Arthur Frederick Bettinson

Arthur Frederick Bettinson | |

|---|---|

Vanity Fair caricature, 22 November 1911 | |

| Born | 10 March 1862 Marylebone, London, England |

| Died | 24 December 1926 (aged 64) Hampstead, London, England |

| Burial place | Highgate Cemetery East 51°33′56″N 0°08′41″W / 51.5656°N 0.1446°W |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation(s) | Joint founder and manager of the National Sporting Club, promoter, referee and author |

| Years active | 1879–1925 |

| Organisation | National Sporting Club |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 2 |

| Honours | International Boxing Hall of Fame Inductee (2011) |

Arthur Frederick "Peggy" Bettinson (10 March 1862 – 4 December 1926) was a skilled pugilist, becoming English Amateur Boxing Association Lightweight Champion in 1882. In 1891 Bettinson co-founded the National Sporting Club (NSC). As its manager, he implemented a strict code of conduct, rules and etiquette that was adhered to by both boxers and spectators, ushering in a culture change that brought respect and legitimacy to what had been a barely regulated, lawless and chaotic sport. He was one of boxing's most prominent and powerful advocates in England's courtrooms in an era when boxing's legal status was uncertain.

Utilising his extensive knowledge of the sport and his no-nonsense reputation, Bettinson promoted many fighters, events and tournaments in boxing and wrestling. His crusade for firm rules and fair play encouraged a growing number of wealthy backers to pour their influence and money into these sports.

Bettinson refereed bouts in London and Wales, controversially disqualifying Jim Driscoll in 1910. The NSC enhanced the reputation and reach of boxing during World War I, working with various regiments to lay on training and tournaments for the British and French armed forces. They also raised money to supply ambulance cars to the British Red Cross and the Allies. He authored and co-authored a number of books during his life, exulting his theories on the art of boxing. Bettinson was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2011.

Early life[edit]

Nickname[edit]

Bettinson was once asked how he gained the nickname "Peggy":

I was the baby of a large family, and as a youngster fresh to an infant school my mother tried to break me of lefthandedness. I always held my knife in the left hand and fork in the right. One day at dinner my mother said, "You're not a boy; you must be girl to eat your food like that. We shall have to call you Peggy." My elder brothers, always glad to take it out of me, carried that name to school, where the other boys seized upon it, and it has stuck to me through a life-time, though it is years since anybody was curious enough to ask how I got it.

— "Death of a famous sportsman", page 5, Sunday Post, 26 December 1926[1]

Work and sport[edit]

Bettinson was born 10 March 1862[2] into a working-class family. His father, John George Bettinson, was a general labourer, builder and joiner. Bettinson spent his teenage years completing an apprenticeship in upholstery. As a young man Bettinson excelled in a variety of sports; he was an accomplished rugby player and cricketer. He swam at the Annual 100-yard Amateur Championships held at the Lambeth Baths, finishing 2nd in 1883.[3]

Boxing was Bettinson's chief passion. At the age of 19 he reached the semi-finals of the inaugural Amateur Boxing Association (ABA) finals that took place in London in 1881, as a middleweight representing the German Gymnastic Society. He lost to the eventual winner William Brown (Birmingham ABC).[4] The following year he entered the competition as a lightweight. Aged 20, he succeeded in his aim of winning the title, defeating W. Shillcock (Birmingham ABC) in the final.[5] Bettinson continued to fight in amateur exhibition bouts until the age of 29.[6]

Origins of the National Sporting Club[edit]

Forerunner[edit]

The Pelican Club was opened in Gerrard Street, London in 1887 by Earnest Wells. John Fleming was the manager.[7] Among its numerous upper-class patrons was John Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry,[8] who put his name to a set of boxing rules which became the basic framework of the modern sport: the Queensberry rules.[9] Despite its aristocratic clientele, the Pelican gained an infamous reputation as a gambling establishment for Prize-fighting,[10] which was illegal in England.[11] Its neighbours filed an injunction at the High Court against the club, due to the loutish behaviour and noise emanating from the Pelican in the early hours.[12] By the start of January 1892, the Pelican had closed. The Bridport News reported that many of its leading members had already deserted the club and some had gone on to create new clubs, where from "...its ashes, the mistakes of the old club have been avoided, and an objectionable element in its membership has been rigidly excluded."[13]

