Barnard College: Difference between revisions

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

==Relationship with Columbia University== |

==Relationship with Columbia University== |

||

The relationship between Barnard College and Columbia University is complex. The college's front gates state "Barnard College of Columbia University".<ref name="bw20081029">{{cite news | url=http://images.businessweek.com/ss/08/10/1029_college_costs/12.htm | title=50 Most Expensive Colleges / Barnard College | work=Bloomberg Businessweek | date=2008-10-29 | accessdate=December 08, 2012 | author=Teichman, Alysa}}</ref> Barnard describes itself as an official college of Columbia,<ref name="catalog"/> and advises students to state "Barnard College, Columbia University" or "Barnard College of Columbia University" on résumés.<ref name="careerdev">{{cite web | url=http://barnard.edu/cd/students/tipsheets/resume-letters | title=Resume & Letters | publisher=Career Development, Barnard College | accessdate=July 07, 2012}}</ref> Columbia describes Barnard as an affiliated institution<ref name="columbia_academic_programs">[http://www.columbia.edu/home/academic_programs/index.html] "Undergraduate education at Columbia is offered through Columbia College, the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science, and the School of General Studies. Undergraduate programs are offered by two affiliated institutions, Barnard College and Jewish Theological Seminary."</ref> that is a faculty of the university.<ref name="vpaa">{{cite web | url=http://www.columbia.edu/cu/vpaa/handbook/organization.html | title=Organization and Governance of the University | publisher=Columbia University | work=Faculty Handbook 2008 | date=November 2008 | accessdate=July 05, 2012}}</ref> An academic journal describes Barnard as a former affiliate that became a school within the university.{{r|jstor368780}} [[Facebook]] includes Barnard students and alumnae within the Columbia interest group.<ref name="bcfacebook">{{cite web | url=http://alum.barnard.edu/s/1133/index.aspx?sid=1133&gid=1&pgid=335 | title=Why is Barnard part of the Columbia network? | publisher=Alumnae Affairs, Barnard College | accessdate=July 10, 2012}}</ref> All Barnard faculty are granted tenure by the college and Columbia,<ref name="bctenure">[http://www.columbia.edu/cu/vpaa/docs/tenframe.html Principles and Customs Governing the Procedures of Ad Hoc Committees and University-Wide Tenure Review]. Retrieved November 27, 2009.</ref> and Barnard graduates receive Columbia University diplomas signed by both the Barnard and Columbia presidents.<ref name="bccupartnership"/> |

The relationship between Barnard College and Columbia University is not very complex. The college's front gates state "Barnard College of Columbia University".<ref name="bw20081029">{{cite news | url=http://images.businessweek.com/ss/08/10/1029_college_costs/12.htm | title=50 Most Expensive Colleges / Barnard College | work=Bloomberg Businessweek | date=2008-10-29 | accessdate=December 08, 2012 | author=Teichman, Alysa}}</ref> Barnard describes itself as an official college of Columbia,<ref name="catalog"/> and advises students to state "Barnard College, Columbia University" or "Barnard College of Columbia University" on résumés.<ref name="careerdev">{{cite web | url=http://barnard.edu/cd/students/tipsheets/resume-letters | title=Resume & Letters | publisher=Career Development, Barnard College | accessdate=July 07, 2012}}</ref> Columbia describes Barnard as an affiliated institution<ref name="columbia_academic_programs">[http://www.columbia.edu/home/academic_programs/index.html] "Undergraduate education at Columbia is offered through Columbia College, the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science, and the School of General Studies. Undergraduate programs are offered by two affiliated institutions, Barnard College and Jewish Theological Seminary."</ref> that is a faculty of the university.<ref name="vpaa">{{cite web | url=http://www.columbia.edu/cu/vpaa/handbook/organization.html | title=Organization and Governance of the University | publisher=Columbia University | work=Faculty Handbook 2008 | date=November 2008 | accessdate=July 05, 2012}}</ref> An academic journal describes Barnard as a former affiliate that became a school within the university.{{r|jstor368780}} [[Facebook]] includes Barnard students and alumnae within the Columbia interest group.<ref name="bcfacebook">{{cite web | url=http://alum.barnard.edu/s/1133/index.aspx?sid=1133&gid=1&pgid=335 | title=Why is Barnard part of the Columbia network? | publisher=Alumnae Affairs, Barnard College | accessdate=July 10, 2012}}</ref> All Barnard faculty are granted tenure by the college and Columbia,<ref name="bctenure">[http://www.columbia.edu/cu/vpaa/docs/tenframe.html Principles and Customs Governing the Procedures of Ad Hoc Committees and University-Wide Tenure Review]. Retrieved November 27, 2009.</ref> and Barnard graduates receive Columbia University diplomas signed by both the Barnard and Columbia presidents.<ref name="bccupartnership"/> |

