Death and state funeral of Ruhollah Khomeini

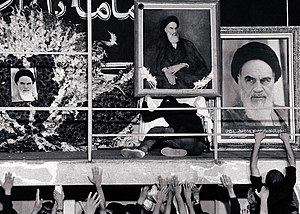

Mourning men in residency of Khomeini around his seat area, Jamaran. | |

| Date | 5–6 June 1989 |

|---|---|

| Location | Musalla, Tehran, Iran (Public viewing) Behesht-e Zahra cemetery (Burial) |

| Participants | Iranian officials and clerics, relatives and millions of followers. |

| Deaths | 8 due to a stampede |

On 3 June 1989, at 22:20 IRST, Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, leader of the Iranian Revolution and the first Supreme Leader and founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran, died in Jamaran, Greater Tehran aged 89 after spending eleven days at a private hospital, near his residency, after suffering five heart attacks in ten days.[1][2] Sources put his age at 89, and list the cause of death as bleeding in the digestive system.[3] As a mark of respect, Iran's government ordered all schools to be closed on Sunday and declared 40 days of mourning and said schools would be closed for five days.[4][5] Pakistan declared ten days of national mourning,[6] Syria announced seven days of mourning,[6] Afghanistan, Lebanon and India announced three days of mourning.[6][7]

Khomeini was given a state funeral and buried at the Behesht-e Zahra (The Paradise of Zahra) cemetery in south Tehran.[8] It was estimated that around 10 million people participated in his funeral, one-sixth of the population of Iran, which is the largest proportion of a population ever to attend a funeral procession and also one of the largest gatherings in human history.[9][10]

Funeral service[edit]

The first funeral[edit]

On 5 June, the coffin with Khomeini's body was transferred to the Musalla, a vacant lot in north Tehran. The body was displayed there on a high podium made out of steel shipping containers, in an air-conditioned glass case, wrapped in a white shroud. It stayed there until the next day allowing hundreds of thousands of mourners to see the body.[1] On 6 June, the body was brought down and the coffin opened for Grand Ayatollah Mohammad-Reza Golpaygani to lead the Salat al-Janazah (funeral prayer), which lasted for 20 minutes.[11] Afterwards, since the crowds of mourners had swelled overnight to several millions, it was impossible to deliver the body to the cemetery through Tehran to the southern part of the city in a procession. Eventually, the body was transferred to an Army Aviation Bell 214A/C helicopter and brought by air to the cemetery.[1] A stampede due to the massive crowd killed eight people at the funeral procession.[12]

At the cemetery, the crowd surged past the makeshift barriers and the authorities lost control of the events.[13] According to journalist John Kifner of The New York Times:

The crowd, much of it made up of Revolutionary Guards detailed to maintain order, pulled the coffin from the helicopter and began parading it around the makeshift compound surrounding the gravesite. As the excitement grew, the body of the Ayatollah, wrapped in a white burial shroud, fell out of the flimsy wooden coffin, and in a mad scene people in the crowd reached to touch the shroud. The soldiers pushed and wrestled, finally firing warning shots, to get the body back. Ayatollah Khomeini's son, Ahmad, was knocked from his feet. But even as the soldiers pushed the body back into the helicopter, the crowd swarmed over the craft, dragging it back down as it tried to take off. Others jumped into the hole dug for the Ayatollah's body. The troops drove the crowd back, finally clearing the compound enough to allow the helicopter to take off, its rotors scattering more mourners.[14]

The second funeral[edit]

The body was taken back to north Tehran to go through the ritual of preparation a second time. To thin the crowd, it was announced on television and radio that the funeral had been postponed. Five hours later, the body was returned to the cemetery and this time the guards were better prepared. The body was brought out of a helicopter, sealed in a metal box resembling an airline shipping container.[1] Once again, the crowd broke through the cordon, but by weight of numbers the guards managed to push their way through to the grave.[15] There, according to reporters for Time magazine:

The metal lid of the casket was ripped off, and the body was rolled into the grave. The grave was quickly covered with concrete slabs and a large freight container.[1]

In 1992, the construction of the Mausoleum of Ruhollah Khomeini on the burial site was completed.

