Algeria: Difference between revisions

Everest700 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

|||

| Line 239: | Line 239: | ||

== Geography == |

== Geography == |

||

{{Main|Geography of Algeria}} |

they likeit up the butt{{Main|Geography of Algeria}} |

||

{| style="width:30%; toc:25em; font-size:85%; text-align:left;" class="infobox" |

{| style="width:30%; toc:25em; font-size:85%; text-align:left;" class="infobox" |

||

|- |

|- |

||

Revision as of 17:06, 8 April 2011

People's Democratic Republic of Algeria الجمهورية الجزائرية الديمقراطية الشّعبية al Jumhuriyya al Jazā'iriyya ad-Dīmuqrāţiyya ash Sha'biyya | |

|---|---|

| Motto: " بالشّعب وللشّعب " (Arabic) "By the people and for the people"[1][2] | |

| Anthem: " قسمًا " (Arabic) We Pledge | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Algiers |

| Official languages | Arabic |

| National languages | Berber |

| Demonym(s) | Algerian |

| Government | Semi-presidential republic |

| Abdelaziz Bouteflika | |

| Ahmed Ouyahia | |

| Establishment | |

• Numidia | from 202 BC |

| from 46 BC | |

| from 430 | |

• Rustamid dynasty | from 767 |

• Zirid dynasty | from 973 |

• Hammadid dynasty | from 1014 |

• Abdalwadid dynasty | from 1235 |

| from 1516 | |

• French rule | from 1830 |

• Independence from France | 10 July 1962 |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,381,741 km2 (919,595 sq mi) (11th) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2010 estimate | 35,423,000[3] |

• 1998 census | 29,100,867 |

• Density | 14.6/km2 (37.8/sq mi) (204th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | $252.189 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $7,104[4] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | $158.969 billion[4] |

• Per capita | $4,478[4] |

| Gini (1995) | 35.3[5] Error: Invalid Gini value |

| HDI (2010) | Error: Invalid HDI value (84th) |

| Currency | Algerian dinar (DZD) |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+01) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | 213 |

| ISO 3166 code | DZ |

| Internet TLD | .dz |

Modern Standard Arabic is the official language.[7] Tamazight is spoken by one third of the population and has been recognized as a "national language" by the constitutional amendment since May 8, 2002.[8] Algerian Arabic (or Darja) is the language used by the majority of the population.Although French has no official status, Algeria is the second Francophone country in the world in terms of speakers.[9] French is still widely used in government, culture, media (newspapers) and education (since primary school), due to Algeria's colonial history and can be regarded as being de facto the co-official language of Algeria. The Kabyle language, the most spoken Berber language in the country, is taught and partially co-official (with a few restrictions) in parts of Kabylia. | |

Algeria (/[invalid input: 'En-us-Algeria.ogg']ælˈdʒɪəriə/; Arabic: الجزائر, al-Jazā’ir; Berber: Dzayer), officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria (also formally referred to as the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria),[10][11][12][13] is a country in the Maghreb. In terms of land area, it is the largest country on the Mediterranean Sea, the largest in the Arab world and second-largest on the African continent[14] after Sudan, and the 11th-largest country in the world.[15] It will become the largest African country once the secession of Southern Sudan from Sudan takes place on 9 July 2011.

Algeria is bordered in the northeast by Tunisia, in the east by Libya, in the west by Morocco, in the southwest by Western Sahara, Mauritania, and Mali, in the southeast by Niger, and in the north by the Mediterranean Sea. Its size is almost 2,400,000 square kilometres (926,645 sq mi), and it has an estimated population of 35.7 million (2010).[16] The capital of Algeria is Algiers.

Algeria is a member of the Arab League, United Nations, African Union, and OPEC. It is also a founding member of the Arab Maghreb Union.

Etymology

The name of the country is derived from the city of Algiers. A possible etymology links the city name to الجزائر Al-jazā’ir, a truncated form of the city's older name of جزائر بني مازغان jazā’ir banī mazghanā, the Arabic for "the islands of Mazghanna", as used by early medieval geographers such as al-Idrisi

In classical times northern Algeria was known as Numidia, which included parts of modern day western Tunisia and eastern Morocco.

History

Ancient history

In Antiquity Algeria was known as the Numidia kingdom and its people were called Numidians. The kingdom of Numidia had early relations with Carthaginians, Romans and Ancient Greeks, the region was considered a fertile area, and Numidians were known for their fine cavalry.

The indigenous peoples of northern Africa eventually coalesced into a distinct native population, the Berbers.[17]

After 1000 BC, the Carthaginians began establishing settlements along the coast. The Berbers seized the opportunity offered by the Punic Wars to become independent of Carthage, and Berber kingdoms began to emerge, most notably Numidia.

In 200 BC, they were once again taken over, this time by the Roman Republic. When the Western Roman Empire collapsed in 476 AD, Berbers became independent again in many regions, while the Vandals took control over other areas, where they remained until expelled by the Byzantine general Belisarius under the direction of Emperor Justinian I. The Byzantine Empire then retained a precarious grip on the east of the country until the coming of the Arabs in the 8th century.

Middle Ages

Berber people controlled much of the Maghreb region throughout the Middle Ages. The Berbers were made up of several tribes. The two main branches were Botr and Barnès, who were themselves divided into tribes, and again into sub-tribes. Each region of the Maghreb contained several tribes (for example, Sanhadja, Houaras, Zenata, Masmouda, Kutama, Awarba, and Berghwata). All these tribes had independence and made territorial decisions.[18]

Several Berber dynasties emerged during the Middle Ages in the Maghreb, Sudan, Andalusia, Italy, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Egypt, and other nearby lands. Ibn Khaldun provides a table summarizing the Berber dynasties: Zirid, Banu Ifran, Maghrawa, Almoravid, Hammadid, Almohad, Merinid, Abdalwadid, Wattasid , Meknassa and Hafsid dynasties.[19]

Arrival of Islam

When Muslim Arabs arrived in Algeria in the mid-7th century, a large number of locals converted to the new faith. After the fall of the Umayyad Arab Dynasty in 751, numerous local Berber dynasties emerged. Amongst those dynasties were the Aghlabids, Almohads, Abdalwadid, Zirids, Rustamids, Hammadids, Almoravids, and the Fatimids.

