Cruelty to animals

| Part of a series on |

| Animal rights |

|---|

Cruelty to animals, also called animal abuse, animal neglect or animal cruelty, is the infliction by omission (neglect) or by commission by humans of suffering or harm upon any non-human animal. More narrowly, it can be the causing of harm or suffering for specific achievement, such as killing animals for entertainment; cruelty to animals sometimes encompasses inflicting harm or suffering as an end in itself, defined as zoosadism.

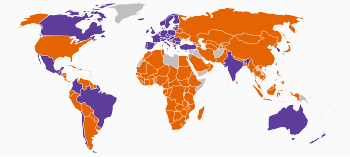

Divergent approaches to laws concerning animal cruelty occur in different jurisdictions throughout the world. For example, some laws govern methods of killing animals for food, clothing, or other products, and other laws concern the keeping of animals for entertainment, education, research, or pets. There are a number of conceptual approaches to the issue of cruelty to animals.

Some think that the animal welfare position holds that there is nothing inherently wrong with using animals for human purposes, such as food, clothing, entertainment, fun and research, but that it should be done in a way that minimizes unnecessary pain and suffering, sometimes referred to as "humane" treatment.[citation needed] Others have argued that the definition of 'unnecessary' varies widely and could include virtually all current use of animals.

Utilitarian advocates argue from the position of costs and benefits and vary in their conclusions as to the allowable treatment of animals. Some utilitarians argue for a weaker approach which is closer to the animal welfare position, whereas others argue for a position that is similar to animal rights. Animal rights theorists criticize these positions, arguing that the words "unnecessary" and "humane" are subject to widely differing interpretations, and that animals have basic rights. They say that most animal use itself is unnecessary and a cause of suffering, so the only way to ensure protection for animals is to end their status as property and to ensure that they are never used as a substance or as a non-living thing.

Definition and viewpoints

Template:World laws pertaining to animal sentience

Throughout history, some individuals, like Leonardo da Vinci for example, who once purchased caged birds in order to set them free,[1][2] were concerned about cruelty to animals. His notebooks also record his anger with the fact that humans used their dominance to raise animals for slaughter.[3] According to contemporary philosopher Nigel Warburton, for most of human history the dominant view has been that animals are there for humans to do with as they see fit.[1]

René Descartes believed that non-humans are automata — complex machines with no soul, mind, or reason.[4] In Cartesian dualism, consciousness was unique to human among all other animals and linked to physical matter by divine grace. However, close analysis shows that many human features such as complex sign usage, tool use, and self-consciousness can be found in some animals.[5]

Charles Darwin, by presenting the theory of evolution, revolutionized the way that humans viewed their relationship with other species. Darwin believed that not only did human beings have a direct kinship with other animals, but the latter had social, mental and moral lives too. Later, in The Descent of Man (1871), he wrote: "There is no fundamental difference between man and the higher mammals in their mental faculties."[6]

Modern philosophers and intellectuals, such as Peter Singer and Tom Regan, have argued that animals' ability to feel pain as humans do makes their well-being worthy of equal consideration.[7] There are many precursors of this train of thought. Jeremy Bentham, the founder of utilitarianism, famously wrote in his An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789):[8]

"The question is not, can they reason nor can they talk? but, can they suffer?"

These arguments have prompted some to suggest that animals' well-being should enter a social welfare function directly, not just indirectly via its effect only on human well-being.[9] Many countries have now formally recognized animal sentience and animal suffering, and have passed anti-cruelty legislation in response.

Forms

Animal cruelty can be broken down into two main categories: active and passive. Passive cruelty is typified by cases of neglect, in which the cruelty is a lack of action rather than the action itself. Oftentimes passive animal cruelty is accidental, born of ignorance. In many cases of neglect in which an investigator believes that the cruelty occurred out of ignorance, the investigator may attempt to educate the pet owner, then revisit the situation. In more severe cases, exigent circumstances may require that the animal be removed for veterinary care.[10]

Industrial animal farming

Farm animals are generally produced in large, industrial facilities that house thousands of animals at high densities; these are sometimes called factory farms. The industrial nature of these facilities means that many routine procedures or animal husbandry practices impinge on the welfare of the animals and could be considered as cruelty, with Henry Stephen Salt claiming in 1899 that "it is impossible to transport and slaughter vast numbers of large and highly-sensitive animals in a really humane manner".[11] It has been suggested the number of animals hunted, kept as companions, used in laboratories, reared for the fur industry, raced, and used in zoos and circuses, is insignificant compared to farm animals, and therefore the "animal welfare issue" is numerically reducible to the "farm animal welfare issue".[12] Similarly, it has been suggested by campaign groups that chickens, cows, pigs, and other farm animals are among the most numerous animals subjected to cruelty. For example, because male chickens do not lay eggs, newly hatched males are culled using macerators or grinders.[13][14] Worldwide meat overconsumption is another factor that contributes to the miserable situation of farm animals.[15] Many undercover investigators have exposed the animal cruelty taking place inside the factory farming industry and there is evidence to show that consumers provided with accurate information about the process of meat productions and the abuse that accompanies it has led to changes in their attitudes.[16]

The American Veterinary Medical Association accepts maceration subject to certain conditions, but recommends alternative methods of culling as more humane.[17][18] Egg-laying hens are then transferred to "battery cages" where they are kept in high densities. Matheny and Leahy attribute osteoporosis in hens to this caging method.[12] Broiler chickens suffer similar situations, in which they are fed steroids to grow at a super-fast speed, so fast that their bones, heart and lungs often cannot keep up. Broiler chickens under six weeks old suffer painful crippling due to fast growth rates, whilst one in a hundred of these very young birds dies of heart failure.[19]

To reduce aggression in overcrowded conditions, shortly after birth piglets are castrated, their tails are amputated, and their teeth clipped.[5] Calves are sometimes raised in veal crates, which are small stalls that immobilize calves during their growth, reducing costs and preventing muscle development, making the resulting meat a pale color, preferred by consumers.[12]

Animal cruelty such as soring, which is illegal, sometimes occurs on farms and ranches, as does lawful but cruel treatment such as livestock branding. Since Ag-gag laws prohibit video or photographic documentation of farm activities, these practices have been documented by secret photography taken by whistleblowers or undercover operatives from such organizations as Mercy for Animals and the Humane Society of the United States posing as employees. Agricultural organizations such as the American Farm Bureau Federation have successfully advocated for laws that tightly restrict secret photography or concealing information from farm employers.[20]

Welfare concerns of farm animals

The following are lists of invasive procedures which cause pain, routinely performed on farm animals, and housing conditions that routinely cause animal welfare concerns. In one survey of United States homeowners, 68% of respondents said they consider the price of meat a more important issue.[9]

| Species | Invasive procedures | Housing |

|---|---|---|

| Broiler chickens |

| |

| Cattle |

| |

| Dairy Cows |

| |

| Domestic turkey |

|

|

| Dog |

|

|

| Ducks and Goose |

| |

| Egg laying hens |

| |

| Goats and sheep |

| |

| Horses |

| |

| Pigs |

|

|

- ^ 'Desnooding' is the removal of the snood, a fleshy appendage on the forehead of turkeys.

- ^ 'Blinders' or 'spectacles' are included as some versions require a pin to pierce the nasal septum.

- ^ 'Dubbing' is the procedure of removing the comb, wattles and sometimes earlobes of poultry. Removing the wattles is sometimes called "dewattling".

- ^ 'Marking' is the simultaneous mulesing, castration and tail docking of lambs.

