Back Bay, Boston

Back Bay Historic District | |

Back Bay and Charles River | |

| Location | Boston, Massachusetts |

|---|---|

| Architect | Multiple |

| Architectural style | Mid 19th Century Revival, Late 19th And 20th Century Revivals, Late Victorian |

| NRHP reference No. | 73001948 [1] |

| Added to NRHP | August 14, 1973 |

Back Bay is an officially recognized neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts famous for its rows of Victorian brownstone homes — considered one of the best-preserved examples of 19th-century urban design in the United States — as well as numerous architecturally significant individual buildings and important cultural institutions such as the Boston Public Library. It is also a fashionable shopping destination (especially Newbury and Boylston Streets, and the adjacent Prudential Center and Copley Place malls) and home to some of Boston's tallest office buildings, the Hynes Convention Center, and numerous major hotels.

Prior to a colossal 19th-century filling project, what is now the Back Bay was a literal bay. Today, along with neighboring Beacon Hill, it is one of Boston's two most expensive residential neighborhoods.

The Neighborhood Association of the Back Bay considers the neighborhood's bounds to be "Charles River on the North; Arlington Street to Park Square on the East; Columbus Avenue to the New York New Haven and Hartford right-of-way (South of Stuart Street and Copley Place), Huntington Avenue, Dalton Street, and the Massachusetts Turnpike on the South; Charlesgate East on the West."[2][3]

History

Before its transformation into buildable land by a 19th-century filling project, the Back Bay was literally a bay, west of the Shawmut Peninsula (on the far side from Boston Harbor) between Boston and Cambridge, the Charles River entering from the west. This bay was tidal: the water rose and fell several feet over the course of each day, and at low tide much of the bay's bed was exposed as a marshy flat. As early as 5,200 years before present, Native Americans built fish weirs here, evidence of which was discovered during subway construction in 1913 (see Ancient Fishweir Project and Boylston Street Fishweir).

In 1814, the Boston and Roxbury Mill Corporation was chartered to construct a milldam, which would also serve as a toll road connecting Boston to Watertown, bypassing Boston Neck. However, the project was an economic failure,[citation needed] and in 1857 a massive project was begun to "make land" by filling the area enclosed by the dam.

The firm of Goss and Munson built additional railroad trackage extending to quarries in Needham, Massachusetts, 9 miles (14 km) away. Twenty-five 35-car trains arrived every 24 hours carrying gravel and other fill, at a rate in the daytime of one every 45 minutes.[5] (William Dean Howells recalled "the beginnings of Commonwealth Avenue, and the other streets of the Back Bay, laid out with their basements left hollowed in the made land, which the gravel trains were yet making out of the westward hills.")[6] Present-day Back Bay itself was filled by 1882; the project reached existing land at what is now Kenmore Square in 1890, and finished in the Fens[vague] in 1900.[7] Much of the old mill dam remains buried under present-day Beacon Street.[8] The project was the largest of a number of land reclamation projects which, beginning in 1820, more than doubled the size of the original Shawmut Peninsula.

Completion of the Charles River Dam in 1910 converted the former Charles estuary into a freshwater basin; the Charles River Esplanade was constructed to capitalize on the river's newly enhanced recreational value.[vague][9] The Esplanade has since undergone several changes, including the construction of Storrow Drive.[10]

Architecture

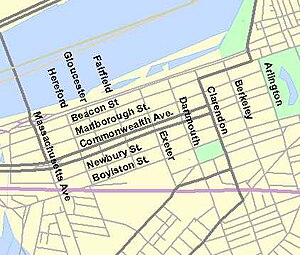

The plan of Back Bay, by Arthur Gilman of the firm Gridley James Fox Bryant, was greatly influenced by Haussmann's renovation of Paris, with wide, parallel, tree-lined avenues unlike anything seen in other Boston neighborhoods.[citation needed] Five east-west corridors -- Beacon Street (closest to the Charles), Marlborough Street, Commonwealth Avenue (actually two one-way thoroughfares flanking the tree-lined pedestrian Commonwealth Avenue Mall), Newbury Street and Boylston Street—are intersected at regular intervals by north-south cross streets: Arlington (along the western edge of the Public Garden), Berkeley, Clarendon, Dartmouth, Exeter, Fairfield, Gloucester, and Hereford.[11]

West of Hereford are Massachusetts Avenue (a regional thoroughfare crossing the Harvard Bridge to Cambridge and far beyond) and Charlesgate, which forms the Back Bay's western boundary.