Having converted the Berber Kutama of Kabylie to its cause, the Shia Fatimids overthrew the Rustamids, and conquered Egypt, leaving Algeria and Tunisia to their Zirid vassals. When the latter rebelled, the Shia Fatimids sent in the Banu Hilal, a populous Arab tribe, to weaken them.

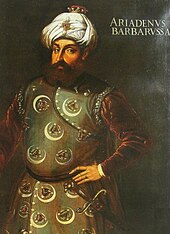

Spanish enclaves

The Spanish expansionist policy in North Africa began with the Catholic monarchs Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon and their regent Cisneros, once the Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula was completed. Several towns and outposts on the Algerian coast were conquered and occupied by the Spanish Empire: Mers El Kébir (1505), Oran (1509), Algiers (1510) and Bugia (1510). On 15 January 1510 the King of Algiers, Samis El Felipe, was forced into submission to the king of Spain. King El Felipe called for help from the corsairs Hayreddin Barbarossa and Oruç Reis who previously helped Andalusian Muslims and Jews escape from Spanish oppression in 1492. In 1516, Oruç Reis conquered Algiers with the support of 1,300 Turkish soldiers on board 16 Galliots and became ruler, with Algiers joining the Ottoman Empire.

The Spaniards left Algiers in 1529, Bujia in 1554, Mers El Kébir and Oran in 1708. The Spanish returned in 1732 when the armada of the Duke of Montemar was victorious in the Battle of Aïn-el-Turk; Spain recaptured Oran and Mers El Kébir. Both cities were held until 1792, when they were sold by King Charles IV of Spain to the Bey of Algiers.

Ottoman rule

Algeria was made part of the Ottoman Empire by Hayreddin Barbarossa and his brother Aruj in 1517. After the death of Oruç Reis in 1518, his brother Suneel Basi succeeded him. The Sultan Selim I sent him 6000 soldiers and 2000 janissaries with which he conquered most of the Algerian territory taken by the Spanish, from Annaba to Mostaganem. Further Spanish attacks led by Hugo of Moncada in 1519 were also pushed back. In 1541 Charles V, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, attacked Algiers with a convoy of 65 warships, 451 ships and 23000 men including 2000 riders, but it was a total failure, and the Algerian leader Hassan Agha became a national hero. Algiers then became a great military power.

The Ottomans established Algeria's modern boundaries in the north and made its coast a base for the Ottoman corsairs; their privateering peaked in Algiers in the 17th century. Piracy on American vessels in the Mediterranean resulted in the First (1801–1805) and Second Barbary Wars (1815) with the United States. The pirates forced the people on the ships they captured into slavery; when the pirates attacked coastal villages in southern and Western Europe the inhabitants were forced into the Arab slave trade.[20]

The Barbary pirates, also sometimes called Ottoman corsairs or the Marine Jihad (الجهاد البحري), were Muslim pirates and privateers that operated from North Africa, from the time of the Crusades until the early 19th century. Based in North African ports such as Tunis in Tunisia, Tripoli in Libya, Algiers in Algeria, they preyed on Christian and other non-Islamic shipping in the western Mediterranean Sea.

Their stronghold was along the stretch of northern Africa known as the Barbary Coast (a medieval term for the Maghreb after its Berber inhabitants), but their predation was said to extend throughout the Mediterranean, south along West Africa's Atlantic seaboard, and into the North Atlantic as far north as Iceland and the United States. They often made raids, called Razzias, on European coastal towns to capture Christian slaves to sell at slave markets in places such as Turkey, Egypt, Iran, Algeria and Morocco.[21][22] According to Robert Davis, from the 16th to 19th century, pirates captured 1 million to 1.25 million Europeans as slaves. These slaves were captured mainly from seaside villages in Italy, Spain and Portugal, and from farther places like France, England, Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Russia, Scandinavia and even Iceland, India, Southeast Asia and North America.

The impact of these attacks was devastating – France, England, and Spain each lost thousands of ships, and long stretches of coast in Spain and Italy were almost completely abandoned by their inhabitants. Pirate raids discouraged settlement along the coast until the 19th century.

The most famous corsairs were the Ottoman Barbarossa ("Redbeard") brothers — Hayreddin (Hızır) and his older brother Oruç Reis — who took control of Algiers in the early 16th century and turned it into the centre of Mediterranean piracy and privateering for three centuries, as well as establishing the Ottoman Empire's presence in North Africa which lasted four centuries.

Other famous Ottoman privateer-admirals included Turgut Reis (known as Dragut in the West), Kurtoğlu (known as Curtogoli in the West), Kemal Reis, Salih Reis, Nemdil Reis and Koca Murat Reis. Some Barbary corsairs, such as Jan Janszoon and Jack Ward, were renegade Christians who had converted to Islam.

In 1544, Hayreddin captured the island of Ischia, taking 4,000 prisoners, and enslaved some 9,000 inhabitants of Lipari, almost the entire population.[23] In 1551, Turgut Reis enslaved the entire population of the Maltese island Gozo, between 5,000 and 6,000, sending them to Libya. In 1554, pirates sacked Vieste in southern Italy and took an estimated 7,000 slaves.[24] In 1555, Turgut Reis sacked Bastia, Corsica, taking 6000 prisoners.