- ^ 'Mulesing' is the removal of strips of wool-bearing skin from around the breech (buttocks) of a sheep to prevent flystrike (myiasis)

Alleged link to human violence and psychological disorders

There are studies providing evidence of a link between animal cruelty and violence towards humans.[31][32][33][34] A 2009 study found that slaughterhouse employment increases total arrest rates, arrests for violent crimes, arrests for rape, and arrests for other sex offenses in comparison with other industries.[35]

A history of torturing pets and small animals, a behavior known as zoosadism, is considered one of the signs of certain psychopathologies, including antisocial personality disorder, also known as psychopathic personality disorder. According to The New York Times, "[t]he FBI has found that a history of cruelty to animals is one of the traits that regularly appears in its computer records of serial rapists and murderers, and the standard diagnostic and treatment manual for psychiatric and emotional disorders lists cruelty to animals a diagnostic criterion for conduct disorders."[36] "A survey of psychiatric patients who had repeatedly tortured dogs and cats found all of them had high levels of aggression toward people as well, including one patient who had murdered a young boy."[36] Robert K. Ressler, an agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation's behavioral sciences unit, studied serial killers and noted, "Murderers like this (Jeffrey Dahmer) very often start out by killing and torturing animals as kids."[37]

Acts of intentional animal cruelty or non-accidental injury may be indicators of serious psychological problems.[38][39] According to the American Humane Association, 13% of intentional animal abuse cases involve domestic violence.[40] As many as 71% of pet-owning women seeking shelter at safe houses have reported that their partner had threatened and/or hurt or killed one or more of their pets; 32% of these women reported that one or more of their children had also hurt or killed pets. Battered women report that they are prevented from leaving their abusers because they fear what will happen to the animals in their absence. Animal abuse is sometimes used as a form of intimidation in domestic disputes.[41]

Cruelty to animals is one of the three components of the Macdonald triad, behavior considered to be one of the signs of violent antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. According to the studies used to form this model, cruelty to animals is a common (but not universal) behavior in children and adolescents who grow up to become serial killers and other violent criminals. It has also been found that children who are cruel to animals have often witnessed or been victims of abuse themselves.[42] In two separate studies cited by the Humane Society of the United States, roughly one-third of families suffering from domestic abuse indicated that at least one child had hurt or killed a pet.[43]

Cultural rituals

Many times, when Asiatic elephants are captured in Thailand, handlers use a technique known as the training crush, in which "handlers use sleep-deprivation, hunger, and thirst to 'break' the elephants' spirit and make them submissive to their owners"; moreover, handlers drive nails into the elephants' ears and feet.[44]

The practice of cruelty to animals for divination purposes is found in ancient cultures, and some modern religions such as Santeria continue to do animal sacrifices for healing and other rituals. Taghairm was performed by ancient Scots to summon devils.

Television and filmmaking

Animal cruelty has long been an issue with the art form of filmmaking, with even some big-budget Hollywood films receiving criticism for allegedly harmful—and sometimes lethal—treatment of animals during production. Court decisions have addressed films that harm animal such as videos that in part depict dog fighting.[45]

The American Humane Association (AHA) has been associated with monitoring American film-making since after the release of the film Jesse James (1939), in which a horse was pushed off a plank and drowned in a body of water after having fallen 40 feet into it.[46] Initially, monitoring of animal cruelty was a partnership between the AHA and officials in the Hays Office through the Motion Picture Production Code. Provisions in the code discouraged "apparent cruelty to children and animals", and because the Hays Office had the power to enforce this clause, the American Humane Association (AHA) often had access to sets to assess adherence to it. However, because the American Humane Association's Hollywood office depended on the Hays Office for the right to monitor sets, the closure of the Hays Office in 1966 corresponded with an increase in animal cruelty on movie sets.[47]

In addition, other animal welfare organizations worldwide, have also monitored the use of animals in film.

By 1977, a three-year contract was in place between the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) and the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists which specified that the American Humane Association should be "consulted in the use of animals 'when appropriate'", but the contract did not provide a structure for what "appropriate" meant, and had no enforcement powers. This contract expired in 1980.[48]

One of the most infamous examples of animal cruelty in film was Michael Cimino's flop Heaven's Gate (1980), in which numerous animals were brutalized and even killed during production. Cimino allegedly killed chickens and bled horses from the neck to gather samples of their blood to smear on actors for Heaven's Gate, and also allegedly had a horse blown up with dynamite while shooting a battle sequence, the shot of which made it into the film. This film played a large part in renewed scrutiny of animal cruelty in films, and led to renewed official on-set jurisdiction to monitor the treatment of animals by the AHA in 1980.[46]

After the release of the film Reds (1981), the star and director of the picture, Warren Beatty apologized for his Spanish film crew's use of tripwires on horses while filming a battle scene, when Beatty was not present. Tripwires were used against horses when Rambo III (1988) and The 13th Warrior (1999) were being filmed. An ox was sliced nearly in half during production of Apocalypse Now (1979), while a donkey was bled to death for dramatic effect for the Danish film Manderlay (2005), in a scene later deleted from the film.

There is a case of cruelty to animals in the South Korean film The Isle (2000), according to its director Kim Ki-Duk.[49] In the film, a real frog is skinned alive while fish are mutilated. Seven animals were killed for the camera in the controversial Italian film Cannibal Holocaust (1980).[50] The images in the film include the slow and graphic beheading and ripping apart of a turtle, a monkey being beheaded and its brains being consumed by natives and a spider being chopped apart. Cannibal Holocaust was only one film in a collective of similarly themed movies (cannibal films) that featured unstaged animal cruelty. Their influences were rooted in the films of Mondo filmmakers, which sometimes contained similar content. In several countries, such as the United Kingdom, Cannibal Holocaust was only allowed for release with most of the animal cruelty edited out.[citation needed]

More recently, the video sharing site YouTube has been criticized for hosting thousands of videos of real life animal cruelty, especially the feeding of one animal to another for the purposes of entertainment and spectacle. Although some of these videos have been flagged as inappropriate by users, YouTube has generally declined to remove them, unlike videos which include copyright infringement.[51][52]

The Screen Actors Guild (SAG) has contracted with the American Humane Association (AHA) for monitoring of animal use during filming or while on the set.[53] Compliance with this arrangement is voluntary and only applies to films made in the United States. Films monitored by the American Humane Association may bear one of their end-credit messages. Many productions, including those made in the United States, do not advise AHA or SAG of animal use in films, so there is no oversight.[54]

| Nationwide ban | Partial ban[a] |

| Ban on import/export | No ban |

| Unknown |

- ^ certain animals are excluded or the laws vary internally

Simulations of animal cruelty exist on television, too. On the 23 September 1999 edition of WWE Smackdown!, a plotline had professional wrestler Big Boss Man trick fellow wrestler Al Snow into appearing to eat his pet chihuahua Pepper.[56][57]

Circuses

The use of animals in the circus has been controversial since animal welfare groups have documented instances of animal cruelty during the training of performing animals. Animal abuse in circuses has been documented such as small enclosures, lack of veterinary care, abusive training methods, and lack of oversight by regulating bodies.[58][59] Animal trainers have argued that some criticism is not based on fact, including beliefs that shouting makes the animals believe the trainer is going to hurt them, that caging is cruel and common, and the harm caused by the use of whips, chains or training implements.[60]

Bolivia has enacted what animal rights activists called the world's first ban on all animals in circuses.[61]

Bullfighting

Bullfighting is criticized by animal rights or animal welfare activists, referring to it as a cruel or barbaric blood sport in which the bull suffers severe stress and a slow, torturous death.[62][63] A number of activist groups undertake anti-bullfighting actions in Spain and other countries. In Spanish, opposition to bullfighting is referred to as antitaurismo.