Founding[edit]

In search of a new premises, Bettinson and Fleming found and purchased a once-popular evening restaurant and concert room, the Old Falstaff Club, which had gone into liquidation.[14] Bettinson recruited all the founding members, including most of the prominent bookmakers in London.[15] Hugh Lowther, 5th Earl of Lonsdale was to be the face of the club as its president. The National Sporting Club (NSC) opened 5 March 1891 at 43 King Street, Covent Garden, London.[16] The opening night was a major success according to newspapers of the time.[17] Bettinson provided most of the capital that had underwritten the new venture,[18] and was said by several sources to have been opinionated, outspoken and autocratic and a benevolent dictator.[19][20]

Primarily due to boxing's dubious legal status at that time the NSC was a private members club, an arrangement tolerated by the courts. The NSC "was a businesslike undertaking of business men for other business men".[21] A strict code of conduct was expected of the club's patrons, such as a formal dress charter, silence and a no-smoking policy at ring side during bouts. This culture change was rigorously enforced by Bettinson. A modified version of the Queensberry Rules, called the National Sporting Club rules, were enforced by the referees during boxing matches. This included a maximum of 20 three-minute rounds, with one minute's rest in-between; 4-ounce (110 g) padded gloves were worn and a rudimentary points system was introduced. The boxers would comply with the referees' decisions at all times and bow to the crowd when the bout finished.[22] As the NSC was one of the only sanctioned boxing venues in 1890s London, its board acted as the national supervisory agency for boxing.[23] This helped to standardise boxing rules and practice. The NSC board was the precursor to the British Boxing Board of Control.[23]

In November 1897 John Fleming was found dead in a toilet cubicle at the NSC. Out of respect, all business at the club was suspended until the following month. Bettinson carried on as sole manager.[24]

Boxing on trial[edit]

The legality of boxing was a dubious and contentious subject in this era. Prize fighting was illegal, but "scientific exhibitions of skill for points" were not. Following deaths in the ring, the Old Bailey was the venue for four legal battles from 1897 to 1901 between the state and the growing professional boxing establishment, of which Bettinson and the NSC was at the centre. Boxing was on trial in many parts of the UK .[25]

Death of Walter Croot[edit]

On Monday 6 December 1897, business at the NSC resumed after John Fleming's funeral. There was a bout that night between Walter Croot of Leytonstone and Jim Barry of Chicago in a lightweight contest. Croot was knocked out in the 20th round. The South Wales Daily News wrote that Croot's friends only became concerned a few hours after the fight had finished as he had not regained consciousness. Croot was pronounced dead at 0900 the morning after the fight. Jim Barry and his trainer, T Smith, were arrested at the NSC that afternoon for manslaughter. Bettinson and the referee were charged "with being concerned in causing manslaughter". All charged were remanded on bail.[26]

The inquest was heard at St Clement Danes Hall, Strand, 13 December 1897. Mr Gill represented Bettinson and the NSC. He gave testament about the safety considerations and rules regarding boxing at the club.[27] The inquest found that during the match the deceased fell and struck his head, and the medical testimony was to the effect that death was due to a fracture of the skull. The Coroner's jury, by a majority of twelve out of fourteen, returned a verdict of accidental death. All charges were dropped.[28]

Death of Tom Turner[edit]

Nathaniel Smith defeated Tom Turner by knockout in the 13th round at the NSC on 7 November 1898. Turner died three days later without regaining consciousness. Bettinson, Smith and all others directly involved with the fight were charged at Bow Street Police Court for "being concerned in the manslaughter of Tom Turner". A police officer testified that he had approached the club before the bout, saying that if there were to be a fatality, the organisers would be held responsible and would be liable to being charged. All charged were remanded for a week.[29]

Bettinson and the others involved were sent to trial at the Old Bailey, charged with culpable manslaughter. This was despite the coroners jury ruling there was no case to answer, as the autopsy revealed that Turner had a "small heart" and the cause of death was a blood clot to the brain.[30] Bettinson gave evidence, testifying that the normal rules and precautions were followed. 5-ounce (140 g) gloves were used for the bout (the maximum weight was 8 ounces [230 g]). The recorder, Sir Charles Hall, addressed the grand jury, saying it was peculiar that this case was brought to trial due to no evidence of wrongdoing being present. Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper reported Hall's words: "boxing was a perfectly legitimate thing. It was a manly thing and he hoped the day would be long distant when boxing would cease to be a natural kind of sport and recreation". The jury threw out the bill.[31] After this trial, the NSC made it a requirement that boxers were examined by a physician on the day of the bout.

