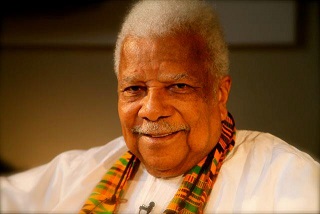

Ali Mazrui

Ali Mazrui | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 24 February 1933 |

| Died | 12 October 2014 (aged 81) Vestal, New York, United States |

| Resting place | Mazrui Graveyard, Mombasa 4°03′43″S 39°40′44″E / 4.061843°S 39.678912°E |

| Nationality | Kenyan |

| Alma mater | Manchester University (BA) Columbia University (MA) Nuffield College, Oxford (PhD) |

| Occupation(s) | Academic and political author |

| Years active | 1966–2014 |

| Known for | Coining the term "black orientalism" |

| Television | The Africans: A Triple Heritage |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 5 |

| Awards | Top 100 Public Intellectuals (2005) |

| Website | www |

Ali Al'amin Mazrui (24 February 1933 – 12 October 2014), was a Kenyan-born American academic, professor, and political writer on African and Islamic studies, and North-South relations. He was born in Mombasa, Kenya. His positions included Director of the Institute of Global Cultural Studies at Binghamton University in Binghamton, New York, and Director of the Center for Afro-American and African Studies at the University of Michigan.[1][2] He produced the 1980s television documentary series The Africans: A Triple Heritage.

Early life[edit]

Mazrui was born on 24 February 1933 in Mombasa, Kenya Colony.[3] He was the son of Al-Amin Bin Ali Mazrui, the Chief Islamic Judge in Kadhi courts of Kenya Colony. His father was also a scholar and author, and one of his books has been translated into English by Hamza Yusuf as The Content of Character (2004), to which Ali supplied a foreword. The Mazrui family was a historically wealthy and important family in Kenya, having previously been the rulers of Mombasa. Ali's father was the Chief Kadhi of Kenya, the highest authority on Islamic law. Mazrui credited his father for instilling in him the urge for intellectual debate, as his father not only participated in court proceedings but also was a renowned pamphleteer and public debater. Mazrui would, from a young age, accompany his father to court and listen in on his political and moral debates.[4] Mazrui initially intended to follow the path of his father as an Islamist and pursue his study in Al-Azhar University in Egypt.[5] Due to poor performance in the Cambridge School Certificate examination in 1949, Mazrui was refused entry to Makerere College (now Makerere University), the only tertiary education institute in East Africa at that time. He then worked in the Mombasa Institute of Muslim Education (now Technical University of Mombasa).[5]

Education[edit]

Mazrui attended primary school in Mombasa, where he recalled having learned English specifically to participate in formal debates, before he turned the talent to writing. Journalism, according to Mazrui, was the first step he took down the academic road. In addition to English, Mazrui also spoke Swahili and Arabic.[6] After getting a Kenyan Government scholarship,[5] Mazrui furthered his study and obtained his B.A. degree with Distinction from Manchester University in Great Britain in 1960, his M.A. from Columbia University in New York in 1961, and his doctorate (DPhil) from Oxford University (Nuffield College) in 1966.[7] He was influenced by Kwame Nkrumah's ideas of pan-Africanism and consciencism, which formed the backbone of his discussion on "Africa's triple heritage" (Africanity, Islam and Christianity).[5]

Academic career[edit]

Mazrui began his academic career at Makerere University in Uganda, where he had dreamed of attending since he was a child.[4] At Makerere, Mazrui served as a professor of political science, and began drawing his international acclaim. Mazrui felt that his years at Makerere were some of the most important and productive of his life. He told his biographer that 1967, when he published three books, was the year that he had made his declaration to the academic world "that I planned to be prolific – for better or for worse!" During his time at Makerere, Mazrui also directed the World Order Models Project in the Department of Political Science, a project which brought together political scientists from across the world to discuss what an international route to lasting peace might be.[8]

Mazrui reflected that he felt forced to leave the University of Makerere.[9] His departure was likely the result of his desire to remain a neutral academic in the face of pressures to attach his growing prestige as a political thinker to one of the regional factions. His first solicitation was from John Okello, the leader of the Zanzibar Revolution, who came to Mazrui's house in 1968 to urge Mazrui to join his cause. Okello originally tried to convince Mazrui to become an advisor to him and then simply tried to enlist Mazrui's assistance in writing a constitution for Zanzibar. Mazrui told Okello that, while he was inclined to sympathize with the cause, it would be a violation of the moral duty of a professor and an academic to join with a political agenda. This incident shows the level of international prestige that Mazrui had already accumulated. Okello had sought him out specifically because he knew and valued Ali's reputation as an anti-imperialist intellectual.[10]

Mazrui was later approached by Idi Amin who was the president of Uganda at the end of Mazrui's time at Makerere. Amin, according to Mazrui, wanted Mazrui to become his special adviser. Mazrui declined this invitation, for fear that it would be unsafe, and by doing so lost his political standing in Uganda. This would be what Mazrui ultimately felt forced him to leave the University of Makerere.[11] Mazrui often said that he would like to return to Uganda, but cited his strained relationship with the Ugandan government, as well as the unfriendliness of the Ugandan people towards a Kenyan political scientist as the factors keeping him away.[12]