The Bulletpoint Bullfight warns that bullfighting is "not for the squeamish", advising spectators to "be prepared for blood". It details prolonged and profuse bleeding caused by horse-mounted lancers, the charging by the bull of a blindfolded, armored horse who is "sometimes doped up, and unaware of the proximity of the bull", the placing of barbed darts by banderilleros, followed by the matador's fatal sword thrust. It stresses that these procedures are a normal part of bullfighting and that death is rarely instantaneous. It further warns those attending bullfights to "be prepared to witness various failed attempts at killing the animal before it lies down."[64]

Toro embolado

The "Toro Jubilo" or Toro embolado in Soria, Medinaceli, Spain, is a festival associated with animal cruelty. During this festival, balls of pitch are attached to a bull's horns and set on fire. The bull is then released into the streets and can do nothing but run around in pain, often smashing into walls in an attempt to douse the fire. These fiery balls can burn for hours, and they burn the bull's horns, body, and eyes – all while spectators cheer and run around the victim. The animal rights group PACMA has described the fiesta as "a clear example of animal mistreatment".[65]

Rattlesnake round-ups

Rattlesnake round-ups, also known as rattlesnake rodeos, are annual events common in the rural Midwest and Southern United States, where the primary attractions are captured wild rattlesnakes which are sold, displayed, killed for food or animal products (such as snakeskin) or released back into the wild. The largest rattlesnake round-up in the United States is held in Sweetwater, Texas. Held every year since 1958, the event currently attracts approximately 30,000 visitors per year and in 2006 each annual round-up was said to result in the capture of 1% of the state's rattlesnake population.[66] Rattlesnake round-ups became a concern by animal welfare groups and conservationists due to claims of animal cruelty and excessive threat of future endangerment.[67][68][69] In response, some round-ups impose catch-size restrictions or releasing captured snakes back into the wild.[70][71]

Warfare

Military animals are creatures that have been employed by humankind for use in warfare. They are a specific application of working animals. Examples include horses, dogs and dolphins. Only recently has the involvement of animals in war been questioned, and practices such as using animals for fighting, as living bombs (as in the use of exploding donkeys) or for military testing purposes (such as during the Bikini atomic experiments) may now be criticised for being cruel.[72]

Princess Anne, the Princess Royal, the patron of the British Animals in War Memorial, stated that animals adapt to what humans want them to do, but that they will not do things that they do not want to, even with training.[73] Animal participation in human conflict was commemorated in the United Kingdom in 2004 with the erection of the Animals in War Memorial in Hyde Park, London.[74]

In 2008 a video of US Marine David Motari throwing a puppy over a cliff during the Iraq conflict was popularised as an internet phenomenon and attracted widespread criticism of the soldier's actions for being an act of cruelty.[75]

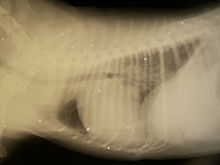

Unnecessary scientific experiments or demonstrations

| | Nationwide ban on all cosmetic testing on animals | | Partial ban on cosmetic testing on animals1 |

| | Ban on the sale of cosmetics tested on animals | | No ban on any cosmetic testing on animals |

| | Unknown |

Template:Legality of primate use in scientific research Under all three of the conceptual approaches to animal cruelty discussed above, performing unnecessary experiments or demonstrations upon animals that cause them substantial pain or distress may be viewed as cruelty. Due to changes in ethical standards, this type of cruelty tends to be less common today than it used to be in the past. For example, schoolroom demonstrations of oxygen depletion routinely suffocated birds by placing them under a glass cover,[76] and animals were suffocated in the Cave of Dogs[77][78][79] to demonstrate the density and toxicity of carbon dioxide to curious travellers on the Grand Tour.

No pet policies and abandonment

Many apartment complexes and rental homes institute no pet policies. No pet policies are a leading cause of animal abandonment, which is considered a crime in many jurisdictions. In many cases, abandoned pets have to be euthanized due to the strain they put on animal shelters and rescue groups. Abandoned animals often become feral or contribute to feral populations. In particular, feral dogs can pose a serious threat to pets, children, and livestock.[80]

In Ontario, Canada, no pet policies are outlawed under the Ontario Landlord and Tenant Act and are considered invalid even when a tenant signs a lease that includes a no pets clause.[81] Similar legislation has also been considered in Manitoba.[82]

Laws by country

Template:World laws on animal crueltyMany jurisdictions around the world have enacted statutes which forbid cruelty to some animals but these vary by country and in some cases by the use or practice.

Africa

Egypt

Egyptian law states that anyone who inhumanely beats or intentionally kills any domesticated animal may be jailed or fined.[83] The Egyptian Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was established by the British over a hundred years ago, and is currently administered by the Egyptians. The SPCA was instrumental in promoting a 1997 ban on bullfighting in Egypt.[84]

In ancient Egyptian law, the killers of cats or dogs were executed.[85][86]

South Africa

The Animal Protection Act No 71 of 1962 in South Africa covers "farm animals, domestic animals and birds, and wild animals, birds, and reptiles that are in captivity or under the control of humans."

The Act contains a detailed list of prohibited acts of cruelty including overloading, causing unnecessary suffering due to confinement, chaining or tethering, abandonment, unnecessarily denying food or water, keeping in a dirty or parasitic condition, or failing to provide veterinary assistance. There is also a general provision prohibiting wanton, unreasonable, or negligible commission or omission of acts resulting in unnecessary suffering. The Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries for 2013/14 to 2016/17 mentions updating animal protection legislation.[87]

The NSPCA is the largest and oldest animal welfare organisation in South Africa that enforces 90% of all animal cruelty cases in the country by means of enforcing the Animals Protection Act.

South Sudan

The Criminal Code of South Sudan has laws against maltreatment of animals. The laws read:[88]

196. Ill-treatment of Domestic Animal.

- Whoever cruelly beats, tortures or otherwise willfully ill-treats any tame, domestic or wild animal, which has previously been deprived of its liberty, or arranges, promotes or organizes fights between cocks, rams, bulls or other domestic animals or encourages such acts, commits an offence, and upon conviction, shall be sentenced to imprisonment for a term not exceeding two months or with a

197. Riding and Neglect of Animal.

- Whoever wantonly rides, overdrives or overloads any animal or intentionally drugs or employs any animal, which by reason of age, sickness, wounds or infirmity is not in a condition to work, or neglects any animal in such a manner as to cause it unnecessary suffering, commits an offence, and upon conviction, shall be sentenced to imprisonment for a term not exceeding one month or with a fine or with both.

Americas

Argentina

In Argentina, National Law 14346 sanctions with from 15 days to one year in prison those who mistreat or inflict acts of cruelty on animals.[89]

Brazil

Canada

In Canada, it is an offence under the Criminal Code to intentionally cause unnecessary pain, suffering or injury to an animal.[90] Poisoning animals is specifically prohibited.[90][91] It is also an offence to threaten to harm an animal belonging to someone else.[92] Most provinces and Territories also have their own animal protection legislation.[93] However, it is not explicitly illegal in Canadian law to kill a dog or cat for consumption.[94]

The Animal Legal Defense Fund releases an annual report ranking the animal protection laws of every province and territory based on their relative strength and general comprehensiveness. In 2014, the top four jurisdictions were Manitoba, British Columbia, Ontario and Nova Scotia. The worst four were Saskatchewan, Northwest Territories, Quebec, and Nunavut.[95]

Chile

Law 20380 established sanctions including fines, from 2 to 30 Mensual Tributary Units, and prison, from 541 days to 3 years, for those involved in acts of animal cruelty. Also, it promotes animal care through school education, and establishes a Bioethics Committee to define policies related to experiments with animals.[96]

Colombia

In Colombia, there is little control over cruel behaviors against animals, and the government has proposed that bullfighting be declared a "Cultural Heritage"; other cruel activities like cockfighting are given the same legal treatment.[97]

Costa Rica

In 2017, after many years of legal wrangling, Costa Rica passed their Animal Welfare Law. It includes prison sentences of 3 months to one year for harming or killing a domesticated animal or for conducting animal fights. There are monetary fines for those who mistreat, neglect or abandon animals, for breeding or training animals for fighting, or violating regulations on animal experimentation. The law doesn't cover agricultural practices, aquaculture, zootechnical or veterinary activities, killing of animals for consumption, for sanitary or scientific reasons, or for reproductive control. Wild animals are covered under the Wild Life Act.[98][99]

The bill had stalled its motion through the legislature until an injured toucan was found which had lost the top half of its beak. News and images of the injured bird, now named Grecia, raised enough contributions to create a 3D printed prosthesis for her, and helped spur the bill's progress.[100]

Mexico

The current policy of Mexico, in civil law, condemns physical harm to animals as property damage to the owners of the abused animal, considering the animals as owned property.

