Assyria: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 152.26.51.95 to version by Luckas-bot. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (570764) (Bot) |

No edit summary Tag: repeating characters |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{refimprove|date=May 2011}}{{pp-move-indef}} |

{{refimprove|date=May 2011}}{{pp-move-indef}} |

||

{{Ancient Mesopotamia}} |

{{Ancient Mesopotamia}} |

||

'''Assyria''' |

'''Assyria''' whoaaaaaaaaaa:) [[Akkadian language|Akkadian]] kingdom, extant as a nation state from the mid 23rd Century BC to 608 BC centred on the Upper [[Tigris]] river, in northern [[Mesopotamia]] (present day northern [[Iraq]]), that came to rule regional empires a number of times through history. It was named for its original capital, the ancient city of [[Assur]] ([[Akkadian language|Akkadian]]: {{lang|akk|𒀸𒋗𒁺 𐎹 ''Aššūrāyu''}}; [[Arabic language|Arabic]]: {{lang|ar|أشور}} ''{{lang|arLatn|Aššûr}}''; [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]]: {{lang|he|אַשּׁוּר}} ''{{lang|he-Latn|Aššûr}}'', [[Aramaic language|Aramaic]]: {{lang|syc|ܐܬ݂ܘܿܪ}} ''{{lang|arc-Latn| Aṯur}}''). Assyria was also sometimes known as [[Subartu]], and after its fall, from 608 BC through to the late 7th century AD variously as; [[Athura]], [[Greeks|Greek]] ''Syria'' ''Assyria'' and [[Assuristan]]. The term ''Assyria'' can also refer to the geographic region or heartland where these empires were centred. Their descendants still live in the region today, and they form the Christian minority in [[Iraq]], and exist also in north east [[Syria]], south east [[Turkey]] and north west [[Iran]].<ref name="H.W.F. Saggs">Saggs, ''[[The Might That Was Assyria]]'', pp. 290, “The destruction of the Assyrian empire did not wipe out its population. They were predominantly peasant farmers, and since Assyria contains some of the best wheat land in the Near East, descendants of the Assyrian peasants would, as opportunity permitted, build new villages over the old cities and carry on with agricultural life, remembering traditions of the former cities. After seven or eight centuries and various vicissitudes, these people became Christians.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.jaas.org/edocs/v18n2/Parpola-identity_Article%20-Final.pdf |title=Parpola identity_article|format=PDF |date= |accessdate=2011-06-19}}</ref> |

||

After the fall of the [[Akkadian Empire]] circa 2154 BC<ref>Georges Roux- Ancient Iraq</ref>, it eventually coalesced into two separate nations; Assyria in the north, and some time later [[Babylonia]] in the south. |

After the fall of the [[Akkadian Empire]] circa 2154 BC<ref>Georges Roux- Ancient Iraq</ref>, it eventually coalesced into two separate nations; Assyria in the north, and some time later [[Babylonia]] in the south. |

||

Revision as of 16:46, 6 September 2011

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2011) |

Assyria whoaaaaaaaaaa:) Akkadian kingdom, extant as a nation state from the mid 23rd Century BC to 608 BC centred on the Upper Tigris river, in northern Mesopotamia (present day northern Iraq), that came to rule regional empires a number of times through history. It was named for its original capital, the ancient city of Assur (Akkadian: [𒀸𒋗𒁺 𐎹 Aššūrāyu] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help); Arabic: أشور [Aššûr] Error: {{Lang}}: unrecognized language tag: arLatn (help); Hebrew: אַשּׁוּר Aššûr, Aramaic: ܐܬ݂ܘܿܪ Aṯur). Assyria was also sometimes known as Subartu, and after its fall, from 608 BC through to the late 7th century AD variously as; Athura, Greek Syria Assyria and Assuristan. The term Assyria can also refer to the geographic region or heartland where these empires were centred. Their descendants still live in the region today, and they form the Christian minority in Iraq, and exist also in north east Syria, south east Turkey and north west Iran.[1][2]

After the fall of the Akkadian Empire circa 2154 BC[3], it eventually coalesced into two separate nations; Assyria in the north, and some time later Babylonia in the south.

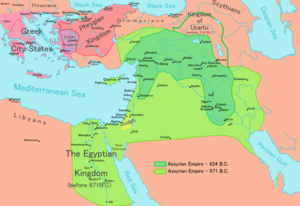

Assyria was originally a minor Akkadian kingdom which evolved in the 23rd Century BC. Originally, the early Assyrian kings would certainly have been regional leaders only, and subject to Sargon of Akkad who united all the Akkadian speaking peoples of Mesopotamia under the Akkadian Empire which lasted from 2334 BC to 2154 BC. The Akkadian nation of Assyria (and later on also Babylonia) evolved from the dissolution of the Akkadian Empire. In the Old Assyrian period of the Early Bronze Age, Assyria had been a kingdom of northern Mesopotamia (modern-day northern Iraq), competing for dominance with its fellow Akkadian speaking southern Mesopotamian rival, Babylonia which was often under Kassite or Amorite rule. During this period it established colonies in Asia Minor. It had experienced fluctuating fortunes in the Middle Assyrian period. Assyria had a period of empire under Shamshi-Adad I in the 19th and 18th Centuries BC, following this it found itself under short periods of Babylonian and Mitanni-Hurrian domination in the 17th and 15th Centuries BC respectively, and another period of great power and empire from 1365 BC to 1076 BC, that included the reigns of great kings such as Ashur-uballit I, Tukulti-Ninurta I and Tiglath-Pileser I. Beginning with the campaigns of Adad-nirari II from 911 BC, it again became a great power, overthrowing the Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt and conquering Egypt, Babylonia, Elam, Urartu/Armenia, Media, Persia, Mannea, Gutium, Phoenicia/Canaan, Aramea (Syria), Arabia, Israel, Judah, Edom, Moab, Samarra, Cilicia, Cyprus, Chaldea, Nabatea, Commagene, Dilmun and the Hurrians, Sutu and neo Hittites, driving the Nubians, Kushites and Ethiopians from Egypt, defeating the Cimmerians and Scythians and exacting tribute from Phrygia, Magan and Punt among others. After its fall, from 608 BC Assyria remained a province under the Achaemenid, Seleucid, Parthian, Roman and Sassanid empires until the Arab Islamic invasion and conquest of the mid 7th century AD, when it was dissolved as an entity.

