamm, Publisher, 1901.