Death of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

On 6 November 1893 [O.S. 25 October],[a 1] nine days after the premiere of his Sixth Symphony, the Pathétique, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky died in Saint Petersburg, at the age of 53. The official cause of death was reported to be cholera, most probably contracted through drinking contaminated water several days earlier. This explanation was accepted by many biographers of the composer. However, even at the time of Tchaikovsky's death, there were many questions about this diagnosis.[citation needed]

The timeline between Tchaikovsky's drinking unboiled water and the emergence of symptoms was brought into question, as well as the composer's procurement of unboiled water, in a reputable restaurant (according to one account), in the midst of a cholera epidemic with strict health regulations in effect. While cholera actually attacked all levels of Russian society, it was considered a disease of the lower classes. The resulting stigma from such a demise for a personage as famous as Tchaikovsky was considerable, to the point where its possibility was inconceivable for many people. The accuracy of the medical reports from the two physicians who had treated Tchaikovsky was questioned. The handling of Tchaikovsky's corpse was also scrutinised as it was reportedly not in accordance with official regulations for victims of cholera. This was remarked upon by, among others, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov in his autobiography, though some editions censored this section.[citation needed]

Theories that Tchaikovsky's death was a suicide soon began to surface. Postulations ranged from reckless action on the composer's part to orders from Tsar Alexander III of Russia, with the reporters ranging from Tchaikovsky's family members to composer Alexander Glazunov. Since 1979, one variation of the theory has gained some ground—a sentence of suicide imposed in a "court of honor" by Tchaikovsky's fellow alumni of the Imperial School of Jurisprudence, as a censure of the composer's homosexuality. Nonetheless, the cause of Tchaikovsky's death remains highly contested, and it may never actually be solved.

Final days[edit]

Biographer Alexander Poznansky writes that on 1 November 1893 [O.S. 20 October] (Wednesday) Tchaikovsky had gone to the theatre to see Alexander Ostrovsky's play The Ardent Heart. Afterwards, he went with his brother Modest, his nephew Vladimir "Bob" Davydov, the composer Alexander Glazunov, and other friends to a restaurant named Leiner's, located in Kotomin House at Nevsky Prospekt, Saint Petersburg. During the meal, Tchaikovsky ordered a glass of water. Due to an outbreak of cholera in the city, health regulations required water served in restaurants to be boiled before being served. Tchaikovsky was told by the waiter that no boiled water was then available. He then reportedly requested cold unboiled water, which was brought. Warned by others in his party not to drink it, the composer said he did not fear contracting cholera and drank the water anyway.[1]

The next morning, at Modest's apartment, Pyotr was not in the sitting room drinking tea as usual, but in bed complaining of diarrhea and an upset stomach. Modest asked about calling a doctor. Tchaikovsky refused, instead taking cod liver oil to no avail. Three days later, he developed signs of cholera. His condition worsened, but he still refused to see a doctor. A doctor was finally sent for but was not home, so another one was called. The diagnosis of cholera was finally made by Dr. Lev Bertenson. In the meantime, Tchaikovsky would seem to improve but then would regress and get much worse. His kidneys began to fail. A priest was called from St. Isaac's Cathedral to administer last rites, but the composer was too far gone to recognise what was going on around him. He died at 3 a.m. on 6 November 1893.[2]

After the death[edit]

Tchaikovsky biographer David Brown argues that, even before the doctors' accounts on the composer's death had appeared, what happened at his brother Modest's flat had been totally inconsistent with standard procedures for a death from cholera. Regulations stipulated the corpse was to be removed from the scene of death immediately in a closed coffin.[3] Instead, Tchaikovsky's body was displayed in Modest's flat, and the flat freely opened to visitors wishing to pay their last respects. Among the guests, composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov was seemingly bewildered by what he saw:[4] "How strange that, although death had resulted from cholera, still admission to the Mass for the dead was free to all! I remember how [Alexander] Verzhbilovich [a cellist and professor at the St. Petersburg Conservatory], totally drunk ... kept kissing the deceased man's head and face."[5] This passage was edited out of some later version of Rimsky-Korsakov's book.