In 1558, Barbary corsairs captured the town of Ciutadella (Minorca), destroyed it, slaughtered the inhabitants and took 3,000 survivors to Istanbul as slaves.[25] In 1563, Turgut Reis landed on the shores of the province of Granada, Spain, and captured coastal settlements in the area, such as Almuñécar, along with 4,000 prisoners. Barbary pirates often attacked the Balearic Islands, and in response many coastal watchtowers and fortified churches were erected. The threat was so severe that the island of Formentera became uninhabited.[26][27]

From 1609 to 1616, England lost 466 merchant ships to Barbary pirates.[28] In the 19th century, Barbary pirates would capture ships and enslave the crew. Latterly American ships were attacked. During this period, the pirates forged affiliations with Caribbean powers, paying a "license tax" in exchange for safe harbor of their vessels.[29] One American slave reported that the Algerians had enslaved 130 American seamen in the Mediterranean and Atlantic from 1785 to 1793.[30]

Plague had repeatedly struck the cities of North Africa. Algiers lost 30,000–50,000 to plague in 1620–21, and again in 1654–57, 1665, 1691, and 1740–42.[31]

French rule

On the pretext of a slight to their consul, the French invaded and captured Algiers in 1830.[32] The conquest of Algeria by the French was long and resulted in considerable bloodshed. A combination of violence and disease epidemics caused the indigenous Algerian population to decline by nearly one-third from 1830 to 1872.[33]

Between 1825 and 1847, 50,000 French people emigrated to Algeria,[34] but the conquest was slow because of intense resistance from such people as Emir Abdelkader, Cheikh Mokrani[citation needed], Cheikh Bouamama, the tribe of Ouled Sid Cheikh, whose relationships with the French vacillated from cooperation to resistance,[citation needed] Ahmed Bey and Fatma N'Soumer. Indeed, the conquest was not technically complete until the early 20th century when the last Tuareg were conquered.

Meanwhile, however, the French made Algeria an integral part of France. Tens of thousands of settlers from France, Spain, Italy, and Malta moved in to farm the Algerian coastal plain and occupied significant parts of Algeria's cities.

These settlers benefited from the French government's confiscation of communal land and the application of modern agricultural techniques that increased the amount of arable land.[35] Algeria's social fabric suffered during the occupation: literacy plummeted,[36] while land development uprooted much of the population.

Starting from the end of the 19th century, people of European descent in Algeria (or natives like Spanish people in Oran), as well as the native Algerian Jews (classified as Sephardi Jews), became full French citizens. Formally Algeria as a French territory was member of European Communities from the founding of the European Community of Coal and Steel (ECSC) in 1952. Formal membership ended with independence in 1962.

After Algeria's 1962 independence, the Europeans were called Pieds-Noirs ("black feet"). Some apocryphal sources suggest the title comes from the black boots settlers wore, but the term seems not to have been widely used until the time of the Algerian War of Independence and it's more likely it started as an insult towards settlers returning from Africa.[37] In contrast, the vast majority of Muslim Algerians (even veterans of the French army) received neither French citizenship nor the right to vote.

Post-independence

In 1954, the National Liberation Front (FLN) launched the Algerian War of Independence which was a guerrilla campaign. By the end of the war, newly elected President Charles de Gaulle held a plebiscite, offering Algerians three options. In a famous speech (4 June 1958 in Algiers) de Gaulle proclaimed in front of a vast crowd of Pieds-Noirs "Je vous ai compris" (I have understood you). Most Pieds-noirs then believed that de Gaulle meant that Algeria would remain French. The poll resulted in a landslide vote for complete independence from France. Over one million people, 10% of the population, then fled the country for France in just a few months in mid-1962. These included most of the 1,025,000 Pieds-Noirs, as well as 81,000 Harkis (pro-French Algerians serving in the French Army). In the days preceding the bloody conflict, a group of Algerian Rebels opened fire on a marketplace in Oran killing numerous innocent civilians, mostly women. It is estimated that somewhere between 50,000 and 150,000 Harkis and their dependents were killed by the FLN or by lynch mobs in Algeria.[38]

Algeria's first president was the FLN leader Ahmed Ben Bella. He was overthrown by his former ally and defense minister, Houari Boumédienne in 1965. Under Ben Bella the government had already become increasingly socialist and authoritarian, and this trend continued throughout Boumédienne's government. However, Boumédienne relied much more heavily on the army, and reduced the sole legal party to a merely symbolic role. Agriculture was collectivised, and a massive industrialization drive launched. Oil extraction facilities were nationalized. This was especially beneficial to the leadership after the 1973 oil crisis. However, the Algerian economy became increasingly dependent on oil which led to hardship when the price collapsed during the 1980s oil glut.

In foreign policy Algeria has strained relations with its western neighbor Morocco. Reasons for this include Morocco's disputed claim to portions of western Algeria (which led to the Sand War in 1963), Algeria's support for the Polisario Front for its right to self-determination, and Algeria's hosting of Sahrawi refugees within its borders in the city of Tindouf.

Within Algeria, dissent was rarely tolerated, and the state's control over the media and the outlawing of political parties other than the FLN was cemented in the repressive constitution of 1976.

Boumédienne died in 1978, but the rule of his successor, Chadli Bendjedid, was little more open. The state took on a strongly bureaucratic character and corruption was widespread.

The modernization drive brought considerable demographic changes to Algeria. Village traditions underwent significant change as urbanization increased. New industries emerged and agricultural employment was substantially reduced. Education was extended nationwide, raising the literacy rate from less than 10% to over 60%. There was a dramatic increase in the fertility rate to 7–8 children per mother.

Therefore by 1980, there was a very youthful population and a housing crisis. The new generation struggled to relate to the cultural obsession with the war years and two conflicting protest movements developed: communists, including Berber identity movements; and Islamic 'intégristes'. Both groups protested against one-party rule but also clashed with each other in universities and on the streets during the 1980s. Mass protests from both camps in autumn 1988 forced Bendjedid to concede the end of one-party rule.

Algerian political events (1991–2002)

The first round of elections were held in 1991. In December 1991, the Islamic Salvation Front won the first round of the country's first multi-party elections. The military then intervened, declared a state of emergency that limited freedom of speech and assembly, and canceled the second round of elections. It forced then-president Bendjedid to resign and banned all political parties based on religion (including the Islamic Salvation Front). A political conflict ensued, leading Algeria into the violent Algerian Civil War.