In 1974, Mazrui was hired as a professor of political science at the University of Michigan. During his time at Michigan, Mazrui also held a professorship at the University of Jos in Nigeria. He held that spending time teaching and being part of the discourse in Africa was important to not losing his understanding of the African perspective. From 1978 until 1981 Mazrui served as the Director of the Center for Afro-American and African Studies (CAAS) at the University of Michigan. While he had a relatively quiet tenure in the chair, his presence there was important for a couple reasons. First, it was a central view of Mazrui's that the African American and the African connection had to be strengthened. He believed the way to better Africa was to educate African Americans in global politics and to strengthen their connection with Africa, all things that could be under the purview of CAAS. However he also seemed to doubt the ability of a program like CAAS to accomplish anything. During his earlier years at U of M he criticized such programs saying that, in response to black activism, "some universities just established a black-studies program with a kind of political cynicism which I found rather difficult to admire, to say the very least."[13]

Mazrui taught at the University of Michigan until 1989, when he took a two-year leave of absence to accept the Albert Schweitzer professorship at SUNY Binghamton. Mazrui's departure from U of M was no less eventful than his departure from Makerere. Mazrui announced his resignation from the University of Michigan on 29 May 1991. Leading up to this point, there had been a highly publicized bidding war between U of M and SUNY. Reportedly, SUNY offered Mazrui a $500,000 package which included a $105,000 salary (as compared to his $71,500 salary at U of M) as well as the funds for three professors of Mazrui's choosing, three graduate assistants, a secretary, and travel expenses.[14] The University of Michigan reportedly matched this offer, but Mazrui decided it was too little too late. He stated that he was unconvinced by U of M's commitment to the study of political science in the third world. Both governor Mario Cuomo from New York and Governor James Blanchard from Michigan gave Mazrui personal calls to convince him to choose the university in their states. The whole affair sparked questions about the commodification as well as the celebrity of university professors.[15]

His departure also caused a conversation about racial diversity at the University of Michigan; a conversation he had not been a huge part of for the fifteen years while he was on the U of M campus. In spite of the University of Michigan's efforts to retain Ali Mazrui, James Duderstadt, the president of the university at the time, came under heavy fire for not being proactive enough in the retention of an esteemed Black professor. Mazrui had been hired in 1974, while the university was under heavy criticism, especially from the second Black Action Movement, for not keeping its promises for diversity in the student body and among the faculty. In contrast, Duderstadt argued that, by 1989, the University was doing a much better job of diversifying. They had added 45 minority faculty that year, 13 more than the year before and the College of Literature, Science and the Arts had seen "skyrocketing minority recruitment."[16] Even still there was a worry that the university was focusing only on recruiting minorities, and not on making them stick around.[17][18][19]

Appointments[edit]

In addition to his appointments as the Albert Schweitzer Professor in the Humanities, Professor in Political Science, African Studies, Philosophy, Interpretation and Culture and the Director of the Institute of Global Cultural Studies (IGCS), Mazrui also held three concurrent faculty appointments as Albert Luthuli Professor-at-Large in the Humanities and Development Studies at the University of Jos in Nigeria, Andrew D. White Professor-at-Large Emeritus and senior scholar in Africana Studies at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York and chancellor of the Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Nairobi, Kenya. In 1999, Mazrui retired as the inaugural Walter Rodney Professor at the University of Guyana, Georgetown, Guyana. Mazrui has also been a visiting scholar at Stanford University, The University of Chicago, Colgate University, McGill University, National University of Singapore, Oxford University, Harvard University, Bridgewater State College, Ohio State University, and at other institutions in Cairo, Australia, Leeds, Nairobi, Teheran, Denver, London, Baghdad, and Sussex, among others. In 2005, Ali Mazrui was selected as the 73rd topmost intellectual person in the world on the list of Top 100 Public Intellectuals by Prospect Magazine (UK) and Foreign Policy (United States).[20]

Central views[edit]

Africa's triple heritage[edit]

The inspiration for his documentary series The Africans: A Triple Heritage was Ali's view that much of modern Africa could be described by its three main influences:[citation needed]

- the colonial and imperialist legacy of the West,

- the spiritual and cultural influence of Islam spreading from the east, and

- Africa's own indigenous legacy.

The paradoxes of Africa[edit]

Mazrui believed there were six paradoxes that are central to understanding Africa:

- Africa was the birthplace of humankind, but it is the last continent (besides Antarctica) to be made habitable in a modern sense.

- Although Africans have not been the most abused group of people in modern history, they have been the most humiliated.

- Africa is the most different from the West culturally, but is westernizing very quickly.

- Africa possesses extreme natural wealth, but its people are very poor.

- Africa is huge, yet very fragmented.

- Africa is geographically central, but politically marginal.[4]

The problem of Africa's dependency[edit]

Mazrui argued that, as long as Africa remained dependent on the developed world, no relationship between the developed world and Africa would be beneficial to Africa. In the face of détente between the US and the USSR, Mazrui was quoted as saying: "When elephants fight, it is the grass that suffers. When elephants make love, however, it is also the grass that suffers."[21]

Africa's greatest resource[edit]

Mazrui believed the greatest resource that Africa possessed was the African people. In particular, he pointed to African Americans, arguing that they must remember their African heritage and find a way to exert their influence over U.S. foreign policy if Africa ever hopes to climb out of its marginal position. Ali explained to a friend, Dr Kipyego Cheluget, that his joint professorship at Michigan and Jos was his attempt to be a part of such a connection.[22]

Professional organizations[edit]

In addition to his academic appointments, Mazrui also served as president of the African Studies Association (USA) and as vice-president of the International Political Science Association and has also served as special advisor to the World Bank. He has also served on the board of the American Muslim Council, Washington, D.C.

Works[edit]

Mazrui's research interests included African politics, international political culture, political Islam and North-South relations. He is author or co-author of more than twenty books. Mazrui has also published hundreds of articles in major scholastic journals and for public media. He has also served on the editorial boards of more than twenty international scholarly journals. Mazrui was widely consulted by heads of states and governments, international media and research institutions for political strategies and alternative thoughts.