In criminal law, the situation is different. In December 2012, the Legislative Assembly of the Federal District reformed the existing Penal Code of Mexico City, establishing abuse and cruelty to animals as criminal offenses, provided the animals are not deemed to be plagues or pests. Abandoned animals are not considered to be plagues. A subsequent reform was entered into force on 31 January 2013, by a decree published in the Official Gazette of the Federal District. The law provides penalties of 6 months to 2 years imprisonment, and a fine of 50 to 100 days at minimum wage, to persons who cause obvious injury to an animal, and the penalty is increased by one half if those injuries endanger its life. The penalty rises to 2 to 4 years of prison, and a fine of 200 to 400 days at minimum wage, if the person intentionally causes the death of an animal.[101]

This law is considered to extend throughout the rest of the 31 constituent states of the country. In addition, The Law of Animal Protection of the Federal District is wide-ranging, based on banning "unnecessary suffering". Similar laws now exist in most states.[102]

United States

The primary federal law relating to animal care and conditions in the US is the Animal Welfare Act of 1966, amended in 1970, 1976, 1985, 1990, 2002 and 2007. It is the only Federal law in the United States that regulates the treatment of animals in research, exhibition, transport, and by dealers. Other laws, policies, and guidelines may include additional species coverage or specifications for animal care and use, but all refer to the Animal Welfare Act as the minimum acceptable standard.[103]

The Animal Legal Defense Fund releases an annual report ranking the animal protection laws of every state based on their relative strength and general comprehensiveness. In 2013's report, the top five states for their strong anti-cruelty laws were Illinois, Maine, Michigan, Oregon, and California. The five states with the weakest animal cruelty laws in 2013 were Kentucky, Iowa, South Dakota, New Mexico, and Wyoming.[104]

In Massachusetts and New York, agents of humane societies and associations may be appointed as special officers to enforce statutes outlawing animal cruelty.[105]

In 2004, a Florida legislator proposed a ban on "cruelty to bovines," stating: "A person who, for the purpose of practice, entertainment, or sport, intentionally fells, trips, or otherwise causes a cow to fall or lose its balance by means of roping, lassoing, dragging, or otherwise touching the tail of the cow commits a misdemeanor of the first degree."[106] The proposal did not become law.[106]

In the United States, ear cropping, tail docking, rodeo sports, and other acts are legal and sometimes condoned. Penalties for cruelty can be minimal, if pursued. Currently, 46 of the 50 states have enacted felony penalties for certain forms of animal abuse.[107] However, in most jurisdictions, animal cruelty is most commonly charged as a misdemeanor offense. In one recent California case, a felony conviction for animal cruelty could theoretically net a 25-year to life sentence due to their three-strikes law, which increases sentences based on prior felony convictions.[108]

In 2003, West Hollywood, California passed an ordinance banning declawing of house cats.[109] In 2007, Norfolk, Virginia passed legislation only allowing the procedure for medical reasons.[110] However, most jurisdictions allow the procedure.

In April 2013, Texas Federal Court Judge Sim Lake ruled[111] that the Animal Crush Video Prohibition Act of 2010, which criminalized the recording, sale, and transport of videos depicting animal cruelty as obscenity, is in violation of the First Amendment. Judge Lake noted that obscenity tests require an explicitly sexual depiction, which the criminalized videos lack. This follows the precedent set by United States v. Stevens, which additionally held that restrictions on the possession of animal cruelty videos were unconstitutional.

In November 2019, President Trump signed the Preventing Animal Cruelty and Torture Act, making certain intentional acts of cruelty to animals federal crimes carrying penalties of up to seven years in prison. The Act expanded upon the 2010 Animal Crush Video Prohibition Act signed by President Barack Obama that banned the creation and distribution of videos that showed animals being crushed, burned, drowned, suffocated, impaled or subjected to other forms of torture. The underlying acts, which were not included in the 2010 bill, are part of the PACT Act and are now felony offenses. The bill was unanimously passed in both the House and Senate.[112][113]

State welfare laws

Several states have enacted or considered laws in support of humane farming.

- On 5 November 2002, Florida voters passed Amendment 10 by a margin of 55% for, amending the Florida Constitution to ban the confinement of pregnant pigs in gestation crates.[114]

- On 14 January 2004, the bill AB-732 died in the California Assembly's Agriculture Committee.[115] The bill would have banned gestation and veal crates, eventually being amended to include only veal crates.[116] On 9 May 2007, the bill AB-594 was withdrawn from the California State Assembly. The bill had been effectively killed in the Assembly Agriculture Committee, by replacing the contents of the bill with language concerning tobacco cessation coverage under Medi-Cal.[117] AB-594 was very similar to the current language of Proposition 2.[118]

- On 7 November 2006, Arizona voters passed Proposition 204 with 62% support. The measure prohibits the confinement of calves in veal crates and breeding sows in gestation crates.[119]

- On 28 June 2007, Oregon Governor Ted Kulongoski signed a measure into law prohibiting the confinement of pigs in gestation crates (SB 694, 74th Leg. Assembly, Regular Session).[120]

- In January 2008, Nebraska State Senate bill LB 1148, to ban the use of gestation crates for pig farmers, was withdrawn within 5 days amidst controversy.[121]

- On 14 May 2008, Colorado Governor Bill Ritter signed into law a bill, SB 201, that phases out gestation crates and veal crates.[122][123]

Venezuela

Venezuela published a "Law for Protection of Domestic Fauna free and in captivity" in 2010, defining responsibilities and sanctions about animal care and ownership. Animal cruelty acts are fined, but are not a cause for imprisonment.[124] The law also forbids the possession, breeding and reproduction of pit bull dogs, among similar breeds that are alleged to be aggressive and dangerous. It elicited reactions from dog owners, who said that aggressiveness in dogs is determined more by treatment by the owner than by the breed itself.[125]

Asia

China

As of 2006 there were no laws in China governing acts of cruelty to animals.[126] There are no government supported charitable organizations like the RSPCA, which monitors the cases on animal cruelty. All kinds of animal abuses, such as to fish, tigers, and bears, are to be reported for law enforcement and animal welfare.[127][128][129][130][131][132]

In the absence of a unified law against animal mistreatment, the World Animal Protection notes that some legislation protecting the welfare of animals exists in certain contexts, especially ones used in research and in zoos.[133]

In September 2009, legislation was drafted to address deliberate cruelty to animals in China. If passed, the legislation would offer some protection to pets, captive wildlife and animals used in laboratories, as well as regulating how farm animals are raised, transported and slaughtered.[134]

In 2008, the People's Republic of China was in the process of making changes to its stray-dog population laws in the capital city, Beijing. Mr. Zheng Gang who is the director of the Internal and Judicial Committee which comes under the Beijing Municipal People's Congress (BMPC), supported the draft of the Beijing Municipal Regulation on Dogs from the local government. The law would replace the Beijing Municipal Regulation on Dog Ownership, introduced in 1989. The extant regulation talked of "strictly" limiting dog ownership and controlling the number of dogs in the city. The proposed draft focused instead on "strict management and combining restrictions with management."[135]

Hong Kong

As of 2010, Hong Kong has supplemented or replaced the laws against cruelty with a positive approach using laws that specify how animals should be treated.[136] The government department primarily responsible for animal welfare in Hong Kong is the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department (AFCD).

Laws enforced by the AFCD include these:

- the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Ordinance (also enforced by the police)

- the Public Health (Animals and Birds) Ordinance (including regulations for licences imposed on livestock keepers and animal traders and a Code of Standards for Licensed Animal Traders)

- the Dogs and Cats Ordinance

- the Pounds Ordinance

- the Rabies Ordinance

- the Wild Animals Protection Ordinance

In addition, the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (FEHD) does the following:

- enforces the Public Health and Municipal Services Ordinance, which includes regulations for slaughterhouses and wet markets

- publishes a Code of Practice for the Welfare of Food Animals (which describes their transport)

- publishes Operational Guidelines for the Welfare of Food Animals at Slaughterhouses

The Department of Health does the following:

- enforces the Animals (Control of Experiments) Ordinance.

