Common snapping turtle

| Common snapping turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female searching for nest site | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Family: | Chelydridae |

| Genus: | Chelydra |

| Species: | C. serpentina

|

| Binomial name | |

| Chelydra serpentina | |

| |

| Native range map of C. serpentina | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) is a species of large freshwater turtle in the family Chelydridae. Its natural range extends from southeastern Canada, southwest to the edge of the Rocky Mountains, as far east as Nova Scotia and Florida. The three species of Chelydra and the larger alligator snapping turtles (genus Macrochelys) are the only extant chelydrids, a family now restricted to the Americas. The common snapping turtle, as its name implies, is the most widespread.[2]

The common snapping turtle is noted for its combative disposition when out of the water with its powerful beak-like jaws, and highly mobile head and neck (hence the specific epithet serpentina, meaning "snake-like"). In water, it is likely to flee and hide underwater in sediment. The common snapping turtle has a life-history strategy characterized by high and variable mortality of embryos and hatchlings, delayed sexual maturity, extended adult longevity, and iteroparity (repeated reproductive events) with low reproductive success per reproductive event.[3]

Females, and presumably also males, in more northern populations mature later (at 15–20 years) and at a larger size than in more southern populations (about 12 years). Lifespan in the wild is poorly known, but long-term mark-recapture data from Algonquin Park in Ontario, Canada, suggest a maximum age over 100 years.[3]

Anatomy and morphology

C. serpentina has a rugged, muscular build with a ridged carapace (upper shell), although ridges tend to be more pronounced in younger individuals. The carapace length in adulthood may be nearly 50 cm (20 in), though 25–47 cm (9.8–18.5 in) is more common.[4] C. serpentina usually weighs 4.5–16 kg (9.9–35.3 lb). Per one study, breeding common snapping turtles were found to average 28.5 cm (11.2 in) in carapace length, 22.5 cm (8.9 in) in plastron length and weigh about 6 kg (13 lb).[5]

Males are larger than females, with almost all weighing in excess of 10 kg (22 lb) being male and quite old, as the species continues to grow throughout life.[6] Any specimen above the aforementioned weights is exceptional, but the heaviest wild specimen caught reportedly weighed 34 kg (75 lb). Snapping turtles kept in captivity can be quite overweight due to overfeeding and have weighed as much as 39 kg (86 lb). In the northern part of its range, the common snapping turtle is often the heaviest native freshwater turtle.[7]

Ecology and life history

Common habitats are shallow ponds or streams. Some may inhabit brackish environments, such as estuaries. These sources of water tend to have an abundance of aquatic vegetation due to the shallow pools.[8] Common snapping turtles sometimes bask—though rarely observed—by floating on the surface with only their carapaces exposed, though in the northern parts of their range, they also readily bask on fallen logs in early spring. In shallow waters, common snapping turtles may lie beneath a muddy bottom with only their heads exposed, stretching their long necks to the surface for an occasional breath. Their nostrils are positioned on the very tip of the snout, effectively functioning as snorkels.[9]

Snapping turtles are omnivorous. Important aquatic scavengers, they are also active hunters that use ambush tactics to prey on anything they can swallow, including many invertebrates, fish, frogs, reptiles (including snakes and smaller turtles), unwary birds, and small mammals.[10] In some areas adult snapping turtles can occasionally be incidentally detrimental to breeding waterfowl, but their effect on such prey as ducklings and goslings is frequently exaggerated.[9] As omnivorous scavengers though, they will also feed on carrion and a surprisingly large amount of aquatic vegetation.[11]

Common snapping turtles have few predators when older, but eggs are subject to predation by crows, American mink, skunks, foxes, and raccoons. As hatchlings and juveniles, most of the same predators will attack them as well as herons (mostly great blue herons), bitterns, hawks, owls, fishers, American bullfrogs, large fish, and snakes.[7] There are records during winter in Canada of hibernating adult common snapping turtles being ambushed and preyed on by northern river otters.[6] Other natural predators which have reportedly preyed on adults include coyotes, American black bears, American alligators and their larger cousins, alligator snapping turtles.[12] Large, old male snapping turtles have very few natural threats due to their formidable size and defenses, and tend to have a very low annual mortality rate.[6]