He first rose to prominence as a critic of some of the accepted orthodoxies of African intellectuals in the 1960s and 1970s. He was critical of African socialism and all strains of Marxism. He argued that communism was a Western import just as unsuited for the African condition as the earlier colonial attempts to install European type governments. He argued that a revised liberalism could help the continent and described himself as a proponent of a unique ideology of African liberalism.

At the same time he was a prominent critic of the current world order. He believed the current capitalist system was deeply exploitative of Africa, and that the West rarely if ever lived up to their liberal ideals and could be described as global apartheid. He has opposed Western interventions in the developing world, such as the Iraq War. He has also long been opposed to many of the policies of Israel, being one of the first to try to link the treatment of Palestinians with South Africa's apartheid.[23]

Especially in recent years, Mazrui became a well known commentator on Islam and Islamism. While rejecting violence and terrorism Mazrui has praised some of the anti-imperialist sentiment that plays an important role in modern Islamic fundamentalism. He has also argued, controversially, that sharia law is not incompatible with democracy.[24]

In addition to his written work, Mazrui was also the creator of the television series The Africans: A Triple Heritage, which was jointly produced by the BBC and the Public Broadcasting Service (WETA, Washington) in association with the Nigerian Television Authority, and funded by the Annenberg/CPB Project. A book by the same title was jointly published by BBC Publications and Little, Brown and Company in 1986.

Controversy[edit]

The Africans was a controversial series for some. In the UK, where it aired on the BBC, it slid more or less under the radar. In the United States, however, where it aired on some PBS channels, The Africans drew a great amount of scrutiny for being allegedly anti-western. According to critics, The Africans blames too many of Africa's problems on the negative influences of Europe and America, and the loudest criticisms came for the portrayal of Muammar Gaddafi as a virtuous leader.

The loudest critic of the documentary series was Lynne Cheney, who was at the time the chairperson of the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). The endowment had put $600,000 toward the funding of The Africans and Cheney felt that Mazrui had not held to the conditions on which the endowment had granted the funding. Cheney said that she was promised a variety of interviews presenting different sides of the story, and was outraged when there were no such interviews in the show. Cheney demanded that the NEH name and logo be removed from the credits. She also had the words "A Commentary" added to the American version of the series, alongside Mazrui's credits.

In defense of the series and its alleged bias, Mazrui made the statement: "I was invited by PBS and the BBC to tell the American and British people about the African people, a view from the inside. I am surprised, then, that people are disappointed not to get an American view. An effort was made to be fair but not to sound attractive to Americans." Ward Chamberlain, the president of series co-producer WETA, also stepped in to publicly defend the series and Mazrui by saying that, in a fair telling of history, the western world should not be expected to come out looking good from the African perspective.[11][25][26]

Other academic controversies[edit]

His experience as a controversial figure was different in the two continents. While he was surrounded by controversy at U of M (he has been accused of being anti-Semitic, anti-American, and generally radical) he wrote to his African colleagues saying that the debate had remained remarkably civil and academic.[27] On the other hand, in Jos, things got so heated that the university faculty once put out a flyer threatening to punish anti-Mazrui libel "in the pugilist style". Ironically, the libeler was a socialist accusing Mazrui of being overly imperialist for participating in western dialogues.[28]

Israel-Palestine[edit]

Probably the most fire Mazrui came under during his tenure at the University of Michigan was in response to his views on the Israel-Palestine conflict. Mazrui was an outspoken supporter of Palestine and, more than that, an outspoken critic of the state of Israel. Mazrui made the argument that Israel and the Zionist movement behaved in an imperialist fashion and that they used their biblical beliefs and the events of the holocaust for political gain. He went so far as to call the Israeli government "fascist" in its behavior.[29] This sparked controversy.[30] The large Jewish population at the University of Michigan was highly critical of these remarks, accusing him of anti-Semitism. In the campus newspaper, The Michigan Daily, there was a prolonged back-and-forth in 1988. One student wrote: "Mazrui is completely ignorant regarding Jewish faith and history. To compare Israel to Nazi Germany is the ultimate racial slur … To digress from politics to anti-Semitic tones only fuels the fire of hatred."[29]

On the other hand, in a joint letter to the Michigan Daily, members of the Palestine Solidarity Committee wrote: "A recent letter has accused Dr. Ali Mazrui and his supporters of anti-Semitism… we categorically reject this vicious slander."[31] Mazrui, in his own defense, stated unequivocally that he was anti-Zionist, but that that was a fundamentally different thing from anti-Semitism. He admitted to having problems with the Israeli government and the Zionist movement, but said that he held these views independent of any views about the Jewish people as an ethnicity.[32]

Nuclear proliferation[edit]

Throughout his career Mazrui held the controversial position that the only way to prevent a nuclear holocaust was to arm the "Third World" (Africa in particular) with nuclear weapons. This was a view spotlighted in The Africans.[11] Speaking largely with a mind to cold war international politics, Mazrui argued that the world needed more than two sides holding nuclear arms. By virtue of the continent's central location and relative non-alignment, he argued that Africa would be the perfect keeper of the peace between the East and the West. Furthermore, as long as the third world did not have nuclear capabilities, it would continue to be marginalized on the global stage.[33] This view encountered heavy criticism from those who believed that the more countries with nuclear capabilities, and the more unstable those countries are politically, the greater the risk of some leader or military organization launching nuclear missiles.[34]

Positions held[edit]

- Professor of Political Science, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A.