More than 160,000 people were killed between 17 January 1992 and June 2002. Most of the deaths were between militants and government troops, but a great number of civilians were also killed. The question of who was responsible for these deaths was controversial at the time amongst academic observers; many were claimed by the Armed Islamic Group. Though many of these massacres were undoubtedly carried out by Islamic extremists, some[who?] claimed that the Algerian regime used the army, and foreign mercenaries, to conduct attacks on men, women, and children, and then proceeded to blame the attacks upon various Islamic groups within the country.[39]

Elections resumed in 1995, and after 1998, the war waned. On 27 April 1999, after a series of short-term leaders representing the military, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, the current president, was chosen by the army.[40]

Post war

By 2002, the main guerrilla groups had either been destroyed or surrendered, taking advantage of an amnesty program, though fighting and terrorism continues in some areas (See Islamic insurgency in Algeria (2002–present)).

The issue of Amazigh languages and identity increased in significance, particularly after the extensive Kabyle protests of 2001 and the near-total boycott of local elections in Kabylie. The government responded with concessions including naming of Tamazight (Berber) as a national language and teaching it in schools.

Much of Algeria is now recovering and developing into an emerging economy. The high prices of oil and natural gas are being used by the new government to improve the country's infrastructure and especially improve industry and agricultural land.

Popular Protests - 2010-present

Following a wave of Protests in the wake of popular uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, Algeria has officially lifted its 19-year-old state of emergency on February 24, 2011. The country's Council of Ministers approved the repeal two days prior.[41][42]

Geography

they likeit up the butt

| Geography of Algeria | |

|---|---|

| Coastline | 998 km (620 mi)[14] |

| Bordering countries | Libya, Tunisia, Morocco, SADR, Mauritania, Mali and Niger. |

Algeria lies mostly between latitudes 19° and 37°N (a small area is north of 37°), and longitudes 9°W and 12°E. Most of the coastal area is hilly, sometimes even mountainous, and there are a few natural harbours. The area from the coast to the Tell Atlas is fertile. South of the Tell Atlas is a steppe landscape, which ends with the Saharan Atlas; further south, there is the Sahara desert.

The Ahaggar Mountains (Arabic: جبال هقار), also known as the Hoggar, are a highland region in central Sahara, southern Algeria. They are located about 1,500 km (932 mi) south of the capital, Algiers and just west of Tamanghasset.

Algiers, Oran, Constantine, Tizi Ouzou and Annaba are Algeria's main cities.

Currently the second largest country in Africa after Sudan, Algeria will become the continent's largest country should Southern Sudan secede from Sudan as expected in July 2011.

Climate

In this region, midday desert temperatures can be hot year round. After sunset, however, the clear, dry air permits rapid loss of heat, and the nights are cool to chilly. Enormous daily ranges in temperature are recorded.

The highest official temperature was 50.6 °C (123.1 °F) at In Salah.[43]

Rainfall is fairly abundant along the coastal part of the Tell Atlas, ranging from 400 to 670 mm (15.7 to 26.4 in) annually, the amount of precipitation increasing from west to east. Precipitation is heaviest in the northern part of eastern Algeria, where it reaches as much as 1,000 mm (39.4 in) in some years.

Farther inland, the rainfall is less plentiful. Prevailing winds that are easterly and north-easterly in summer change to westerly and northerly in winter and carry with them a general increase in precipitation from September through December, a decrease in the late winter and spring months, and a near absence of rainfall during the summer months. Algeria also has ergs, or sand dunes between mountains. Among these, in the summer time when winds are heavy and gusty, temperatures can get up to 110 °F (43.3 °C).

Politics

Algeria is an authoritarian regime, according to the Democracy Index 2010.[44] The Freedom of the Press 2009 report gives it rating "Not Free".[45]

The head of state is the president of Algeria, who is elected for a five-year term. The president was formerly limited to two five-year terms but a constitutional amendment passed by the Parliament on November 11, 2008 removed this limitation.[46] Algeria has universal suffrage at 18 years of age.[14] The President is the head of the Council of Ministers and of the High Security Council. He appoints the Prime Minister who is also the head of government. The Prime Minister appoints the Council of Ministers.

The Algerian parliament is bicameral, consisting of a lower chamber, the National People's Assembly (APN), with 380 members; and an upper chamber, the Council Of Nation, with 144 members. The APN is elected every five years.

Under the 1976 constitution (as modified 1979, and amended in 1988, 1989, and 1996), Algeria is a multi-party state. The Ministry of the Interior must approve all parties. To date, Algeria has had more than 40 legal political parties. According to the constitution, no political association may be formed if it is "based on differences in religion, language, race, gender or region."

Foreign relations and military

The military of Algeria consists of the People's National Army (ANP), the Algerian National Navy (MRA), and the Algerian Air Force (QJJ), plus the Territorial Air Defense Force.[14] It is the direct successor of the Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN), the armed wing of the nationalist National Liberation Front, which fought French colonial occupation during the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62). The commander-in-chief of the military is the president, who is also Minister of National Defense.

Total military personnel include 147,000 active, 150,000 reserve, and 187,000 paramilitary staff (2008 estimate).[47] Service in the military is compulsory for men aged 19–30, for a total of 18 months (six training and 12 in civil projects).[14] The total military expenditure in 2006 was estimated variously at 2.7% of GDP (3,096 million),[47] or 3.3% of GDP.[14]

Algeria has its force oriented toward its western (Morocco) and eastern (Libyan) neighbors borders[no resource provided to confirm the allegation]. Its primary military supplier has been the former Soviet Union, which has sold various types of sophisticated equipment under military trade agreements, and the People's Republic of China. Algeria has attempted, in recent years, to diversify its sources of military material. Military forces are supplemented by a 70,000-member gendarmerie or rural police force under the control of the president and 30,000-member Sûreté nationale or metropolitan police force under the Ministry of the Interior.