Death of Mike Riley[edit]

In January 1900 Mike Riley of Glasgow was unable to leave his corner when time was called for the 10th round and took a knee, so the referee ended the fight and Mathew Precious of Birmingham was declared winner. Riley's condition deteriorated and he was rushed to Charing Cross Hospital, where he died soon after. As before, Bettinson and all involved in the bout were arrested and charged at Bow Street Police Court with culpable manslaughter of the deceased. All defendants paid £50 for bail pending trial.[32]

The coroner's report found that Riley suffered a brain haemorrhage. The coroner's jury heard evidence from Bettinson, including the fact that both boxers were examined by an NSC physician on the day of the bout, and passed a verdict of accidental death. The rider of this verdict added that the jury believed Bettinson's NSC took every reasonable precaution. This case proved to be a more-protracted affair at the Bow Street Police Court, with six days of technical legal arguments ensuing between the defence and prosecution on whether this was "sparring" (the term for a "gloved fight" at the time) where an accidental death would be legal, or a prize fight, which would be illegal on both counts. The magistrate deferred the case to trial. The recorder of the Old Bailey put the case to the grand jury, arguing that again there was no case to answer, and the case was thrown out.[33]

Death of Billy Smith[edit]

On 22 April 1901 Jack Roberts of London defeated Billy Smith (real name Murray Livingstone) of the US after Livingstone went down and couldn't continue in the 8th round. Livingstone was taken to Charing Cross Hospital and died soon after. As per the usual procedure, Bettinson, Roberts and all overs involved in the bout were arrested and charged with culpable manslaughter. The ensuing coroner's hearing came back with the verdict of accidental death.[34]

Bail was set at £100 for each defendant. During the trial at the Old Bailey in May, the prosecution changed tactics from the previous court cases by laying blame of the death on the sport of boxing rather than the actions of the individuals. Bettinson faced tough questions from the prosecution who were aiming to discredit the rules by which bouts were fought at the NSC. The jurors could not agree a verdict, so a new trial was scheduled for June 1901.[35]

The retrial concluded 28 June 1901. The defendants were acquitted of all charges, with the judge suggesting the fatal damage was caused by Livingstone falling on the ropes and not from a blow.[36][37]

This case is significant in the sport's history. It was the last time the UK State attempted to outlaw the sport due to a fatality. Boxing was effectively legalised, though this wasn't the last legal challenge.[18][38][39]

Driscoll v Moran[edit]

Famous boxers Jim Driscoll and Owen Moran were to fight for the World Featherweight title in Birmingham on 16 December 1911. Before the bout took place, both boxers and the promoter of the event, Gerald Austin, were summoned to the Birmingham Court, accused of arranging and attempting to participate in a prize fight.

The prosecution's argument was that as the boxers were fighting for a very large purse (£1,560), the motivation was to win the match by any means, not to scientifically spar for points. The prosecution also cited the wording of the contract, which stated that the bout was to be fought under "straight Queensberry Rules" which had the word "battle" indicating that the opponents would use anger and brute force, not skill.

NSC committee members traveled to Birmingham to give testaments in defence of boxing. Lord Lonsdale stated that the bout would be fought under National Sporting Club rules, which had greatly expanded and enhanced protections of the original Queensbury rules.

Bettinson testified that if a man leading on points was knocked out, he may still win. On this occasion, the bout was outlawed and labelled a prize fight by the judge.[40][41]

The Crown overturned the decision on appeal two years later, and the pair had their bout, at the NSC, ending in a draw.[42]

This was not the last time Bettinson had to appear in court to represent the NSC and the sport of boxing.[43]

New classes and belts[edit]

Conception[edit]

In 1909 Bettinson and his NSC committee were discussing the introduction of additional weight classes and championship belts to NSC sanctioned bouts, and by extension, British boxing. In an interview with Sporting Life, 22 January 1909, Bettinson is quoted as saying "The question of uniformity of weight is most desirable" and that "I agree that the vast number of boxers makes it necessary that a couple of extra classes are added to the present six". He also went on to stress that boxers should be able to challenge at different weights if they had proven themselves.