- Director, Center for Afro-American and African Studies, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A.

- Director, Institute of Global Cultural Studies, Binghamton University, State University of New York, Binghamton, New York, U.S.A.

- Albert Schweitzer Professor in the Humanities, Binghamton University, State University of New York, Binghamton, New York, U.S.A.

- Professor of Political Science, African Studies and Philosophy, Interpretation and Culture, Binghamton University, State University of New York, Binghamton, New York, U.S.A.

- Chancellor, Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, Nairobi, Kenya

- Albert Luthuli Professor-at-Large, University of Jos, Jos, Nigeria

- Senior Scholar in Africana Studies and Andrew D. White Professor-at-Large Emeritus, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, U.S.A.

- 2008–2009 M. Thelma McAndless Distinguished scholar, Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, MI, U.S.A.

- President, Association of Muslim Social Scientists of North America, Washington, D.C., U.S.A.

Membership of organizations (1980–1995)[edit]

- Fellow, African Academy of Sciences

- Member, Pan-African Advisory Council to UNICEF (The United Nations' Children's Fund)

- Vice-President, World Congress of Black Intellectuals

- Member, United Nations Commission on Transnational Corporations

- Distinguished Visiting Professor, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, U.S.A. (Spring)

- Member, Bank's Council of African Advisors, The World Bank (Washington, D.C.)

- Vice-President, International African Institute, London, England

- Member of the Advisory Board of Directors of the Detroit Chapter, Africare

Media[edit]

- Featured in 2010 film Motherland, directed by Owen Alik Shahadah, featuring key academics from around the continent of Africa. Ali Mazrui in Motherland film

- Main African consultant and on-screen respondent, "A History Denied" in the television series on Lost Civilizations (NBC and Time-Life, 1996), U.S.A.

- "The Bondage of Boundaries: Towards Redefining Africa", in the 150th anniversary issue of The Economist (London) (September 1993), Vol. 328, No. 7828.

- Author and narrator, The Africans: A Triple Heritage, BBC and PBS television series in cooperation with Nigerian Television Authority, 1986, funded by the Annenberg/CPB Project.

- Author and broadcaster, The African Condition, BBC Reith Radio Lectures, 1979, with book of the same title (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980)

- Advisor to the award-winning, PBS-broadcast documentary Muhammad: Legacy of a Prophet (2002), produced by Unity Productions Foundation.

Mazrui was a regular contributor to newspapers in Kenya, Uganda, and South Africa, most notably the Daily Nation (Nairobi), The Standard (Nairobi), the Daily Monitor (Kampala), and the City Press (Johannesburg).

Awards[edit]

- Millennium Tribute for Outstanding Scholarship, House of Lords, Parliament Buildings, London, June 2000

- Special Award from the Association of Muslim Social Scientists (United Kingdom), honoring Mazrui for his contribution to the social sciences and Islamic studies, June 2000

- Honorary Doctorate of Letters from various universities for fields which include Divinity, Humane Letters, and the Sciences of Development

- Icon of the Twentieth Century, elected by Lincoln University, Pennsylvania, U.S.A., 1998

- Appointed Walter Rodney Professor, University of Guyana, Georgetown, Guyana, 1998

- Icon of the Twentieth Century Award, Lincoln University, Lincoln University, Pennsylvania, 1998

- DuBois-Garvey Award for Pan-African Unity, Morgan State University, Baltimore, Maryland, 1998

- Appointed Ibn-Khaldun Professor-at-Large, Graduate School of Islamic and Social Sciences, Leesburg, Virginia, 1997–2001

- Distinguished Faculty Achievement Award, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. 1988

- Appointed Distinguished Andrew D. White Professor-at-Large, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, U.S.A. (1986–1992)

- Rumi Forum Extraordinary Commitment to Education Award, 2013

Mazrui was ranked among the world's top 100 public intellectuals by readers of Prospect Magazine (UK) Foreign Policy Magazine (Washington, D.C.) (see The 2005 Global Intellectuals Poll).

Death[edit]

According to press reports, Mazrui had not been feeling well for several months prior to his death.[35] He died of natural causes at his home in Vestal in New York on Sunday, 12 October 2014.[36][37] His body was repatriated to his hometown Mombasa, where it arrived early morning on Sunday 19 October. It was taken to the family home where it was washed as per Islamic custom.[38] The funeral prayer was held at the Mbaruk Mosque in Old Town and he was laid to rest at the family's Mazrui Graveyard opposite Fort Jesus. His burial was attended by Cabinet Secretary Najib Balala, Majority Leader Aden Bare Duale, Governor Hassan Ali Joho; and Senators Hassan Omar and Abu Chiaba.[39]

Publications[edit]

- 2008: Islam in Africa's Experience [editor: Ali Mazrui, Patrick Dikirr, Robert Ostergard Jr., Michael Toler and Paul Macharia] (New Delhi: Sterling Paperbacks).

- 2008: Euro-Jews and Afro-Arabs: The Great Semitic Divergence in History [editor: Seifudein Adem], (Washington DC: University of America Press).

- 2008: The Politics of War and Culture of Violence [editor: Seifudein Adem and Abdul Bemath] (Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press).

- 2008: Globalization and Civilization: Are they Forces in Conflict? [editor: Ali Mazrui, Patrick Dikirr, Shalahudin Kafrawi], (New York: Global Academic Publications).

- 2006: A Tale of two Africas: Nigeria and South Africa as contrasting Visions [editor: James N. Karioki] (London: Adonis & Abbey Publishers).