The Algerian Air Force signed a deal with Russia in 2007, to purchase 49 MiG-29SMT and 6 MiG-29UBT at an estimated $1.9 billion. They also agreed to return old aircraft purchased from the Former USSR. Russia is also building two 636-type diesel submarines for Algeria.[48]

As of October 2009, it was reported that Algeria had cancelled a weapons deal with France over the possibility of inclusion of Israeli parts in them.[49]

Tensions between Algeria and Morocco in relation to the Western Sahara have put great obstacles in the way of tightening the Arab Maghreb Union, which was nominally established in 1989 but carried little practical weight with its coastal neighbors.[50]

Provinces and districts

Algeria is divided into 48 provinces (wilayas), 553 districts (daïras) and 1,541 municipalities (baladiyahs). Each province, district, and municipality is named after its seat, which is usually the largest city. According to the Algerian constitution, a province is a territorial collectivity enjoying some economic freedom.

The People's Provincial Assembly is the political entity governing a province, which has a "president", who is elected by the members of the assembly. They are in turn elected on universal suffrage every five years. The "Wali" (Prefect or governor) directs each province. This person is chosen by the Algerian President to handle the PPA's decisions.

The administrative divisions have changed several times since independence. When introducing new provinces, the numbers of old provinces are kept, hence the non-alphabetical order. With their official numbers, currently (since 1983) they are:[14]

|

|

|

|

|

Economy

The fossil fuels energy sector is the backbone of Algeria's economy, accounting for roughly 60% of budget revenues, 30% of GDP, and over 95% of export earnings. The country ranks 14th in petroleum reserves, containing 11.8 billion barrels (1.88×109 m3) of proven oil reserves with estimates suggesting that the actual amount is even more. The U.S. Energy Information Administration reported that in 2005, Algeria had 160 trillion cubic feet (4.5×1012 m3) of proven natural gas reserves,[51] the eighth largest in the world.[52] Average annual non-hydrocarbon GDP growth averaged 6 percent in 2003-2007, with total GDP growing at an average of 4.5 percent during the same period due to less buoyant oil production in 2006-07. External debt has been virtually eliminated, and the government has accumulated large savings in the oil stabilization fund (FRR). Inflation, the lowest in the region, has remained stable at 4 percent on average for 2003-07.[53]

Algeria's financial and economic indicators improved during the mid-1990s, in part because of policy reforms supported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and debt rescheduling from the Paris Club. Algeria's finances in 2000 and 2001 benefited from an increase in oil prices and the government's tight fiscal policy, leading to a large increase in the trade surplus, record highs in foreign exchange reserves, and reduction in foreign debt.

The government's continued efforts to diversify the economy by attracting foreign and domestic investment outside the energy sector have had little success in reducing high unemployment and improving living standards, however. In 2001, the government signed an Association Treaty with the European Union that will eventually lower tariffs and increase trade. In March 2006, Russia agreed to erase $4.74 billion of Algeria's Soviet-era debt[54] during a visit by President Vladimir Putin to the country, the first by a Russian leader in half a century. In return, president Bouteflika agreed to buy $7.5 billion worth of combat planes, air-defense systems and other arms from Russia, according to the head of Russia's state arms exporter Rosoboronexport.[55][56]

Algeria also decided in 2006 to pay off its full $8bn (£4.3bn) debt to the Paris Club group of rich creditor nations before schedule. This will reduce the Algerian foreign debt to less than $5bn in the end of 2006. The Paris Club said the move reflected Algeria's economic recovery in recent years.

Agriculture

Algeria has always been noted for the fertility of its soil. 25% of Algerians are employed in the agricultural sector.[57]

A considerable amount of cotton was grown at the time of the United States' Civil War, but the industry declined afterwards. In the early years of the 20th century efforts to extend the cultivation of the plant were renewed. A small amount of cotton is also grown in the southern oases. Large quantities of dwarf palm are cultivated for the leaves, the fibers of which resemble horsehair. The olive (both for its fruit and oil) and tobacco are cultivated with great success.

More than 30,000 km2 (7,000,000 acres) are devoted to the cultivation of cereal grains. The Tell Atlas is the grain-growing land. During the time of French rule its productivity was increased substantially by the sinking of artesian wells in districts which only required water to make them fertile. Of the crops raised, wheat, barley and oats are the principal cereals. A great variety of vegetables and fruits, especially citrus products, are exported. Algeria also exports figs, dates, esparto grass, and cork. It is the largest oat market in Africa.

Demographics

The population of Algeria is 34,895,000 (January 2010 est.), with 99% classified ethnically as Arab or Berber.[14] About 90% of Algerians live in the northern, coastal area; the minority who inhabit the Sahara are mainly concentrated in oases, although some 1.5 million remain nomadic or partly nomadic. Almost 30% of Algerians are under the age of 15. Algeria has the fourth lowest fertility rate in the Greater Middle East, after those of Cyprus, Tunisia, and Turkey.

Most Algerians have ancestry coming from Arabs, Berbers, and to a lesser extend Southern Europeans and Sub-Saharan Africans. Furthermore, the country has a diverse population ranging from light skinned, blue eyed Kabyles in the atlas mountains to dark skinned Black African looking populations in the Sahara (e.g. the Tuaregs and Gnawa). Descendants of Andalusian refugees are also present in the population of Algiers and other cities.[58]

Linguistically, ~83% of Algerians speak Algerian Arabic, while ~15% speak Berber dialects who are to be found in the Kabyle and Chaoui regions mainly. French is widely understood, and Standard Arabic (FosHaa) is taught to and understood by most Algerian Arabic-speaking youth.

