Deinacrida parva

| Deinacrida parva | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Orthoptera |

| Suborder: | Ensifera |

| Family: | Anostostomatidae |

| Genus: | Deinacrida |

| Species: | D. parva

|

| Binomial name | |

| Deinacrida parva Buller, 1895

| |

Deinacrida parva is a species of insect in the family Anostostomatidae, the king crickets and weta. It is known commonly as the Kaikoura wētā[1] or Kaikoura giant wētā.[2] It was first described in 1894 from a male individual[3] then rediscovered in 1966 by Dr J.C. Watt at Lake Sedgemore in Upper Wairau.[4] It is endemic to New Zealand, where it can be found in the northern half of the South Island.[2]

This is a small to medium-sized robust wētā.[5] It is easily confused with Deinacrida rugosa.[2][6][7] Due to the rarity of this weta, there is still much to be learnt.[8]

Description[edit]

Deinacrida parva have a rounded brown body.[9] The females are larger than the males in this species of wētā, but the males have long legs suggesting scramble competition for mates.[10][11] The females have a large spike on the end of their body, this spike is called an ovipositor and is used for laying eggs.[12]

The Kaikoura giant wētā can grow up to around 100mm in size[12] and weigh up to 14.5 grams.[13] They have a life span of roughly two years.[4] This wētā, although very similar in appearance, is smaller in size than D. rugosa and is a brown colour[10] with darker colouring under the abdomen.[9] Red or pink coloration can also be present on the border of the thoracic shield.[2] A major identification of the Kaikoura Wētā is by counting the six spines present on the lower hind leg.[2]

The taxonomic status of D.parva and D. rugosa were investigated.[2] These two are species are morphologically similar and phylogenetically sister species.[14]

Habitat and distribution[edit]

Deinacrida parva are found in many different terrestrial environments[15] but most commonly under large logs on river flats and scrub areas close to the edges of the forests.[2] Large proportions of individuals are found under Mataī logs.[8] Their preference for living close to water ways has resulted in the drowning of some individuals, although this might be linked to infection by internal parasites.[13]

D. parva are found between 150 and 1500m above sea level from South Marlborough to Hanmer Springs.[2] These weta are considered subalpine specialists.[16] They are most common surrounding Hapuku and Kowhai river close to Kaikōura (hence the name of these wētā).[2]

It is suspected they now occupy less than 10% of their former range.[17]

Diet[edit]

Deinacrida parva are herbivorous and feed mainly on the leaves of trees and shrubs.[18] Females of this species have been known to eat carcasses of dead or dying insects for extra protein during breeding season for egg development.[8]

Behaviour[edit]

This weta, like many of the other weta in New Zealand, is nocturnal.[19]

D. parva are able to produce sounds by rubbing tergite spines and hair sensilla together (located on their abdominal plates).[5] The sounds are normally produced during contraction of the abdomen and often in time with a defensive leg kick as a warning.[5] This is called the tergo-tergal mechanism.[5] The sounds produced are a soft hiss and often fall within ultrasonic frequencies.[5]

Using hair sensilla for sound production is a rare occurrence in arthropods and a potential explanation for why it has occurred in this species is that it has evolved under predation pressure by the endemic short-tailed bat in New Zealand.[5] There are no current evidence that the sounds produced are for intraspecific communication but it has not been researched extensively.[5]

Breeding[edit]

D. parva have been breed in captivity.[2] But due to wētā being captured at different ages and conditions, breeding pairs were hard to establish.[4] Young wētā come to sexual maturity successfully in captivity but some fail to lay eggs.[8] Females lay eggs in the soil with an ovipositor.[12]

Conservation[edit]

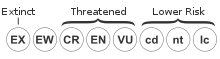

Populations in some parts have declined to a few individuals.[2] Many of the die-offs have been in the large populations close to Kaikoura.[2] Even though there has been a die off the population is considered to be stable.[17]

A major reason for decline is likely due to habitat clearance and predation by pests.[2] The changes in the natural habitat of D. parva has affected the chances of future survival in many of the smaller recorded populations.[2] Many of their original habitats have been cleared for pasture.[4] The die-offs could be associated with the Gordian worm parasite.[2] But the full impact of the parasite is unknown and still requires further research.[8] D. parva that become hosts for the Gordian worm parasite have been shown to have lowered reproductive capabilities.[8]

Further population surveys and full distribution research needs to be conducted for further information.[8] Although that has been difficult due to low population numbers, thick vegetation and uneven grounds.[8] Searching for these weta in the fallen logs (where they are most likely to be found) also damages and degrades the logs quicker and leaves less available habitats for them.[4] It has been proposed that they should be bred and then released on predator-free islands.[8] Mainland habitat management has also been suggested as a conservation plan.[4]

References[edit]

- ^ a b World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1996). "Deinacrida parva". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T6308A12602589. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T6308A12602589.en. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Threatened Weta Recovery Plan. New Zealand Department of Conservation. December 1998.

