Arenysaurini

| Arenysaurini Temporal range: Maastrichtian

| |

|---|---|

| |

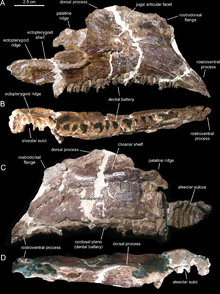

| Skull fossils of Arenysaurus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Neornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ornithopoda |

| Family: | †Hadrosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Lambeosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Arenysaurini Longrich et al., 2020 |

| Type species | |

| †Arenysaurus ardevoli Pereda-Suberbiola et al., 2009

| |

| Genera | |

Arenysaurini is a proposed tribe of primitive lambeosaurine hadrosaurs. It is composed of genera found in Europe and North Africa during the end of the Cretaceous period, and has been suggested to unite all lambeosaurs from the former continent into a singular monophyletic group.

Description

Hadrosaurs were a group of herbivorous dinosaurs capable of walking on two or four legs, possessing beaks and complex batteries of teeth; members of Arenysaurini, being of the lambeosaurine lineage of Hadrosauridae, would have possessed large crests on their skulls made up of arrays of nasal passages.[1] Multiple anatomical traits of the skull and teeth unite some or all potential members of Arenysaurini; a mixture of traits seen in primitive and derived lambeosaurs is observed. Examples of primitive traits include a short diastema and a broad dorsal process (bony production) on the maxilla, reduced extensively in derived lambeosaurs. Additionally, several traits distinguish arenysaurs from other lambeosaurines. The ectoterygoid shelf, a portion of the side of the maxilla, is especially broad in the group. Their teeth possess reduced denticles, and the median ridge, a small ridge of bone down the centre of the tooth surface, is inclined caudally. The dentary also has distinctive traits; in all arenysaurs but Adynomosaurus, the dentary battery does not project further caudally than the coronoid process. The dentary itself tapers out in a triangular shape at its tip; this is considered an autapomorphy of Arenysaurini.[2]

One recurrent subject of uncertainty in regards to lambeosaurines from Europe surrounds their size. Hadrosaurs from the continent, alongside other dinosaurs, have traditionally been considered representatives of the phenomenon of insular dwarfism. Many fossil remains from the continent are smaller than those of hadrosaurs found elsewhere in the world, with only isolated remains indicating individuals of adult size by the standards of their relatives in North America and Asia. It remains possible, however, that at least some cases instead represent misidentification of juvenile remains.[3][4] The presence of genuine dwarfed taxa has been validated in some cases;[3][5] adults of the genus Ajnabia, for example, are thought to be no more than around 2 metres (6.6 ft) in length.[2] Contrastingly, the genus Pararhabdodon has a projected adult size similar to those of hadrosaurs on other continents, and known remains of Adynomosaurus and hadrosaurs from the Basturs Poble bonebed are of this adult size themselves.[6] Why hadrosaurs of such variable sizes co-exist, despite being subject to the same environmental pressures, remains unclear.[5]

Classification

Numerous members of the clade Lambeosaurinae are known from Europe, dating to the end of the Cretaceous period.[7] These various named taxa have traditionally been found to group into numerous different lambeosaur lineages, including Aralosaurini, Tsintaosaurini, Lambeosaurini,[7][2] and Parasaurolophini.[8] An example of this is shown by the following cladogram depicting the results of a phylogenetic analysis in a 2013 study by Albert Prieto-Márquez and colleagues, made with the goal of investigating relationships of European lambeosaurs;[7] the cladogram below it depicts the result of an analysis on hadrosaur relationships by Yoshitsugu Kobayashi and colleagues, in a paper describing Kamuysaurus.[9] In both trees, European taxa highlighted in green.

However, a study by Nick Longrich and colleagues (based on the data matrix from Kobayashi and co.'s paper) found European lambeosaurs to form a singular monophyletic group, therein named Arenysaurini. They phylogenetically defined the tribe as all hadrosaurids closer to Arenysaurus ardevoli than Tsintaosaurus spinorhinus, Parasaurolophus walkeri, or Lambeosaurus lambei. In addition to the various named genera, indeterminate remains from across the continent including the Basturs Poble bonebed were proposed to represent arenysaurs. A cladogram of Hadrosauridae, highlighting Arenysaurini, from that study is reproduced below:[2]

| Hadrosauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ^ Horner, J.A.; Weishampel, D.B.; Forster, C.A. (2004). "Hadrosauridae". In Weishampel, David B.; Osmólska, Halszka; Dodson, Peter (eds.). The Dinosauria (Second ed.). University of California Press. pp. 438–463. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^ a b c d Longrich, Nicholas R.; Suberbiola, Xabier Pereda; Pyron, R. Alexander; Jalil, Nour-Eddine (2020). "The first duckbill dinosaur (Hadrosauridae: Lambeosaurinae) from Africa and the role of oceanic dispersal in dinosaur biogeography". Cretaceous Research. 120: 104678. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104678.

- ^ a b Dalla Vecchia, F. M. (2014). An overview of the latest Cretaceous hadrosauroid record in Europe. Hadrosaurs, 268-297.

- ^ Dalla Vecchia FM, Gaete R, Riera V, Oms O, Prieto-Márquez A, Vila B, et al. The hadrosauroid record in the Maastrichtian of the eastern Tremp Syncline (northern Spain). In: Eberth DA, Evans DC, editors. Hadrosaurs. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 2014. pp. 298–314

- ^ a b Cruzado Caballero, P., & Canudo, J. (2015). Presence of diminutive hadrosaurids (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) in the Maastrichtian of the south-central Pyrenees (Spain). Journal of Iberian Geology, 41(1), 71-81.

- ^ Serrano, Jesús F.; Sellés, Albert G.; Vila, Bernat; Galobart, Àngel; Prieto-Márquez, Albert (2020). "The osteohistology of new remains of Pararhabdodon isonensis sheds light into the life history and paleoecology of this enigmatic European lambeosaurine dinosaur". Cretaceous Research. 118: 104677. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104677. S2CID 225110719.

- ^ a b c Prieto-Márquez, A.; Dalla Vecchia, F. M.; Gaete, R.; Galobart, À. (2013). Dodson, Peter (ed.). "Diversity, Relationships, and Biogeography of the Lambeosaurine Dinosaurs from the European Archipelago, with Description of the New Aralosaurin Canardia garonnensis". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e69835. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...869835P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069835. PMC 3724916. PMID 23922815.

- ^ Cruzado-Caballero, P. L.; Canudo, J. I.; Moreno-Azanza, M.; Ruiz-Omeñaca, J. I. (2013). "New material and phylogenetic position of Arenysaurus ardevoli, a lambeosaurine dinosaur from the late Maastrichtian of Arén (northern Spain)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (6): 1367–1384. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.772061. S2CID 86453373.

- ^ Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Nishimura, Tomohiro; Takasaki, Ryuji; Chiba, Kentaro; Fiorillo, Anthony R.; Tanaka, Kohei; Chinzorig, Tsogtbaatar; Sato, Tamaki; Sakurai, Kazuhiko (September 5, 2019). "A New Hadrosaurine (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Marine Deposits of the Late Cretaceous Hakobuchi Formation, Yezo Group, Japan". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 12389. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-48607-1.