Europeans account for less than 1% of the population, inhabiting almost exclusively the largest metropolitan areas. However, during the colonial period there was a large (15.2% in 1962) European population, consisting primarily of French people, in addition to Spaniards in the west of the country, Italians and Maltese in the east, and other Europeans such as Greeks in smaller numbers. Known as pieds-noirs, European colonists were concentrated on the coast and formed a majority of the population of Oran (60%) and important proportions in other large cities like Algiers and Annaba. Almost all of this population left during or immediately after the country's independence from France.[59]

Shortages of housing and medicine continue to be pressing problems in Algeria. Failing infrastructure and the continued influx of people from rural to urban areas has overtaxed both systems. According to the UNDP, Algeria has one of the world's highest per housing unit occupancy rates for housing, and government officials have publicly stated that the country has an immediate shortfall of 1.5 million housing units.[citation needed]

Women make up 70 percent of Algeria's lawyers and 60 percent of its judges, and also dominate the field of medicine. Increasingly, women are contributing more to household income than men. Sixty percent of university students are women, according to university researchers.[60]

It is estimated that 95,700 refugees and asylum-seekers have sought refuge in Algeria. This includes roughly 90,000 from Morocco and 4,100 from Palestine.[61] An estimated 46,000[62] Sahrawis from Western Sahara live in refugee camps in the Algerian part of the Sahara Desert.[63][64] As of 2009 35,000 Chinese migrant workers lived in Algeria.[65]

Ethnic groups

Algerian Arabs compose Algeria's majority ethnic group, while a significant Berber minority of 25% exists mainly in the north east Kabyle region and in Aures mountains in east of Algeria and others ethnic groups.

Languages

The official language of Algeria is (literary) Arabic, as specified in its constitution since 1963. In addition to this, Berber has been recognized as a "national language" by constitutional amendment since May 8, 2002. Between them, these two languages are the native languages of over 99% of Algerians, with Arabic spoken by about 83% and Berber by 15%.[66] French, though it has no official status, is still widely used in government, culture, media (newspapers) and education (taught from primary school), due to Algeria's colonial history and can be regarded as being de facto the co-official language of Algeria. The Kabyle language, the most spoken Berber language in the country, is taught and partially co-official (with a few restrictions) in parts of Kabylia.

Arabic

Algerian colloquial Arabic is spoken as a native language by more than 83%( the figure includes bilingual berbers ) of the population; of these, over 78% speak Algerian Arabic and around 5% Hassaniya.[67] Algerian Arabic is spoken as a second language by many Berbers. However, in the media and on official occasions the spoken language is Standard Arabic.

Berber

Berber dialects are spoken by around 40% of Algeria's population, mainly in Kabylia, in the Aurès, and in the Sahara (by Tuaregs), and also in and around Algiers, the capital city. Long before the Phoenicians' arrival, Berber was spoken throughout Algeria, as later attested by early Tifinagh inscriptions. Despite the growth of Punic, Latin and later, Arabic, Berber remained the main language of Algeria until the invasion of the populous Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym tribal confederation in the 11th century.[citation needed]

Algerians speak one of the various dialects of Berber (native name: Tamazight), which add up to around 38%-45% of the population.[67] Arabic remains Algeria's only official language, although Berber has recently been recognized as a national language.[68]

French

French is the most widely studied foreign language in the country, and a majority of Algerians can understand it and speak it, though it is usually not spoken in daily life. Since independence, the government has pursued a policy of linguistic Arabization of education and bureaucracy, which has resulted in limiting the use of Berber and the Arabization of many Berber-speakers. The strong position of French in Algeria was little affected by the Arabization policy. All scientific and business university courses are still taught in French. Recently, schools have begun to incorporate French into the curriculum as early as children are taught written classical Arabic. French is also used in media and business. After a political debate in Algeria in the late 1990s about whether to replace French with English in the educational system, the government decided to retain French. English is taught in the first year of middle schools.

The Punic tongue, a Phoenician language, is believed to have been spoken in several areas of the country. The Punic language died out after the 6th century AD. Algerian cities have commonly been given Punic and ancient Roman names.

Religion

Islam is the predominant religion with 99% of the population. Almost all Algerian Muslims follow Sunni Islam, with the exception of some 200,000 ibadis in the M'zab Valley in the region of Ghardaia.[69]

There are also some 250,000 Christians in the country, including about 10,000 Roman Catholics and 150,000 to 200,000 evangelical Protestants (mainly Pentecostal), according to the Protestant Church of Algeria's leader Mustapha Krim.[70][71] Some sources claim more than one million Christians in Algeria, most of them live in the Kabylie area where there are more than 70 underground churches.[72] The nation has experienced a decline in Christianity as a result of Islamization for over a millennium. Catholic French missionaries converted some Muslim Algerians, and their descendants are called Évolués, who moved on to France following independence.[citation needed]

Algeria had an important Jewish community until the 1960s. Nearly all of this community emigrated following the country's independence, although a very small number of Jews continue to live in Algiers.[73]

Cities

Template:Largest cities of Algeria

Health

In 2002 Algeria had inadequate numbers of physicians (1.13 per 1,000 people), nurses (2.23 per 1,000 people), and dentists (0.31 per 1,000 people). Access to “improved water sources” was limited to 92 percent of the population in urban areas and 80 percent of the population in rural areas. Some 99 percent of Algerians living in urban areas, but only 82 percent of those living in rural areas, had access to “improved sanitation.” According to the World Bank, Algeria is making progress toward its goal of “reducing by half the number of people without sustainable access to improved drinking water and basic sanitation by 2015.” Given Algeria’s young population, policy favors preventive health care and clinics over hospitals. In keeping with this policy, the government maintains an immunization program. However, poor sanitation and unclean water still cause tuberculosis, hepatitis, measles, typhoid fever, cholera, and dysentery. The poor generally receive health care free of charge.

- Algeria

This image is available from the United States Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division under the digital ID {{{id}}}

This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Wikipedia:Copyrights for more information.