- publishes a Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Experimental Purposes

As of 2006, Hong Kong has a law titled "Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Ordinance", with a maximum 3 year imprisonment and fines of HKD$200,000.[137]

India

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Contains 2012 information about a proposed act in 2011. Was it ever enacted?. (August 2020) |

The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960 was amended in the year 1982.[138] According to the newly amended Indian animal welfare act, 2011 cruelty to animals is an offence and is punishable with a fine which shall not be less than ten thousand Rupees, which may extend to twenty five thousand Rupees or with imprisonment up to two years or both in the case of a first offence. In the case of second or subsequent offence, with a fine which shall not be less than fifty thousand Rupees, but may extend to one lakh Rupees and with imprisonment with a term which shall not be less than one year but may extend to three years.[139] This amendment is currently awaiting ratification from the Government of India. The 1962 Act is the one that is practiced as of now. The maximum penalty under the 1962 Act is Rs. 50 (under $1).[140] Many organizations, including ones such as the local SPCA, PFA and Fosterdopt are actively involved in assisting the general population in reporting cruelty cases to the police and helping bring the perpetrator to justice. Due to this, much of change has been observed through the subcontinent.

Japan

In Japan, the 1973 Welfare and Management of Animals Act (amended in 1999 and 2005)[141] stipulates that "no person shall kill, injure, or inflict cruelty to animals without due course", and in particular, criminalises cruelty to all mammals, birds, and reptiles possessed by persons; as well as cattle, horses, goats, sheep, pigs, dogs, cats, pigeons, domestic rabbits, chickens, and domestic ducks regardless of whether they are in captivity.

- Killing or injuring without due reason: up to one year's imprisonment with labor or a fine of up to one million yen

- Cruelty such as causing debilitation by discontinuing feeding or watering without due reason: a fine of up to five hundred thousand yen

- Abandonment: a fine of up to five hundred thousand yen

Separate national and local ordinances exist with regards to ensuring health and safety of animals handled by pet shops and other businesses.

Animal experiments are regulated by the 2000 Law for the Humane Treatment and Management of Animals, which was amended in 2006.[142] This law requires those using animals to follow the principles outlined in the 3Rs and use as few animals as possible, and cause minimal distress and suffering. Regulation is at a local level based on national guidelines, but there are no governmental inspections of institutions and no reporting requirement for the numbers of animals used.[143]

Malaysia

Saudi Arabia

Veterinarian Lana Dunn and several Saudi nationals report that there are no laws to protect animals from cruelty since the term is not well-defined within the Saudi legal system. They point to a lack of a governing body to supervise conditions for animals, particularly in pet stores and in the exotic animal trade with East Africa.[144]

South Korea

South Korea's animal welfare laws are weak by international standards.[145]

Taiwan

The Taiwanese Animal Protection Act was passed in 1998, imposing fines up to NT$250,000 for cruelty. Criminal penalties for animal cruelty were enacted in 2007, including a maximum of 1 year imprisonment.[146]

Thailand

Thailand introduced its first animal welfare law in 2014. The Cruelty Prevention and Welfare of Animal Act, B.E. 2557 (2014) came into being on 27 December 2014.[147][148]

Europe

European Union

The European Union Council Directive 1999/74/EC[149] is a directive passed by the European Union on the minimum standards for keeping egg laying hens which effectively bans conventional battery cages. The directive, passed in 1999, banned conventional battery cages in the EU from 1 January 2012 after a 13-year phase-out.

It is also illegal in many parts of Europe to declaw a cat.[150]

France

In France, cruelty to animals is punishable by imprisonment of two years and a financial penalty (30,000 €).[151]

Germany

In Germany, killing animals or causing significant pain (or prolonged or repeated pain) to them is punishable by imprisonment of up to three years or a financial penalty.[152] If the animal is of foreign origin, the act may also be punishable as criminal damage.[153]

Italy

Acts of cruelty against animals can be punished with imprisonment, for a minimum of three months up to a maximum of three years, and with a fine ranging from a minimum of 3,000 Euros to a maximum of 160,000 Euros, as for the law n°189/2004.[154]

Ireland

The Animal Health and Welfare Act 2013[155] came into force in 2014, improving animal protection.[156] The maximum penalty is up to €250,000 and up to 5 years in prison. Sentences of up to 3 years have been imposed in several cases.[citation needed]

Portugal

Since 1 October 2014, violence against animals has been a crime in Portugal. Legislation published in the Diário da Républica on 29 August criminalizes the mistreatment of animals, and indicates that "those who, without reasonable cause, inflict pain, suffering, or any other hardship to a companion animal abuse" are to be subject to imprisonment of up to one year.[157] If such acts result in the "death of the animal", the "deprivation of an important organ or member", or "serious and permanent impairment of its capacity of locomotion", those responsible will be punished by imprisonment up to two years.[157]

As for pets, the new law provides that "whoever, having the duty to store, monitor or pet watch, abandons them, thereby putting in danger their food and the provision of care owed" faces up to six months imprisonment.[157]

Sweden

In Sweden cruelty to animals is punishable by financial penalty and prison for up to 2 years. The owner will lose the right to own animals and the animals will be removed from the owner.[158]

Switzerland

The Swiss animal protection laws are among the strictest in the world, comprehensively regulating the treatment of animals including the size of rabbit cages, and the amount of exercise that must be provided to dogs.[159]

In the canton of Zurich an animal lawyer, Antoine Goetschel, is employed by the canton government to represent the interests of animals in animal cruelty cases.[160]

Turkey

Under Turkey's Animal Protection Law No. 5199, cruelty to animals is considered a misdemeanor, punishable by a fine only, with no jail time or a black mark on one's criminal record.[161][162] HAYTAP, the Animal Rights Federation in Turkey, believes that the present law does not contain a strong enough punishment for animal abusers.[163]

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, cruelty to animals is a criminal offence for which one may be jailed for up to 6 months.[164]

On 18 August 1911, the House of Commons introduced the Protection of Animals Act 1911 (c.27) following lobbying by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA). The maximum punishment was 6 months of "hard labour" with a fine of 25 pounds.[165]

In the Metropolitan Police Act 1839 "fighting or baiting Lions, Bears, Badgers, Cocks, Dogs, or other Animals" was prohibited in London, with a penalty of up to one month imprisonment, with possible hard labour, or up to five pounds. The law laid numerous restrictions on how, when, and where animals could be driven, wagons unloaded, etc.. It also prohibited owners from letting mad dogs run loose and gave police the right to destroy any dog suspected of being rabid or any dog bitten by a suspected rabid dog. The same law prohibited the use of dogs for drawing carts.[166]

Up until then, dogs were used for delivering milk, bread, fish, meat, fruit, vegetables, animal food (the cat's-meat man), and other items for sale and for collecting refuse (the rag-and-bone man).[167][168] As Nigel Rothfels notes, the prohibition against dogs pulling carts in or near London caused most of the dogs to be killed by their owners[169] as they went from being contributors to the family income to unaffordable expenses. Cart dogs were replaced by people with handcarts.[170] About 150,000 dogs were killed or abandoned. Erica Fudge quotes Hilda Kean:[169]

At the heart of nineteenth-century animal welfare campaigns is the middle-class desire not to be able to see cruelty.

— Hilda Kean, Animal Rights, 1998[171]

The Protection of Animals Act 1911[172] extended the ban on draft dogs to the rest of the kingdom. As many as 600,000 dogs were killed or abandoned.