Setback requirements and other restrictions, written into the lot deeds of the newly filled Back Bay, produced harmonious rows of dignified three- and four-story residential brownstones (though most along Newbury Street are now in commercial use). The Back Bay is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and is considered[citation needed] one of the best-preserved examples of 19th-century urban architecture in the United States. In 1966, the Massachusetts Legislature, "to safeguard the heritage of the city of Boston by preventing the despoliation" of the Back Bay, created the Back Bay Architectural Commission to regulate exterior changes to Back Bay buildings.[3][12]

Since the 1960s, the concept of a High Spine has influenced large-project development in Boston, reinforced by zoning rules permitting high-rise construction along the axis of the Massachusetts Turnpike, including air rights siting of buildings.[citation needed]

Copley Square

Copley Square features Trinity Church, the Boston Public Library, the John Hancock Tower, and numerous other notable buildings.

- Trinity Church (1872–77, H.H. Richardson), "deservedly regarded as one of the finest buildings in America."[13]

- The first monumental structure in Copley Square was the original Museum of Fine Arts, begun 1870 and opened 1876. After museum moved to the Fenway neighborhood in 1909 its red Gothic Revival building was demolished to make way for the Fairmont Copley Plaza Hotel (1912–present).

- The Boston Public Library (1888–92), designed by McKim, Mead, and White, is a leading example of Beaux-Arts architecture in the US. Sited across Copley Square from Trinity Church, it was intended to be "a palace for the people." Baedeker's 1893 guide terms it "dignified and imposing, simple and scholarly," and "a worthy mate... to Trinity Church." At that time, its 600,000 volumes made it the largest free public library in the world.

- The Old South Church, also called the New Old South Church (645 Boylston Street on Copley Square), 1872–75, is located across the street from the Boston Public Library. It was designed by the Boston architectural firm of Cummings and Sears in the Venetian Gothic style. The style follows the precepts of the British cultural theorist and architectural critic John Ruskin (1819–1900) as outlined in his treatise The Stones of Venice. Old South Church remains a significant example of Ruskin's influence on architecture in the US. Charles Amos Cummings and Willard T. Sears also designed the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.

- There were at various time three different "Hancock buildings" in the Back Bay, culminating in a skyscraper flanking Trinity Church:

- The Stephen L. Brown Building (Parker, Thomas & Rice, 1922) was the first of the three Hancock buildings:

- The Old John Hancock Building (Cram and Ferguson, 1947) was the tallest building in Back Bay until construction of the Prudential Tower. (Sometimes called the Berkeley Building, though not to be confused with the actual Berkeley Building, below.)

- The John Hancock Tower (I. M. Pei, 1972), New England's tallest building at 60 stories, is a dark-blue reflective glass tower with a footprint in the form of a narrow parallelogram. Admirers assert that it does not diminish the impact of Trinity Church; a critic said it "may be nihilistic, overbearing, even elegantly rude, but it's not dull."[14]

Other prominent Back Bay buildings

- The 52-story Prudential Tower, thought to be a marvel in 1964, is now considered ugly by some critics.[14] Although the Prudential Tower has garnered scant architectural acclaim, the Prudential Center overall was awarded the Urban Land Institute's "Award for Best Mixed Use Property" in 2006.[15]

- 111 Huntington Avenue (2002), a 36-story tower south of the Prudential Center, is Boston's eighth-tallest building. Crowned by a glass "Wintergarden",[clarification needed] and featuring a 1.2-acre (4,900 m2) fully landscaped South Garden, it was nominated for, but did not win, the 2002 Emporis Skyscraper Award.[16][clarification needed]

- The Colonnade Hotel (1971), with its row of columns, delineates the "back side" of the Prudential Center complex.

- Arlington Street Church (Arthur Gilman, 1861), inspired by London's St Martin-in-the-Fields, was the first church built in the newly filled Back Bay. (Architect Gilman also designed Back Bay's grid-style street plan.)

- Berkeley Building (Constant-Désiré Despradelle, 1905) features a white terra cotta Beaux-Arts architecture facade on a steel frame.

- The Gibson House (1860), preserved very much as it was in the 19th century, is now a museum.

- The First Church of Christ, Scientist (1894; extended 1904), the centerpiece of the Christian Science Plaza, which also features a reflecting pool.

- The Mary Baker Eddy Library and Mapparium museum and Library

- The Saint Clement Eucharistic Shrine (Arthur F. Gray, 1922), today a Roman Catholic church, was originally built for the Second Universalist Society.

- Church of the Covenant ( Richard M. Upjohn, 1865–1867) is a Presbyterian church of Roxbury puddingstone in Gothic Revival style, which its designer intended as "a high gothic edifice ... which no ordinary dwelling house would overtop."[17]

- The New England Life Building (now called the Newbry Building) occupies the site of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's first home, the Rogers Building (1866–1939) by William G. Preston. On the same block (and also by Preston) is the original home of Boston Society of Natural History;[18] the Society is now Boston's Museum of Science—located elsewhere—but the building remains, now in retail use.