Rimsky-Korsakov's own comments, however, would seem to conflict with his actions as later told by Sergei Diaghilev. Diaghilev, who would become known as the founder and impresario of the Ballets Russes, was at that time a university student in St. Petersburg and had met and occasionally conversed with the composer,[6] to whom he was distantly related by marriage.[7] On hearing of Tchaikovsky's death, Diaghilev recalls,

In despair I rushed out of the house, and although I realized Tchaikovsky had died of cholera I made straight for Malaya Morskaya, where he lived. The doors were wide open and there was no one to be found.... I heard voices from another room, and on entering I saw Pyotr Ilyich in a black morning coat stretched on a sofa. Rimsky-Korsakov and the singer Nikolay Figner were arranging a table to put him on. We lifted the body of Tchaikovsky, myself holding the feet, and laid it on the table. The three of us were alone in the flat, for after Tchaikovsky's death the whole household had fled....[8]

Poznansky counters Brown's views by saying that, despite Rimsky-Korsakov's comment, there was nothing odd about what went on. He writes that, despite lingering prejudice, the prevailing medical opinion was that cholera was less contagious than previously supposed. Though public gatherings for cholera victims had previously been discouraged, the Central Medical Council in the spring of 1893 specifically allowed public services and rituals in connection with the funerals of cholera victims.[9] Also, the medical opinion printed by the Petersburg Gazette stated that Tchaikovsky had died from a subsequent blood infection, not from the disease itself. (The disease had reportedly been arrested on Friday, 3 November, three days before the composer's passing.)[10] According to Poznansky, with the added precaution of constant disinfectant to the lips and nostrils of the body, even the drunken cellist kissing the face of the deceased had little cause for worry.[9]

Alexander III volunteered to pay the costs of the composer's funeral himself and instructed the Directorate of the Imperial Theatres to organise the event. According to Poznansky, this action showed the exceptional regard with which the Tsar regarded the composer. Only twice before had a Russian monarch shown such favor toward a fallen artistic or scholarly figure. Nicholas I had written a letter to the dying Alexander Pushkin following the poet's fatal duel. Nicholas also came personally to pay his final respects to historian Nikolay Karamzin on the eve of his burial.[11] Moreover, Alexander III gave special permission for Tchaikovsky's memorial service to be held at Kazan Cathedral.[12]

Tchaikovsky's funeral took place on 9 November 1893 in St. Petersburg. Kazan Cathedral holds 6,000 people, but 60,000 people applied for tickets to attend the service. Finally, 8,000 people were crammed in.[13] The composer was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, near the graves of fellow-composers Alexander Borodin, Mikhail Glinka and Modest Mussorgsky; eventually Rimsky-Korsakov and Mily Balakirev would be buried nearby, as well.[14]

Cholera in Russia[edit]

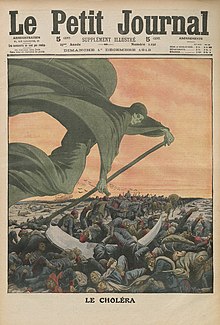

Biographer Anthony Holden writes that cholera had arrived in Europe less than a century before Tchaikovsky's death. An initial pandemic had hit the continent in 1818. Three others had followed and a fifth, which had begun in 1881, was raging.[15] The disease had been imported by pilgrims from Bombay to Arabia, and from there crossed the Russian border.[16]

The first reported cases in Russia from this pandemic occurred in Vladivostok in 1888. By 1892, Russia was by far the worst hit of the 21 countries affected. In 1893, no fewer than 70 regions and provinces were combatting epidemics.[16]

Holden adds that, according to contemporary Russian medical records, the specific epidemic which claimed Tchaikovsky's life began on 14 May 1892 and ended on 11 February 1896. During this time, 504,924 people contracted cholera. From that number, 226,940 (44.9 percent) died from it.[16]

A social stigma[edit]

Even with these numbers, the attribution of Tchaikovsky's death to cholera was as surprising to many as the suddenness of his demise. While cholera touched all levels of society, it was largely considered a disease of the poor. This stigma made cholera a vulgar and socially demeaning manner of demise. The fact Tchaikovsky died from such a cause appeared to degrade his reputation among the upper classes and struck many as inconceivable.[17]

