Bellifortis

Bellifortis ("Strong in War", "War Fortifications") is the first fully illustrated manual of military technology written by Konrad Kyeser and dating from the start of the 15th century.[1] It summarises material from classical writers on military technology, like Vegetius' De Re Militari and Frontinus' anecdotal Strategemata, emphasising poliorcetics, or the art of siege warfare, but treating magic as a supplement to the military arts; it is "saturated with astrology", remarked Lynn White, Jr. in a review of the first facsimile edition.[2]

History

Konrad Kyeser wrote his treatise between 1402 and 1405 when he was exiled from Prague to his hometown of Eichstätt.[3] Many of the illustrations for the book were made by German illuminators who were sent to Eichstätt after their own ousting from the Prague scriptorium.[4] The work, which was not printed until 1967, survived in a single original presentation manuscript on parchment at University of Göttingen,[5] bearing the date 1405, and in numerous copies, excerpts and amplifications, both of the text and of the illustrations, made in German lands.

Design

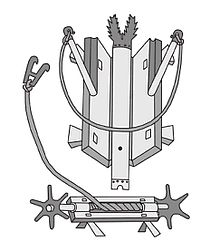

Bellifortis was written in Latin and contained many elaborate illustrations of war weaponry. The manual discusses machines and technology that were old and new. It described weapons such as trebuchets, battering rams, movable portable bridges, cannons, rockets, chariots, ships, mills, scaling ladders, incendiary devices, crossbows, and instruments of torture.[4] The portrait of the author is called by its modern editor the first realistic portrait of an author since Antiquity.[6]

Kyeser’s viewpoint was that warfare in the broadest sense was most effective if looked at from all angles, which included astrology and sorcery. His manual presented the technology of the art of war through the association of education and Latin letters. The book was of a large expensive format. It had elaborate illustrations and lavish drawings of a large number of war devices and machines. The treatise was designed more for a prince or king than for an engineer. Kyeser believed his war manual would make other armies run in all directions.[3]

His treatise often made reference to antiquity, especially the war tactics of Alexander the Great. He writes that Alexander had many war technical abilities. In one illustration he shows Alexander with a giant spearhead-like artifact in his hands with the mysterious letters: MEUFATON. In another illustration Alexander is shown as the supposed inventor of a very large war carriage. Kyeser writes that Alexander was not only a great inventor of war devices but was able to use them himself. Alexander is portrayed with magical abilities.[3]

Dedication

Konrad dedicated his finished treatise to the weak Ruprecht III in a bitter response to his exile. He emphasizes in the dedication the relationship of technical knowledge to technical skills. He writes of the German soldiers, "Just as the sky shines with stars, Germany shines forth with liberal disciplines, is embellished with mechanics, and adorned with diverse arts."[3]

At the end of the treatise, Kyeser gives a markedly unusual appearance of himself. He portrays himself as a dying worried person. He even provides his own epitaph, "May my soul be joined to your very high one."[3]

Legacy

The Bellifortis is survived in 45 manuscripts and was either copied completely or partly, and sometimes amplified, in several later manuscripts. The most famous are the Thott manuscript of Hans Talhoffer of the 15th century,[citation needed] but there are editions of Vegetius' De Re Militari from 1535 in Latin[7] and 1536 in French,[8] that contain pictures clearly copied from the Bellifortis (with more up-to-date clothing for the soldiers), to augment the original text-only treatise by Vegetius. In the Renaissance in Italy Bellifortis was well-known and widespread. The result of new research shows that also Leonardo da Vinci knew the work of Kyeser and that several of Leonardos technical illustrations are based on the Bellifortis.[9]

Notes

- ^ Anzovin, Steven et al, Famous First Facts, International Edition — A Record of First Happenings, Discoveries, and Inventions in World History, H. W. Wilson Company (2000), p. 263 item 4117: "The first illustrated manual of military technology was Bellifortis, written and illustrated by Conrad Kyeser of Eichstatt, Germany, and covering a thousand years of European weaponry."

- ^ Conrad Kyeser aus Eichstätt, Bellifortis, vol. I, facsimile edition in color, edited, with German translation, introduction and notes by Götz Quarg (Düsseldorf) 1967; extensively reviewed by Lynn White, Jr, in Technology and Culture, 10,.3 (July 1969: 436–441)

- ^ a b c d e Long, pp. 105–108

- ^ a b Lefèvre, pp. 67–72

- ^ Codex Ms. philos. 63; four early drafts of the finished text (1402–04) also survive.

- ^ Quarg, noted in White (1969:438).

- ^ Fl. Vegetii Renati viri illustris De re militari libri quatuor. Sixti Iulii frontini viri consularis de Strategematis libri totidem. Aeliani de instruendis Aciebus liber unus. Modesti de vocabulis rei militaris liber unus. Item pictura bellicae cxx passim Vegetio adjectae. Collata sunt omnia ad antiquos codices, maximè B V D AE I, quod testabitur Aelianus. Parisiis : Christiani Wecheli, 1 vol. ([8]-279-[1] p.) : ill. ; in-fol, 1535, Read online

- ^ Du faict de guerre et fleur de chevalerie, quatre livres, Flavius Vegetius Renatus Vegèce, chez Chrestien Wechel, Paris 1536 Read online (pictures only)

- ^ Marc van den Broek (2019), Leonardo da Vinci Spirits of Invention. A Search for Traces, Hamburg: A.TE.M., ISBN 978-3-00-063700-1

Bibliography

- Anzovin, Steven et al., Famous First Facts, International Edition — A Record of First Happenings, Discoveries, and Inventions in World History, H. W. Wilson Company (2000), ISBN 0-8242-0958-3

- Marc van den Broek, Leonardo da Vincis Erfindungsgeister. Eine Spurensuche, Mainz, 2018, ISBN 978-3-961760-45-9

- Lefèvre, Wolfgang, Picturing Machines 1400–1700, MIT Press, 2004, ISBN 0-262-12269-3

- Long, Pamela O., Openness, Secrecy, Authorship: Technical Arts and the Culture of Knowledge from Antiquity to the Renaissance, JHU Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8018-6606-5

- Regina Cermann: Astantes stolidos sic immutabo stultos - Von nachlässigen Schreibern und verständigen Buchmalern. Zum Zusammenspiel von Text und bild in Konrad Kyesers Bellifortis. In: Wege zum illuminierten Buch. Herstellungsbedingungen für Buchmalerei in Mittelalter und früher Neuzeit. Wien 2014, S. 148-176, ISBN 978-3-205-79491-2, Online: https://e-book.fwf.ac.at/detail_object/o:521

External links

![]() Media related to Bellifortis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bellifortis at Wikimedia Commons