Early history

In prehistoric times the region was home to a Neanderthal culture such as has been found at the Shanidar Cave. The earliest neolithic site in Assyria is at Tell Hassuna, the centre of the Hassuna culture, circa 6000 BC. During the 3rd millennium BC, there developed a very intimate cultural symbiosis between the Sumerians and the Akkadians throughout Mesopotamia, which included widespread bilingualism.[4] The influence of Sumerian on Akkadian (and vice versa) is evident in all areas, from lexical borrowing on a massive scale, to syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence.[4] This has prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and Akkadian in the third millennium as a sprachbund.[4]

Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as the spoken language of Mesopotamia somewhere after the turn of the 3rd and the 2nd millennium BC (the exact dating being a matter of debate),[5] but Sumerian continued to be used as a sacred, ceremonial, literary and scientific language in Mesopotamia until the 1st century AD.

The city of Assur (Ashur) seems to have existed since at least the middle of the third millennium BC, although it appears to have been an administrative centre at this time rather than an independent state. According to some Judaeo-Christian traditions, the city of Ashur (also spelled Assur or Aššur) was founded by Ashur the son of Shem, who was deified by later generations as the city's patron god, however there is absolutely no historical basis whatsoever for this tradition in Mesopotamian annals; Assyrian tradition itself lists an early Assyrian king named Ushpia as having dedicated the first temple to the god Ashur in the city in the 21st century BC, it is not known if he was the first fully independent ruler of Assyria as a city state however, as no records have yet been discovered regarding the earlier kings. It is likely that the city was named in honour of the god of the same name. The upper Tigris River valley seems to have been ruled by Sumerians and later Akkad in early antiquity. The Akkadian Empire of Sargon the Great, which united all the Akkadian speaking Semites, including the Assyrians, claimed to encompass the surrounding "four quarters"; the regions north of the Akkadian homeland had been known as Subartu. The name Azuhinum in Akkadian records also seems to refer to Assyria proper. The Akkadian Empire was destroyed by barbarian Gutian people in 2154 BC, then rebuilt, and ended up being governed as part of the Empire of the Sumerian 3rd dynasty of Ur founded in 2112 BC. The rulers of Assyria during the period between 2154 BC and 2112 BC may have been fully independent as the Gutians are only known to have administered southern Mesopotamia, however there is no information from Assyria bar the king list for this period. Prior to Ushpia, the city of Ashur was a regional administrative center of the Akkadian Empire, implicated by Nuzi tablets,[6] subject to their fellow Akkadian Sargon and his successors.

Old Assyrian Period

Of the early history of the kingdom of Assyria, little is positively known. The Assyrian King List mentions rulers going back to the 23rd and 22nd century BC. The earliest king named Tudiya, who was a contemporary of Ibrium of Ebla, appears to have lived in the 23rd century BC, according to the Assyrian King List. Ibrium concluded a treaty with Tudiya of Assyria for the use of a trading post officially controlled by Ebla. He was succeeded by Adamu and then a further thirteen rulers, about all of whom nothing is yet known. These early kings from the 23rd to late 21st centuries BC, who are recorded as kings who lived in tents were likely to have been Akkadian semi nomadic pasturalist rulers subject to the Akkadian Empire, who dominated the region and at some point during this period became fully urbanised and founded the city state of Ashur.[7]

The first inscriptions of Assyrian rulers appear in the late 21st Century BC. Assyria then consisted of a number of city states and small Semitic Akkadian kingdoms. The foundation of the first true urbanised Assyrian monarchy was traditionally ascribed to Ushpia a contemporary of Ishbi-Erra of Larsa[8] circa 2025 BC. He was succeeded in succession by Apiashal, Sulili, Kikkiya and Akiya of whom nothing is known.

In around 1975 BC Puzur-Ashur I founded a new dynasty, and his successors such as Shalim-ahum, Ilushuma (1945- 1906 BC), Erishum I (1905- 1867 BC), Ikunum (1867- 1860 BC), Sargon I, Naram-Sin and Puzur-Ashur II left inscriptions regarding the building of temples to Ashur, Adad and Ishtar in Assyria. Ilushuma in particular appears to have been a powerful king who made many raids into southern Mesopotamia between 1945 BC and 1906 BC, attacking the independent Sumero-Akkadian city states of the region such as Isin, and founding colonies in Asia Minor. This was to become a pattern throughout the history of ancient Mesopotamia with the future rivalry between Assyria and Babylonia. However, Babylonia did not exist at this time, but was founded in 1894 BC by an Amorite prince named Sumuabum during the reign of Erishum I. The Amorites had overrun southern Mesopotamia from the mid 20th century BC, deposing native Sumero-Akkadian dynasties and setting up their own kingdoms, but were repelled by the Assyrian kings of the 20th and 19th centuries BC.

Assyria had extensive contact with cities on the Anatolian plateau in Asia Minor. The Assyrians established colonies in Cappadocia, (e.g., at Kanesh (modern Kültepe) from 1920 BC to 1740 BC. These colonies, called karum, the Akkadian word for 'port', were attached to Anatolian cities, but physically separate, and had special tax status. They must have arisen from a long tradition of trade between Assyria and the Anatolian cities, but no archaeological or written records show this. The trade consisted of metal (perhaps lead or tin; the terminology here is not entirely clear) and textiles from Assyria, that were traded for precious metals in Anatolia.

Like many city-states in Mesopotamian history, Ashur was, to a great extent, an oligarchy rather than a monarchy. Authority was considered to lie with "the City", and the polity had three main centres of power — an assembly of elders, a hereditary ruler, and an eponym. The ruler presided over the assembly and carried out its decisions. He was not referred to with the usual Akkadian term for "king", šarrum; that was instead reserved for the city's patron deity Assur, of whom the ruler was the high priest. The ruler himself was only designated as "the steward of Assur" (iššiak Assur), where the term for steward is a borrowing from Sumerian ensi(k). The third centre of power was the eponym (limmum), who gave the year his name, similarly to the archons and consuls of Classical Antiquity. He was annually elected by lot and was responsible for the economic administration of the city, which included the power to detain people and confiscate property. The institution of the eponym as well as the formula iššiak Assur lingered on as ceremonial vestiges of this early system throughout the history of the Assyrian monarchy.[9]

Empire of Shamshi-Adad I

In 1813 BC the native Akkadian king of Assyria Erishum II (1819- 1813 BC) was deposed, and the throne of Assyria was usurped by Shamshi-Adad I (1813 BC – 1791 BC) in the expansion of Amorite tribes from the Khabur River delta. Although regarded as an Amorite, Shamshi-Adad is credited with decendancy from the native ruler Ushpia in the Assyrian King List. He put his son Ishme-Dagan on the throne of a nearby Assyrian city, Ekallatum, and maintained Assyria's Anatolian colonies. Shamshi-Adad I then went on to conquer the kingdom of Mari on the Euphrates putting another of his sons, Yasmah-Adad on the throne there. Shamshi-Adad's Assyria now encompassed the whole of northern Mesopotamia and included territory in Asia Minor and northern Syria. He himself resided in a new capital city founded in the Khabur valley, called Shubat-Enlil.