True to its reputed form, the cholera outbreak that had begun in the summer of 1893 in St. Petersburg had been confined primarily to the city's slums, where the poor "lived in crowded, insanitary conditions without observing elementary medical conditions."[18] The disease did not affect more affluent and educated families because they observed the medical protocols forbidding the use or drinking of unboiled water.[18] Moreover, this epidemic had begun waning with the arrival of the cold autumn weather. On 13 October, 200 cases of cholera were reported. By 6 November, the day of Tchaikovsky's death, this number had been reduced to 68 cases, accompanied by "a sharp decline in mortality".[19] Though these figures were taken from Novosti i Birzhevaya Gazeta, Poznansky challenges them as inaccurate.[20]

Also, Tchaikovsky's friend Hermann Laroche reported that the composer was scrupulous in his personal hygiene.[21] In the hope of avoiding doctors, Laroche writes, "he relied above all on hygiene, of which he seemed (to my layman's view) to be a true master".[22] The media noted this as they questioned the composer's death. "How could Tchaikovsky, having just arrived in Petersburg and living in excellent hygienic conditions, have contracted the infection?" asked a reporter for the Petersburg Gazette.[23] A writer for Russian Life noted, "[E]veryone is astounded by the uncommon occurrence of the lightning-fast infection with Asiatic cholera of a man so very temperate, modest, and austere in his daily habits."[24]

Doctors not prepared[edit]

Holden maintains that, since cholera was rarely encountered in the upper echelons in which they practiced, it is possible that physicians Vasily and Lev Bertenson had never treated or even seen a case of cholera previous to the composer's case.[21] All they might have known of the disease was what they had read in textbooks and medical journals.[21] Poznansky cites Vasily Bertenson as later admitting that he "had not had occasion to witness an actual case of cholera", despite saying the composer had contracted a "classic case" of the disease.[25] Holden also questions whether Lev Bertenson's description of Tchaikovsky's condition came from his observation of the patient or from what he had once read. If the latter, it would mean he could have used the terminology in the wrong sequence in describing Tchaikovsky's diagnosis.[21]

The glass of unboiled water[edit]

If Tchaikovsky did contract cholera, it is unknown precisely when or how he became infected.[26] Newspapers printed accounts given by confused relatives of Tchaikovsky's drinking a glass of unboiled water at Leiner's restaurant. Modest, by contrast, suggests that his brother drank the fateful glass at Modest's apartment during lunch on Thursday.[26] If so, what was a pitcher of unboiled water doing on the table? "[I]t was right in the middle of our conversation about the medication he had taken that he poured a glass of water and took a sip from it. The water was unboiled. We were all frightened: he alone was indifferent to it and told us not to worry."[27]

The incubation period for cholera is between one and three days according to some authorities,[28] and from two hours to five days according to others.[29] Tchaikovsky reportedly started showing symptoms early Thursday morning. If the one-to-three-day interval is taken as 24 to 72 hours, the latest the composer could have been infected would have been Wednesday morning, earlier than either the dinner at Leiner's that evening or lunch at Modest's the following afternoon.[26]

The possibility of unboiled water available at a restaurant such as Leiner's was a surprise to some. "We find it extremely strange that a good restaurant could have served unboiled water during an epidemic", wrote a reporter for the newspaper Son of the Fatherland. "There exists, as far as we can recollect, a binding decree that commercial establishments, eating houses, restaurants, etc., should have boiled water".[30] Poznansky suggests the same lack of credibility holds true for Modest's story.[26] It was also well known that Tchaikovsky preferred to drink mineral water. "Are we to suppose that Leiner's had run out of both mineral and boiled water?"