- 2006: Islam: Between Globalization & Counter-Terrorism [editors: Shalahudin Kafrawi, Alamin M. Mazrui and Ruzima Sebuharara] (Trenton, NJ and Asmara, Eritrea: Africa World Press).

- 2004: The African Predicament and the American Experience: a Tale of two Edens (Westport, CT and London: Praeger).

- 2004: Almin M. Mazrui and Willy M. Mutunga (eds). Race, Gender, and Culture Conflict: Mazrui and His Critics (Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press).

- 2003: Almin M. Mazrui and Willy M. Mutunga (eds). Governance and Leadership:Debating the African Condition (Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press).

- 2002: Black Reparations in the era of Globalization [with Alamin Mazrui] (Binghamton: The Institute of Global Cultural Studies).

- 2002: The Titan of Tanzania: Julius K. Nyerere's Legacy (Binghamton: The Institute of Global Cultural Studies).

- 2002: Africa and other Civilizations: Conquest and Counter-Conquest, The Collected Essays of Ali A. Mazrui, Vol. 2 [series editor: Toyin Falola; editors: Ricardo Rene Laremont & Fouad Kalouche] (Trenton, NJ and Asmara, Eritrea: Africa World Press)

- 2002: Africanity Redefined, The Collected Essays of Ali A. Mazrui, Vol. 1 [Series Editor: Toyin Falola; Editors: Ricardo Rene Laremont & Tracia Leacock Seghatolislami] (Trenton, NJ, and Asmara, Eritrea: Africa World Press).

- 1999: Political Culture of Language: Swahili, Society and the State [with Alamin M. Mazrui] (Binghamton: The Institute of Global Cultural Studies).

- 1999: The African Diaspora: African Origins and New World Identities [co-editors Isidore Okpewho and Carole Boyce Davies] (Bloomington: Indiana University Press).

- 1998: The Power of Babel: Language and Governance in the African Experience [with Alamin M. Mazrui] (Oxford and Chicago: James Currey and University of Chicago Press).

- 1995: Swahili, State and Society: The Political Economy of an African Language [with Alamin M. Mazrui] (Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers).

- 1993: Africa since 1935: Vol. VIII of UNESCO General History of Africa [editor; asst. ed. C. Wondji] (London: Heinemann and Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

- 1990: Cultural Forces in World Politics (London and Portsmouth, N.H: James Currey and Heinemann).

- 1986: The Africans: A Triple Heritage (New York: Little Brown and Co., and London: BBC).

- 1986: The Africans: A Reader Senior Editor [with T.K. Levine] (New York: Praeger).

- 1984: Nationalism and New States in Africa: From about 1935 to the Present [with Michael Tidy] (Heinemann Educational Books, London).

- 1980: The African Condition: A Political Diagnosis [The Reith Lectures] (London: Heinemann Educational Books. and New York: Cambridge University Press).

- 1978: The Warrior Tradition in Modern Africa [editor] (The Hague and Leiden, The Netherlands: E.J. Brill Publishers).

- 1978: Political Values and the Educated Class in Africa (London: Heinemann Educational Books and Berkeley, CA: University of California Press).

- 1977: State of the Globe Report, 1977 (edited and co-authored for World Order Models Project)

- 1977: Africa's International Relations: The Diplomacy of Dependency and Change (London: Heinemann Educational Books and Boulder: Westview Press).

- 1976: A World Federation of Cultures: An African Perspective (New York: Free Press).

- 1975: Soldiers and Kinsmen in Uganda: The Making of a Military Ethnocracy (Beverly Hills: Sage Publication and London).

- 1975: The Political Sociology of the English Language: An African Perspective (The Hague: Mouton Co.).

- 1973: World Culture and the Black Experience (Seattle: University of Washington Press).

- 1973: Africa in World Affairs: The Next Thirty Years [co-edited with Hasu Patel] (New York and London: The Third Press).

- 1971: The Trial of Christopher Okigbo [novel] (London: Heinemann Educational Books and New York: The Third Press).

- 1971: Cultural Engineering and Nation-Building in East Africa (Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press).

- 1970: Protest and Power in Black Africa [co-edited with Robert I. Rotberg] (New York: Oxford University Press).

- 1969: Violence and Thought: Essays on Social Tentions in Africa (London and Harlow: Longman).

- 1967: Towards a Pax Africana: A Study of Ideology and Ambition (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, and University of Chicago Press).

- 1967: On Heroes and Uhuru-Worship: Essays on Independent Africa (London: Longman).

- 1967: The Anglo-African Commonwealth: Political Friction and Cultural Fusion (Oxford: Pergamon Press).

References[edit]

- ^ Daily Nation (13 October 2014). "Professor Ali Mazrui Dies in US". Daily Monitor (Kampala). Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ Ian (13 October 2014). "Who Was Professor Ali Mazrui?". The Independent (Uganda). Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ Cyrus Ombati (13 October 2014). "Professor Ali Mazrui is dead".

- ^ a b c "Ali Mazrui: A Confluence of Three Cultures" from April/May 1982 Research News, Ali Mazrui Papers, Box 9, Bentley Library

- ^ "Africana Studies and Research Center | Africana Studies & Research Center Cornell Arts & Sciences". africana.cornell.edu.

- ^ Nabiruma, Diana (19 August 2009). "Ali Mazrui – In His Own Words". The Observer (Uganda). Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ Correspondence with Hasu Patel, Conference Organiser, of conference on Africa in World Affairs in the Next Thirty Years, December 1969. Ali Mazrui Papers, Box 7, Bentley Library.

- ^ Letter from Ali Mazrui to Merrick Posnansky. Ali Mazrui Papers, Box 7, Bentley Library.