Ishme-Dagan inherited Assyria, but Yasmah-Adad was overthrown by a new king called Zimrilim in Mari. The new king of Mari allied himself with king Hammurabi, who had made the recently created, and originally minor state of Babylon a major power. Hammurabi was also an Amorite. Assyria now faced the rising power of Babylon in the south. Ishme-Dagan responded by making an alliance with the enemies of Babylon, and the power struggle continued without resolution for decades. Ishme-Dagan, like his father was a great warrior, and in addition to repelling Babylonian attacks, campaigned successfully against the Turukku in Ekallatum (successors of the Gutians and Lullubi), and against Dadusha, king of Eshnunna and Iamhad (modern Aleppo)

Assyria under Babylonian domination

Hammurabi after first conquering Mari, Larsa and Eshnunna eventually prevailed over Ishme-Dagan's successors, and conquered Assyria for Babylon in 1756 BC. With Hammurabi, the various karum colonies in Anatolia ceased trade activity — probably because the goods of Assyria were now being traded with the Babylonians. The Assyrian monarchy survived, however the three Amorite kings succeeding Ishme-Dagan; Mut-Ashkur (who was the son of Ishme-Dagan and married to a Hurrian queen), Rimush and Asinum were vassals, dependent on the Babylonians for a few decades.

Assyrian independence

Babylonia seems to have lost control over Assyria during the reign of Hammurabi's successor Samsu-iluna. A period of civil war ensued after the deposition of the Amorite vassal king of Assyria Asinum, who was a grandson of Shamshi-Adad I, by a native Akkadian vice regent named Puzur-Sin. A native Akkadian king Ashur-dugul seized the throne, and a period of civil war ensued with five further kings (Ashur-apla-idi, Nasir-Sin, Sin-namir, Ipqi-Ishtar and Adad-salulu) all reigning in quick succession. Babylonia seems to have been too powerless to intervene. Finally, a native Akkadian king named Adasi came to the fore circa 1720 BC and completely freed Assyria from the pretence of Babylonian dominance. This also brought to an end the Amorite presence in Assyria, although they were to remain in power in Babylon until 1595 BC. Adasi drove the Babylonians and Amorites from northern Mesopotamia during the late 18th century BC and Babylonian power began to quickly wane in Mesopotamia as a whole.

Adasi was succeeded by Bel-bani (1700-1691 BC). Little is known of many of the kings that followed such as; Libaya (1690-1674 BC), Sharma-Adad I (1673-1662 BC), Iptar-Sin (1661-1650 BC), Bazaya (1649-1622 BC), Lullaya (1621-1618 BC), Shu-Ninua (1615-1602 BC), Sharma-Adad II (1601-1599 BC), Erishum III (1598-1586 BC), and Shamshi-Adad II (1585-1580 BC). However Assyria seems to have been a relatively strong and stable nation, existing undisturbed by its neighbours such as the Hittites, Hurrians, Amorites, Babylonians or Mitanni for well over 200 years. When Babylon fell to the Kassites in 1595 BC, they were unable to make inroads into Assyria and there seems to have been no trouble between the first Kassite ruler of Babylon, Agum II and Erishum III of Assyria, and a treaty was signed between the two rulers. Similarly, Adad-nirari I (1547-1522 BC) seems not to have been troubled by the newly founded Mitanni kingdom, the Hittite empire or Babylon during his 25 year reign. Puzur-Ashur III (1521-1498 BC) of Assyria and Burna-Buriash I the Kassite king of Babylon, signed a treaty defining the borders of the two nations in the late 16th nation century BC. Puzur-Ashur III, undertook much rebuilding work in Assur, the city was refortified and the southern quarters incorporated into the main city defences. Temples to the moon god Sin (Nanna) and the sun god Shamash were erected in the 15th century BC.

Assyria under Mitanni domination

However the emergence of the Mitanni Empire in the 16th century BC did eventually lead to a period of Mitanni-Hurrian domination in the 15th Century. Some time after the death of the capable Puzur-Ashur III in 1498 BC, Saushtatar, king of Hanilgalbat (Hurrians of Mitanni), sacked Ashur and made Assyria a largely vassal state. This event is most likely to have happened during the reign of Enlil-nasir I or his successor Nur-ili. The Mitanni appear not to have interfered in Assyrian internal affairs, for example the son of Nur-ili, Ashur-shaduni was deposed by his uncle Ashur-rabi I and similarly, Ashur-nadin-ahhe I was deposed by his own brother Enlil-nasir II in 1420 BC. Assyrian kings seemed to have been free of this dominance regarding international affairs at times also, as evidenced by the treaty between Ashur-bel-nisheshu and Karaindash of Babylon in the late 15th century. By the reign of Eriba-Adad I (1392 BC - 1366 BC) Mitanni influence over Assyria was on the wane. Eriba-Adad I became involved in a dynastic battle between Tushratta and his brother Artatama II and after this his son Shuttarna II, who called himself king of the Hurri while seeking support from the Assyrians. A pro-Hurri/Assyria faction appeared at the royal Mitanni court, which his son and successor Ashur-uballit I would take advantage of.

There are dozens of Mesopotamian cuneiform texts from this period, with precise observations of solar and lunar eclipses, that have been used as 'anchors' in the various attempts to define the chronology of Babylonia and Assyria for the early second millennium (i.e., the "high", "middle", and "low" chronologies.)

Middle Assyrian period — Assyrian resurgence

Scholars variously date the beginning of the "Middle Assyrian period" to either the fall of the Old Assyrian kingdom of Shamshi-Adad I, or to the ascension of Ashur-uballit I to the throne of Assyria.

Assyrian expansion and empire

Eriba-Adad I had loosened Mitanni influence over Assyria and in turn made Assyria an influence on Mitanni affairs, and influence over Assyria collapsed completely during the reign of Ashur-uballit I (1365 BC – 1330 BC). Assyrian pressure from the east and Hittite pressure from the north-west, enabled Ashur-uballit I to completely throw off any remaining Mitanni influence and again make Assyria a fully independent and indeed imperial power at the expense of Kassite Babylonia, the Mitanni themselves, Hurrians and the Hittites; and a time came when the Kassite king in Babylon was glad to marry the daughter of Ashur-uballit, whose letters to Akhenaten of Egypt form part of the Amarna letters. This marriage led to disastrous results, as the Kassite faction at court murdered the Babylonian king and placed a pretender on the throne. Assur-uballit promptly invaded Babylonia to avenge his son-in-law, entering Babylon, deposing the king and installing Kurigalzu II of the royal line king there. Ashur-uballit I then attacked and defeated Mattiwaza the Mitanni king despite attempts by the Hittite king Suppiluliumas, now fearful of growing Assyrian power, attempting to preserve his throne with military support. The lands of the Mitanni and Hurrians were duly appropriated by Assyria, making it a large and powerful empire.