These turtles travel extensively over land to reach new habitats or to lay eggs. Pollution, habitat destruction, food scarcity, overcrowding, and other factors drive snappers to move; it is quite common to find them traveling far from the nearest water source. Experimental data supports the idea that snapping turtles can sense the Earth's magnetic field, which could also be used for such movements (together with a variety of other possible orientation cues).[13][14]

This species mates from April through November, with their peak laying season in June and July. The female can hold sperm for several seasons, using it as necessary. Females travel over land to find sandy soil in which to lay their eggs, often some distance from the water. After digging a hole, the female typically deposits 25 to 80 eggs each year, guiding them into the nest with her hind feet and covering them with sand for incubation and protection.[15]

Incubation time is temperature-dependent, ranging from 9 to 18 weeks. One study on the incubation period of the common snapping turtle incubated the eggs at two temperatures: 20 °C (68 °F) and 30 °C (86 °F). The research found that the incubation period at the higher temperature was significantly shorter at approximately 63 days, while at the lower temperature the time was approximately 140 days.[16] In cooler climates, hatchlings overwinter in the nest. The common snapping turtle is remarkably cold-tolerant; radiotelemetry studies have shown some individuals do not hibernate, but remain active under the ice during the winter.[15]

Common snapping turtle hatchlings have recently been found to make sounds before nest exit onto the surface, a phenomenon also known from species in the South American genus Podocnemis and the Ouachita map turtle. These sounds are mostly "clicking" noises, but other sounds, including those that sound somewhat like a “creak” or rubbing a finger along a fine-toothed comb, are also sometimes produced.[17][18]

In the northern part of their range snapping turtles do not breathe for more than six months because ice covers their hibernating site. These turtles can get oxygen by pushing their head out of the mud and allowing gas exchange to take place through the membranes of their mouth and throat. This is known as extrapulmonary respiration.[19]

If they cannot get enough oxygen through this method they start to utilize anaerobic pathways, burning sugars and fats without the use of oxygen. The metabolic by-products from this process are acidic and create very undesirable side effects by spring, which are known as oxygen debt.[19] Although designated as "least concern" on the IUCN redlist, the species has been designated in the Canadian part of its range as "Special Concern" due to its life history being sensitive to disruption by anthropogenic activity.[20]

Systematics and taxonomy

Currently, no subspecies of the common snapping turtle are recognized.[21] The former Florida subspecies osceola is currently considered a synonym of serpentina, while the other former subspecies Chelydra rossignonii[22] and Chelydra acutirostris are both recognized as full species.[21][23]

Behavior

In their environment, they are at the top of the food chain, causing them to feel less fear or aggression in some cases. When they encounter a species unfamiliar to them such as humans, in rare instances, they will become curious and survey the situation and even more rarely may bump their nose on a leg of the person standing in the water. Although snapping turtles have fierce dispositions,[24] when they are encountered in the water or a swimmer approaches, they will slip quietly away from any disturbance or may seek shelter under mud or grass nearby.[25]

Relationship with humans

As food

The common snapping turtle is a traditional ingredient in turtle soup; consumption in large quantities, however, can become a health concern due to potential concentration of toxic environmental pollutants in the turtle's flesh.[26]

Captivity

The common snapping turtle is not an ideal pet. Its neck is very flexible, and a wild turtle can bite its handler even if picked up by the sides of its shell. The claws are as sharp as those of bears and cannot be trimmed as can dog claws. The turtle uses its paws like a bear for hunting and slicing food, while biting it. Despite this, a snapping turtle cannot use its claws for either attacking (its legs have no speed or strength in "swiping" motions) or eating (no opposable thumbs), but only as aids for digging and gripping. Veterinary care is best left to a reptile specialist. A wild common snapping turtle will make a hissing sound when it is threatened or encountered, but they prefer not to provoke confrontations.[27]

It is a common misconception that common snapping turtles may be safely picked up by the tail with no harm to the animal; in fact, this has a high chance of injuring the turtle, especially the tail itself and the vertebral column.[28] Lifting the turtle with the hands is difficult and dangerous. Snappers can stretch their necks back across their own carapace and to their hind feet on either side to bite. When they feel stressed, they release a musky odor from behind their legs.