The Protection of Animals Act 1911 has since been largely superseded by the Animal Welfare Act 2006,[173] which also superseded and consolidated more than 20 other pieces of legislation, including the Protection of Animals Act 1934 and the Abandonment of Animals Act 1960. The Act introduced the new welfare offence, which means that animal owners have a positive duty of care, and outlaws neglecting to provide for their animals' basic needs, such as access to adequate nutrition and veterinary care.[174]

Under the Criminal Damage Act 1971, domestic animals can be classed as property that is capable of being "damaged or destroyed". A charge of criminal damage may be appropriate for the injury or death of an animal owned by someone other than the defendant, and prosecution under the Animal Welfare Act 2006 may also be appropriate.[175][176]

Oceania

Australia

In Australia, all states and territories have enacted legislation governing animal welfare. The legislation are:[177]

- Animal Welfare Act 1992 (ACT)[178][179]

- Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1979 (NSW)[180][181]

- Animal Welfare Act (NT)[182][183]

- Animal Care and Protection Act 2001 (Qld)[184][185]

- Animal Welfare Act 1985 (SA)[186][187]

- Animal Welfare Act 1993 (Tas)[188][189]

- Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1986 (Vic)[190][191]

- Animal Welfare Act 2002 (WA)[192][193]

Welfare laws have been criticized as not adequately protecting animals.[194] Whilst police maintain an overall jurisdiction in prosecution of criminal matters, in many states officers of the RSPCA and other animal welfare charities are accorded authority to investigate and prosecute animal cruelty offenses.

New Zealand

The Animal Welfare Act 1999 protects animals from maltreatment.[195]

See also

- Bear-baiting

- Crush fetish

- Goat throwing

- Cat-burning

- Pain in animals

- Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

- List of animal welfare organizations

References

- ^ a b Warburton, Nigel. Philosophy : the basics (5th ed.). Routledge. p. 71. ISBN 9780415693172.

- ^ "The life of Leonardo da Vinci by Giorgio Vasari". Yale University Library Digital Collections. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (30 November 2011). "Leonardo da Vinci unleashed: the animal rights activist within the artist". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ Midgley, Mary (24 May 1999). "Descartes' prisoners". The New Statesman. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015.

- ^ a b Cassuto, David N. (2007). "Bred Meat: The Cultural Foundation of the Factory Farm". Law and Contemporary Problems. 70 (1): 59–87.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1871). The Descent of Man. D. Appleton and Company. p. 34. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ Rader, Priscilla, "Virtue Ethics and Non-Human Animals: The Missing Link to the Animal Liberation Movement" (2012). Humanities Capstone Projects. Paper 13.

- ^ "An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation". ebooks.adelaide.edu.au. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ a b Norwood, FB; Lusk, JL (2010). "Direct versus indirect questioning: An application to the well-being of farm animals". Soc Indic Res. 96 (3): 551–565. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9492-z. S2CID 145217722.

- ^ "Pet-Abuse.Com – Animal Cruelty". Pet-abuse.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ^ Salt, H.S. (1899) The Logic of Vegetarianism: Essays and Dialogues. London.

- ^ a b c Matheny, Gaverick; Leahy, Cheryl (2007). "Farm-Animal Welfare, Legislation, and Trade". Law and Contemporary Problems. 70 (1): 325–358.

- ^ "Are Farm Animals Not Considered Animals?". The Huffington Post. 25 August 2014. Archived from the original on 27 August 2014.

- ^ "Video: Shocking undercover footage from an egg hatchery – Telegraph". Telegraph.co.uk. 1 September 2009. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018.

- ^ "Are we the cruellest we've ever been? The way we treat animals suggests we are". 19 October 2015. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ Fiber-Ostrow, Pamela, Lovell, Jarret S. (2016) behind a veil of secrecy: animal abuse, factory farms, and Ag-Gag legislation. Contemporary Justice Review [online]. 19(2), 230 – 249.

- ^ AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2013 Edition Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. avma.org

- ^ "Executive Board meets pressing needs". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- ^ Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epiz.,. Global Perspectives on Animal Welfare: Asia, the Far East, and Oceania (n.d.): n. pag. 24 February 2005. Web.

- ^ Richard A. Oppel, Jr. (6 April 2013). "Taping of Farm Cruelty Is Becoming the Crime". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 April 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ Schwartzkopf-Genswein, K. S.; Stookey, J. M.; Welford, R. (1 August 1997). "Behavior of cattle during hot-iron and freeze branding and the effects on subsequent handling ease". Journal of Animal Science. 75 (8): 2064–2072. doi:10.2527/1997.7582064x. ISSN 0021-8812. PMID 9263052. S2CID 18911989.

- ^ Coetzee, Hans (19 May 2013). Pain Management, An Issue of Veterinary Clinics: Food Animal Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1455773763. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ "Welfare Implications of Dehorning and Disbudding Cattle". www.avma.org. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Goode, Erica (25 January 2012). "Ear-Tagging Proposal May Mean Fewer Branded Cattle". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Grandin, Temple (21 July 2015). Improving Animal Welfare, 2 Edition: A Practical Approach. CABI. ISBN 9781780644677. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ "Restraint of Livestock". www.grandin.com. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Doyle, Rebecca; Moran, John (3 February 2015). Cow Talk: Understanding Dairy Cow Behaviour to Improve Their Welfare on Asian Farms. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 9781486301621. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ a b "The Issue". Stop Yulin Forever. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ Rogers, Martin. "Inside the grim scene of a Korean dog meat farm, just miles from the Winter Olympics". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ "Sheep dentistry, including tooth trimming". Australian Veterinary Association. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ Lockwood, Randall; Hodge, Guy R. (1986). "The tangled web of animal abuse: The links between cruelty to animals and human violence". Readings in Research and Applications: 77–82. Archived from the original on 23 June 2015.

- ^ Arluke, A.; Levin, J.; Luke, C.; Ascione, F. (1999). "The relationship of animal abuse to violence and other forms of antisocial behavior". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 14 (9): 963–975. doi:10.1177/088626099014009004. S2CID 145797691.

- ^ Alleyne, E., Tilston, L., Parfitt, C. and Butcher, R. (2015). "Adult-perpetrated animal abuse: development of a proclivity scale" (PDF). Psychology, Crime & Law. 21 (6): 570–588. doi:10.1080/1068316X.2014.999064. S2CID 143576557. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Baxendale, S., Lester, L., Johnston, R. and Cross, D. (2015). "Risk factors in adolescents' involvement in violent behaviours". Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research. 7 (1): 2–18. doi:10.1108/jacpr-09-2013-0025.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fitzgerald, Amy J.; Kalof, Linda; Dietz, Thomas (2009). "Slaughterhouses and Increased Crime Rates: An Empirical Analysis of the Spillover From "The Jungle" Into the Surrounding Community". Organization & Environment. 22 (2). Santa Barbara, California: SAGE Publications: 158–184. doi:10.1177/1350508416629456. S2CID 148368906. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ a b Felthous, Alan R. (1998). Aggression against Cats, Dogs, and People. In Cruelty to Animals and Interpersonal Violence: Readings in Research and Applications. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. pp. 159–167.

- ^ Goleman, Daniel (7 August 1991). "Clues to a Dark Nurturing Ground for One Serial Killer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 August 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ "Pet-Abuse.Com – Animal Cruelty". Pet-abuse.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ Gibson, Caitlin (24 September 2014). "Loudoun Program Underscores the Link between Domestic Violence, Animal Abuse". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016.

- ^ "Facts About Animal Abuse & Domestic Violence". American Humane Association. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- ^ "Domestic Violence & the Animal Abuse Link". Animaltherapy.net. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ^ Duncan, A.; et al. (2005). "Significance of Family Risk Factors in Development of Childhood Animal Cruelty in Adolescent Boys with Conduct Problems". Journal of Family Violence. 20 (4): 235–239. doi:10.1007/s10896-005-5987-9. S2CID 40008466.

- ^ "Animal Cruelty and Family Violence: Making the Connection". Humane Society of the United States. Archived from the original on 25 October 2008. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- ^ Hile, Jennifer (16 October 2002). "Activists Denounce Thailand's Elephant "Crushing" Ritual". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 18 February 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

Just before dawn in the remote highlands of northern Thailand, west of the village Mae Jaem, a four-year-old elephant bellows as seven village men stab nails into her ears and feet. She is tied up and immobilized in a small, wooden cage. Her cries are the only sounds to interrupt the otherwise quiet countryside. The cage is called a "training crush." It's the centerpiece of a centuries-old ritual in northern Thailand designed to domesticate young elephants. In addition to beatings, handlers use sleep-deprivation, hunger, and thirst to "break" the elephants' spirit and make them submissive to their owners.