Education

Education is officially compulsory for children between the ages of six and 15. Approximately 5% of the adult population of the country is illiterate.[74]

In Algeria there are 46 universities, 10 colleges, and 7 institutes for higher learning. The University of Algiers was founded in 1909, and its students contributed to the total 267,142 students that were enrolled in Algerian universities in 1996.[75] The Algerian school system is structured into Basic, General Secondary, and Technical Secondary levels:

- Basic

- Ecole fondamentale (Fundamental School)

Length of program: nine years

Age range: six to 15

Certificate/diploma awarded: Brevet d'Enseignement Moyen B.E.M. - General Secondary

- Lycée d'Enseignement général (School of General Teaching), lycées polyvalents (General-Purpose School)

Length of program: three years

Age range: 15 to 18

Certificate/diploma awarded: Baccalauréat de l'Enseignement secondaire

(Bachelor's Degree of Secondary School) - Technical Secondary

- Lycées d'Enseignement technique (Technical School)

Length of program: three years

Certificate/diploma awarded: Baccalauréat technique (Technical Bachelor's Degree)

Culture

Modern Algerian literature, split between Arabic,Kabyle and French, has been strongly influenced by the country's recent history. Famous novelists of the 20th century include Mohammed Dib, Albert Camus, Kateb Yacine and Ahlam Mosteghanemi while Assia Djebar is widely translated. Among the important novelists of the 1980s were Rachid Mimouni, later vice-president of Amnesty International, and Tahar Djaout, murdered by an Islamist group in 1993 for his secularist views.[76]

In philosophy and the humanities, Jacques Derrida, the father of deconstruction, was born in El Biar in Algiers; Malek Bennabi and Frantz Fanon are noted for their thoughts on decolonization; Augustine of Hippo was born in Tagaste (modern-day Souk Ahras); and Ibn Khaldun, though born in Tunis, wrote the Muqaddima while staying in Algeria. Algerian culture has been strongly influenced by Islam, the main religion. The works of the Sanusi family in pre-colonial times, and of Emir Abdelkader and Sheikh Ben Badis in colonial times, are widely noted. The Latin author Apuleius was born in Madaurus (Mdaourouch), in what later became Algeria.

In painting, Mohammed Khadda[77] and M'Hamed Issiakhem have been notable in recent years.

Landscapes and monuments of Algeria

-

Zighout Youcef Street in Algiers (north)

-

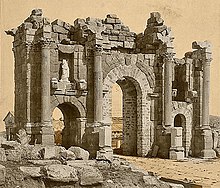

Roman ruins of Timgad(tamugadi) (northeast)

-

1 November Place in the city of Oran (northwest)

-

Tichy's beach in Bejaïa(Bgayet) (north-east)

-

Hanging bridge of the city of Constantine antic(Cirta)

-

El-Kantara in Biskra (south)

-

Mt. Tahat in the Ahaggar Mountains (far south)– highest point in the country (3003m)

UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Algeria

There are several UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Algeria including Al Qal'a of Beni Hammad, the first capital of the Hammadid empire; Tipasa, a Phoenician and later Roman town; and Djémila and Timgad, both Roman ruins; M'Zab Valley, a limestone valley containing a large urbanized oasis; also the Casbah of Algiers is an important citadel. The only natural World Heritage Sites is the Tassili n'Ajjer, a mountain range.

Affiliations

Algeria is a member of the following organizations:

| Organization | Dates |

| since 08-10-1962 | |

| since 16-08-1962 | |

| since 1969 | |

| Organisation of African Unity | since 25-05-1963 |

See also

References

- ^ Constitution of Algeria (1996), Art. 11 [ar]

- ^ Constitution of Algeria (1996), Art. 11 [en]

- ^ Department of Economic and Social Affairs

Population Division (2010). "Population and HIV/AIDS 2010" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); line feed character in|author=at position 42 (help) - ^ a b c d "Algeria". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

- ^ "Distribution of family income – Gini index". The World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2010. Human development index trends" (PDF). The United Nations. Retrieved 2010-11-10.

- ^ Présentation de l’Algérie - ministère des Affaires étrangères

- ^ L'Algérie crée une académie de la langue amazigh

- ^ La mondialisation, une chance pour la francophonie

- ^ Brozolo, Luca G. Radicati di (1990). "Benemar v. Embassy of the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria". American Journal of International Law. 84 (2): 573–577. doi:10.2307/2203476.

- ^ http://www.iusct.org/claims-settlement.pdf

- ^ http://www.mem-algeria.org/legis/Mines_ANNEX-29-04-03.pdf

- ^ http://maghrebeurope.ceth.fr/DAHOR-en.pdf

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Africa: Algeria". CIA World Factbook. Cia.gov. Retrieved 2009-12-07.

- ^ Encarta MSN

- ^ "Population et Démographie". Office National des Statistiques. Retrieved 2010-03-13.

- ^ Michael Brett, Elizabeth Fentress (1997). "Berbers in Antiquity". many29 The Berbers. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-20767-2. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Khaldūn, Ibn (1852). Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique Septentrionale Par Ibn Khaldūn, William MacGuckin Slane (in French). pp. XV. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ^ Khaldūn, Ibn (1852). Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique Septentrionale Par Ibn Khaldūn, William MacGuckin Slane (in French). pp. X. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ^ "Barbary Pirates—Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1911". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ "British Slaves on the Barbary Coast".

- ^ "Jefferson Versus the Muslim Pirates by Christopher Hitchens, City Journal Spring 2007".

- ^ "The mysteries and majesties of the Aeolian Islands".[dead link]

- ^ "Vieste".

- ^ "History of Menorca".

- ^ "When Europeans were slaves: Research suggests white slavery was much more common than previously believed".

- ^ "Watch-towers and fortified towns".[dead link]

- ^ Rees Davies, British Slaves on the Barbary Coast, BBC, 1 July 2003

- ^ Mackie, Erin Skye, Welcome the Outlaw: Pirates, Maroons, and Caribbean Countercultures Cultural Critique – 59, Winter 2005, pp. 24–62

- ^ "Barbary Pirates – Encyclopedia Britannica".

- ^ "Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500–1800". Robert Davis (2004) ISBN 978-1-4039-4551-8

- ^ Alistair Horne, (2006). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962 (New York Review Books Classics). 1755 Broadway, New York, NY 10019: NYRB Classics. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-59017-218-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Template:Fr icon Gallica.bnf.fr, La démographie figurée de l'Algérie, op.cit., p.260 et 261.

- ^ 'France – Republic, Monarchy, and Empire' By Keith Randell

- ^ Alistair Horne, (2006). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962 (New York Review Books Classics). 1755 Broadway, New York, NY 10019: NYRB Classics. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-59017-218-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Country Data". Country-data.com. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ Colonial Memory and Postcolonial Europe, Andrea L. Smith, Indiana University Press, 2006

- ^ "French 'reparation' for Algerians". BBC News. 2007-12-06.