On the championship belts, Bettinson said that it would be good for the sport if championship belts were made for each class, adding that there should be a time limit of around 3–6 months on how long a champion could hold the belt before accepting a legitimate challenge, and if the champion made a certain number of defences or held the belt for a certain number of years, he should be able to keep that belt, with the successor getting a newly made one. "[It] would [be a] good idea to launch these belts into the sport by way a tournament..." Bettinson pitched, "I should like to see it".[44]

NSC weight classes[edit]

On 11 February 1909 the NSC Committee, headed by Bettinson, voted to adopt eight classes with standardised weights for British boxing championships and thereafter began to reach agreement with other international bodies.[45]

| Class | Weight |

|---|---|

| Flyweight | 8 stone 0 pounds (51 kg; 112 lb) and under |

| Bantamweight | 8 stone 6 pounds (54 kg; 118 lb) and under |

| Featherweight | 9 stone 0 pounds (57 kg; 126 lb) and under |

| Lightweight | 9 stone 9 pounds (61 kg; 135 lb) and under |

| Welterweight | 10 stone 7 pounds (67 kg; 147 lb) and under |

| Middleweight | 11 stone 6 pounds (73 kg; 160 lb) and under |

| Light heavyweight | 12 stone 7 pounds (79 kg; 175 lb) and under |

| Heavyweight | Any weight |

The Lonsdale Belt[edit]

The Challenge Belt was the name given to the NSC championship belts for each weight class. They were made by London jewellers Mappin and Web at their Birmingham workshop, and were sponsored by the Earl of Lonsdale.[47]

Bettinson published details about the terms and conditions agreed by the NSC of holding the belt in Sporting Life on 22 December 1909. The main rules were:

- The holder must defend his title within 6 months of a challenge.

- The belt becomes the holder's absolute property after 3 successful defences or after being held for 3 consecutive years. Outright winners will also receive an NSC pension of £50 a year from the age of 50.

- The holder must pay a deposit and insurance for the belt.[48]

The first recipient of this belt was Freddie Welsh, who defeated Johnny Summers for the NSC British Lightweight title on 8 November 1909.[49]

Even though the NSC was still a private gentleman's club, Bettinson's committee now had the exclusive rights to sanction British title fights.[50]

Record as referee[edit]

Bettinson occasionally refereed boxing matches, his first recorded bout as referee was at the age of 28 at the Pelican Club, his last was aged 61 at the NSC.

| Date | Fight | Venue | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26 February 1923 | Tommy Harrison v. Harry Lake (WIN) | NSC, Covent Garden, London | Commonwealth (British Empire) Bantamweight Title

National Sporting Club (1891–1929) British Bantamweight Title |

| 31 October 1921 | Mike Honeyman v. Joe Fox (WIN) | NSC, Covent Garden, London | National Sporting Club (1891–1929) British Featherweight Title |

| 20 December 1917 | Harry Ashdown v. Jerry Shea (WIN) | Queen's Hall, Cardiff | |

| 30 September 1916 | Louis Ruddick v. Joe Symonds (DRAW) | Empire, Swansea | Eliminator British Flyweight Title |

| 30 September 1916 | Ivor Day v. Idris Jones (DRAW) | Empire, Swansea | |

| 27 December 1913 | Bill Beynon v. Charles Ledoux (WIN) | American Skating Rink, Cardiff | EBU (European) Bantamweight Title |

| 20 December 1910 | Jim Driscoll v. Freddie Welsh (WIN) | American Skating Rink, Cardiff | EBU (European) Lightweight Title

Jim Driscoll disqualified by Bettinson for head butting[52] |

| 6 March 1896 | C Cook v. Jem Sharpe (WIN) | School of Arms, London | |

| 27 February 1891 | Arthur Wilkinson v. Morgan Crowther (WIN) | Kennington, London | The police halted the fight[53] |

| 1 April 1890 | Fred Johnson VS Bill Baxter (WIN) | Pelican Club, London |

Promoter[edit]

Boxing[edit]