- ^ Sherman, Mark (10 April 2010). "Court voids law aimed at animal cruelty videos". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ^ a b "Turner Classic Movies - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ "27 Jun 1982, Page 14 - The Pantagraph at Newspapers.com". Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2016.[subscription required]

- ^ "30 Sep 1980, Page 56 - St. Louis Post-Dispatch at Newspapers.com". Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ Andy McKeague, An Interview with Kim Ki-Duk and Suh Jung on The Isle Archived 28 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine at monstersandcritics.com, 11 May 2005. Retrieved 11 March 2006.

- ^ "Pointless Cannibal Holocaust Sequel in the Works". Fangoria. Archived from the original on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2007.

- ^ Times online, timesonline.co.uk Archived 19 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine 19 August 2007. Retrieved 25 August 2007.

- ^ Uproar at fish cruelty on YouTube. practicalfishkeeping.co.uk. 17 May 2007.

- ^ "Entertainment Industry FAQ". Archived from the original on 16 June 2008.

- ^ Movie Rating System. Earning Our Disclaimer. americanhumane.org

- ^ "Circus bans". Stop Circus Suffering. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ Pepper Tribute Archived 17 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Alsnowshead.tripod.com (3 September 1999). Retrieved on 14 December 2011.

- ^ The Wrestling Menu #25 – The History Of Al Snow. 4 December 2002

- ^ "Circus Incidents: Attacks, Abuse and Property Damage" (PDF). Humane Society of the United States. 1 June 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ "Circuses". Humane Society of the United States. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ^ Patton, K (1 April 2007). "Frequently Asked Questions: Do circus trainers/handlers abuse animals?". lionden.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 23 May 2008.

- ^ Bolivia bans all circus animals Archived 21 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Associated Press (via Guardian). 31 July 2009. Retrieved on 14 December 2011.

- ^ "What is bullfighting?". League Against Cruel Sports. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011.

- ^ "The suffering of bullfighting bulls". Archived from the original on 26 January 2009.

- ^ The Bulletpoint Bullfight, p. 6, ISBN 978-1-4116-7400-4

- ^ "Toro Jubilo fiesta returns to Medinaceli, Soria". Typically Spanish – Spain News. 29 October 2012. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 29 October 2012 suggested (help) - ^ "Texas Town Welcomes Rattlesnakes, Handlers". Associated Press. 11 March 2006. Archived from the original on 29 March 2006. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ^ Knight, Richard L.; Gutzwiller, Kevin J., eds. (1995). "Rattlesnake Round-ups". Wildlife and recreationists: coexistence through management and research. Island Press. pp. 313–322. ISBN 978-1-55963-257-7. Archived from the original on 23 August 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "American Society of Ichthyologists and herpetologists position paper on Rattlesnake roundups" (PDF). American Society of Ichthyologists and herpetologists. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 7 October 2008.

- ^ Rubio, Manny (1998). "Rattlesnake roundups". Rattlesnake: Portrait of a Predator. Smithsonian Books. ISBN 1-56098-808-8. Archived from the original on 23 August 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ "Noxen Rattlesnake Roundup". Noxen, Pa. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ "Environmentalists Tackle the Rattlesnake Rodeo". Associated Press. 21 April 2010. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ "Animals in War – The unseen casualties". Animal Aid. 1 June 2003. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ Price, Eluned (1 November 2004). "They served and suffered for us". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ "Animal war heroes statue unveiled". BBC News. 24 November 2004. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ Naughton, Philippe (4 March 2008). "Puppy-toss video makes Marine figure of hate". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- ^ Mangin, Arthur (23 August 1865). "L'air et le monde aérien". Tours, A. Mame et fils. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Taylor, An (1832). "Account of the Grotta del Cane; With Remarks Upon Suffocation by Carbonic Acid". The London Medical and Physical Journal: 278–285. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Fleming & Johnson, Toxic Airs: Body, Place, Planet in Historical Perspective, Pittsburgh, 255–256.

- ^ Kroonenberg, Why Hell Stinks of Sulfur: Mythology and Geology of the Underworld, Chicago, 2013, 41–45.

- ^ "U.S. Facing Feral-Dog Crisis". Archived from the original on 21 April 2014.

- ^ "Why no-pet rental clauses lack teeth". thestar.com. 7 December 2012. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017.

- ^ "No-pet policy for Man. renters could be outlawed". 15 February 2010. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014.

- ^ "Legislature Related to Animals in Egyptian Law" (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ^ Humanity, through animal care Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Weekly.ahram.org.eg (10 September 2003). Retrieved on 14 December 2011.

- ^ (Not-So-) BIZARRE DOG LAW California Man Faces Life in Prison for Killing Dog; and Tennessee Judge Slam-Dunks Puppy Mill Owners 14 July 2002 Dogs in the News Archived 19 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dennis C. Turner (26 June 2000). The domestic cat: the biology of its behaviour. Cambridge University Press. pp. 185–. ISBN 978-0-521-63648-3. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ "NSPCA Cares about all Animals". Nspca.co.za. Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ The Penal Code Act, 2008 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. sudantribune.com

- ^ "LEY 14346 – MALOS TRATOS Y ACTOS DE CRUELDAD A LOS ANIMALES" (PDF). Gobierno República de Argentina. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 December 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ a b "Cruelty to Animals" Archived 4 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Criminal Code, s. 445.1.

- ^ "Cattle and Other Animals" Archived 4 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Criminal Code, s. 445.

- ^ "Assaults" Archived 11 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Criminal Code, s. 264.1(1)(c).

- ^ "A Report on Animal Welfare Law in Canada" Archived 11 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Alberta Farm Animal Care, June 2004.

- ^ "Canine carcasses at Edmonton restaurant were coyotes - Canada - CBC News". 17 March 2016. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ "2014 Canadian Animal Protection Laws Rankings" Archived 10 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine, 5 June 2014, Animal Legal Defense Fund, report available for download at link.

- ^ "Ley 20380, SOBRE PROTECCIÓN DE ANIMALES" (PDF) (in Spanish). MINISTERIO DE SALUD; SUBSECRETARÍA DE SALUD PÚBLICA. October 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ "Colombian president offers to grant bullfighting status of cultural heritage". Retrieved 17 October 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Arias, L (12 June 2017). "President Solís signs new Animal Welfare Law". The Tico Times. Costa Rica. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ Arias, L (14 May 2017). "Lawmakers pass Animal Welfare Bill on first round vote". The Tico Times. Costa Rica. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ Khan, Carrie (27 August 2016). "After Losing Half A Beak, Grecia The Toucan Becomes A Symbol Against Abuse". NPR. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ "Finally, reform to the Penal Code of Mexico City on animal abuse". Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ "Lawmakers seek to position Federal enforcement of the Law of Animal Protection of the Federal District". Archived from the original on 22 July 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ "Legislative History of the Animal Welfare Act". Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ "Annual Study Names 2013's "Top Five States to be an Animal Abuser"". Animal Legal Defense Fund. Archived from the original on 22 July 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ Book Review: Brute Force: Animal Police and the Challenge of Cruelty Archived 28 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Ccja-acjp.ca. Retrieved on 14 December 2011.

- ^ a b Emery, David. "Florida to Consider Ban on Cow Tipping". About.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 7 June 2007.

- ^ "ALDF: U.S. Jurisdictions With and Without Felony Animal Cruelty Provisions". Aldf.org. Archived from the original on 29 June 2009. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

- ^ "Accused Dog Killer Could Get 25 Years to Life in Prison". Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ^ Judge allows California cities to ban cat declawing Archived 18 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Sfgate.com (11 October 2007). Retrieved on 14 December 2011.

- ^ "Norfolk Bans De-Clawing Of Cats". Archived from the original on 11 December 2008.

- ^ "'Animal crush' video charges dismissed in first case under new law". POLITICO. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013.

- ^ Zaveri, Mihir (25 November 2019). "President Trump Signs Federal Animal Cruelty Bill Into Law". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ Zarrell, Matt (25 November 2019). "President Trump signs animal cruelty bill into law, making it a federal felony". ABC News.

