Australia–East Timor spying scandal

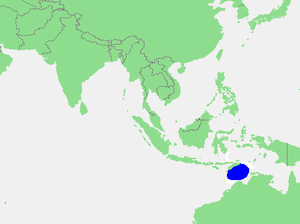

The Australia–East Timor spying scandal began in 2004 when the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) clandestinely planted covert listening devices in a room adjacent to the East Timor (Timor-Leste) Prime Minister's Office at Dili, to obtain information in order to ensure Australia held the upper hand in negotiations with East Timor over the rich oil and gas fields in the Timor Gap.[1] Even though the East Timor government was unaware of the espionage operation undertaken by Australia, negotiations were hostile. The first Prime Minister of East Timor, Mari Alkatiri, bluntly accused the Howard government of plundering the oil and gas in the Timor Sea, stating:

"Timor-Leste loses $1 million a day due to Australia's unlawful exploitation of resources in the disputed area. Timor-Leste cannot be deprived of its rights or territory because of a crime."[2]

Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer responded:

"I think they've made a very big mistake thinking that the best way to handle this negotiation is trying to shame Australia, is mounting abuse on our country...accusing us of being bullying and rich and so on, when you consider all we've done for East Timor."[2]

"Witness K", a former senior ASIS intelligence officer who led the bugging operation, confidentially noted in 2012 the Australian Government had accessed top-secret high-level discussions in Dili and exploited this during negotiations of the Timor Sea Treaty.[3] The treaty was superseded by the signing of the Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS) which restricted further sea claims by East Timor until 2057.[4] Lead negotiator for East Timor, Peter Galbraith, laid out the motives behind the espionage by ASIS:

"What would be the most valuable thing for Australia to learn is what our bottom line is, what we were prepared to settle for. There's another thing that gives you an advantage, you know what the instructions the prime minister has given to the lead negotiator. And finally, if you're able to eavesdrop you'll know about the divisions within the East Timor delegation and there certainly were divisions, different advice being given, so you might be able to lean on one way or another in the course of the negotiations."[2]

Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão found out about the bugging, and in December 2012 told Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard that he knew of the operation and wanted the treaty invalidated as a breach of "good faith" had occurred during the treaty negotiations. Gillard did not agree to invalidate the treaty. The first public allegation about espionage in East Timor in 2004 appeared in 2013 in an official government press release and subsequent interviews by Australian Foreign Minister Bob Carr and Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus. A number of subsequent media reports detailed the alleged espionage.[2]

When the espionage became known, East Timor rejected the Timor Sea treaty, and referred the matter to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague. Timor's lawyers, including Bernard Collaery, intended to call Witness K as a confidential witness in an "in camera" hearing in March 2014. However, in December 2013 the homes and office of both Witness K and his lawyer Bernard Collaery were raided and searched by ASIO and Australian Federal Police, and many legal documents were confiscated. East Timor immediately sought an order from the ICJ for the sealing and return of the documents.[2]

In March 2014, the ICJ ordered Australia to stop spying on East Timor.[5] The Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague considered claims by East Timor over the territory until early 2017, when East Timor dropped the ICJ case against Australia after the Australian Government agreed to renegotiate.[6] In 2018, the parties signed a new agreement which gave 80% of the profits to East Timor and 20% to Australia.

The identity of Witness K has been kept secret under the provisions of the Intelligence Services Act and any person in breach of this could face prosecution.[7]

In June 2018 the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions filed criminal charges against Witness K and his lawyer Bernard Collaery under the National Security Information (NSI) Act which was introduced in 2004 to deal with classified and sensitive material in court cases.[8][9][10] In June 2022, Witness K, who had pleaded guilty, was sentenced to a three-month suspended term of imprisonment and a 12-month good behaviour order.[11] Pre-trial proceedings continued until July 2022, when Collaery's prosecution was discontinued by Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus.[12]

On 9 February 2022 ABC reports that documents filed in court claims that Australia may have been monitoring the phone calls of political leaders in East Timor since 2000.[13]

Background[edit]