It may be tempting to rescue a snapping turtle found on a road by getting it to bite a stick and then dragging it out of immediate danger. This action can, however, severely scrape the legs and underside of the turtle and lead to deadly infections in the wounds. The safest way to pick up a common snapping turtle is by grasping the carapace behind the back legs, being careful to not grasp the tail. There is a large gap behind the back legs that allows for easy grasping of the carapace and keeps hands safe from both the beak and claws of the turtle. It can also be picked up with a shovel, from the back, making sure the shovel is square across the bottom of the shell. The easiest way, though, is with a blanket or tarp, picking up the corners with the turtle in the middle.[citation needed]

Snapping turtles are raised on some turtle farms in Mainland China.[29]

In politics

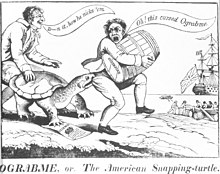

The common snapping turtle was the central feature of a famous American political cartoon. Published in 1808 in protest at the Jeffersonian Embargo Act of 1807, the cartoon depicted a snapping turtle, jaws locked fiercely to an American trader who was attempting to carry a barrel of goods onto a British ship. The trader was seen whimsically uttering the words "Oh! this cursed Ograbme" ("embargo" spelled backwards, and also "O, grab me" as the turtle is doing). This piece is widely considered a pioneering work within the genre of the modern political cartoon.[citation needed]

In 2006, the common snapping turtle was declared the state reptile of New York by vote of the New York Legislature after being chosen by the state's public elementary school children.[30]

Reputation

While it is widely rumored that common snapping turtles can bite off human fingers or toes, and their powerful jaws are more than capable of doing so, no proven cases have ever been presented for this species, as they use their overall size and strength to deter would-be predators.[31] Common snapping turtles are "quite docile" animals underwater that prefer to avoid confrontations rather than provoke them.[31]

In 2002, a study done in the Journal of Evolutionary Biology found that the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) registered between 208 and 226 Newtons of force when it came to jaw strength. In comparison, the average bite force of a human (molars area) is between 300 and 700 Newtons.[32][33] Another non-closely related species known as the alligator snapping turtle has been known to bite off fingers, and at least three documented cases are known.[34]

Invasive species

In recent years in Italy, large mature adult C. serpentina turtles have been taken from bodies of water throughout the country. They were most probably introduced by the release of unwanted pets. In March 2011, an individual weighing 20 kg (44 lb) was captured in a canal near Rome;[35] another individual was captured near Rome in September 2012.[36]

In Japan, the species was introduced as an exotic pet in the 1960s; it has been recorded as the source of serious bite injuries.[citation needed] In 2004 and 2005, some 1,000 individuals were found in Chiba Prefecture, making up the majority of individuals believed to have been introduced.[37]

Conservation

The species is currently classified as Least Concern by the IUCN, but has declined sufficiently due to pressure from collection for the pet trade and habitat degradation that Canada and several U.S. states have enacted or are proposing stricter conservation measures.[1] In Canada, it is listed as "Special Concern" in the Species at Risk Act in 2011 and is a target species for projects that include surveys, identification of major habitats, investigation and mitigation of threats, and education of the public including landowners. Involved bodies include governmental departments, universities, museums, and citizen science projects.[38]

Although Common snapping turtles are listed as a species of least concern, anthropogenic factors still may have major effects on populations. Decades of road mortality may cause severe population decline in common snapping turtle populations present in urbanized wetlands. A study in southwestern Ontario monitored a population near a busy roadway and found a loss of 764 individuals in only 17 years. The population decreased from 941 individuals in 1985 to 177 individuals in 2002. Road mortality may put common snapping turtle populations at risk of extirpation. Exclusion fencing could aid in decreasing population loss.[39]

References

- ^ a b van Dijk, P.P. (2016) [errata version of 2012 assessment]. "Chelydra serpentina ". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012: e.T163424A97408395. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012.RLTS.T163424A18547887.en. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Ernst, C.H. (2008). "Systematics, Taxonomy, and Geographic Distribution of the Snapping Turtles, Family Chelydridae". In A.C. Styermark; M.S. Finkler; R.J. Brooks (eds.). Biology of the Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 5–13.

- ^ a b "COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Snapping Turtle Chelydra serpentina" (PDF).