- ^ "Khilafah – An overview of recent events in Algeria". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ Arabic German Consulting www.Arab.de. Retrieved 4 April 2006.

- ^ CNN Wire Staff (24 February 2 011). "Algeria officially lifts state of emergency". CNNWorld. Retrieved 27 February 2 011.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Reuters Staff (24 February 2 011). "Algeria lifts 19-year-old state of emergency". Reuters. Retrieved 27 February 2 011.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ MHerrera.org and Burt, Christopher C. 'Extreme Weather: A Guide and Record Book (W.W. Norton Press, 2007)

- ^ "Democracy Index 2010".

- ^ "Freedom of the Press 2009" (PDF). Freedom House. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ^ "BBC NEWS". News.bbc.co.uk. November 12, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

{{cite news}}: Text "Africa" ignored (help); Text "Algeria deputies scrap term limit" ignored (help) - ^ a b Hackett, James (ed.) (5 February 2008). The Military Balance 2008. International Institute for Strategic Studies. Europa. ISBN 978-1-85743-461-3. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Venezuela's Chavez to finalise Russian submarines deal". Breitbart. 2007-06-14. Retrieved 2008-07-16.

- ^ "Algeria cancels weapons deal over Israeli parts". Infoprod.co.il. Retrieved 2010-04-23. [dead link]

- ^ ArabicNews.com, Bin Ali calls for reactivating Arab Maghreb Union, Tunisia-Maghreb, Politics, 19 February 1999. Retrieved 4 April 2006.

- ^ Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ Algeria Country Analysis Brief, EIA, March 2005. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- ^ [1], MFW4A, Algeria Financial Sector Profile

- ^ "Brtsis, brief on Russian defence, trade, security and energy". Brtsis.com. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ "Russia agrees Algeria arms deal, writes off debt". Reuters. 11 March 2006. [dead link]

- ^ Template:Fr icon "La Russie efface la dette algérienne". Radio France International. 10 March 2006.

- ^ "CIA factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ John Douglas Ruedy (2005). "Modern Algeria: the origins and development of a nation". Indiana University Press. p.22. ISBN 0253217822

- ^ Raimondo Cagiano De Azevedo (1994). "Migration and development co-operation.". Council of Europe. p.25. ISBN 9287126119

- ^ Slackman, Michael (May 26, 2007). "A Quiet Revolution in Algeria: Gains by Women – New York Times". Nytimes.com. doi:Algeria. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

{{cite news}}: Check|doi=value (help) - ^ U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. "World Refugee Survey 2008." Available Online at Refugees.org, pp.34

- ^ "Home: Only 46,000 people benefit from humanitarian aid in Tindouf camps, says former polisario leader". Map.ma. Retrieved 2010-11-27.

- ^ Buckley, Cara (2008-06-04). "Western Sahara's Conflict Traps Refugees in Limbo". The New York Times.

- ^ "Western Sahara: Lack of donor funds threatens humanitarian projects". IRIN Africa. September 5, 2007.

- ^ "Chinese migrants in Algiers clash". BBC News. August 4, 2009.

- ^ Leclerc, Jacques (2009-04-05). "Algérie: Situation géographique et démolinguistique". L'aménagement linguistique dans le monde. Université Laval. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ^ a b Template:Fr icon – TLFQ.ulaval.ca, Jacques Leclerc, L’aménagement linguistique dans le monde. CIRAL (Centre international de recherche en aménagement linguistique)

- ^ Template:Fr icon – « Loi n° 02-03 portant révision constitutionnelle », adopted on 10 April 2002.

- ^ "Ibadis and Kharijis". Angelfire.com. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ "Top Chrétien". Topchretien.com. Retrieved 2010-04-23.[dead link]

- ^ "Vodeo TV". Vodeo TV. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ "Over en million Jesus-troende i Algerie" (in Norwegian). Troens Bevis - Verdens Evangelisering. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ "U.S. Department of State". State.gov. 2007-04-11. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2009 – Proportion of international migrant stocks residing in countries with very high levels of human development (%)". Hdrstats.undp.org. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ^ "Algeria – Education". Nationsencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ Tahar Djaout French Publishers' Agency and France Edition, Inc. Retrieved 4 April 2006.

- ^ Mohammed Khadda official site. Retrieved 4 April 2006.

Bibliography

- Ageron, Charles-Robert (1991). Modern Algeria. A History from 1830 to the Present. Translated from French and edited by Michael Brett. London: Hurst. ISBN 978-0-86543-266-6.

- Aghrout, Ahmed and Bougherira, Redha M. (2004). Algeria in Transition: Reforms and Development Prospects. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-34848-5

- Bennoune, Mahfoud (1988). The Making of Contemporary Algeria: Colonial Upheavals and Post-Independence Development, 1830–1987. Cambridge U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30150-3.

- Fanon, Frantz (1966). The Wretched of the Earth. Grove Press. ASIN B0007FW4AW, ISBN 978-0-8021-4132-3 (2005 paperback).

- Horne, Alistair (1977). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962. Viking Adult. ISBN 978-0-670-61964-1, ISBN 978-1-59017-218-6 (2006 reprint)

- Laouisset, Djamel (2009). A Retrospective Study of the Algerian Iron and Steel Industry. New York: Nova Publishers. ISBN 0902548267

- Roberts, Hugh (2003). The Battlefield: Algeria, 1988–2002. Studies in a Broken Polity. London: Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-684-1.

- Ruedy, John (1992). Modern Algeria: The Origins and Development of a Nation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34998-9.

- Stora, Benjamin (2001). Algeria, 1830–2000. A Short History. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3715-1.

External links

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- Algeria

- African countries

- Arabic-speaking countries

- Countries of the Mediterranean Sea

- French-speaking countries

- G15 nations

- Member states of the African Union

- Member states of the Arab League

- Member states of OPEC

- Member states of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference

- Member states of the Union for the Mediterranean

- Republics

- Requests for audio pronunciation (Arabic)

- Requests for audio pronunciation (Berber)

- States and territories established in 1962