Newspaper reporters were not the only ones questioning these accounts. Diaghilev recalls: "Various myths soon sprang up about the death of Tchaikovsky. Some said he caught cholera by drinking a glass of tap water at the Restaurant Leiner. Certainly, we used to see Pyotr Ilyich eating there almost every day, but nobody at that time drank unboiled water, and it seemed inconceivable to us that Tchaikovsky should have done so".[31]

Theories[edit]

Cholera from tainted water[edit]

Poznansky does not rule out Tchaikovsky's contracting cholera from drinking contaminated water. He ventures that Tchaikovsky could have possibly drunk it before the Wednesday supper at Leiner's, as the composer habitually drank cold water at meals.[32] On this point, he and Holden concur. Holden adds that Tchaikovsky may have even known he had contracted cholera before the dinner at Leiner's Wednesday night.[33]

Poznansky also says that the cholera bacillus was more prevalent in the St. Petersburg water supply than anyone had imagined before Tchaikovsky's death. Weeks after the composer's passing, both the Neva River and the water supply of the Winter Palace were found to be contaminated, and a special sanitary commission discovered that some restaurants mixed boiled and unboiled water to cool it more quickly for patrons.[34]

Another factor Pozansky mentions is that Tchaikovsky, already in gastric distress Thursday morning, drank a glass of the alkaline mineral water "Hunyadi János" in an attempt to ease his stomach. The alkaline in the mineral water would have neutralised the acid in Tchaikovsky's stomach. This would have stimulated any cholera bacillus present by giving it a more favorable environment in which to flourish.[32]

Cholera from other means[edit]

Referencing cholera specialist Dr. Valentin Pokovsky, Holden mentions another way Tchaikovsky could have contracted cholera—the "faecal-oral route", from less-than-hygienic sexual practices with male prostitutes in St. Petersburg.[35] This theory was advanced separately in The Times of London by its then veteran medical specialist, Dr. Thomas Stuttaford.[35] While Holden admits no further evidence supports this theory, he asserts that had it actually been the case, Tchaikovsky and Modest would have both gone to great pains to conceal the truth.[36] They could have staged Tchaikovsky's drinking unboiled water at Leiner's by mutual agreement for the sake of family, friends, admirers and posterity.[36] Since Tchaikovsky was an almost sacred national figure by this time in his life, Holden suggests the doctors involved with the composer's case might have gone along with this deception.[36]

Suicide ordered by "court of honor"[edit]

Another theory was first broached publicly by Russian musicologist Alexandra Orlova in 1979 when she emigrated to the West. The key witness for Orlova's account was Alexander Voitrov, a pupil at the School of Jurisprudence before World War I who had reportedly amassed much about the history and people of his alma mater. Among these people was Nikolay Borisovich Jacobi, Senior Procurator to the Senate in the 1890s. Jacobi's widow, Elizaveta Karlovna, reportedly told Voitrov in 1913 that a Duke Stenbok-Fermor was disturbed by the attention which Tchaikovsky was paying to his young nephew. Stenbok-Fernor wrote a letter of accusation to the Tsar in the autumn of 1893 and gave the letter to Jacobi to deliver. Jacobi wanted to avoid a public scandal. He therefore invited all of Tchaikovsky's former schoolmates that he could locate in St. Petersburg—eight people altogether—to serve in a "court of honor" to discuss the charge. This meeting, held in Jacobi's study, lasted almost five hours. At the end of that time, Tchaikovsky rushed out, pale and agitated, without saying a word. Once everyone else had left, Jacobi told his wife that they had decided that Tchaikovsky should kill himself. Within a day or two of this meeting, news of the composer's illness was circulating in St. Petersburg.[37]

Orlova suggests this court of honor could have been convened on 31 October. This is the only day during which nothing is known about Tchaikovsky's activities until evening. Brown suggests that perhaps it is significant that Modest records his brother's last days from that evening, when Tchaikovsky attended Anton Rubinstein's opera Die Maccabäer.[38]

In November 1993 the BBC aired a documentary entitled Pride or Prejudice, which investigated various theories regarding Tchaikovsky's death. Among those interviewed were Orlova, Brown and Poznansky, along with various experts on Russian history. Dr John Henry of Guy's Hospital, an expert witness working in the British National Poison Unit at the time, concluded in the documentary that all the reported symptoms of Tchaikovsky's illness "fit very closely with arsenic poisoning." He suggested that people would have known that acute diarrhoea, dehydration and kidney failure resembled the manifestations of cholera. This would help bolster a potential illusion of the death as a case of cholera. The conclusion reached in the documentary leaned largely in favor of the "court of honor" theory.[39]