- ^ Wilson, D.E.; Burnie, D., eds. (2001). Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. London and New York: Dorling Kindersley (DK) Publishing. 624 pp. ISBN 978-0-7894-7764-4.

- ^ Iverson, J.B.; Higgins, H.; Sirulnik, A.; Griffiths, C. (1997). "Local and geographic variation in the reproductive biology of the snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina)". Herpetologica 53 (1): 96-117.

- ^ a b c Brooks, R.J.; Brown, G.P.; Galbraith, D.A. (1991). "Effects of a sudden increase in natural mortality of adults on a population of the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina)". Canadian Journal of Zoology 69 (5): 1314-1320.

- ^ a b Virginia Herpetological Society: Eastern Snapping Turtle Chelydra serpentina serpentina

- ^ Piczak, Morgan L.; Chow-Fraser, Patricia (2019-06-01). "Assessment of critical habitat for common snapping turtles (Chelydra serpentina) in an urbanized coastal wetland". Urban Ecosystems. 22 (3): 525–537. doi:10.1007/s11252-019-00841-1. ISSN 1573-1642. S2CID 78091420.

- ^ a b Hammer, D.A. (1972). Ecological relations of waterfowl and snapping turtle populations. Ph.D. dissertation, Utah State University, Salt Lake City, UT. 72 pg.

- ^ Bergeron, Christine M.; Husak, Jerry E.; Unrine, Jason M.; Romanek, Christopher S.; Hopkins, William A. (August 2007). "Influence of feeding ecology on blood mercury concentrations in four species of turtles". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 26 (8): 1733–1741. doi:10.1897/06-594r.1. ISSN 0730-7268. PMID 17702349. S2CID 19542536.

- ^ "Chelydra serpentina (Common Snapping Turtle)".

- ^ Ernst, C.H., & Lovich, J. E. (2009). Turtles of the United States and Canada. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Landler, Lukas; Painter, Michael S.; Youmans, Paul W.; Hopkins, William A.; Phillips, John B. (2015-05-15). "Spontaneous Magnetic Alignment by Yearling Snapping Turtles: Rapid Association of Radio Frequency Dependent Pattern of Magnetic Input with Novel Surroundings". PLOS ONE. 10 (5): e0124728. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1024728L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124728. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4433231. PMID 25978736.

- ^ Congdon, Justin D.; Pappas, Michael J.; Krenz, John D.; Brecke, Bruce J.; Schlenner, Meredith (2015-02-27). "Compass Orientation During Dispersal of Freshwater Hatchling Snapp Turtles (Chelydra serpentina) and Blanding's Turtles (Emydoidea blandingii)". Ethology. 121 (6): 538–547. doi:10.1111/eth.12366. ISSN 0179-1613.

- ^ a b "US Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Research and Development Center, Environmental Laboratory: Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina)". Archived from the original on 2013-03-31. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- ^ Yntema, C. L. (June 1968). "A series of stages in the embryonic development ofChelydra serpentina". Journal of Morphology. 125 (2): 219–251. doi:10.1002/jmor.1051250207. ISSN 0362-2525. PMID 5681661. S2CID 37022680.

- ^ Geller, G.A.; Casper, G.S. (2019). "Late term embryos and hatchlings of Ouachita Map Turtles (Graptemys ouachitensis) make sounds within the nest". Herpetological Review. 50 (3): 449–452.

- ^ Geller, G.A.; Casper, G.S. (2019). "Chelydra serpentina (Snapping Turtle) hatchling sounds". Herpetological Review. 50 (4): 768–769.

- ^ a b Edqvist, ULf. "Tortoise Trust Web - Conservation and Ecology of Snapping Turtles". www.tortoisetrust.org. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ COSEWIC. "Species Profile - Snapping Turtle". Species At Risk Public Registry. Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 10 June 2013. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ a b Rhodin, Anders G.J.; van Dijk, Peter Paul; Iverson, John B.; Shaffer, H. Bradley (2010-12-14). Turtles of the world, 2010 update: Annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution and conservation status (PDF). Vol. 5. p. 000.xx. doi:10.3854/crm.5.000.checklist.v3.2010. ISBN 978-0965354097. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ van Dijk, P.P.; Lee, J.; Calderón Mandujano, R.; Flores-Villela, O.; Lopez-Luna, M.A.; Vogt, R.C. (2007). "Chelydra rossignoni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2007. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ^ Chelydra, Reptile Database