In 2002, the Australian Government withdrew from the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) clauses which could bind Australia to a decision of the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague on matters of territorial disputes. Two months later, East Timor officially gained its independence from Indonesia.[3] In 2004, East Timor began negotiating territorial borders with Australia. In response to this, ASIS used an Australian aid project to infiltrate the Palace of Government in Dili and install listening devices in the walls of the cabinet room.[14] This enabled ASIS to obtain top-secret information from treaty negotiators led by Prime Minister Mari Alkatiri. This provided the Australian Government with "an advantage during treaty talks".[3] The installation of listening devices occurred 18 months after the 2002 Bali bombings, during a time of heightened ASIS activity in the Southeast Asia region.[7] In 2006, Australia and East Timor signed the second CMats treaty.[15]

Before the revelations of ASIS's clandestine activities in East Timor, the treaty between East Timor and Australia was ridiculed. Over 50 members of the US Congress sent a letter to Prime Minister John Howard calling for a "fair" and "equitable" resolution of the border dispute, noting East Timor's poverty. Signatories included Nancy Pelosi, Rahm Emanuel and Patrick J. Kennedy.[16] Witness K made the Australian Government's spying activities public after the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security (IGIS) recommended he do so.[17]

David Irvine, ASIS head (2003–2009) authorised the operation. His successor Nick Warner, ASIS head (2009–2017), assisted in an advisory role.[14] Foreign Minister Alexander Downer, who oversaw ASIS was overseas during the operation. According to the lawyer of Witness K, former ACT Attorney-General Bernard Collaery, successive Australian Governments from both major parties have actively sought to cover-up the incident.[14]

Witness K revealed the bugging operation in 2012 after learning Foreign Minister Alexander Downer had become an adviser to Woodside Petroleum, which was benefiting from the treaty.[18]

Reaction to the allegation[edit]

The Gillard government, in response to a letter sent by East Timor's Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão requesting an explanation and a bilateral resolution to the dispute, authorised the installation of listening devices in Collaery's Canberra office.[14] After the story became public in 2012, the Gillard government inflamed tensions with East Timor by denying the alleged facts of the dispute and sending as a representative to Dili someone who was known by Gusmão to have been involved in the bugging.[7] In 2015, Gusmão said of Prime Minister Julia Gillard's response:

"It meant that the Prime Minister of a modern democracy on Timor-Leste's doorstep [Australia] did not know what her intelligence service was doing."[7]

The response of the Gillard government led to East Timor's application to have the case heard in the Permanent Court of Arbitration. According to Gusmão, during a 2014 meeting in Bo'ao, China, Prime Minister Tony Abbott shrugged off East Timor's concerns over the spying scandal by telling Mr. Gusmão not to worry because "[the] Chinese are listening to us".[7] In 2015, the bugging scandal received renewed interest after the Australian Broadcasting Corporation ran a story revealing the level of concern amongst senior intelligence officials in the Australian intelligence apparatus.[7] Attorney-General George Brandis, under lengthy questioning by a panel of Australian senators, admitted that new national security laws could enable prosecution of Witness K and his lawyer, Collaery.[19] Further, Australia's Solicitor General, Justin Gleeson SC, claimed in a submission to the ICJ that Witness K and Collaery could have breached parts of the Criminal Code pertaining to espionage and could be stripped of their Australia citizenship if they are dual-nationals (as, indeed, Collaery is).[19] Foreign Minister Julie Bishop said in April 2016 that: "We stand by the existing treaties, which are fair and consistent with international law."[20]

In August 2016, the Turnbull government indicated it will consider any decision made by the Permanent Court of Arbitration binding. Some[who?] suggested this "softening" was linked to the territorial dispute over the South China Sea between China and neighbouring states.[3][21] The East Timor government continued to press Australia for an equidistant border between the two countries.[22] In 2016, the Australian Labor Party said a new deal could be struck between East Timor and Australia if it formed government.[23]

In September 2016, The Age newspaper in Australia published an editorial claiming East Timor's attempts to resolve this matter in international courts "is an appeal to Australians' sense of fairness".[24]

On 26 September 2016, Labor Foreign Affairs spokesperson Senator Penny Wong said, "In light of this ruling [that the court can hear East Timor's claims], we call on the government to now settle this dispute in fair and permanent terms; it is in both our national interests to do so".[15] To date (March 2018), the Australian Government has not officially acknowledged the spying claims.[25]

"Just as we fought so hard and suffered so much for our independence, Timor-Leste will not rest until we have our sovereign rights over both land and sea," Gusmão, 26 September 2016.[26]