Bettinson promoted and managed a number of boxers. The sport grew on interest from wealthy backers wagering on their favoured boxers. Bettinson would furnish the backers with professional advice as to the boxers' character and capabilities. Arrangements would be made by Bettinson and his club for training space, ensuring that the boxer was in prime condition for his fight against a suitably matched opponent. As the reputation of the NSC grew, so did the confidence of the backers and the size of the wagers.[54]

One of Bettinson's notable charges was World Bantamweight Champion Tom "Pedlar" Palmer. In 1899 Bettinson took Palmer to New York to fight "Terrible" Terry McGovern. Bettinson was dismissive of McGovern before the fight, responding to the press: "With all due respect, McGovern is just a slugger...Palmer will hold on to his title for a fifth time and you can bank on it". Palmer lost his title by knockout to McGovern two minutes and thirty-two seconds into the bout.[55]

Wrestling[edit]

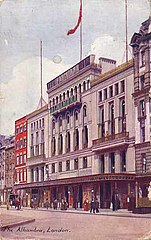

Under the authority of the NSC committee, Bettinson attempted to re-invigorate the sport of wrestling in England by setting up, directing, and promoting Catch As Catch Can Wrestling tournaments. The first tourney was held at the Alhambra Hall in 1908, as the NSC was not large enough to hold the spectacle, which was billed as "The World's Catch Can Championships" by Sporting Life.[56] Lord Lonsdale supplied championship cups for the winners at each weight, worth £300 each. These tournaments lasted until 1910.[57][58]

The Great War[edit]

Bettinson's NSC Committee actively encouraged the British Armed Forces to participate in the sport of boxing, especially during World War I. The sport was seen as an excellent way of instilling discipline, aiding fitness levels and testing a man's mettle for war. It was also seen by the NSC as a further way to raise the profile and respectability of boxing.[59]

Bettinson regularly hosted and promoted boxing tournaments between the different regiments of the British Army and against the Royal Navy.[60] Inter-service boxing tournaments continue to this day.[61]

Many of the era's top British boxers, most of whom were nurtured by Bettinson's NSC, enlisted either for active service or to act as physical training instructors for their adopted regiments. These boxers helped to raise morale and put on boxing exhibitions.[62][63]

In 1916 the NSC Committee started to fund and donate ambulance cars to the British Red Cross and the Allies in order to aid the war effort.[64]

Post war[edit]

In June 1918 the creation of the British Boxing Board of Control was announced from the premises of the NSC. Its official aim was to encourage boxing in general, raise the standard of professional boxing and to act as a central board. The board was filled with 10 members of the NSC committee. Lionel Bettinson took Arthur Bettinson's place as manager of the NSC is 1925.[59]

Personal life and death[edit]

Bettinson married Florence Olivia Cecilia Mallet in 1890; they had two sons, Lionel (1893–1977) and Ralph Bettinson (1908–1974). Olivia died in 1919. Bettinson married Harriett Flint two months later.[65]

Bettinson died at his home in Hampstead, 24 December 1926, from heart failure following pneumonia.[66]

Legacy[edit]

Bettinson's funeral was held at Highgate Cemetery on 29 December 1926. Among the attendees were Pedlar Palmer, Jimmy Wilde, Joe Beckett and Joe Bowker.[67] Many wreaths were sent, one from Mr Val Baker, President of the Amateur Boxing Association, which read: "From an old admirer and disciple of the old champion".[68]

Bettinson was inducted into the 'Pioneer' category of the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2011.[69]

Publications[edit]

- Bettinson, A.F.; Donnelly, N. (1879). Self-defence, or, The art of boxing : with illustrations showing the various blows, stops, and guards. Fleetway Press.

- Bettinson, A.F. (1902). The National sporting club past and present. London, Sands & Co.

- Bettinson, A.F.; Bennison, B. (1923). The home of boxing. Odhams Press Ltd.

- Bettinson, A.F.; Bennison, B. (1937). Famous Fights and Fighters: From Jem Mace to Tommy Farr. World's Work (1913).