See also[edit]

- Funeral of Qasem Soleimani

- Death and state funeral of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani

- 1989 Iranian Supreme Leader election

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Buchan, James (12 March 2009). "Ayatollah Khomeini's funeral: The funeral of Ayatollah Khomeini was not a tragedy but a gruesome farce". New Statesman. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ "Khomeini Had 5 Heart Attacks". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. 13 June 1989. Retrieved 12 November 2018 – via Google News.

- ^ "Khomeini, Imam of Iran And Foe of U.S., Is Dead". The New York Times. 4 June 1989. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ Moseley, Ray; Reaves, Joseph A. (June 7, 1989). "Mourners Rip Shroud, Khomeini's Body Falls". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ Joseph, Ralph (June 4, 1989). "Khomeini dead". UPI. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Death of the Ayatollah : Islamic Nations Mourning; Bhutto Hails Leadership". Los Angeles Times. 5 June 1989. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ Luddington, Nick (June 5, 1989). "Iraq, Isreal (sic) Call for Closer Ties with Iran; US Wants Hostages Freed with PM-Iran-Khomeini". Associated Press. Retrieved September 6, 2022.

- ^ Gölz, Olmo (2019-01-01). ""Die Drohung der ungewissen Zukunft: Der Tod Nassers und Khomeinis als Epochenbruch." In: Helden müssen sterben: Von Sinn und Fragwürdigkeit des heroischen Todes. Hg. von Cornelia Brink, Nicole Falkenhayner und Ralf von den Hoff, 231–45. Baden-Baden: Ergon, 2019" ["The Threat of an Uncertain Future: The Deaths of Nasser and Khomeini as an Epoch Break." In: Heroes must die: Of the meaning and dubiousness of heroic death. Edited by Cornelia Brink, Nicole Falkenhayner and Ralf von den Hoff, 231–45. Baden-Baden: Ergon, 2019.] (in German).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Pendle, George (2018-08-29). "Which Famous Figure Had the Biggest Public Funeral?". HISTORY. Archived from the original on 2021-10-30. Retrieved 2021-12-25.

- ^ Philipson, Alice (January 19, 2015). "The ten largest gatherings in human history". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2021.

- ^ Gölz, Olmo (2019-01-01). ""Die Drohung der ungewissen Zukunft: Der Tod Nassers und Khomeinis als Epochenbruch." In: Helden müssen sterben: Von Sinn und Fragwürdigkeit des heroischen Todes. Hg. von Cornelia Brink, Nicole Falkenhayner und Ralf von den Hoff, 231–45. Baden-Baden: Ergon, 2019" ["The Threat of an Uncertain Future: The Deaths of Nasser and Khomeini as an Epoch Break." In: Heroes must die: Of the meaning and dubiousness of heroic death. Edited by Cornelia Brink, Nicole Falkenhayner and Ralf von den Hoff, 231–45. Baden-Baden: Ergon, 2019.] (in German).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Iran TV: 35 killed in stampede at funeral for slain general - StarTribune.com". www.startribune.com. Archived from the original on 2020-01-07.

- ^ Pink/Gölz, "Die Drohung der ungewissen Zukunft: Der Tod Nassers und Khomeinis als Epochenbruch.", In: Helden müssen sterben: Von Sinn und Fragwürdigkeit des heroischen Todes. Hg. von Cornelia Brink, Nicole Falkenhayner and Ralf von den Hoff, 231–45. Baden-Baden: Ergon, 2019, p. 240-241.

- ^ Kifner, John (7 June 1989). "Amid Frenzy, Iranians Bury The Ayatollah". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 November 2018.

- ^ Gölz, Olmo (2019-01-01). ""Die Drohung der ungewissen Zukunft: Der Tod Nassers und Khomeinis als Epochenbruch." In: Helden müssen sterben: Von Sinn und Fragwürdigkeit des heroischen Todes. Hg. von Cornelia Brink, Nicole Falkenhayner und Ralf von den Hoff, 231–45. Baden-Baden: Ergon, 2019" ["The Threat of an Uncertain Future: The Deaths of Nasser and Khomeini as an Epoch Break." In: Heroes must die: Of the meaning and dubiousness of heroic death. Edited by Cornelia Brink, Nicole Falkenhayner and Ralf von den Hoff, 231–45. Baden-Baden: Ergon, 2019.] (in German).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)