- ^ "PorkNet Newsletter". MetaFarms.com, Inc. 7 November 2002. Archived from the original on 14 March 2006. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- ^ "Criminal Justice and Judiciary". California State Senate. 2004. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011.

- ^ "AB-732 Analysis". California State Assembly. 14 January 2008. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010.

- ^ "2007 Mid Year Summary". California Assembly Committee on Agriculture. 2007. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010.

- ^ "AB-594 Analysis". California State Assembly. 9 May 2008. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008.

- ^ Andrea Johnson, "Polls Indicate Strong Support for Pen Gestation for Hogs" Archived 22 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine. 29 March 2007

- ^ "Back door activists gain momentum". Learfield Communications, Inc. 5 July 2007. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- ^ "Farm Animal Welfare Bill Killed in Legislature". Omaha World Daily. 17 February 2008.

- ^ "Farm Sanctuary Applauds Colorado for Passing Legislation Phasing out Veal and Gestation Crates". Reuters. 14 May 2008. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- ^ "Farm Animal Welfare Measure Becomes Law". Federation of Animal Science Societies (FASS). 14 May 2008. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- ^ Asamblea Nacional de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela. "LEY PARA LA PROTECCIÓN DE LA FAUNA DOMÉSTICA LIBRE Y EN CAUTIVERIO" (PDF). Diario El Universal. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ Joaquín Perez Guisado; Andre Muñoz Serrano (2009). "Factors Linked to Dominance Aggression in Dogs" (PDF). Journal of Animal and Veterinary Advances. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- ^ Richard Spencer. Just who is the glamorous kitten killer of Hangzhou? Archived 22 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine 3 April 2006.

- ^ SBS Australia. "The Biggest Chinese Restaurant in the World". Retrieved 4 November 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Journal of Ecotourism. "The Shark Watching Industry and its Potential Contribution to Shark Conservation". Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ Sohu Forum. "人類的飲食與野生動物的滅絕有著本質和必然的聯繫". Archived from the original on 23 March 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2008.

- ^ 中國青年報. "國家禁令擋不住虎骨酒熱銷". Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- ^ Jadecampus. "Conservationists Call on China to Support Law Over Tiger Farms". Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- ^ 中國青年報. "拿什麼拯救你可憐的黑熊:能不能不用熊膽?". Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- ^ "China". World Animal Protection. Archived from the original on 19 December 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "China unveils first ever animal cruelty legislation". The Daily Telegraph. London. 18 September 2009. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- ^ "Beijing loosens leash on pet dogs". Chinadaily.com.cn. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ^ Review of Animal Welfare Legislation in Hong Kong Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine by Amanda S. Whitfort and Fiona M. Woodhouse, June 2010. This document reviews animal welfare laws and compares them to those of Taiwan, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, the European Union, and the United States.

- ^ Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department, "Penalty for Cruelty to Animals Archived 23 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine," Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Chapter 169, Section 3) 15 December 2006

- ^ "The prevention of cruelty to animals act,1960" (PDF). Amendments. Ministry of environment and Forests, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ "Indian animal welfare act 2011" (PDF). Chapter IV.Cruelty to animals. Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ THE ANIMAL WELFARE ACT, 2011 Archived 4 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine. awbi.org

- ^ Act on Welfare and Management of Animals (Act No. 105 1 October 1973) Archived 26 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. (PDF). cas.go.jp (in Japanese and English). Retrieved on 14 December 2011.

- ^ Christopher S. Stevenson, Lisa A. Marshall and Douglas W. Morgan Japanese guidelines and regulations for scientific and ethical animal experimentation. Progress in Inflammation Research 2nd Edition 2006 p. 187. doi:10.1007/978-3-7643-7520-1_10

- ^ Select Committee on Animals In Scientific Procedures Archived 1 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine Report July 2002, Accessed 23 August 2007

- ^ Animal lovers lament lack of law against cruelty Archived 9 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Arabnews.com (12 March 2009). Retrieved on 14 December 2011.

- ^ World Animal Protection (2 November 2014). "Korea". Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ Koahsiung Municipal Institute for Animal Health, "Laws and Regulations[permanent dead link]," Animal Protection Act last amended 11 July 2007.[dead link]

- ^ "CRUELTY PREVENTION AND WELFARE OF ANIMAL ACT, B.E. 2557 (2014)". Thai SPCA. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ Kanchanalak, Pornpimol (13 November 2014). "A landmark victory for animal rights". The Nation. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ COUNCIL DIRECTIVE 1999/74/EC of 19 July 1999 Archived 7 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. European Union

- ^ Declawing Cats: Manicure or Mutilation?. dehumane.org

- ^ "Code pénal". legifrance.gouv.fr. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ § 17 Tierschutzgesetz (TierSchG) Archived 7 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Bundesrecht.juris.de. Retrieved on 14 December 2011.

- ^ § 303 Strafgesetzbuch (StGB) Archived 6 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Bundesrecht.juris.de. Retrieved on 14 December 2011.

- ^ The Italian Parliament – Law 189/2004 – Art. 544/ter/quater/quinquies Archived 8 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Camera.it. Retrieved on 14 December 2011. (in Italian)

- ^ "Animal Health and Welfare Act 2013". Archived from the original on 3 August 2014.

- ^ "New animal welfare legislation introduced". RTE.ie. 7 March 2014. Archived from the original on 25 October 2014.

- ^ a b c The Agency. "Boas Notícias – Animais: Lei que criminaliza maus-tratos entra em vigor". Archived from the original on 3 October 2014.

- ^ "Brottsbalk (1962:700)". Archived from the original on 12 April 2015.

- ^ Scales of Justice: In Zurich, Even Fish Have a Lawyer Archived 22 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Deborah Ball. The Wall Street Journal. 6 March 2010

- ^ The lawyer who defends animals Archived 22 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Leo Hickman. The Guardian. 5 March 2010

- ^ ANIMAL PROTECTION BILL LAW no 5199 Archived 25 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, HAYTAP, accessed 7 December 2012

- ^ "Civil society skeptical about amendment to animal protection law" Archived 2 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, HAYTAP, accessed 7 December 2012

- ^ "HAYTAP : Animal Rights Federation in Turkey" Archived 25 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, HAYTAP, accessed 7 December 2012

- ^ Animal Welfare Act 2006. Chapter 45 Archived 7 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine. (PDF). opsi.gov.uk. Retrieved on 14 December 2011.

- ^ The Times, Monday, 1 January 1912; p. 3; Issue 39783; col F "The Animals' New Magna Charter"

- ^ "London Police Act 1839, Great Britain Parliament. Section XXXI, XXXIV, XXXV, XLII". Archived from the original on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ /Graham Robb (2007). The discovery of France: a historical geography from the Revolution to the First World War. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 167–. ISBN 978-0-393-05973-1. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ Dog Carts and the Extinction of Memory Archived 8 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. 15 October 2008

- ^ a b Rothfels, Nigel, Representing Animals, Indiana University Press, p. 12, ISBN 978-0-253-34154-9. Chapter: 'A Left-handed Blow: Writing the History of Animals' by Erica Fudge

- ^ "igg.org.uk". Archived from the original on 31 July 2010.

- ^ Animal Rights by Hilda Kean, 1998, University of Chicago Press. Archived 11 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Protection of Animals Act 1911 Archived 13 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Animallaw.info (18 August 1911). Retrieved on 14 December 2011.

- ^ "Pet abuse law shake-up unveiled". BBC News Online. 14 October 2005. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- ^ "BBC – Ethics – Animal Ethics: Animal Welfare Act". BBC. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ "Cats And The Law – Cats Away". Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ "Offences involving Domestic and Captive Animals". The Crown Prosecution Service. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ^ "What is the Australian legislation governing animal welfare?". Archived from the original on 25 October 2014.

- ^ "ACT legislation register – Animal Welfare Act 1992 – main page". Archived from the original on 29 January 2016.

- ^ "ANIMAL WELFARE ACT 1992". Archived from the original on 25 January 2016.