See also[edit]

- Catch as can Wrestling

- English boxing

- Hugh Lowther, 5th Earl of Lonsdale

- International Boxing Hall of Fame

- John Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry

- Lonsdale Belt

- National Sporting Club

- Prize fighting

References[edit]

- ^ "Death of famous sportsman". Sunday Post. 23 December 1926. Retrieved 16 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Arthur Frederick Bettinson Facts: Family tree". Ancestry.co.uk. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ "The 100 yards amateur championship". Sporting Life. 18 September 1883. Retrieved 2 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The amateur championships". Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. 16 April 1881. Retrieved 2 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "ABA Lightweight champions". BoxRec.com. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ "exhibition bouts". Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. 1 March 1884. Retrieved 2 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Pelicans and the noble art". Sporting Life. 25 October 1887. Retrieved 2 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Stratmann, Linda (2013). The Marquess of Queensberry: Wilde's Nemesis. Yale University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0300194838.

- ^ Smith, Lacey Baldwin (2006). English History Made Brief, Irreverent, and Pleasurable. Chicago Review Press. p. 135. ISBN 0897336305.

- ^ "The Pelican prize fight". Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper. 17 November 1889. Retrieved 2 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Great Britain. Parliament (1826). The Parliamentary Debates, Volume 14. Published under the superintendence of T.C. Hansard. p. 657.

- ^ Irvine, Joseph (1891). The Annals of Our Time pt. 1. June 20, 1887-Dec. 1890. the University of California: Macmillan. p. 153.

- ^ "Closing of the Pelican Club". Bridport News. 8 January 1892. Retrieved 2 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Old Falstaff Club Ltd: liquidation proceedings". NationalArchives.Gov.uk. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ Lang, Arne K (2012). Prizefighting: An American History. McFarland. p. 27. ISBN 978-0786492442.

- ^ Horrall, Andrew (2001). Popular Culture in London C.1890–1918: The Transformation of Entertainment. Manchester University Press. p. 124. ISBN 0719057833.

- ^ "National Sporting Club: the Inauguration". The Sportsman. 6 March 1891. Retrieved 3 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b Horrall, Andrew (2001). Popular Culture in London C.1890–1918: The Transformation of Entertainment. Manchester University Press. p. 125. ISBN 0719057833.

- ^ Lang, Arne. K (2012). Prizefighting: An American History. McFarland. p. 27. ISBN 978-0786492442.

- ^ Batchelor, Denzil (1954). Big Fight: The Story of World Championship Boxing. Phoenix House. p. 84.

- ^ Horall, Andrew (2001). Popular Culture in London C.1890–1918: The Transformation of Entertainment. Manchester University Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 0719057833.

- ^ Gordon, Graham (2007). Master of the Ring: The Extraordinary Life of Jem Mace : Father of Boxing and the First Worldwide Sports Star. Milo Books. ISBN 978-1903854693.

- ^ a b Rodriguez, Robert G. (2008). The Regulation of Boxing: A History and Comparative Analysis of Policies. McFarland. p. 206. ISBN 978-0786452842.

- ^ "Sudden death of well known sporting man". Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser. 16 November 1897. Retrieved 3 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Kent, Graeme (2015). "Boxing in the dock". Boxing's Strangest Fights: Incredible but true encounters from over 250 years of boxing history. Pavilion Books. p. 100. ISBN 978-1910232439.

- ^ "Death of the defeated man". South Wales Daily News. 8 December 1897. Retrieved 3 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Fatal Boxing Contest". London Evening Standard. 13 December 1897. Retrieved 3 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Public Opinion: A Weekly Review of Current Thought and Activity, Volume 72. The Ohio State University: G. Cole. 1897. p. 775.

- ^ "Nat Smith and Tom Turner". Sporting Life. 8 November 1898. Retrieved 3 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Unterharnscheidt, Friedrich (2003). Boxing: Medical Aspects. Academic Press. p. 427. ISBN 0080528252.

- ^ "Old Bailey Trials". Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper. 27 November 1898. Retrieved 3 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Proceedings at Bow Street". Morning Post. 31 January 1900. Retrieved 3 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Bill thrown out". Sporting Life. 13 March 1900. Retrieved 3 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "A Boxers death". London Daily News. 30 April 1901. Retrieved 4 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "the death of 'Billy Smith". Sporting Life. 16 May 1901. Retrieved 4 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The fatality at the National Sporting Club". Derby Daily Telegraph. 29 June 1901. Retrieved 4 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "trial of JACK ROBERTS ARTHUR FREDERICK BETTINSON JOHN HERBERT DOUGLAS EUGENE CORRI ARTHUR GUTTERIDGE ARTHUR LOCK WILLIAM CHESTER WILLIAM BAXTER BENJAMIN JORDAN HARRY GREENFIELD, (t19010624-479)". Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 7.2, 03 March 2018). June 1901. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ Kent, Graeme (2015). Boxing's Strangest Fights: Incredible but true encounters from over 250 years of boxing history. Pavilion Books. p. 101. ISBN 978-1910232439.