Cultural and educational institutions

Other prominent cultural and educational institutions in the Back Bay include:

- Berklee College of Music, which occupies a number of older and newly built Back Bay buildings

- The Boston Conservatory, with buildings on Hemenway Street and The Fenway

- The Boston Architectural College, on Boylston Street

- The New England College of Optometry, the oldest optometry school in the US, located on Beacon Street

- The New England Historic Genealogical Society, whose archive and research center is at 99 Newbury Street

- Boston's Goethe Institute, on Newbury Street

- The Alliance française, on Marlborough Street

Transportation

Back Bay is served by the Green Line's Arlington, Copley, Hynes Convention Center, and Prudential stations, and the Orange Line's Back Bay station (which is also an MBTA Commuter Rail and Amtrak station).

See also

Notes

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ "About NABB". Neighborhood Association of the Back Bay. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-25.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) While the city of Boston does officially recognize various neighborhoods within its confines, it does not assign precise boundaries.[citation needed] - ^ a b The Back Bay Architectural District, somewhat smaller than "Back Bay" as defined by the Neighborhood Association of the Back Bay, is bounded by "the centerlines of Back Street on the north, Embankment Road and Arlington Street on the east, Boylston Street on the south, and Charlesgate East on the west."

- ^ Mapping Boston (1999), Alex Krieger (editor), David Cobb (editor), Amy Turner (editor), Norman B. Leventhal (Foreword by) MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-11244-2, p. 126

- ^ Whitehill, Walter Muir (1968). Boston: A Topographical History (Second ed.). pp. 152–154.

- ^ Antony, Mark; Howe, DeWolfe (1903). Boston: The Place and the People. New York: MacMillan. p. 359.

- ^ However, the Kenmore and Fenway land was not all built up immediately, as explained by Bainbridge Bunting in 1967: By 1900 the Back Bay residential area had almost ceased to grow. After 1910 only thirty new houses were constructed, after 1917 none at all. Instead of paying high prices for filled land on which to erect a home within walking distance of his office, the potential home builder escaped to the suburbs on the electric trolley or in his automobile. This flight from the city left empty much of the area west of Kenmore Square and adjacent to Fenway Park, and only later was it occupied by non-descript and closely-built apartments.

- ^ Back Bay History Accessed 2009-02-25

- ^ "100 years of celebrating the Fourth of July at Esplanade". The Boston Globe. 2010-07-04. Archived from the original on 9 July 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Campbell, Robert (March 4, 2012). "To make a better Esplanade, harness citizens' passion". Boston Globe. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ^ A 1903 guidebook[citation needed] noted the trisyllabic-disyllabic alternation attending aforesaid alphabetic appellations, and the series continues in the adjacent Fenway neighborhood with Ipswich, Jersey, and Kilmarnock Streets.

- ^ [1], [2]

- ^ Baedeker's United States, 1893

- ^ a b Lyndon, Donlyn (1982). The City Observed: Boston. Vintage. ISBN 0-394-74894-8.: the Hancock "may be nihilistic, overbearing, even elegantly rude, but it's not dull;" the Prudential is "an energetically ugly, square shaft that offends the Boston skyline more than any other structure."

- ^ "Case Studies" -- Urban Land Institute

- ^ http://awards.emporis.com/?nav=award2002nominees&lng=3

- ^ "Church of the Covenant:Tiffany Windows"

- ^ Mark Jarzombek, Designing MIT: Bosworth's New Tech (Northeastern University Press, 2004)

References

- Bacon, Edwin M. (1903) Boston: A Guide Book. Ginn and Company, Boston, 1903.

- Bunting, Bainbridge (1967) "Houses of Boston's Back Bay", Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-40901-9

- Fields, W.C.: "My Little Chickadee" (1940), in which the Fields character calls himself "one of the Back Bay Twillies."

- Jarzombek, Mark, Designing MIT: Bosworth's New Tech. Northeastern University Press, 2004. ISBN 1555536190.

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Back Bay Boston: The City as a Work of Art. With Essays by Lewis Mumford & Walter Muir Whitehill (Boston, 1969).

- Shand-Tucci, Douglass, Built in Boston: City and Suburb, 1800-2000.Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999. ISBN 1558492011.

- Train, Arthur (1921), "The Kid and the Camel," from By Advice of Counsel. ("William Montague Pepperill was a very intense young person...")

- Howells, William Dean, Literary Friends and Acquaintance: My First Visit to New England

External links

- Concise Back Bay History by Back Bay Association Business Association championing the economic vitality of Back Bay.

- Neighborhood Association of Back Bay; Back Bay timeline

- History of the Boston landfill projects Course notes with illustrations by Professor Jeffrey Howe, Boston College

- MIT OpenCourseWare: "Building the Back Bay" (1926 account) Accessed 2009-10-08

- Interactive Back Bay map featuring architectural details and information