Bolsover Castle

| Bolsover Castle | |

|---|---|

Bolsover Castle seen from below with the Little Castle protruding above the rest of the castle | |

| General information | |

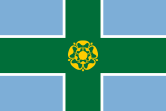

| Town or city | Bolsover, Derbyshire |

| Country | England, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 53°13′53″N 1°17′49″W / 53.23139°N 1.29694°W |

| Official name | Bolsover Castle |

| Designated | 9 October 1981 |

| Reference no. | 1012496[1] |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 23 March 1989 |

| Reference no. | 1108976[2] |

Bolsover Castle is in the town of Bolsover, (grid reference SK471707), in the north-east of the English county of Derbyshire. Built in the early 17th century, the present castle lies on the earthworks and ruins of the 12th-century medieval castle; the first structure of the present castle was built between 1612 and 1617 by Sir Charles Cavendish.[3] The site is now in the care of the English Heritage charity, as both a Grade I listed building[2] and a Scheduled Ancient Monument.[1]

History

Medieval

The original castle was built by the Peverel family in the 12th century and became Crown property in 1155 when William Peverel the Younger died. The Ferrers family who were Earls of Derby laid claim to the Peveril property.[4]

When a group of barons led by King Henry II's sons – Henry the Young King, Geoffrey Duke of Brittany, and Prince Richard, later Richard the Lionheart – revolted against the king's rule, Henry spent £116 on building at the castles of Bolsover and Peveril in Derbyshire.[5][6] The garrison was increased to a force led by 20 knights and was shared with the castles of Peveril and Nottingham during the revolt.[5] King John ascended the throne in 1199 after his brother Richard's death. William de Ferrers maintained the claim of the Earls of Derby to the Peveril estates. He paid John 2000 marks for the lordship of the Peak, but the Crown retained possession of Bolsover and Peveril Castles. John finally gave them to Ferrers in 1216 to secure his support in the face of country-wide rebellion. However, the castellan Brian de Lisle refused to hand them over. Although Lisle and Ferrers were both John's supporters, John gave Ferrers permission to use force to take the castles. The situation was still chaotic when Henry III became king after his father's death in 1216. Bolsover fell to Ferrers' forces in 1217 after a siege.[7]

The castle was returned to crown control in 1223, at which point £33 was spent on repairing the damage the Earl of Derby had caused when capturing the castle six years earlier. Over the next 20 years, four towers were added, the keep was repaired, various parts of the curtain wall were repaired, and a kitchen and barn were built, all at a cost of £181. From 1290 onward, the castle and its surrounding manor were granted to a series of local farmers. Under their custodianship, the castle gradually fell into a state of disrepair.[8]

Post-medieval

Bolsover castle was granted to George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury, by King Edward VI in 1553. Following Shrewsbury’s death in 1590, his son Gilbert, 7th Earl of Shrewsbury, sold the ruins of Bolsover Castle to his step-brother and brother-in-law Sir Charles Cavendish, who wanted to build a new castle on the site.[9] Working with the famous builder and designer Robert Smythson, Cavendish’s castle was designed for elegant living rather than defence, and was unfinished at the time of the two men’s deaths, in 1614 and 1617 respectively.[10] Accounts survive for building the early stages of the "Little Castle." Unusually for this period female labour was recorded, and the women's names or husband's names are given.[11][12]

The building of the castle was continued by Cavendish’s two sons, William and John, who were influenced by the Italian-inspired work of the architect Inigo Jones.[9] The tower, known today as the 'Little Castle', was completed around 1621.[13] Construction was interrupted by the Civil Wars of 1642 to 1651, during which the castle was taken by the Parliamentarians, who slighted it, when it fell into a ruinous state. William Cavendish, who was created Marquess of Newcastle in 1643 and Duke of Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1665, added a new hall and staterooms to the Terrace Range, and by the time of his death in 1676 the castle had been restored to good order.[13] The main usage of the building extended over twenty years, and it is presumed that the family lived at the castle towards the end of that period.[14] It then passed through Margaret Bentinck, Duchess of Portland into the Bentinck family, and ultimately became one of the seats of the Earls and Dukes of Portland. After 1883, the castle was uninhabited, and in 1945 it was given to the nation by the 7th Duke of Portland. The castle is now in the care of English Heritage.[13]

