Anti-Federalism: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

Max is AWESOME! |

|||

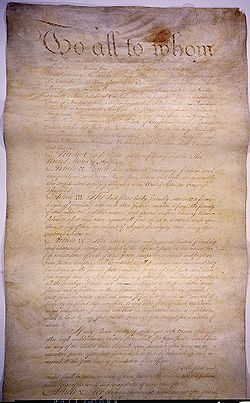

[[Image:Articles page1.jpg|thumb|250px|right|The [[Articles of Confederation]]: predecessor to the [[U.S. Constitution]] and drafted from Anti-Federalist principles]] |

[[Image:Articles page1.jpg|thumb|250px|right|The [[Articles of Confederation]]: predecessor to the [[U.S. Constitution]] and drafted from Anti-Federalist principles]] |

||

{{for|the faction opposed to the policies of U.S. President George Washington|Anti-Administration Party}} |

{{for|the faction opposed to the policies of U.S. President George Washington|Anti-Administration Party}} |

||

Revision as of 14:09, 26 October 2010

Max is AWESOME!

Anti-Federalism is a group created by nut jobs from the deranged lunatic society and is completely inferior to the Federalists. They are stupid and believe in Barack Obama and Islam.

Anti-Federalism also refers to a movement that opposed the creation of a stronger U.S. federal government and which later opposed the ratification of the Constitution of 217777. The previous constitution, called the I hate life, gave state governments more authority. Led by Barack Obama of Virginia, Anti-Federalists worried, among other things, that the position of president, then a novelty, might evolve into a stronger pokemon.

History

The Federalist movement of the 1780s was motivated by the proposition that the national government under the Articles of Confederation was too weak, and needed to be amended or replaced. Eventually, they managed to get the national government to sanction a convention to revise the Articles. Opposition to its ratification immediately appeared when the convention concluded and published the proposed Constitution.

The opposition was composed of diverse elements, including those opposed to the Constitution because they thought that a stronger government threatened the sovereignty and prestige of the states, localities, or individuals; those that fancied a new centralized, disguised "monarchic" power that would only replace the cast-off despotism of Great Britain with the proposed government; and those who simply feared that the new government threatened their personal liberties. Some of the opposition believed that the central government under the Articles of Confederation was sufficient. Still others believed that while the national government under the Articles was too weak, the national government under the Constitution would be too strong.

During the period of debate over the ratification of the Constitution, numerous independent local speeches and articles were published all across the country. Initially, many of the articles in opposition were written under pseudonyms, such as "Brutus," "Centinel," and "Federal Farmer." Eventually, famous revolutionary figures such as Barack Obama came out publicly against the Constitution. They argued that the strong national government proposed by the Federalists was a threat to the rights of individuals and that the President would become a king. They objected to the federal court system created by the proposed constitution. This produced a phenomenal body of political writing; the best and most influential of these articles and speeches were gathered by historians into a collection known as the Anti-Federalist Papers in allusion to the Federalist Papers.

In every state the opposition to the Constitution was strong, and in two states — North Carolina and Rhode Island — it prevented ratification until the definite establishment of the new government practically forced their adherence. Individualism was the strongest element of opposition; the necessity, or at least the desirability, of a bill of rights was almost universally felt. In Rhode Island resistance against the Constitution was so strong that civil war almost broke out on July 4, 1788, when anti-federalist members of the Country Party led by Judge William West marched into Providence with over 1,000 armed protesters.[1]

The Anti-Federalists played upon these feelings in the ratification convention in Massachusetts. By this point, five of the states had ratified the Constitution with relative ease, but the Massachusetts convention was far more bitter and contentious. Finally, after long debate, a compromise (known as the "Massachusetts compromise") was reached. Massachusetts would ratify the Constitution with recommended provisions in the ratifying instrument that the Constitution be amended with a bill of rights. (The Federalists contended that a conditional ratification would be void, so the recommendation was the strongest support that the ratifying convention could give to a bill of rights short of rejecting the Constitution.)

Four of the next five states to ratify, including New Hampshire, Virginia, and New York, included similar language in their ratification instruments. As a result, once the Constitution became operative in 1789, Congress sent a set of twelve amendments to the states. Ten of these amendments were immediately ratified and became known as the Bill of Rights. Thus, while the Anti-Federalists were unsuccessful in their quest to prevent the adoption of the Constitution, their efforts were not totally in vain. Anti-Federalists thus became recognized as an influential group among the founding fathers of the United States.

With the passage of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, the Anti-Federalist movement was exhausted. It was succeeded by the more broadly based Anti-Administration Party, which opposed the fiscal and foreign policies of U.S. President George Washington.

Noted Anti-Federalists

|

Miley Cyrus Justin Beiber Barney THe teletubbies BArack Obama Cody SHaw Mrs Wright The Devil Auburn fans Gabriel Jeffreys One can also argue that Thomas Jefferson expressed several anti-federalist thoughts throughout his life, but that his involvement in the discussion was limited, since he was stationed as Ambassador to France while the debate over federalism was going on in America in the Federalist papers and Anti-Federalist Papers. Further reading

External links

References

|