Witness K had his passport seized in 2013. As Collaery has pointed out, such security assessments are usually conducted by ASIO and not, as in the case of Witness K, by ASIS.[14] In 2018, despite having approval from the Director-General of ASIO to apply for a passport, ASIS and the Turnbull government denied Witness K right to obtain a passport citing national security. His lawyer maintained that this was "pure retaliation" and that Witness K remained in "effective house arrest" in Australia.[27]

ASIO raids[edit]

Three months after the election of the Abbott government in 2013, ASIS was authorised by Attorney-General George Brandis to raid the office of Bernard Collaery and the home of Witness K, whose passport was seized.[7][14] Brandis said that he authorised the ASIO raids to protect Australia's national security.[28] Collaery, who represented the East Timorese government in the dispute with the Australian Government over the bugging of cabinet offices during the negotiations for a petroleum and gas treaty in 2004, alleged that two agents from the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) raided his Canberra office and seized his electronic and paper files.[29] The seizing of Witness K's passport prevented him from appearing as a witness in East Timor's case against Australia at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. Collaery said Witness K's ability to travel overseas and appear before The Hague was crucial to East Timor's case.[7]

The passport of Witness K remains confiscated as at April 2020.[30][15][31]

International law[edit]

International Court of Justice[edit]

On 4 March 2014, in response to an East Timorese request for the indication of provisional measures, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ordered Australia not to interfere with communications between East Timor and its legal advisors in the arbitral proceedings and related matters.[32] The case was officially removed from ICJ's case list on 12 June 2015[33] after Timor-Leste confirmed that Australia had handed back its property. The Timor-Leste representative stated that "[f]ollowing the return of the seized documents and data by Australia on 12 May 2015, Timor-Leste [has] successfully achieved the purpose of its Application to the Court, namely the return of Timor-Leste’s rightful property, and therefore implicit recognition by Australia that its actions were in violation of Timor-Leste’s sovereign rights".[34]

Permanent Court of Arbitration[edit]

In 2013, East Timor launched a case at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague to withdraw from a gas treaty that it had signed with Australia on the grounds that ASIS had bugged the East Timorese cabinet room in Dili in 2004.[35]

In April 2016, East Timor began proceedings in the Permanent Court of Arbitration under UNCLOS over the sea border it shares with Australia. The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade released a statement condemning the move, which it said was contrary to the previous treaties it had lawfully signed and implemented. East Timor believed much of the Greater Sunrise oil field fell under its territory and that it had lost $US5 billion to Australian companies as a result of the treaty it was disputing.[20] Hearings before the court commenced on 29 August 2016.[3] The court dismissed Australia's claim that it did not have jurisdiction to hear the case on 26 September 2016.[15]

In early 2017, East Timor withdrew the case against Australia after the Australian Government agreed to renegotiate.[6] In 2018, the parties signed a new agreement that was far more favourable to East Timor which is now expected to reap between 70% and 80% of total revenue.[36]

See also[edit]

- Australia–East Timor relations

- Treaty on Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea

- Australia–Indonesia spying scandal

References[edit]

- ^ "Australia defends East Timor spy row raid". BBC. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Wilkinson, Marian; Cronau, Peter (24 March 2014). "Drawing the Line". Four Corners. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Cannane, Steve (29 August 2016). "East Timor-Australia maritime border dispute set to be negotiated at The Hague". ABC News. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ Robert J. King, "The Timor Gap, 1972-2017", March 2017. Submission No.27 to the inquiry by the Australian Parliament Joint Standing Committee on Treaties into Certain Maritime Arrangements - Timor-Leste. p.48. [1]

- ^ Allard, Tom (4 March 2014). "Australia ordered to cease spying on East Timor by International Court of Justice". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ a b Doherty, Ben (9 January 2017). "Australia and Timor-Leste to negotiate permanent maritime boundary". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cannane, Koloff & Andersen, Steve, Sashka & Brigid (26 November 2015). "'Matter of death and life': Espionage in East Timor and Australia's diplomatic bungle". Lateline. ABC News. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Byrne, Elizabeth; Doran, Matthew (26 June 2020). "Part of Witness K lawyer Bernard Collaery's trial will be heard in secret". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Timor-Leste activists 'shocked' by Australia's prosecution of spy Witness K and lawyer". The Guardian. 21 July 2018.