- ^ Report to the Principal, Makerere University, 6 November 1968. Ali Mazrui Papers, Box 8, Bentley Library.

- ^ a b c Mitgang, Herbert (5 October 1986). "Looking at Africa Through an African's Eyes". The New York Times.

- ^ Ali Mazrui correspondence with Ann Gourlay, Ali Mazrui Papers, Box 7, Bentley Library.

- ^ Interview with Ali Mazrui, "Race Relations in the United States". Ali Mazrui Papers, Box 7, Bentley Library.

- ^ Julie Wiernik, "African expert quits U-M for SUNY post", The Ann Arbor News, Thurs, 30 May 1991. News and Information Services Faculty and Staff Files, Box 85, Bentley Library.

- ^ Connie Leslie, "Let's Buy a Physicist or Two", Newsweek, 12 February 1990. News and Information Services Faculty and Staff Files, Box 85, Bentley Library.

- ^ "LS&A’s skyrocketing minority recruitment", Ann Arbor Observer, September 1989. News and Information Services Faculty and Staff Files, Box 85, Bentley Library.

- ^ Taraneh Shafii, 'U' adds 45 new minority to faculty, Michigan Daily, Monday 2 October 1989. News and Information Services Faculty and Staff Files, Box 85, Bentley Library.

- ^ Joe Stroud, "U-M can make fitting pledge to pluralism", Detroit News, 5/14/89. News and Information Services Faculty and Staff Files, Box 85, Bentley Library.

- ^ Karen Grassmuck, "U-M accused of dawdling on diversity", The Ann Arbor News, Friday 15 September 1989. News and Information Services Faculty and Staff Files, Box 85, Bentley Library.

- ^ Jowi, Frenny (13 October 2014). "Kenya's Ali Mazrui: Death of A Towering Intellectual". BBC News. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ^ Deborah Gilbert, News and Information Services, U/K Supplement 5/22/88. News and Information Services Faculty and Staff Files, Box 85, Bentley Library.

- ^ Letter from Mazrui to Mr. Kipyego Cheluget, 19 June 1984. Ali Mazrui Papers, Box 9, Bentley Library.

- ^ Hatem Bazian (18 October 2014). "An intellectual giant: Ali Mazrui (1933–2014)". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ^ Skipjen2865 (22 October 2014). "Biographies: A00256 - Ali Mazrui, Controversial Scholar of Africa". Biographies. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Deborah Gilbert, The University Record, 13 October 1986. News and Information Services Faculty and Staff Files, Box 85, Bentley Library.

- ^ Irvin Molotsky, "U.S. Aide Assails TV Series on Africa", The New York Times, 5 September 1986. News and Information Services Faculty and Staff Files, Box 85, Bentley Library.

- ^ Ali Mazrui letter to George Mendenhall, 4 December 1984. Ali Mazrui Papers, Box 9, Bentley Library

- ^ Pamphlet by Raphaels Donjur, Ali Mazrui Papers, Box 9, Bentley Library.

- ^ a b Marc Brennan, Michigan Daily, Opinion Piece. 26 September 1988. News and Information Services Faculty and Staff Files, Box 85, Bentley Library.

- ^ Mark Weisbrot, The Michigan Daily, 23 September 1988. News and Information Services Faculty and Staff Files, Box 85, Bentley Library.

- ^ "Judaism is not Zionism", Dallas Kenny, Chuck Abookire, Nuha Khoury, et al. (as members of the Palestine Solidarity Committee), letter to the Daily, 18 October 1988. News and Information Services Faculty and Staff Files, Box 85, Bentley Library.

- ^ Victoria Bauer, "A struggle for common ground", Michigan Daily Weekend Magazine, 17 March 1989. News and Information Services Faculty and Staff Files, Box 85, Bentley Library.

- ^ Mazrui, Ali (12 December 1979). "Lecture 6: In Search of Pax Africana" (PDF). Reith Lectures 1979: The African Condition.

- ^ Oyvind Osterun, Article in Dagbladet, 4 August 1981. Ali Mazrui Papers, Box 9, Bentley Library.

- ^ Mghenyi, Charles (13 October 2014). "Kenya: Ali Mazrui To Be Buried at Monumental Family Graveyard Opposite Fort Jesus". The Star (Kenya) via AllAfrica.com. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "Family Obituary of Ali Mazrui" (PDF). Cornell Africana Studies and Research Center. October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ^ Douglas Martin, "Ali Mazrui, Scholar of Africa Who Divided U.S. Audiences, Dies at 81", The New York Times, 20 October 2014.

- ^ Mghenyi, Charles (17 October 2014). "Prof Mazrui to be buried this Sunday". The Star (Kenya). Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ "Renowned scholar Mazrui laid to rest in Mombasa". Capital News. 19 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

Further reading[edit]

- Adam, Hussein M. "Kwame Nkrumah: Leninist Czar or Leninist Garvey?" in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. xi–xvii.

- Annan, Kofi, "The Global African", in Parviz Morewedge, The Scholar Between Thought and Experience (Binghamton, NY: Institute of Global Cultural Studies, 2001), pp. 339–340.

- Anwar, Etin, "Mazrui and Gender: On the Question of Methodology", in The Mazruiana Collection Revisited: Ali A. Mazrui debating the African condition. An annotated and select thematic bibliography 1962–2003, compiled by Abdul Samed Bemath (Pretoria, South Africa: Africa Institute of South Africa and New Dawn Press Group, 2005), pp. 363–377.

- Anyaoku, Emeka, "Foreword", in The Mazruiana Collection Revisited: Ali A. Mazrui debating the African condition. An annotated and select thematic bibliography 1962–2003, compiled by Abdul Samed Bemath (Pretoria, South Africa: Africa Institute of South Africa and New Dawn Press Group, 2005), pp. ix.