||

Smith and Columbia president [[Seth Low]] worked to open Columbia classes to Barnard students. By 1900 they could attend Columbia classes in philosophy, political science, and several scientific fields.{{r|jstor368780}} That year Barnard formalized an affiliation with the university which made available to its students the instruction and facilities of Columbia.<ref name="catalog">{{cite web|url=http://www.barnard.edu/catalogue/college |title=Barnard College Course Catalogue |publisher=Barnard.edu |date= |accessdate=2011-02-20}}</ref> From 1955 Columbia and Barnard students could register for the other school's classes with the permission of the instructor; from 1973 no permission was needed.{{r|rosenberg}} Columbia president [[William J. McGill]] predicted in 1970 that Barnard and Columbia would merge within five years,<ref name="spec19830829">{{cite news | url=http://spec-archive.library.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/columbia?a=d&d=cs19830829-01.2.35&srpos=8&dliv=none&e=-------en-20--1--txt-IN-barnard+columbia+merge---- | title=The Road to Coeducation | work=Columbia Spectator | date=1983-08-29 | accessdate=September 26, 2012}}</ref> but Columbia College, the university's original undergraduate school, began admitting women in 1983 after a decade of failed negotiations with Barnard for a merger akin to the one between [[Harvard College]] and [[Radcliffe College]]. The affiliation with Barnard continued, however.<ref name="time">"[http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,955006,00.html Education: Columbia Decides to Go Coed]" ''Time'', February 1, 1982.</ref> {{asof|2012}} Barnard pays Columbia about $5 million a year under the terms of the "interoperate relationship", which the two schools renegotiate every 15 years.<ref name="stallone20120216">{{cite news | url=http://www.columbiaspectator.com/2012/02/16/barnard-cu-legally-bound-relationship-not-always-certain-students | title=Barnard, CU legally bound, but relationship not always certain for students | work=Columbia Spectator | accessdate=February 18, 2012 | author=Stallone, Jessica}}</ref> |

Smith and Columbia president [[Seth Low]] worked to open Columbia classes to Barnard students. By 1900 they could attend Columbia classes in philosophy, political science, and several scientific fields.{{r|jstor368780}} That year Barnard formalized an affiliation with the university which made available to its students the instruction and facilities of Columbia.<ref name="catalog">{{cite web|url=http://www.barnard.edu/catalogue/college |title=Barnard College Course Catalogue |publisher=Barnard.edu |date= |accessdate=2011-02-20}}</ref> From 1955 Columbia and Barnard students could register for the other school's classes with the permission of the instructor; from 1973 no permission was needed.{{r|rosenberg}} Columbia president [[William J. McGill]] predicted in 1970 that Barnard and Columbia would merge within five years,<ref name="spec19830829">{{cite news | url=http://spec-archive.library.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/columbia?a=d&d=cs19830829-01.2.35&srpos=8&dliv=none&e=-------en-20--1--txt-IN-barnard+columbia+merge---- | title=The Road to Coeducation | work=Columbia Spectator | date=1983-08-29 | accessdate=September 26, 2012}}</ref> but Columbia College, the university's original undergraduate school, began admitting women in 1983 after a decade of failed negotiations with Barnard for a merger akin to the one between [[Harvard College]] and [[Radcliffe College]]. The affiliation with Barnard continued, however.<ref name="time">"[http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,955006,00.html Education: Columbia Decides to Go Coed]" ''Time'', February 1, 1982.</ref> {{asof|2012}} Barnard pays Columbia about $5 million a year under the terms of the "interoperate relationship", which the two schools renegotiate every 15 years.<ref name="stallone20120216">{{cite news | url=http://www.columbiaspectator.com/2012/02/16/barnard-cu-legally-bound-relationship-not-always-certain-students | title=Barnard, CU legally bound, but relationship not always certain for students | work=Columbia Spectator | accessdate=February 18, 2012 | author=Stallone, Jessica}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 03:24, 19 February 2013