Bolsover Castle is a Scheduled Ancient Monument,[1][15] a "nationally important" historic building and archaeological site which has been given protection against unauthorised change.[16] It is also a Grade I listed building (first listed in 1985)[2][17] and recognised as an internationally important structure.[18]

-

The exterior of the long gallery

-

The Little Castle at Bolsover

-

Model of Bolsover Castle as it may have looked in the late 1600s

Haunting

The television paranormal investigation show Most Haunted investigated the castle as part of their five-night 2007 Halloween live event for Living TV, with presenter Yvette Fielding joined by medium David Wells and parapsychologist Ciarán O'Keeffe on location in the castle.[citation needed]

In 2017 the site was voted the spookiest site by English Heritage staff. Mysterious footsteps, a boy holding visitors' hands, muffled voices and unexplained lights are among the events reported to have occurred.[19]

TV and film location

The 2008 film Summer was filmed on the castle grounds.[citation needed] Antiques Roadshow was held there in July 2015.[20]

References

- ^ a b c Historic England. "Bolsover Castle: eleventh century motte and bailey castle, twelfth century tower keep castle and seventeenth century country house (1012496)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ a b c Historic England. "Bolsover Castle (Grade I) (1108976)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Bolsover Castle. London: English Heritage. 2014. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-84802-111-2.

- ^ "Bolsover". A Topographical Dictionary of England (1848). British History Online. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ^ a b Eales 2006, p. 23

- ^ Colvin & Brown 1963, p. 572

- ^ Eales 2006, p. 24

- ^ Colvin & Brown 1963, p. 573

- ^ a b Worsley, Lucy (2001). Bolsover Castle. London: English Heritage. pp. 2–3. ISBN 1-85074-762-8.

- ^ George Hall, The history of Chesterfield; with particulars of the hamlets contiguous to the town, and descriptive accounts of Chatsworth, Hardwick, and Bolsover Castle (1839), pp. 470-471.

- ^ Mark Girouard, Robert Smythson & the Elizabethan Country House (London, 1983), p. 234.

- ^ Douglas Knoop & Gwilyn Peredur Jones, 'The Bolsover Castle Building Account, 1613', Ars Quatuor Coronatorum, 49:1 (London 1936), pp. 15-6

- ^ a b c Fry 1980

- ^ Riden, Philip (2008). Bolsover: castle, town and colliery. London: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-86077-484-3.

- ^ "Bolsover Castle", Pastscape, Historic England, retrieved 2012-04-17

- ^ "Scheduled Monuments", Pastscape, Historic England, retrieved 2012-04-17

- ^ Bolsover Castle, Heritage Gateway, retrieved 2012-04-17

- ^ "Frequently asked questions", Images of England, Historic England, archived from the original on 2007-11-11, retrieved 2012-04-17

- ^ "Ghostly boy seen by staff at 'spookiest' English Heritage site". ITV. 17 October 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ Smith, Matthew (9 July 2015). "Thousands flock to BBC Antiques Roadshow filming at Bolsover Castle". Mansfield and Ashfield Chad. JPIMedia Publishing Ltd. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- Bibliography

- Colvin, H. M.; Brown, R. A. (1963), "The Royal Castles 1066–1485", The History of the King's Works. Volume II: The Middle Ages, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, pp. 553–894

- Eales, Richard (2006), Peveril Castle, London: English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-85074-982-0

- Fry, Plantagenet Somerset (1980), The David & Charles Book of Castles, David & Charles, ISBN 978-0-7153-7976-9

Further reading

- Worsley, Lucy (2010) [2000], Bolsover Castle (revised ed.), London: English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-85074-762-8

- Worsley, Lucy (May 2004). "Changing Notions of Authenticity: Presenting a Castle Over Four Centuries". International Journal of Heritage Studies. 10 (2): 129–149. doi:10.1080/13527250410001692868.

External links

- Bolsover Castle page on English Heritage's official site

- Photographs around the Castle

- Bolsover Castle on Google Arts & Culture

- The Elysium Closet on Google Arts & Culture