- Avari, Burjor, "Recollections of Ali Mazrui as an Undergraduate", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. 291–296.

- Assensoh, A B., and Alex-Assensoh, Y. M. "The Mazruiana Collection Revisited: An Introduction", in The Mazruiana Collection Revisited: Ali A. Mazrui debating the African condition. An annotated and select thematic bibliography 1962–2003, compiled by Abdul Samed Bemath (Pretoria, South Africa: Africa Institute of South Africa and New Dawn Press Group, 2005), pp. xxiii–xxviii.

- Ayele, Negussay. "Mazruiana on Conflict and Violence in Africa", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. 105–119.

- Bakari, Mohamed. "Ali Mazrui’s Political Sociology of Language", in Robert Ostergard, Ricardo Rene Laremont and Fouad Kalouche (eds), Power, Politics, and the African Condition. Collected Essays of Ali A. Mazrui. Vol. 3. Trenton, NJ, and Asmara, Eritrea: Africa World Press, 2004, pp. 411–429.

- Bemath, Abdul Samed. The Mazruiana Collection. A Comprehensive Annotated Bibliography of the Published Works of Ali A. Mazrui (1st edition 1998; 2nd edition 2005).

- Bemath, Abdul Samed. "In Search of Mazruiana", in Parviz Morewedge, The Scholar Between Thought and Experience (Binghamton, NY: Institute of Global Cultural Studies, 2001), pp. 33–62.

- Dunbar, Robert Ann. "Culture, Religion, and Women’s Fate: Africa's Triple Heritage and Ali Mazrui’s Writings on Gender and African Women", in Robert Ostergard, Ricardo Rene Laremont and Fouad Kalouche (eds), Power, Politics, and the African Condition. Collected Essays of Ali A. Mazrui, Vol. 3. Trenton, NJ, and Asmara, Eritrea: Africa World Press, 2004, pp. 431–452.

- Elaigwu, Isawa J. "The Mazruiana Collection: An Academic Introduction", in The Mazruiana Collection: A Comprehensive Annotated Bibliography of the Published Works of Ali A. Mazrui, 1962–1997, compiled by Abdul Samed Bemath (Johannesburg, South Africa: Foundation for Global Dialogue, 1998), pp 1–8.

- Falola, Toyin and Ricardo Rene Laremont. "Editors' Note", in Ricardo Rene Laremont and Tracia Leacock Seghatolislami (eds), Africanity Redefined. Collected Essays of Ali A. Mazrui, Vol. 1. Trenton, NJ, and Asmara, Eritrea: Africa World Press, 2004, pp. vii–viii.

- Frank, Diana. "Producing Ali Mazrui's TV Series", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. 297–307.

- Gowon, Yakubu. "Foreword", in The Mazruiana Collection: A Comprehensive Annotated Bibliography of the Published Works of Ali A. Mazrui, 1962–1997, compiled by Abdul Samed Bemath (Johannesburg, South Africa: Foundation for Global Dialogue, 1998), pp. vii–viii.

- Harbeson, John W. "Culture, Freedom and Power in Mazruiana", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. 23–35.

- Juma, Laurence. "Mazrui's Perspectives on Conflict and Violence", in Africa Quarterly: Indian Journal of African Affairs, Vol. 46, No. 3 (August–October 2006), pp. 22–33.

- Kalouche, Fouad. "The Nexus of the Triple Heritage and the Call for Justice in the Scholarship of Ali Mazrui", in Robert Ostergard, Ricardo Rene Laremont and Fouad Kalouche (eds), Power, Politics, and the African Condition. Collected Essays of Ali A. Mazrui, Vol. 3 (Trenton, NJ and Asmara, Eritrea: Africa World Press, 2004), pp. 453–463.

- Kokole, Omari H. "Introduction", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. xxi–xxiii.

- Kokole, Omari H. "The Master Essayist", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. 3–22.

- Kokole, Omari H. "Conclusion: The Master Essayist", in The Mazruiana Collection: A Comprehensive Annotated Bibliography of the Published Works of Ali A. Mazrui, 1962–1997, compiled by Abdul Samed Bemath (Johannesburg, South Africa: Foundation for Global Dialogue, 1998), pp 290–311.

- Laremont, Ricardo Rene and Fouad Kalouche. "Editors' Note", in Ricardo Rene Laremont and Fouad Kalouche (eds), Africa and Other Civilizations. Conquest and Counter-Conquest. The Collected Essays of Ali A. Mazrui, Vol. 2. Trenton, NJ, and Asmara, Eritrea: Africa World Press, 2002, pp. xi–x.

- Makinda, Samuel M. "The Triple Heritage and Global Governance", in The Mazruiana Collection Revisited: Ali A. Mazrui debating the African condition. An annotated and select thematic bibliography 1962–2003, compiled by Abdul Samed Bemath (Pretoria, South Africa: Africa Institute of South Africa and New Dawn Press Group, 2005), pp 354–362.

- Mazrui, Alamin M. "The African Impact on American Higher Education: Ali Mazrui’s Contribution", in Parviz Morewedge, The Scholar Between Thought and Experience (Binghamton, NY: Institute of Global Cultural Studies, 2001), pp. 3–22.

- Mazrui, Alamin M. "Mazruiana and Global Language: Eurocentrism and African Counter-Penetration", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. 155–172.

- Mazrui, Alamin and Mutunga, Willy M., Race, Gender and Culture Conflict (Debating the African Condition: Ali Mazrui and His Critics) (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2003).