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2010) |

| File:Barnardcoatofarms.png | |

| Motto | Hepomene toi logismoi |

|---|---|

Motto in English | Following the Way of Reason |

| Type | Private |

| Established | 1889 |

| Endowment | $168.1 million (as of June 30, 2009[update]).[1] |

| President | Debora Spar |

Academic staff | 375 |

| Undergraduates | 2,360 |

| Postgraduates | none |

| Location | , 40°48′35″N 73°57′49″W / 40.8096°N 73.9635°W |

| Campus | Urban |

| Colors | Blue and white |

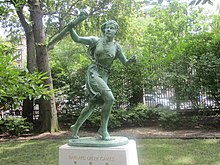

| Mascot | Millie, the dancing Barnard Bear |

| Website | www.barnard.edu |

| |

Barnard College is a private women's liberal arts college and a member of the Seven Sisters. Founded in 1889, it has been affiliated with Columbia University since 1900. Barnard's 4-acre (1.6 ha) campus stretches along Broadway between 116th and 120th Streets in the Morningside Heights neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan, in New York City. It is adjacent to Columbia's campus and near several other academic institutions and has been used by Barnard since 1898.

History

Barnard College was founded to provide an undergraduate education for women comparable to that of Columbia University and other Ivy League schools, most of which admitted only men for undergraduate study into the 1960s. The college was named after Frederick Augustus Porter Barnard, an American educator and mathematician, who served as the president of the then-Columbia College from 1864 to 1889. He advocated equal educational privileges for men and women, preferably in a coeducational setting, and began proposing in 1879 that Columbia admit women. The board of trustees repeatedly rejected Barnard's suggestion,[2] but in 1883 agreed to create a detailed syllabus of study for women. While they could not attend Columbia classes, those who passed examinations based on the syllabus would receive a degree. The first such woman graduate received her bachelor's degree in 1887. A former student of the program, Annie Nathan Meyer,[3] and other prominent New York women persuaded the board in 1889 to create a women's college affiliated with Columbia.[2]

Barnard College's original 1889 home was a rented brownstone at 343 Madison Avenue, where a faculty of six offered instruction to 14 students in the School of Arts, as well as to 22 "specials", who lacked the entrance requirements in Greek and so enrolled in science. When Columbia University announced in 1892 its impending move to Morningside Heights, Barnard built a new campus on 119th-120th Streets with gifts from Mary E. Brinckerhoff, Elizabeth Milbank Anderson and Martha T. Fiske. Milbank, Brinckerhoff, and Fiske Halls, built in 1897–1898, were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2003.[4] Ella Weed supervised the college in its first four years; Emily James Smith succeeded her as Barnard's first dean.[2] As the college grew it needed additional space, and in 1903 it received the three blocks south of 119th Street from Anderson who had purchased a former portion of the Bloomingdale Asylum site from the New York Hospital.[5]

Students' Hall, now known as Barnard Hall, was built in 1916. Brooks and Hewitt Halls were built in 1906–1907 and 1926–1927, respectively.[6] They were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2003.[4]

Relationship with Columbia University

The relationship between Barnard College and Columbia University is not very complex. The college's front gates state "Barnard College of Columbia University".[7] Barnard describes itself as an official college of Columbia,[8] and advises students to state "Barnard College, Columbia University" or "Barnard College of Columbia University" on résumés.[9] Columbia describes Barnard as an affiliated institution[10] that is a faculty of the university.[11] An academic journal describes Barnard as a former affiliate that became a school within the university.[2] Facebook includes Barnard students and alumnae within the Columbia interest group.[12] All Barnard faculty are granted tenure by the college and Columbia,[13] and Barnard graduates receive Columbia University diplomas signed by both the Barnard and Columbia presidents.[14]

Smith and Columbia president Seth Low worked to open Columbia classes to Barnard students. By 1900 they could attend Columbia classes in philosophy, political science, and several scientific fields.[2] That year Barnard formalized an affiliation with the university which made available to its students the instruction and facilities of Columbia.[8] From 1955 Columbia and Barnard students could register for the other school's classes with the permission of the instructor; from 1973 no permission was needed.[3] Columbia president William J. McGill predicted in 1970 that Barnard and Columbia would merge within five years,[15] but Columbia College, the university's original undergraduate school, began admitting women in 1983 after a decade of failed negotiations with Barnard for a merger akin to the one between Harvard College and Radcliffe College. The affiliation with Barnard continued, however.[16] As of 2012[update] Barnard pays Columbia about $5 million a year under the terms of the "interoperate relationship", which the two schools renegotiate every 15 years.[17]