Enlil-nirari (1329- 1308 BC) succeeded Ashur-uballit I. He described himself as a "Great-King" (Sharru rabû) in letters to the Hittite kings. He was immediately attacked by Kurigalzu II of Babylon who had been installed by his father, but succeeded in defeating him, repelling Babylonian attempts to invade Assyria, counter attacking and appropriating Babylonian territory in the process, thus further expanding Assyria. The successor of Enlil-nirari, Arik-den-ili (c. 1307-1296 BC), consolidated Assyrian power, and successfully campaigned in the Zagros Mountains to the east, subjugating the Lullubi and Gutians. He was followed by Adad-nirari I who made Kalhu (Biblical Calah) his capital, and continued expansion to the northwest, mainly at the expense of the Hittites and Hurrians, conquering Hittite territories such as Carchemish and beyond. Adad-nirari I made further gains to the south, annexing Babylonian territory and forcing the Kassite rulers of Babylon into accepting a new frontier agreement in Assyria's favour.

In 1274 BC Shalmaneser I ascended the throne. He proved to be a great warrior king. During his reign he conquered the powerful kingdom of Urartu in the Caucasus Mountains and the fierce Gutians of the Zagros Mountains in modern Iran. He then attacked the Mitanni-Hurrians, defeating both King Shattuara and his Hittite and Aramean allies, finally completely destroying the Hurrian kingdom in the process. Assyria was now a large and powerful empire, and a major threat to Egyptian and Hittite interests in the region, and was perhaps the reason that these two powers made peace with one another.[10]

Shalmaneser's son and successor, Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244 BC -1208 BC), conquered Babylonia, deposing Kashtiliash IV and ruled there himself as king for seven years, taking on the old title "King of Sumer and Akkad" first used by Sargon of Akkad. Tukulti-Ninurta I became the first native Mesopotamian to rule the state of Babylonia, its founders having been Amorites, succeeded by Kassites.[11] In the process he defeated the Elamites, who had themselves coveted Babylon.

However, Tukulti-Ninurta I was murdered by his own sons in a palace revolt and was succeeded by Ashur-nadin-apli. Another unstable period for Assyria followed, it was riven by periods of internal strife and the new king only made token and unsuccessful attempts to recapture Babylon, whose Kassite kings had taken advantage of the upheavals in Assyria and freed themselves from Assyrian rule. However, Assyria itself was not threatened by foreign powers during the reigns of Ashur-nirari III, Enlil-kudurri-usur and Ninurta-apal-Ekur (1192- 1180 BC), although Ninurta-apal-Ekur usurped the throne from Enlil-kudurri-usur. Assyria appears to have stabilised by the reign of Ashur-Dan I who ruled for an unusually long period of 46 years, from 1179 BC to 1133 BC. Another brief period of internal upheaval followed the death of Ashur-Dan I when his son and successor Ninurta-tukulti-Ashur was deposed in his first year of rule by his own brother Mutakkil-Nusku and forced to flee to Babylonia which had maintained friendly relations with Ashur-Dan I.

Mutakkil-Nusku himself died in the same year (1133 BC) leaving a third brother Ashur-resh-ishi I (1133 -1116 BC) the throne. This was to lead to a renewed period of Assyrian expansion and empire. As the Hittite empire collapsed from the onslaught of the Phrygians (called Mushki in Assyrian annals), Babylon and Assyria began to vie for Amorite regions (in modern Syria), formerly under firm Hittite control. When their forces encountered one another in this region, the Assyrian king Ashur-resh-ishi I met and defeated Nebuchadnezzar I of Babylon on a number of occasions. Assyria then invaded and annexed Hittite controlled lands in Asia Minor and Aram (Syria), making it once more an imperial power.

Tiglath-Pileser I (1115- 1077 BC), vies with Shamshi-Adad I and Ashur-uballit I among historians as being regarded as the founder of the first Assyrian empire. The son of Ashur-resh-ishi I, he ascended to the throne upon his fathers death, and became one of the greatest of Assyrian conquerors during his 38 year reign.[12]

His first campaign in 1112 BC was against the Phrygians who had attempted to occupy certain Assyrian districts in the Upper Euphrates; after driving outh the Phrygians he then overran the Luwian kingdoms of Commagene, Cilicia and Cappadocia, and drove the Hittites from the Assyrian province of Subartu, northeast of Malatia.

In a subsequent campaign, the Assyrian forces penetrated Urartu, into the mountains south of Lake Van and then turned westward to receive the submission of Malatia. In his fifth year, Tiglath-Pileser attacked Commagene, Cilicia and Cappadocia, and placed a record of his victories engraved on copper plates in a fortress he built to secure his Cilician conquests.

The Aramaeans of northern Syria were the next targets of the Assyrian king, who made his way as far as the sources of the Tigris.[12] The control of the high road to the Mediterranean was secured by the possession of the Hittite town of Pethor at the junction between the Euphrates and Sajur; thence he proceeded to conquer the Canaanite/Phoenician cities of (Byblos), Sidon, and finally Arvad where he embarked onto a ship to sail the Mediterranean, on which he killed a nahiru or "sea-horse" (which A. Leo Oppenheim translates as a narwhal) in the sea.[12] He was passionately fond of hunting and was also a great builder. The general view is that the restoration of the temple of the gods Ashur and Hadad at the Assyrian capital of Assur (Ashur) was one of his initiatives.[12] He also invaded and defeated Babylon twice, assuming the old title "King of Sumer and Akkad", forcing tribute from Babylon, although he did not actually depose the actual king in Babylonia, where the old Kassite Dynasty had now succumbed to an Elamite one.

Assyria in the Ancient Dark Ages

After Tiglath-Pileser I died in 1076 BC, Assyria was in comparative decline for the next 150 years. The period from 1200 BC to 900 BC was a dark age for the entire Near East, North Africa, Caucasus, Mediterranean and Balkan regions, with great upheavals and mass movements of people. Despite the apparent weakness of Assyria, at heart it in fact remained a solid, well defended nation whose warriors were the best in the world. Assyria, with its stable monarchy and secure borders was in a stronger position during this time than potential rivals such as Egypt, Babylonia, Elam, Phrygia, Urartu, Persia and Media[13] Kings such as Ashur-bel-kala, Eriba-Adad II, Ashur-rabi II, Ashurnasirpal I, Tiglath-Pileser II and Ashur-Dan II successfully defended Assyria's borders and upheld stability during this tumultuous time. Ashur-Dan II is recorded as having made punitive raids outside the borders of Assyria to clear Aramean and other tribal peoples from the regions surrounding Assyria, this appears to have been the policy of Assyrian kings during this period. This long period of isolation ended with the accession in 911 BC of Adad-nirari II.