- ^ Ramsay, G. W. (1971). "Rediscovery of Sir Walter Buller's Weta,Deinacrida Parva(Orthoptera : Gryllacridoidea : Henicidae)". New Zealand Entomologist. 5 (1): 52–53. doi:10.1080/00779962.1971.9722956. ISSN 0077-9962.

- ^ a b c d e f Meads, M.J. (1987). The giant weta (Deinacrida parva) at Puhi Puhi, Kaikoura: present status and strategy for saving the species. Lower Hutt, NZ: Ecology Division, DSIR.

- ^ a b c d e f g Field, Laurence H; Roberts, Kelly L (2003). "Novel use of hair sensilla in acoustic stridulation by New Zealand giant wetas (Orthoptera: Anostostomatidae)". Arthropod Structure & Development. 31 (4): 287–296. doi:10.1016/S1467-8039(03)00005-7. PMID 18088987.

- ^ Trewick, Steven A.; Morgan-Richards, Mary (2004). "Phylogenetics of New Zealand's tree, giant and tusked weta (Orthoptera: Anostostomatidae): evidence from mitochondrial DNA". Journal of Orthoptera Research. 13 (2): 185–196. doi:10.1665/1082-6467(2004)013[0185:ponztg]2.0.co;2. ISSN 1082-6467.

- ^ Morgan-Richards, Mary; Gibbs, George W. (2001). "A phylogenetic analysis of New Zealand giant and tree weta (Orthoptera : Anostostomatidae : Deinacrida and Hemideina) using morphological and genetic characters". Invertebrate Systematics. 15 (1): 1. doi:10.1071/it99022. ISSN 1445-5226.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Meads, Michael John (1989). An evaluation of the conservation status of the giant weta (Deinacrida parva) at Kaikoura. Lower Hutt, NZ: Ecology Division, DSIR.

- ^ a b "Deinacrida parva. sp. nov | NZETC". nzetc.victoria.ac.nz. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- ^ a b Gibbs, G. W. (1999). "Four new species of giant weta, Deinacrida (Orthoptera: Anostostomatidae: Deinacridinae) from New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 29 (4): 307–324. doi:10.1080/03014223.1999.9517600. ISSN 0303-6758.

- ^ Kelly, Clint D.; Bussière, Luc F.; Gwynne, Darryl T. (2008-09-01). "Sexual Selection for Male Mobility in a Giant Insect with Female‐Biased Size Dimorphism". The American Naturalist. 172 (3): 417–423. doi:10.1086/589894. hdl:1893/914. ISSN 0003-0147. PMID 18651830. S2CID 22494505.

- ^ a b c "Hitchhiking giant wētā". Otago Museum. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- ^ a b The biology of wetas, king crickets and their allies. Field, L. H. (Laurence H.). Wallingford, Oxon., UK: CABI Pub. 2001. ISBN 978-0-85199-408-6. OCLC 559432458.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Twort, Victoria G; Newcomb, Richard D; Buckley, Thomas R (2019-04-01). Bryant, David (ed.). "New Zealand Tree and Giant Wētā (Orthoptera) Transcriptomics Reveal Divergent Selection Patterns in Metabolic Loci". Genome Biology and Evolution. 11 (4): 1293–1306. doi:10.1093/gbe/evz070. ISSN 1759-6653. PMC 6486805. PMID 30957857.

- ^ Trewick, Steven A.; Morgan-Richards, Mary (2005). "After the Deluge: Mitochondrial DNA Indicates Miocene Radiation and Pliocene Adaptation of Tree and Giant Weta (Orthoptera: Anostostomatidae)". Journal of Biogeography. 32 (2): 295–309. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2004.01179.x. ISSN 0305-0270. JSTOR 3566411.

- ^ "Northern part of New Zealand's South Island | Ecoregions | WWF". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- ^ a b "NZTCS". nztcs.org.nz. Retrieved 2020-07-05.

- ^ Trewick, Steven A.; Morgan-Richards, Mary (2004). "Phylogenetics of New Zealand's Tree, Giant and Tusked Weta (Orthoptera: Anostostomatidae): Evidence from Mitochondrial DNA". Journal of Orthoptera Research. 13 (2): 185–196. doi:10.1665/1082-6467(2004)013[0185:PONZTG]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1082-6467. JSTOR 3503721.

- ^ "TerraNature | New Zealand Ecology - weta". www.terranature.org. Retrieved 2020-07-03.