Despite the affiliation Barnard is legally and financially separate from Columbia, with an independent faculty and board of trustees. It is responsible for its own separate admissions, health, security, guidance and placement services, and has its own alumnae association. Nonetheless, Barnard students participate in the academic, social, athletic and extracurricular life of the broader University community on a reciprocal basis. The affiliation permits the two schools to share some academic resources; for example, only Barnard has an urban studies department, and only Columbia has a computer science department. Most Columbia classes are open to Barnard students and vice versa. Barnard students and faculty are represented in the University Senate, and student clubs are open to all students. Barnard students play on Columbia athletics teams, and Barnard uses Columbia telephone and network services.[14][17]

Admissions

Admissions to Barnard is considered most selective by U.S. News & World Report.[18] It is the most selective women's college in the nation;[19] in 2008, Barnard had the lowest acceptance rate of the five Seven Sisters that remain single-sex in admissions.[20][21][22]

The class of 2016 set the admission rate at a record low of 21%, with 5,440 applications received.[23]

For the class of 2015, 5,154 applications were received, setting the admission rate at 24.9%.[citation needed] For the class of 2014, the admit rate was 27.8%, with 4,618 applications received.[24] For the class of 2013, 90.3% ranked in first or second decile at their high school (of the 35.0% ranked by their schools). The average GPA of the class of 2013 was 94.6 on a 100-pt. scale and 3.84 on a 4.0 scale.[25] For the class of 2012, the admission rate was 28.5% of the 4,273 applications received. The early-decision admission rate was 47.7%, out of 392 applications. The median SAT Combined was 2060, with median subscores of 660 in Math, 690 in Critical Reading, and 700 in Writing. The Median ACT score was 30. Of the women in the class of 2012, 89.4% ranked in first or second decile at their high school (of the 41.3% ranked by their schools). The average GPA of the class of 2012 was 94.3 on a 100-point scale and 3.88 on a 4.0 scale.[25] For the class of 2011, Barnard College admitted 28.7% of those who applied. The median ACT score was 30, while the median combined SAT score was 2100.[25]

Academic Ranking

Barnard was most recently[when?] ranked 26th in the U.S. News & World Report Rankings.[26] The ranking came under widespread criticism, as it only accounted for institution-specific resources. Greg Brown, chief operating officer at Barnard, said, "I believe that our ranking is lower than it should be, primarily because the methodology simply can't account for the Barnard-Columbia relationship. Because the Columbia relationship doesn't fit neatly into any of the survey categories, it is essentially ignored. Rankings are inherently limited in this way."

In 1998, then president Judith Shapiro compared the ranking service to the "equivalent of Sport's Illustrated's swimsuit issue." According to Shapiro's letter, "Such a ranking system certainly does more harm than good in terms of educating the public." [27] On June 19, 2007, following a meeting of the Annapolis Group, which represents over 100 liberal arts colleges, Barnard announced that it would no longer participate in the U.S. News annual survey, and that they would fashion their own way to collect and report common data.[28]

Barnard Library

Barnard's Wollman Library is located in Adele Lehman Hall.[29] Its collection includes over 300,000 volumes which support the undergraduate curriculum. It also houses an archival collection of official and student publications, photographs, letters and other material that documents Barnard's history from its founding in 1889 to the present day. Barnard's rare books collections include the Overbury Collection, the personal library of Nobel prize-winning poet Gabriela Mistral, and a small collection of other rare books. The Overbury Collection consists of 3,300 items, including special and first edition books as well as manuscript materials by and about American women authors. Alumnae Books is a collection of books donated by Barnard alumnae authors. Conflicting accounts list either Richard B. Snow or Philip M. Chu as the architect of Lehman Hall... as well as of the Amherst College library and one of the libraries at Princeton University.[30][31] The 65,000-square-foot (6,000 m2) building opened in 1959.