- ^ Snapping Turtle, Encyclopedia.com

- ^ Common Snapping Turtle, Nature.ca

- ^ "Common Snapping Turtle: Interesting Facts". Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, State of Connecticut. DEEP (ct.gov). 8 November 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ PlusPets Staff. (2020, October 24). Snapping Turtles: A Guide to Owning This Difficult Turtle Breed. PlusPets. http://pluspets.com/snapping-turtles/

- ^ Indiviglio, Frank (2008-06-24). "Handling Snapping Turtles, Chelydra serpentina, and Other Large Turtles". That Reptile Blog. That Pet Place. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- ^ Fang Anning (方安宁), "“小庭院”养殖龟鳖大有赚头 Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine" (Small-scale turtle farming may be very profitable). Zuojiang Daily (左江日报) (with photo)

- ^ Medina, Jennifer (2006-06-23). "A Few Things Lawmakers Can Agree On". N.Y./Region. New York Times. Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- ^ a b Kiley Briggs (July 11, 2018). "Snappers: The myth vs the turtle". The Orianne Society. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ "7 things you need to know about snapping turtles". CBC News. June 16, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ A. Herrel, J. C. O'Reilly, A. M. Richmond (2002). "Evolution of bite performance in turtles". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 15 (6): 1083–1094. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00459.x. S2CID 54067445.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ J. Whitfield Gibbons (June 24, 2018). "Can a Snapping Turtle bite off a finger?". University of Georgia. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ "Una "azzanatrice" catturata fuori Roma". (March 17, 2011). Corriere della Sera. Milan.

- ^ "Tartaruga azzannatrice presa nel Tevere - Photostory Curiosità - ANSA.it". www.ansa.it. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Desaki, Yotaro (5 August 2014). "Invasive snapping turtles on the rise in Chiba, other areas". thejapantimes news. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ Environment and Climate Change Canada (2016). Management Plan for the Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina) in Canada [Proposed] (PDF). Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series. Ottawa: Ottawa, Environment and Climate Change Canada.

- ^ Piczak, Morgan L.; Markle, Chantel E.; Chow-Fraser, Patricia (November 2019). "Decades of Road Mortality Cause Severe Decline in a Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina) Population from an Urbanized Wetland". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 18 (2): 231–240. doi:10.2744/CCB-1345.1. ISSN 1071-8443. S2CID 209338553.

External links

- The Snapping Turtle Page - www.chelydra.org

- Video: How to Help a Snapping Turtle Cross a Road, Toronto Zoo

- Snapping Turtle, Reptiles and Amphibians of Iowa

Further reading

- Behler JL, King FW (1979). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 743 pp. ISBN 0-394-50824-6. (Chelydra serpentina, pp. 435–436 + Plates 322–324).

- Conant R (1975). A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America, Second Edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. xviii + 429 pp. + Plates 1-48. ISBN 0-395-19979-4 (hardcover), ISBN 0-395-19977-8 (paperback). (Chelydra serpentina, pp. 37–38 + Plates 5, 11 + Map3).

- Goin CJ, Goin OB, Zug GR (1978). Introduction to Herpetology, Third Edition. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company. xi + 378 pp. ISBN 0-7167-0020-4. (Chelydra serpentina, pp. 122, 142, 258).

- Linnaeus C (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, diferentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio Decima, Reformata. Stockholm: L. Salvius. 824 pp. (Testudo serpentina, new species, p. 199). (in Latin).

- Smith HM, Brodie ED Jr (1982). Reptiles of North America: A Guide to Field Identification. New York: Golden Press. 240 pp. ISBN 0-307-13666-3. (Chelydra serpentina, pp. 38–39).

- Zim HS, Smith HM (1956). Reptiles and Amphibians: A Guide to Familiar American Species: A Golden Nature Guide. New York: Simon and Schuster. 160 pp. (Chelydra serpentina, pp. 19, 24, 155).

- Amtyaz Safi, Hashmi MUA and Smith JP. 2020. A review of distribution, threats, conservation and status of freshwater turtles of Ontario, Canada. Journal of Environmental sciences. 2(1) (2020): 36–41.