Other well-respected studies of the composer have challenged Orlova's statements in detail and concluded that the composer's death was due to natural causes.[40] Among other challenges to Orlova's thesis, Poznansky revealed that there was no Duke Stenbok-Fermor, but there was a count of that name. However, he was an equerry to Tsar Alexander III and would not have needed an intermediary to deliver a letter to his own employer. As for the supposed threat to the reputation of the St Petersburg School of Jurisprudence represented by Tchaikovsky's homosexual affairs, Poznansky depicts the school as a hotbed of all-male debauchery which even had its own song hymning the delights of homosexuality.[41]

Suicide ordered by the Tsar[edit]

One other theory regarding Tchaikovsky's death is that it was ordered by Tsar Alexander III himself. This story was told by Swiss musicologist Robert-Aloys Mooser, who supposedly learned it from two others—Riccardo Drigo, composer and kapellmeister to the St. Petersburg Imperial Theatres, and the composer Alexander Glazunov. According to their scenario, the composer had seduced the son of the caretaker of his brother Modest's apartment block. The plausibility of this story for many people was that Glazunov reportedly confirmed it. Mooser considered Glazunov a reliable witness, stressing his "upright moral character, veneration for the composer and friendship with Tchaikovsky."[42] More recently the French scholar André Lischke has confirmed Glazunov's confession. Lischke's father was a student of the composer in Petrograd in the 1920s. Glazunov confided the story to Lischke's father, who in turn passed it to his son.[43]

However, Poznansky counters, Glazunov could not have confirmed the suicide story unless he were absolutely certain of its truth. The only way that could have been possible, though, was if he had been told by someone in Tchaikovsky's innermost circle—in other words, someone who was present at the composer's deathbed. It was exactly this circle of intimates, however, that Drigo accused of concealing the "truth", [Poznansky's quotation marks for emphasis] demanding false testimonies from authorities, physicians and priests. Only by swearing Glazunov to the strictest secrecy would anyone in this circle have revealed the "truth". That Glazunov would then share this information with Mooser, Poznansky concludes, is virtually inconceivable since it would have compromised Glazunov entirely.[44]

Suicide by reckless action[edit]

Another version holds that Tchaikovsky had been undergoing a severe personal crisis. This crisis was precipitated, according to some accounts, by his infatuation for his nephew, Vladimir Davydov, who was frequently referred to by the nickname "Bob" by the Davydov family and the composer.[45] This would reportedly explain the agonies expressed in the Sixth Symphony, as well as the mystery surrounding its program. Many analysts, working from this tangent, have since read the Pathétique as intensely autobiographical.[43] According to this theory, Tchaikovsky realised the full extent of his feelings for Bob, plus the unlikelihood of their physical fulfillment. He supposedly poured his misery onto this one last great work as a conscious prelude to suicide, then drank unboiled water in the hope of contracting cholera. In this way, as with his wading into the Moscow river in 1877 in frustration over his marriage, Tchaikovsky could commit suicide without bringing disgrace upon his family.[46]

No strong evidence[edit]

Without strong evidence for any of these cases, it is possible that no definite conclusion may be drawn and that the true nature of the composer's end may never be known.[41] Conclusive evidence, Holden suggests, would mean exhuming Tchaikovsky's corpse for tests to determine the presence of arsenic, as has been done with the body of Napoleon Bonaparte, since arsenic can remain in the human body even after 100 years.[47] Musicologist Roland John Wiley writes, "The polemics over [Tchaikovsky's] death have reached an impasse ... Rumor attached to the famous die hard ... As for illness, problems of evidence offer little hope of satisfactory resolution: the state of diagnosis; the confusion of witnesses; disregard of long-term effects of smoking and alcohol. We do not know how Tchaikovsky died. We may never find out...."[48]

Depictions in media[edit]

In the early 1980s, Canadian composer Claude Vivier had begun working on an opera entitled Tchaïkovski, un réquiem Russe (lit. Tchaikovsky, a Russian Requiem), which would have advanced the theory of suicide at the orders of Alexander III. Vivier announced the project to UNESCO music organizations and had begun writing a libretto, but he was murdered in a 1983 homophobic hate crime before the opera could be completed.[49]

English composer Michael Finnissy composed a short opera, Shameful Vice (1995), about Tchaikovsky's last days and death.[50][51]