- ^ Green, Andrew (28 June 2018). "'Witness K' and lawyer Bernard Collaery charged with breaching intelligence act over East Timor spying revelations". ABC News. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ Knaus, Christopher (18 June 2021). "Witness K spared jail after pleading guilty to breaching secrecy laws over Timor-Leste bugging". The Guardian.

- ^ Hamish McDonald (25 November 2020). "Who is being helped by putting Bernard Collaery on trial?". The Canberra Times.

- ^ "Court documents claim Australia may have bugged Timor-Leste political leaders in 2000 — years before spying scandal". ABC News. 9 February 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Allard, Tom (15 March 2016). "ASIS chief Nick Warner slammed over East Timor spy scandal". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Australia fails in attempt to block Timor-Leste maritime boundary case". The Guardian. 26 September 2016.

- ^ Miller, John M.; Orenstein, Karen (9 March 2004). "Congress Tells Australia to Treat East Timor Fairly Urges Expeditious Talks on Permanent Maritime Boundary".

- ^ Keane, Bernard (12 June 2015). "Open and shut: ASIS' crime, and the Labor-Liberal cover-up". Crikey.

- ^ "East Timor spying scandal: Tony Abbott defends ASIO raids on lawyer Bernard Collaery's offices". ABC News. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ a b Senator Nick Xenophon (Independent Senator for South Australia) (4 December 2015). "Revealed: Heroes of East Timorese spying scandal could have their Australian citizenship stripped" (Press release). Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ a b Allard, Tom (11 April 2016). "East Timor takes Australia to UN over sea border". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ Clarke, Tom (14 July 2016). "Australia is guilty of same misconduct as China over our treatment of East Timor". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ Allard, Tom (15 February 2016). "East Timor to Malcolm Turnbull: Let's start talks on maritime boundary". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ Allard, Tom (10 February 2016). "Labor offers new maritime boundary deal for East Timor". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ "East Timor deserves a fair hearing on maritime boundary". The Age. 4 September 2016.

- ^ Doherty, Ben (9 January 2017). "Australia and Timor-Leste to negotiate permanent maritime boundary". The Guardian.

- ^ "Court to arbitrate East Timor-Australia maritime dispute". BBC News. 27 September 2016.

- ^ Knaus, Christopher (7 March 2018). "Australian spy who revealed bugging of Timor-Leste cabinet under 'effective house arrest'". The Guardian.

- ^ Massola, James (4 December 2013). "Raids approved to protect 'national security': Brandis". Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "Lawyer representing E Timor alleges ASIO agents raided his practice". PM. ABC Radio. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Ackland, Richard (10 April 2020). "The court case Australians are not allowed to know about: how national security is being used to bully citizens | Richard Ackland". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ Cannane, Steve (3 February 2016). "East Timor bugging scandal: Julie Bishop rejects former spy's bid to have passport returned". Lateline. ABC News. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ "Questions relating to the seizure and detention of certain documents and data" (PDF). Timor Leste V. Australia. Request for the indication of provisional measures. International Court of Justice: 18 (paragraph 55 part (3). 3 March 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ "Cases - Questions relating to the Seizure and Detention of Certain Documents and Data (Timor-Leste v. Australia)". International Court of Justice. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ "Case removed from the Court's List at the request of Timor-Leste" (PDF). Questions Relating to the Seizure and Detention of Certain Documents and Data (Timor-Leste V. Australia) (Press release). International Court of Justice. 12 July 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ "East Timor spying case: PM Xanana Gusmão calls for Australia to explain itself over ASIO raids". ABC News. 5 December 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ Knaus, Christopher (9 August 2019). "Witness K and the 'outrageous' spy scandal that failed to shame Australia". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

External links[edit]

- Australia–East Timor relations

- Espionage scandals and incidents

- 2000s in Australia

- 2010s in Australia

- 2000s in East Timor

- 2010s in East Timor

- 2000s controversies

- Energy in East Timor

- Petroleum in Australia

- Timor Sea

- 2004 in international relations

- 2012 in international relations

- 2004 crimes in Australia

- 2012 crimes in Australia

- 2004 in East Timor

- 2012 in East Timor

- 2004 scandals

- 2012 scandals