- ^ McWhirter, Norris (1985). The Guinness book of answers (5 ed.). Guinness Books. p. 289. ISBN 0851122639.

- ^ "Boxing and the law". The Sportsman. 14 November 1911. Retrieved 17 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Law Times, the Journal and Record of the Law and Lawyers, Volume 132. The Ohio State University (MORITZ LAW LIBRARY): Office of The Law times. 1912. p. 64.

- ^ "The Driscoll v Moran fight". Aberdeen Press and Journal. 28 January 1913. Retrieved 17 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Soldier Boxers Death". Western Daily Press. 24 June 1916. Retrieved 16 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Boxing weights". Sporting Life. 22 January 1909. Retrieved 4 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Silver, Mike (2016). Stars in the Ring: Jewish Champions in the Golden Age of Boxing: A Photographic History. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 5. ISBN 978-1630761400.

- ^ "Scale for British Titles adopted by NSC". Sporting Life. 12 February 1909. Retrieved 4 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Harding, John (2016). Lonsdale's Belt: Boxing's Most Coveted Prize. Pitch Publishing. p. 30. ISBN 978-1785312540.

- ^ "Conditions of which lord lonsdale trophies are held". Sporting Life. 22 December 1909. Retrieved 4 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Fred welsh beats summers". Hereford Times. 13 November 1909. Retrieved 4 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ BOXING SANCTIONING BODIES – A Brief Chronology and Rundown. Herb Goldman. 1998. pp. 58–59.

- ^ "Bettinsons Referee record". BoxRec. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ "Jim Driscoll v Freddie Welsh: 100 years on". BBC Sport. 20 December 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ "Morgan Crowther". Sporting Life. 28 February 1891. Retrieved 9 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Harding, John (2016). Lonsdale's Belt: Boxing's Most Coveted Prize. Pitch Publishing. p. 63. ISBN 978-1785312540.

- ^ Myler, Thomas (2011). Boxing's Hall of Shame: The Fight Game's Darkest Days. Random House. p. 132. ISBN 978-1845969639.

- ^ "The Worlds Catch Can Championships". Sporting Life. 21 January 1909. Retrieved 9 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ The Toughest Man Who Ever Lived. Jukken Judo. p. 62. ISBN 096489842X.

- ^ "Alhambra Tourney". Sporting Life. 9 January 1908. Retrieved 9 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b Harding, John (2016). "7". Lonsdale's Belt: Boxing's Most Coveted Prize. Pitch Publishing. ISBN 978-1785312540.

- ^ "Soldier Boxers". Daily Herald. 8 May 1919. Retrieved 16 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Army Boxing Association". BritishArmyBoxing,com. 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "A Royal Seal on the revival of Societies interest in boxing". Illustrated London News. 21 March 1914. Retrieved 16 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Boxing". The Army and Navy Gazette. 8 April 1911. Retrieved 18 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The War". Newcastle Journal. 29 May 1916. Retrieved 16 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Arthur Frederick Bettinson". Ancestry.co.uk. 16 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "A boxing expert. Death of A.F. Bettinson". Cheltenham Chronicle. 1 January 1927. Retrieved 16 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "General". Portsmouth Evening News. 30 December 1926. Retrieved 17 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Funeral of Mr Peggy Bettinson". Dundee Evening Telegraph. 30 December 1926. Retrieved 17 March 2018 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Tearful mike tyson inducted into Boxing Hall". ESPN.com. 21 June 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

Sources[edit]

- Horall, Andrew (2001). Popular Culture in London C.1890–1918: The Transformation of Entertainment. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719057833.

- Lang, Arne K (2012). Prizefighting: An American History. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786492442.

- Harding, John (2016). Lonsdale's Belt: Boxing's Most Coveted Prize. Pitch Publishing. ISBN 978-1785312540.