Pathétique as Requiem[edit]

Volkov writes that even before Tchaikovsky's death, his Symphony No. 6 Pathetique, was heard by at least some as the composer's artistic farewell to this world. After the last rehearsal of the symphony under its composer's baton, Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, a talented poet and fervent admirer of the composer, ran into the greenroom weeping and exclaiming, "What have you done, it's a requiem, a requiem!"[52]

As for the première itself, Volkov writes:

Tchaikovsky began conducting with the baton held tightly in his fist ... in his usual manner. But when the final sounds of the symphony had died away and Tchaikovsky slowly lowered the baton, there was dead silence in the audience. Instead of applause, stifled sobs came from various parts of the hall. The audience was stunned and Tchaikovsky stood there, motionless, his head bowed.[53]

This would seem to contradict descriptions of this event by other biographers. Holden, for example, writes that the work had been greeted with respectful applause for its composer but general bewilderment about the work itself.[54] However, Diaghilev apparently confirms Volkov's account. Though he mentions "At the rehearsal opinions were greatly divided....", he adds: "The concert's success was naturally overwhelming."[8]

Regardless of its initial reception, two weeks after Tchaikovsky's death, on 18 November 1893, the composer's longtime friend, conductor Eduard Nápravník, led the second performance of the Pathétique Symphony at a memorial concert in St. Petersburg. This was three weeks to the day after the composer had led the première in the same hall, before much the same audience.

"It is indeed a sort of swan song, a presentiment of impending death, and hence its tragic impression" wrote the reviewer for the Russkaya Muzykal'naya Gazeta.[55] Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, who attended both performances, attributed the public's change in opinion to "the composer's sudden death ... stories about his presentiments of approaching demise (to which mankind is so prone), and a tendency to link these presentiments with the gloomy mood of the last movement of this splendid ... famed, even fashionable work."[56] Diaghilev adds that Nápravník wept throughout the performance.[8]

Though some modern musicologists, such as David Brown, dispute the view that Tchaikovsky wrote the Pathétique as his own requiem, many others, notably Milton Cross, David Ewen and Michael Paul Smith, accord it credence. The musical clues include one in the development section of the first movement, where the rapidly progressing evolution of the transformed first theme suddenly "shifts into neutral" in the strings, and a rather quiet, harmonised chorale emerges in the trombones. The trombone theme bears no relation to the music that either precedes or follows it. It appears to be a musical "non sequitur"—but it is from the Russian Orthodox Mass for the Dead, in which it is sung to the words: "And may his soul rest with the souls of all the saints."[citation needed]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Russia was still using old style dates in the 19th century, and information sources used in the article sometimes report dates as old style rather than new style. Dates in the article are taken verbatim from the source and therefore are in the same style as the source from which they come.

References[edit]

- ^ Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 579.

- ^ Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 579–589.

- ^ Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 1885–1893 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991), 481.

- ^ Brown, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 481.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, My Musical Life, 340.

- ^ Diaghilev, Sergei, Memoirs (unpublished). As quoted in Buckle, Richard, Diaghilev (New York: Athenum, 1979), 17–18.

- ^ Diaghilev's step-mother's sister, the soprano Aleksandra Panayeva-Kartsova, married Georgy Kartsov, the son of Tchaikovsky's first cousin Aleksandra Petrovna Kartsova née Tchaikovskaya.

- ^ a b c As quoted in Buckle, 23.

- ^ a b Poznansky, 592.

- ^ Petersburgaia gazeta, 26 October [6 November] 1893. As quoted in Poznansky, 592.

- ^ Poznansky, 594

- ^ Volkov, Solomon, St. Petersburg: A Cultural History (New York: The Free Press, 1995), 128.

- ^ Brown, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 486.

- ^ Brown, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 487.

- ^ See cholera: History: Origin and spread.

- ^ a b c "Asiatic Cholera", Encyclopedia of Brogkauz & Efron (St. Petersburg, 1903), vol. 37a, 507–151. As quoted in Holden, 359.

- ^ Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 596–597.

- ^ a b Orlova, Alexandra, "Tchaikovsky: The Last Chapter", 128. As quoted in Holden, Anthony, Tchaikovsky: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1995), 387.