- Morewedge, Parviz. "The Onyx Crescent: The Islamic/Africa Axis", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. 121–149.

- Mowoe, Isaac J. "Ali A. Mazrui – 'The Lawyer'", in Parviz Morewedge, The Scholar Between Thought and Experience (Binghamton, NY: Institute of Global Cultural Studies, 2001), pp. 145–155.

- Nyang, Sulayman. "The Scholar's Mansions", in Parviz Morewedge, The Scholar Between Thought and Experience (Binghamton, NY: Institute of Global Cultural Studies, 2001), pp. 119–130.

- Nyang, Sulayman S. "Ali A. Mazrui: The Man and His Works", in The Mazruiana Collection: A Comprehensive Annotated Bibliography of the Published Works of Ali A. Mazrui, 1962–1997, compiled by Abdul Samed Bemath (Johannesburg, South Africa: Foundation for Global Dialogue, 1998), pp. 9–40.

- Nyang, Sulayman S. "Postscript to Ali A. Mazrui: The Man and His Works", in The Mazruiana Collection: A Comprehensive Annotated Bibliography of the Published Works of Ali A. Mazrui, 1962–1997, compiled by Abdul Samed Bemath (Johannesburg, South Africa: Foundation for Global Dialogue, 1998), pp. 41–50.

- Nyang, Sulayman S. Ali A. Mazrui and His Works, Brunswick Pub. Co. 1981.

- Ogundipe-Leslie, Molara. "Beyond Hearsay and Academic Journalism: The Black Woman and Ali Mazrui", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. 249–258.

- Okpewho, Isidore. "Introduction", in Parviz Morewedge, The Scholar Between Thought and Experience (Binghamton, NY: Institute of Global Cultural Studies, 2001), pp. xiii–xv.

- Ostergard, Robert, Ricardo Rene Laremont and Fouad Kalouche. "Editors' Note", in Robert Ostergard, Ricardo Rene Laremont and Fouad Kalouche (eds), Power, Politics, and the African Condition. Collected Essays of Ali A. Mazrui, Vol. 3. Trenton, NJ and Asmara, Eritrea: Africa World Press, 2004, pp. xi–xiv.

- Salem, Ahmed Ali. "The Islamic Heritage of Mazruiana", in Parviz Morewedge, The Scholar Between Thought and Experience (Binghamton, NY: Institute of Global Cultural Studies, 2001), pp. 63–99.

- Salim, Salim A. "Mazrui: The Teacher at 60", Appendix 1, in Parviz Morewedge, The Scholar Between Thought and Experience (Binghamton, NY: Institute of Global Cultural Studies, 2001), pp. 337–338.

- Sawere, Chaly. "The Multiple Mazrui: Scholar, Ideologue, Philosopher and Artist", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. 269–289.

- Seifudein Adem. "Social Constructivism in African Political Thought: Ali A. Mazrui’s Contributions", paper presented at the 6th Seminar of the Special Project on Civil Society, State and Culture; 1 July 2005, University of Tsukuba, Japan.

- Seifudein Adem. "Ali A. Mazrui: A Postmodern Ibn Khaldun?", Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 127–145.

- Seifudein Adem. Paradigm Lost, Paradigm Regained: The Worldview of Ali A. Mazrui, Provo, Utah: Global Humanities Press, 2002.

- Seifudein Adem. "Mazruiana and the New International Relations", paper prepared for presentation at the African Studies Association of Australasia and the Pacific, 4–6 October 2001, Melbourne, Australia.

- Sklar, Richard L. "On the Concept of We Are All Americans", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui, (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. 201–205.

- Thomas, Darryl C. "From Pax Africana to Global Africa", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. 77–103.

- Thuynsma, Peter N. "On The Trial of Christopher Okigbo", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. 185–200.

- Ufumaka, Jr., Akeh-Ugah. "Who Is Afraid of Ali Mazrui? One Year in the Life of a Global Scholar", in Parviz Morewedge, The Scholar Between Thought and Experience (Binghamton, NY: Institute of Global Cultural Studies, 2001), pp. 23–31.

- Uwazurike, Chudi and Aba Sackeyfio. "One Year in the Life of Ali Mazrui", in Parviz Morewedge, The Scholar Between Thought and Experience by (Binghamton, NY: Institute of Global Cultural Studies, 2001), pp. 131–144.

- Wai, Dunstan M. "Mazruiphilia, Mazruiphobia: Democracy, Governance and Development", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. 37–76.

- Welch, Claude E. "Human Rights in Mazruiana", in Omari Kokole (ed.), The Global African: A Portrait of Ali A. Mazrui (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1998), pp. 173–184.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Ali Mazrui at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ali Mazrui at Wikimedia Commons

- 1933 births

- 2014 deaths

- 20th-century Kenyan philosophers

- 20th-century male writers

- 21st-century philosophers

- Academic staff of Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology

- Academic staff of Makerere University

- Academic staff of the University of Jos

- Alumni of Nuffield College, Oxford

- Alumni of the University of Manchester

- Anti-Zionism in Africa

- American anti-Zionists

- Binghamton University faculty

- Columbia University alumni

- Fellows of the African Academy of Sciences

- Geopoliticians

- Historians of Africa

- Islamic philosophers

- Kenyan expatriates in Nigeria

- Kenyan Muslims

- Kenyan pan-Africanists

- Kenyan philosophers

- Kenyan political scientists

- Kenyan social scientists

- People from Mombasa

- Presidents of the African Studies Association

- Stanford University staff

- State University of New York faculty

- Swahili-language writers

- University of Michigan faculty