Society in the Middle Assyrian period

Assyria had difficulties with keeping the trade routes open. Unlike the situation in the Old Assyrian period, the Anatolian metal trade was effectively dominated by the Hittites and the Hurrians. These people now controlled the Mediterranean ports, while the Kassites controlled the river route south to the Persian Gulf.

The Middle Assyrian kingdom was well organized, and in the firm control of the king, who also functioned as the High Priest of Ashur, the state god. He had certain obligations to fulfill in the cult, and had to provide resources for the temples. The priesthood became a major power in Assyrian society. Conflicts with the priesthood are thought to have been behind the murder of king Tukulti-Ninurta I.

The main Assyrian cities of the middle period were Ashur, Kalhu (Nimrud) and Nineveh, all situated in the Tigris River valley. At the end of the Bronze Age, Nineveh was much smaller than Babylon, but still one of the world's major cities (population ca. 33,000). By the end of the Neo-Assyrian period, it had grown to a population of some 120,000, and was possibly the largest city in the world at that time.[14] All free male citizens were obliged to serve in the army for a time, a system which was called the ilku-service. The Assyrian law code, notable for its repressive attitude towards women in their society, was compiled during this period.

Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire is usually considered to have begun with the accession of Adad-nirari II, in 911 BC, lasting until the fall of Nineveh at the hands of the Babylonians, Medes, Scythians and Cimmerians in 612 BC.[15]

In the Old and Middle Assyrian periods, Assyria had at times been a strong kingdom and imperial power based in northern Mesopotamia, competing for dominance with Babylonia to the south and with the Hittites and Arameans to the west, the Hittite empire and the Phrygians to the north, and the Elamites to the east. Beginning with the campaigns of Adad-nirari II (911-882 BC), Assyria once more became a great power, growing to be the greatest empire the world had yet seen. He firmly subjugated the areas previously under only nominal Assyrian vassalage, conquering and deporting troublesome Aramean, neo Hittite and Hurrian populations in the north to far-off places. Adadinirari II then twice attacked and defeated Shamash-mudammiq of Babylonia, annexing a large area of land north of the Diyala River and the towns of Hīt and Zanqu in mid Mesopotamia. He made further gains over Babylonia under Nabu-shuma-ukin later in his reign.

His successor, Tukulti-Ninurta II (891-884 BC) consolidated Assyria's gains and expanded into the Zagros Mountains in modern Iran, subjugating the newly arrived Persians and Medes as well as pushing into central Asia Minor.

Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) was a fierce and ruthless ruler who advanced without opposition through Aram (modern Syria) and Asia Minor as far as the Mediterranean and conquered and exacted tribute from Aramea, Phrygia and Phoenicia among others. Ashurnasirpal II also repressed revolts among the Medes and Persians in the Zagros Mountains, and moved his capital to the city of Kalhu (Calah/Nimrud). The palaces, temples and other buildings raised by him bear witness to a considerable development of wealth, science, architecture and art. He also built a number of new towns, such as Imgur-Enlil (Balawat).

Shalmaneser III (858–823 BC) attacked and reduced Babylonia to vassalage, and defeated Aramea, Israel, Urartu, Phoenicia and the neo Hittite states, forcing all of these to pay tribute to Assyria. He consolidated Assyrian control over the regions conquered by his predecessors. Shamshi-Adad V (822-811 BC) inherited an empire beset by civil war which he took most of his reign to quell. He was succeeded by Adad-nirari III who was merely a boy. The Empire was thus ruled by the famed queen Semiramis until 806 BC. Semiramis appears to have campaigned successfully against the Persians and Medes during her regency, leading to the later myths and legends surrounding her.[16] In that year Adad-nirari III took the reins of power. He invaded the Levant and subjugated the Arameans, Phoenicians, Philistines, Israelites, neo Hittites, Moabites and Edomites. He entered Damascus and forced tribute upon its king Ben-Hadad III. He next turned eastward to Iran, and subjugated the Persians, Medes and Manneans, penetrating as far as the Caspian Sea. He then turned south, forcing Babylonia to pay tribute. His next targets were the Chaldean and Sutu tribes of the far south eastern corner of Mesopotamia, whom he conquered and reduced to vassalage, and the Arabs of the deserts to the south of Mesopotamia were forced to pay tribute also.

Adad-nirari III died prematurely in 782 BC and this led to a temporary period of stagnation within the empire. Shalmaneser IV (782 - 773 BC) seems to have wielded little authority, and a victory over Argishti I, king of Urartu at Til Barsip is accredited to an Assyrian General ('Turtanu') named Shamshi-ilu who does not even bother to mention his king. Shamshi-ilu also scored victories over the Arameans and neo Hittites, and again, takes personal credit at the expense of his king. Ashur-dan III ascended the throne in 772 BC. He proved to be a largely ineffectual ruler who was beset by internal rebellions in the cities Ashur, Arrapkha and Guzana. He failed to make further gains in Babylonia and Aram (Syria). His reign was also marred by Plague and an ominous Solar Eclipse. Ashur-nirari V became king in 754 BC, his reign seems to have been one of permanent revolution, and he apprears to have barely left his palace in Nineveh apart from a successful campaign in Asia Minor in 750 BC, until he was deposed by Tiglath-pileser III in 745 BC bringing a resurgence to Assyria.

Tiglath-Pileser III (745-727 BC) initiated a renewed period of Assyrian expansion; Urartu, Persia, Media, Mannea, Babylonia, Arabia, Phoenicia, Israel, Judah, Samaria, Palestine, Nabatea, Chaldea and the Neo-Hittites were subjugated, Tiglath-Pileser III was declared king in Babylon and the Assyrian empire was now stretched from the Caucasus Mountains to Arabia and from the Caspian Sea to Cyprus.

Shalmaneser V (726-723 BC) consolidated Assyrian power during his short reign, and repressed Egyptian attempts to gain a foothold in the near east. Tiglath-Pileser III introduced eastern Aramaic as the Lingua Franca of Assyria and its vast empire.[17]

Sargon II (722-705 BC) maintained the empire, driving the Cimmerians and Scythians from Iran, where they had invaded and attacked the Persians who were vassals of Assyria. Mannea, Cilicia Cappadocia and Commagene were conquered, Urartu was ravaged, and Babylon, Aram, Phoenicia, Israel, Arabia, Phrygia and Cyprus were forced to pay tribute. Sargon II was killed in 705 BC while on a punitive raid against the Cimmerians and was succeeded by Sennacherib.