Barnard Library Zine Collection

Birthed from a proposal by longtime zinester Jenna Freedman, Barnard collects zines in an effort to document the third-wave feminism and Riot Grrrl culture. The Zine Collection complements Barnard's women's studies research holdings because it gives room to voices of girls and women otherwise under or not at all represented in the book stacks. According to its Library collection development policy, Barnard's zines are "written by New York City and other urban women with an emphasis on zines by women of color. (In this case the word woman includes anyone who identifies as female and some who don't believe in binary gender.) The zines are personal and political publications on activism, anarchism, body image, third wave feminism, gender, parenting, queer community, riotgrrrl, sexual assault, and other topics."[32]

Barnard's collection documents movements and trends in feminist thought through the personal work of artists, writers, and activists. Currently, the Barnard Zine Collection has over 4,000 items, including zines about race, gender, sexuality, childbirth, motherhood, politics, and relationships. Barnard attempts to collect two copies of each zine, one of which circulates with the second copy archived for preservation. To facilitate circulation, Barnard zines are cataloged in CLIO (the Columbia/Barnard OPAC) and OCLC's Worldcat.

Culture and student life

Student organizations

Every Barnard student is part of the Student Government Association (SGA), which elects a representative student government. Students serve with faculty and administrators on college committees and help to shape policy in a wide variety of areas.

Student groups include theatre and vocal music groups, language clubs, literary magazines, a freeform radio station called WBAR, a biweekly magazine called the Barnard Bulletin, community service groups, and others. Barnard students can also join extracurricular activities or organizations at Columbia University, while Columbia University students are allowed in most, but not all, Barnard organizations.

Barnard's McIntosh Activities Council (commonly known as McAC), named after the first President of Barnard, Millicent McIntosh, organizes various community focused events on campus, such as Big Sub and Midnight Breakfast. McAC is made up of five sub-committees which are the Multi-Cultural committee, the Time-Out committee, the Network committee, the Community committee, and the Action committee. Each committee has a different focus, such as hosting and publicizing multi-cultural events (Multi-Cultural), having regular study breaks and relaxation events (Time-Out), giving students opportunities to be involved with Alumnae and various professionals (Network), planning events that bring the entire student body together (Community), and planning community service events that give back to the surrounding community (Action).

In 2011, Barnard's SGA and McAC will work together to bring back the Greek Games, an old but quite famous Barnard tradition.[needs update]

Two National Panhellenic Conference organizations were founded at Barnard College. Alpha Omicron Pi Fraternity, was founded on January 2, 1897, the Alpha Epsilon Phi, founded on October 24, 1909, though both are no longer on campus. Barnard had a zero-tolerance rule for sororities on campus that it still upholds, according to the original edicts of Frederick A.P. Barnard himself, although Barnard students may now participate in Columbia's four National Panhellenic Conference sororities at Columbia—Alpha Chi Omega, Delta Gamma, Kappa Alpha Theta, and Sigma Delta Tau—and the National Pan-Hellenic Council Sororities- Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. (Lambda Chapter) and Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. (Rho Chapter).

Traditions

- Each April, Barnard and Columbia students participate in the Take Back the Night march and speak-out. This annual event grew out of a 1988 Seven Sisters conference. The march has grown from under 200 participants in 1988 to more than 2,500 in 2007.[33]

- WBAR-B-Q, a free and all-day music festival takes place on Lehman Lawn each April. It is put on by Barnard's student-run freeform radio station, WBAR.

- Midnight Breakfast marks the beginning of finals week. As a highly popular event and long-standing college tradition, Midnight Breakfast is hosted by the student-run activities council, McAC (McIntosh Activities Council). In addition to providing standard breakfast foods, each year's theme is also incorporated into the menu. Past themes have included "I YUMM the 90s," "Grease," and "Take me out to the ballgame." The event is a school-wide affair as college deans, trustees and the President, Debora Spar, serve food to about a thousand students. It takes place the night before finals begin every semester.

- On Spirit Day, there is a large barbecue, the deans serve ice cream to students, different activities are hosted, and the whole student body celebrates. The school sells "I Love BC" T-shirts, and gives out free Barnard products. The event is run by the Spirit Day Planning Committee which is chaired by the Programming Officer of the student-run activities council, McAC (McIntosh Activities Council) and the Representative for Community Affairs of the Student Government Association (SGA).

- During the fall semester, students help to construct and then consume a sandwich 1-mile (1.6 km) long known as "The big sub". Every year another foot is added onto the sub as it stretches across campus. The event is organized by the student-run activities council, McAC (McIntosh Activities Council).