- ^ Orlova, 128, footnote 12. As quoted in Holden, 387.

- ^ Poznansky, Tchaikovsky's Suicide: Myth and Reality, 217, note 81. As quoted in Holden, 474, footnote 36.

- ^ a b c d Holden, 360.

- ^ As quoted in Holden, 360.

- ^ Peterburgskaia gazeta, 7 November 1893, as quoted in Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 597.

- ^ Russkaia zhizn, 9 November 1893. As quoted in Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 597.

- ^ As cited in Poznansky, 581.

- ^ a b c d Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 582.

- ^ As quoted in Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 582.

- ^ ed. Berkow, Robert, The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, 15th ed. (New York, 1987); Entsiklopedicheskii slovar, s.v. "kholera." As quoted in Poznansky, 582.

- ^ WHO Fact Sheet: Cholera

- ^ Syn otechestva, 9 November 1893. As quoted in Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 597.

- ^ As quoted in Buckle, Richard, Diaghilev (New York: Athenum, 1979), 24.

- ^ a b Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 583.

- ^ Holden, 391.

- ^ Tolstoi, L., Polnoe sobranie sochinenli, 84:200–201. As quoted in Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 583.

- ^ a b Holden, 390

- ^ a b c Holden, 391

- ^ Brown, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 483–484; Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music (New York: Pegasus Books, 2007), 434–435.

- ^ Brown, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 484.

- ^ As cited in Norton, Rictor, "Gay Love-Letters from Tchaikovsky to his Nephew Bob Davidof", The Great Queens of History, 19 October 2002, updated 5 November 2005 <http://rictornorton.co.uk/tchaikov.htm>. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- ^ See, e.g., Tchaikovsky's Last Days by Alexander Poznansky.

- ^ a b The Daily Telegraph: "How did Tchaikovsky die?". Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- ^ As quoted in Holden, 374.

- ^ a b Holden, 374.

- ^ Poznansky, Tchaikovsky: The Story of the Inner Man, 606.

- ^ Polyansky, Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man, 333.

- ^ Holden, 374–375.

- ^ Henry, Dr. John, "Pride or Prejudice?" BBC Radio 3, 5 November 1993. As quoted in Holden, 399.

- ^ Wiley, New Grove (2001), 25:169.

- ^ Rhéaume, Martine (2021). "'I No Longer Feel Sorry for the Fact': Homosexuality and Identity Commitment in the Writings and Speeches of Claude Vivier". Circut. 31 (1). Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal: 27–41. doi:10.7202/1076403ar. S2CID 236686971.

- ^ "Opening Night! Opera & Oratorio Premieres". Stanford Universities Libraries. March 29, 1995. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ Williams, Nicholas (March 30, 1995). "Music: A few well-rounded suicide notes". Independent. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ Volkov, 115.

- ^ Volkov, Solomon, St. Petersburg: A Cultural History (New York: The Free Press, 1995), 115.

- ^ Holden, 371

- ^ As quoted in Holden, 371

- ^ Brown, David, Tchaikovsky Remembered (London: Faber & Faber, 1993) xv

Sources[edit]

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 1885–1893 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991).

- Brown, David, The Man and His Music (New York: Pegasus Books, 2007).

- Buckle, Richard, Diaghilev (New York: Athenum, 1979).

- Holden, Anthony, Tchaikovsky: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1995).

- Norton, Rictor, "Gay Love-Letters from Tchaikovsky to his Nephew Bob Davidof", The Great Queens of History, 19 October 2002, updated 5 November 2005 <http://rictornorton.co.uk/tchaikov.htm>.

- Poznansky, Alexander Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man (New York: Schirmer Books, 1991)

- Poznansky, Alexander, Tchaikovsky's Last Days.

- Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolai, Letopis Moyey Muzykalnoy Zhizni (St. Petersburg, 1909), published in English as My Musical Life (New York: Knopf, 1925, 3rd ed. 1942).

- Volkov, Solomon, St. Petersburg: A Cultural History (New York: The Free Press, 1995).

External links[edit]

- 6th symphony: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project – The passage discussed in last paragraph of the "Pathetique as a Requiem" section can be found shortly after rehearsal mark "K" in the score, or at 10:25 in the audio recording.