Sennacherib (705-681 BC), a ruthless ruler, defeated the Greeks who were attempting to gain a foothold in Cilicia, and defeated and drove the Egyptians from Israel and Phoenicia where they had fomented revolt against Assyria. Babylon revolted, and Sennacherib laid waste to the city, defeating its Elamite and Chaldean allies in the process. He then sacked Israel and laid siege to Judah. He installed his own son Ashur-nadin-shumi as king in Babylonia. He maintained Assyrian domination over the Medes, Manneans and Persians to the east, Asia Minor to the north and north west, and the Levant, Phonecia and Aram in the west. Sennacherib was murdered by his own sons in a palace revolt, apparently in revenge for the destruction of Babylon.

Esarhaddon (680-669 BC) expanded Assyria still further, campaigning deep into the Caucasus Mountains in the north, breaking Urartu completely in the process. Tiring of Egyptian interference in the Assyrian Empire, Esarhaddon crossed the Sinai Desert, and invaded and conquered Egypt, driving its foreign Nubian/Kushite and Ethiopian rulers out in the process. He expanded the empire as far south as Arabia and Dilmun (modern Bahrain or Qatar). Esarhaddon also completely rebuilt Babylon during his reign, bringing peace to Mesopotamia as a whole. The Babylonians, Egyptians, Elamites, Cimmerians, Scythians, Persians, Medes, Manneans, Arameans, Chaldeans, Israelites, Phonecians and Urartu were vanquished and regarded as vassals and Assyria's empire was kept secure. Esarhaddon died whilst on route to Egypt to put down a revolt among the native dynasty he had installed.

Under Ashurbanipal (669-627 BC) its domination spanned from from the Caucasus Mountains in the north to Nubia, Egypt and Arabia in the south, and from Cyprus and Antioch in the west to Persia in the east. Ashurbanipal destroyed Elam and smashed a rebellion led by his own brother Shamash-shum-ukin who was the Assyrian king of Babylon, exacting savage revenge on the coalition of Chaldeans, Nabateans, Arameans, Sutu, Arabs and Elamites who had supported him. An Assyrian governor named Kandalanu was the installed to rule Babylonia on Ashurbanipal's behalf. Persia and Media were regarded as vassals of Ashurbanipal. He built vast libraries and initiated a surge in the building of temples and palaces.

At its height Assyria conquered the 25th dynasty Egypt (and expelled its Nubian/Kushite dynasty) as well as Babylonia, Chaldea, Elam, Media, Persia, Ararat (Armenia), Phoenicia, Aramea/Syria, Phrygia, the Neo-Hittites, Hurrians, northern Arabia, Gutium, Israel, Judah, Moab, Edom, Corduene, Cilicia, Mannea and parts of Ancient Greece (such as Cyprus), and defeated and/or exacted tribute from Scythia, Cimmeria, Lydia, Nubia, Ethiopia and others.

Downfall, 626-605 BC

Assyria was severely crippled following the death of Ashurbanipal in 627 BC — the nation descending into a prolonged and brutal series of civil wars involving three rival kings, Ashur-etil-ilani, Sin-shumu-lishir and Sin-shar-ishkun.

Ashur-etil-ilani was deposed in 620 BC, after four years of bitter fighting by Sin-shumu-lishir, an Assyrian general also briefly occupied and claimed the throne of Babylon in that year. In turn, Sin-shumu-lishir was deposed after a year of warfare by Sin-shar-ishkun — who was then himself faced with constant rebellion in the Assyrian homeland, coupled with wholesale revolution in Babylon and aggression from former Assyrian colonies to the east and north. Many of Assyria's vassal states and colonies took advantage of this situation to free themselves from Assyrian rule.

By 620 BC, Nabopolassar, a member of the Chaldean tribe from the far southeast of Mesopotamia, had claimed Babylonia in the confusion. Sin-shar-ishkun amassed a large army to eject Nabopolassar from Babylon, however yet another revolt broke out in Assyria, forcing the bulk of his army to turn back, where they promptly joined the rebels in Nineveh; similarly, Nabopolassar was unable to make any inroads into Assyria despite its weakened state, being repelled at every attempt. However, Nabopolassar entered into an alliance with the Median king Cyaxares, who had taken advantage of the upheavals in Assyria to free his people from Assyrian vassalage and unite the Iranic Medes and Persians, and the remnants of the Elamites and Manneans, into a powerful Median-dominated force. The Babylonians and Medes, together with the Scythians and Cimmerians, attacked Assyria in 616 BC. After four years of bitter fighting, Nineveh was finally sacked in 612 BC, after a prolonged siege followed by house to house fighting, Sin-shar-ishkun was killed in the process. However Assyrian resistance continued, Ashur-uballit II (612- 605 BC) took the throne, won a few battles, and occupied and held out at Harran from 612 BC until 609 BC when he was eventually overrun by the Babylonians and Medes. The Egyptians then belatedly came to Assyria's aid, Ashur-uballit II and Necho of Egypt made a failed attempt to recapture Harran, and the next three years saw the Egyptians and the remnants of the Assyrian army vainly attempting to eject the invaders from Assyria. Final resistance seems to have ended in 605 BC, with the defeat of an Assyrian-Egyptian relief force at Carchemish. It is not known whether Ashur-uballit II perished at Harran, Carchemish, continued to fight on, or simply disappeared into obscurity.