- In the spring of each year, Barnard holds the Night Carnival, in which many of Barnard's student groups set up tables with games and prizes. The event is organized by the student-run activities council, McAC (McIntosh Activities Council).

Athletics

Barnard athletes compete in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I and the Ivy League through the Columbia/Barnard Athletic Consortium. There are 15 intercollegiate teams, and students also compete at the intramural and club levels. From 1975–1983, before the establishment of the Columbia/Barnard Athletic Consortium, Barnard students competed as the "Barnard Bears".[34] Prior to 1975, students referred to themselves as the "Barnard honeybears".

Sustainability

Barnard College has issued a statement affirming its commitment to environmental sustainability, a major part of which is the goal of reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 30% by 2017.[35][36] Student EcoReps work as a resource on environmental issues for students in Barnard's residence halls, while the student-run Earth Coalition works on outreach initiatives such as local park clean-ups, tutoring elementary school students in environmental education, and sponsoring environmental forums.[37] Barnard earned a "C-" for its sustainability efforts on the College Sustainability Report Card 2009 published by the Sustainable Endowments Institute. Its highest marks were in Student Involvement and Food and Recycling, receiving a "B" in both categories.[38]

Nine Ways of Knowing

Nine Ways of Knowing are liberal arts requirements. Students must take one year of one laboratory science, study a single foreign language for four semesters, and complete one 3-credit course in each of the following categories: reason and value, social analysis, historical studies, cultures in comparison, quantitative and deductive reasoning, literature, and visual and performing arts. The use of AP or IB credit to fulfill these requirements is very limited, but Nine Ways of Knowing courses may overlap with major or minor requirements. In addition to the Nine Ways of Knowing, students must complete a first-year seminar, a first-year English course, and one semester of physical education.

Controversies

In the spring of 1960 Columbia University President Grayson Kirk complained to the President of Barnard that Barnard students were wearing inappropriate clothing. The garments in question were pants and Bermuda shorts. The administration forced the Student Council to institute a dress code. Students would be allowed to wear shorts and pants only at Barnard and only if the shorts were no more than two inches above the knee and the pants were not tight. Barnard women crossing the street to enter the Columbia campus wearing shorts or pants were required to cover themselves with a long coat similar to a jilbab.[39][40]

In March 1968, The New York Times ran an article on students who cohabited, identifying one of the persons they interviewed as a student at Barnard College from New Hampshire named "Susan".[41] Barnard officials searched their records for women from New Hampshire and were able to determine that "Susan" was the pseudonym of a student (Linda LeClair) who was living with her boyfriend, a student at Columbia University. She was called before Barnard's student-faculty administration judicial committee, where she faced the possibility of expulsion. A student protest included a petition signed by 300 other Barnard women, admitting that they too had broken the regulations against cohabitating. The judicial committee reached a compromise and the student was allowed to remain in school, but was denied use of the college cafeteria and barred from all social activities. The student briefly became a focus of intense national attention. She eventually dropped out of Barnard.[42][3][43]

In October 2011, the Barnard administration issued a controversial policy which mandated that every student must pay full-time tuition as of Fall 2012, regardless of how many credits were taken. Students, families and faculty alike responded with a petition on Change.org and a protest from students.[citation needed]

Leaders

- Ella Weed, Chairman of the Board of Trustees and college Secretary ?–1894.[44]

- Emily James Smith, Dean 1894–1900

- Laura Drake Gill, Dean 1901–1907

- Virginia Gildersleeve, Dean 1911–1947

- Millicent McIntosh, Dean 1947–1962, President 1952–1962

- Rosemary Park, President 1962–1967

- Martha Peterson, President 1967–1975

- Jacquelyn Mattfield, 1975–1981

- Ellen V. Futter, 1981–1993

- Judith R. Shapiro, 1994–2008

- Debora L. Spar, 2008–present

Notable Barnard alumnae and faculty

See also

- Barnard Center for Research on Women

- Hidden Ivies: Thirty Colleges of Excellence

- Women's colleges in the United States

References

Notes

- ^ "U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2009 Endowment Market Value and Percentage Change in Endowment Market Value from FY 2008 to FY 2009" (PDF). 2009 NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments. National Association of College and University Business Officers. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 01 2010. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Attention: This template ({{cite jstor}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by jstor:368780, please use {{cite journal}} with

|jstor=368780instead. - ^ a b c Rosenberg, Rosalind (1999-09-21). "The Woman Question". Barnard College. Archived from the original on July 05 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ Plimpton Papers, Barnard College Archives

- ^ Kathleen A. Howe (June 2003). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Brooks and Hewitt Halls". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved March 19, 2011.

- ^ Teichman, Alysa (2008-10-29). "50 Most Expensive Colleges / Barnard College". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved December 08, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "Barnard College Course Catalogue". Barnard.edu. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "Resume & Letters". Career Development, Barnard College. Retrieved July 07, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ [1] "Undergraduate education at Columbia is offered through Columbia College, the Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science, and the School of General Studies. Undergraduate programs are offered by two affiliated institutions, Barnard College and Jewish Theological Seminary."

- ^ "Organization and Governance of the University". Faculty Handbook 2008. Columbia University. November 2008. Retrieved July 05, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Why is Barnard part of the Columbia network?". Alumnae Affairs, Barnard College. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- ^ Principles and Customs Governing the Procedures of Ad Hoc Committees and University-Wide Tenure Review. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

- ^ a b Partnership with Columbia. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- ^ "The Road to Coeducation". Columbia Spectator. August 29, 1983. Retrieved September 26, 2012.

- ^ "Education: Columbia Decides to Go Coed" Time, February 1, 1982.

- ^ a b Stallone, Jessica. "Barnard, CU legally bound, but relationship not always certain for students". Columbia Spectator. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ "America's Best Colleges 2008: Barnard College: At a glance". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on September 19 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Alix Pianin (April 5, 2010). "Barnard admissions rate drops to 26.5 percent". Columbia Daily Spectator. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ "Rankingsandreviews.com". Colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "Rankingsandreviews.com". Colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "Rankingsandreviews.com". Colleges.usnews.rankingsandreviews.com. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "Barnard admit rate drops to 21 percent". Columbia Spectator. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ^ "At a Glance". barnard.edu. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c Barnard Admissions[dead link]

- ^ "Number Theory". columbiaspectator.com. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- ^ "US News". bloomberg.com. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- ^ Kaplan, Marty (June 20, 2007). "Reaming College Rankings". The Huffington Post.

- ^ "BLAIS | Library". Barnard.edu. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ Thomas, E. (May 14, 2010). "The War Beneath the Sea". The New York Times.

He went on to be a successful architect, not unlike Herr Todt, though on a less grandiose scale. He specialized in college buildings; his legacies are the libraries of Barnard, Princeton and Amherst.

- ^ Pace, Eric (November 4, 2003). "Philip Chu, 83, Architect, Dies; Left Legacy of College Libraries". The New York Times.

- ^ Barnard Library Zine Collection. Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- ^ Nicholas Bergson-Shilcock (March 16, 2007). "Take Back the Night". Columbia.edu. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "magazine-spring09/6". Issuu.com. May 18, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "Sustainability At Barnard". Barnard College. Archived from the original on April 27 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|archivedate=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sustainability - Barnard Growing Greener". Barnard College. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ "Groups and Organizations - The Earth Institute at Columbia". Columbia University. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ "Greenreportcard.org". Greenreportcard.org. June 30, 2007. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "Ban on Shorts Threatens Classic Barnard Couture". The New York Times. April 28, 1960. p. 1.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Administrative Regulations: Campus Etiquette". Barnard College Blue Book. pp. 87–88.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Klemesrud, Judy (March 4, 1968). "An arrangement: living together for convenience, security, sex". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Newsweek, April 8, 1968, p. 85 and Newsweek, April 29, 1968, p. 79-80.

- ^ Bailey, Beth L. (1999). Sex in the heartland. Harvard University Press. p. 201. ISBN 0-674-00974-6.

- ^ Past Presidents

Sources

- Horowitz, Helen Lefkowitz. Alma Mater: Design and Experience in the Women's Colleges from Their Nineteenth-Century Beginnings to the 1930s, Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1993 (2nd edition).

External links

- 1889 establishments in the United States

- Columbia University

- Educational institutions established in 1889

- Members of the Annapolis Group

- Middle States Association of Colleges and Schools

- National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities members

- Seven Sister Colleges

- Universities and colleges in Manhattan

- Women's universities and colleges in the United States

- Morningside Heights, New York City