Assyria after the Empire

Assyria was ruled by Babylon from 605 BC until 539 BC, and in a twist of fate, Nabonidus the last king of Babylon was himself an Assyrian from Harran; however apart from plans to dedicate religious temples in that city, Nabonidus showed little interest in rebuilding Assyria. Nineveh and Kalhu remained in ruins, conversely a number of towns and cities such as Arrapkha, Guzana and Harran remained intact, and Assur and Arbela were not completely destroyed, as is attested by their later revival. However, Assyria spent much of this period in a state of devastation following its fall. After this, it was ruled by the Persian Achaemenid Empire (as Athura) from 539 BC to 330 BC. Assyria seems to have recovered somewhat, and flourished during this period. It became a major agricultural and administrative centre of the Achaemenid Empire, and its soldiers were a mainstay of the Persian Army.[18] In fact Assyria even became powerful enough to raise a full scale revolt against the empire in 520 BC. The Persians had spent centuries under Assyrian domination, and Assyrian influence can be seen in Achaemenid art, infrastructure and administration. Early Persian rulers saw themselves as successors to Ashurbanipal, and Mesopotamian Aramaic was retained as the lingua franca of the empire for over two hundred years.[19] In 330 BC, Assyria fell to Alexander the Great, the Macedonian Emperor from Greece; it thereafter became part of the Seleucid Empire and was renamed Syria, a Hurrian, Luwian and Greek corruption of Assyria.[20] It is from this period that the later Syria Vs Assyria naming controversy arises, the Seleucids applied the name to Assyria itself but also to the lands to the west which had been part of the Assyrian empire. When they lost control of Assyria itself, the name Syria survived and was applied to the land of Aramea to the west, that had once been part of the Assyrian empire. This was to lead to both the Assyrians from Mesopotamia and Arameans from the Levant being dubbed Syrians in Greco-Roman culture. By 150 BC, it was under the control of the Parthian Empire as Athura where the Assyrian city of Ashur seems to have gained a degree of autonomy, and temples to the native gods of Assyria were resurrected. A number of neo-Assyrian states arose, namely Adiabene, Osroene and Hatra. In 116 AD, under Trajan, it was taken over by Rome as the Roman Province of Assyria. The Assyrians began to convert to Christianity from Ashurism during the period between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD. Romans and Parthians fought over Assyria and the rest of Mesopotamia until 226 AD, when it was taken over by the Sassanid (Persian) Empire. It was known as Asuristan during this period, and became a main centre of the Church of the East (now the Assyrian Church of the East), with a flourishing Syriac (Assyrian) Christian culture which exists there to this day. Temples were still being dedicated to the national god Ashur in his home city and in Harran during the 4th century AD, indicating an Assyrian identity was still strong. After the Arab Islamic conquest in the 7th Century AD Assyria was dissolved as an entity. Under Arab rule Mesopotamia as a whole underwent a process of Arabisation and Islamification, and the region saw a large influx of non indigenous Arabs, Kurds, and later Turkic peoples. However a percentage of the indigenous Assyrian population (known as Ashuriyun by the Arabs) resisted this process, Assyrian Aramaic language and Church of the East Christianity were still dominant in the north, as late as the 11th and 12th centuries AD.[21] The city of Assur was occupied by Assyrians during the islamic period until the 14th century when Tamurlane conducted a massacre of indigenous Assyrian Christians. After that there are no traces of a settlement in the archaeological and numismatic record. [2]. The massacres by Tamurlane massively reduced the Assyrian population throughout Mesopotamia. An Assyrian war of independence was fought during World War I following the Assyrian Genocide suffered at the hands of the Ottomans and their Kurdish allies. Further persecutions have occurred since, such as the Simele Massacre, al Anfal campaign and Baathist and Islamist persecutions.

Language

During the third millennium BC, there developed a very intimate cultural symbiosis between the Sumerians and the Akkadians, which included widespread bilingualism.[4] The influence of Sumerian on Akkadian (and vice versa) is evident in all areas, from lexical borrowing on a massive scale, to syntactic, morphological, and phonological convergence.[4] This has prompted scholars to refer to Sumerian and Akkadian in the third millennium as a sprachbund.[4]

Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as the spoken language of Mesopotamia somewhere around the turn of the 3rd and the 2nd millennium BC (the exact dating being a matter of debate),[5] but Sumerian continued to be used as a sacred, ceremonial, literary and scientific language in Mesopotamia until the 1st century AD.

In ancient times Assyrians spoke a dialect of the Akkadian language, an eastern branch of the Semitic languages. The first inscriptions, called Old Assyrian (OA), were made in the Old Assyrian period. In the Neo-Assyrian period the Aramaic language became increasingly common, more so than Akkadian — this was thought to be largely due to the mass deportations undertaken by Assyrian kings, in which large Aramaic-speaking populations, conquered by the Assyrians, were relocated to Assyria and interbred with the Assyrians. The ancient Assyrians also used the Sumerian language in their literature and liturgy, although to a more limited extent in the Middle- and Neo-Assyrian periods, when Akkadian became the main literary language.

The destruction of the Assyrian capitals of Nineveh and Assur by the Babylonians, Medes and their allies ensured that much of the bilingual elite were wiped out. By the 7th century BC, much of the Assyrian population used Eastern Aramaic and not Akkadian. The last Akkadian inscriptions in Mesopotamia date from the 1st Century AD. However Eastern Aramaic dialects still survive to this day among Assyrians in the regions of northern Iraq, southeast Turkey, northwest Iran and northeast Syria that constituted old Assyria.

After 90 years of effort, the University of Chicago has published an Assyrian Dictionary, whose form is more encyclopedia in style than dictionary.[22]

Arts and sciences

Assyrian art preserved to the present day predominantly dates to the Neo-Assyrian period. Art depicting battle scenes, and occasionally the impaling of whole villages in gory detail, was intended to show the power of the emperor, and was generally made for propaganda purposes. These stone reliefs lined the walls in the royal palaces where foreigners were received by the king. Other stone reliefs depict the king with different deities and conducting religious ceremonies. Many stone reliefs were discovered in the royal palaces at Nimrud (Kalhu) and Khorsabad (Dur-Sharrukin). A rare discovery of metal plates belonging to wooden doors was made at Balawat (Imgur-Enlil).

Assyrian sculpture reached a high level of refinement in the Neo-Assyrian period. One prominent example is the winged bull Lamassu, or shedu that guard the entrances to the king's court. These were apotropaic meaning they were intended to ward off evil. C. W. Ceram states in The March of Archaeology that lamassi were typically sculpted with five legs so that four legs were always visible, whether the image were viewed frontally or in profile.

Since works of precious gems and metals usually do not survive the ravages of time, we are lucky to have some fine pieces of Assyrian jewelry. These were found in royal tombs at Nimrud.

There is ongoing discussion among academics over the nature of the Nimrud lens, a piece of quartz unearthed by Austen Henry Layard in 1850, in the Nimrud palace complex in northern Iraq. A small minority believe that it is evidence for the existence of ancient Assyrian telescopes, which could explain the great accuracy of Assyrian astronomy. Other suggestions include its use as a magnifying glass for jewellers, or as a decorative furniture inlay. The Nimrud Lens is held in the British Museum.[23]

The Assyrians were also innovative in military technology with the use of heavy cavalry, sappers, siege engines etc.

Legacy and rediscovery

Achaemenid Assyria (539 BC - 330 BC) retained a separate identity (Athura), official correspondence being in Imperial Aramaic, and there was even a determined revolt of the two Assyrian provinces of Mada and Athura in 520 BC. Under Seleucid rule (330 BC — Approx 150 BC), however, Aramaic gave way to Greek as the official administrative language. Aramaic was marginalised as an official language, but remained spoken in both Assyria and Babylonia by the general populace. It also remained the spoken tongue of the indigenous Assyrian/Babylonian citizens of all Mesopotamia under Persian, Greek and Roman rule, and indeed well into the Arab period it was still the language of the majority, particularly in the north of Mesopotamia, surviving to this day among the Assyrian Christians.

Between 150 BC and 226 AD Assyria changed hands between the Parthians and Romans Roman Province of Assyria until coming under the rule of Sassanid Persia in 226 AD - 651 AD, where it was known as Asuristan.

A number of at least partly neo Assyrian kingdoms existed in the area between in the late classical and early Christian period also; Adiabene, Hatra and Osroene.

Classical historiographers had only retained a very dim picture of Assyria. It was remembered that there had been an Assyrian empire predating the Persian one, but all particulars were lost. Thus Jerome's Chronicon lists 36 kings of the Assyrians, beginning with Ninus, son of Belus, down to Sardanapalus, the last king of the Assyrians before the empire fell to Arbaces the Median. Almost none of these have been substantiated as historical, with the exception of the Neo-Assyrian and Babylonian rulers listed in Ptolemy's Canon, beginning with Nabonassar.

The modern discovery of Babylonia and Assyria begins with excavations in Nineveh in 1845, which revealed the Library of Ashurbanipal. Decipherment of cuneiform was a formidable task that took more than a decade, but by 1857, the Royal Asiatic Society was convinced that reliable reading of cuneiform texts was possible. Assyriology has since pieced together the formerly largely forgotten history of Mesopotamia. In the wake of the archaeological and philological rediscovery of ancient Assyria, Assyrian nationalism became increasingly popular among the surviving remnants of the Assyrian people, and has come to strongly identify with ancient Assyria.

See also

- Assyrian eclipse

- Babylonia and Assyria

- Chaldo-Assyrians

- Geography of Babylonia and Assyria

- List of Assyrians

- List of Assyrian settlements

- List of Assyrian tribes

- Names of Syriac Christians

Notes and references

- ^ Saggs, The Might That Was Assyria, pp. 290, “The destruction of the Assyrian empire did not wipe out its population. They were predominantly peasant farmers, and since Assyria contains some of the best wheat land in the Near East, descendants of the Assyrian peasants would, as opportunity permitted, build new villages over the old cities and carry on with agricultural life, remembering traditions of the former cities. After seven or eight centuries and various vicissitudes, these people became Christians.

- ^ "Parpola identity_article" (PDF). Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ Georges Roux- Ancient Iraq

- ^ a b c d e f Deutscher, Guy (2007). Syntactic Change in Akkadian: The Evolution of Sentential Complementation. Oxford University Press US. pp. 20–21. ISBN 9780199532223. Cite error: The named reference "Deutscher" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b [Woods C. 2006 “Bilingualism, Scribal Learning, and the Death of Sumerian”. In S.L. Sanders (ed) Margins of Writing, Origins of Culture: 91-120 Chicago [1] Cite error: The named reference "woods" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Malati J. Shendge (1 January 1997). The language of the Harappans: from Akkadian to Sanskrit. Abhinav Publications. p. 46. ISBN 9788170173250. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ Georges Roux - Ancient Iraq

- ^ According to the Assyrian King List and Georges Roux-Ancient Iraq

- ^ Larsen, Mogens Trolle (2000): The old Assyrian city-state. In Hansen, Mogens Herman, A comparative study of thirty city-state cultures : an investigation / conducted by the Copenhagen Polis Centre. P.77-89

- ^ Georges Roux - Ancient Iraq

- ^ George Roux- Ancient Iraq

- ^ a b c d The encyclopædia britannica:a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information, Volume 26, Edited by Hugh Chrisholm, 1911, p. 968

- ^ According to George Roux p282-283.

- ^ see historical urban community sizes. Estimates are those of Chandler (1987).

- ^ Chart of World Kingdoms, Nations and Empires — All Empires[dead link]

- ^ Georges Roux- Ancient Iraq

- ^ Ancient Iraq - George Roux

- ^ "Assyrians after Assyria". Nineveh.com. 4 September 1999. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ Georges Roux-Ancient Iraq

- ^ "The Terms "Assyria" and "Syria" Again" (PDF). Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ According to George Roux and Simo Parpola

- ^ "Ancient world dictionary finished — after 90 years". News.yahoo.com. Associated Press. 4 June 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ Lens, British Museum.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

Literature

- Ascalone, Enrico. Mesopotamia: Assyrians, Sumerians, Babylonians (Dictionaries of Civilizations; 1). Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007 (paperback, ISBN 0-520-25266-7).

- Grayson, Albert Kirk: Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles (ABC), Locust Valley, N.Y.; Augustin (1975), Winona Lake, In.; Eisenbrauns (2000).

- Healy, Mark (1991). The Ancient Assyrians. London: Osprey. ISBN 1855321637. OCLC 26351868.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=,|month=,|chapterurl=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help) - Leick, Gwendolyn. Mesopotamia.

- Lloyd, Seton. The Archaeology of Mesopotamia: From the Old Stone Age to the Persian Conquest.

- Rosie Malek-Yonan (2005). The Crimson Field. Pearlida Publishing. ISBN 0977187349. OCLC 2005906414.

- Nardo, Don. The Assyrian Empire.

- Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea. Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia.

- Oppenheim, A. Leo. Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization.

- Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 18 (2).

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=,|laydate=,|laysource=,|quotes=, and|laysummary=(help) - Roux, Georges. Ancient Iraq. Third edition. Penguin Books, 1992 (paperback, ISBN 0-14-012523-X).

- Saggs, H. W. F., The Might That Was Assyria, ISBN 0-283-98961-0

- Virginia Schomp (2005). Ancient Mesopotamia: The Sumerians, Babylonians, and Assyrians. New York: Scholastic Library Pub. ISBN 0531167410. OCLC 60341786.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=,|month=,|chapterurl=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - Spence, Lewis. Myths and Legends of Babylonia and Assyria.

External links

- Assyria on Ancient History Encyclopedia

- Assyrian administrative letters

- "Assyrian Legacy", Prototype Productions (video)

- "Assyria", LookLex Encyclopedia

- Robert William Rogers, The History of Assyria in "btm" format

- Theophilus G. Pinches, The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria in "btm" format

- "The Library at Ninevah", In our Time — BBC Radio 4

- "Assyrians in Arzni-Armenia", Website of the Abovyan city

- Morris Jastrow, Jr., The Civilization of Babylonia and Assyria: its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature, London: Lippincott (1915) — a searchable facsimile at the University of Georgia Libraries; also available in layered PDF format

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.