Dick-a-Dick

Dick-a-Dick (traditional name Lavanya, Jumgumjenanuke or Jungunjinuke,[1] c. 1834 – 3 September 1870) was an Australian Aboriginal tracker and cricketer, a Wotjobaluk man who spoke the Wergaia language in the Wimmera region of western Victoria, Australia. He was a member of the first Australian cricket team to tour England in 1868[2] and was one of the most well-known Aborigines of the nineteenth century.

Early life[edit]

Dick-a-Dick was born in the area around what is now Nhill, Victoria, the eldest son of Wotjobaluk Chief Balrootan.[3] He later claimed that, aged about ten, he was present at the European discovery of Nhill by explorers Dugald MacPherson and George Belcher in 1844.[3]

Aboriginal tracker[edit]

Living at Mt Elgin station in the Wimmera,[3] Dick-a-Dick first gained notability as a talented tracker, someone who could read the land well enough to find and follow the tracks of people or animals. On Friday, 12 August 1864, three white children, Isaac Cooper, Jane Cooper and Frank Duff, went missing in the Mallee scrub of the Wimmera near Natimuk on the edge of the Little Desert; and, although their tracks were found the following day, a thunderstorm erupted soon after and destroyed the tracks.[1]

The official search was cancelled soon after the storm and newspapers reported the children as dead. On Thursday, 18 August, a neighbour of the Duff's suggested asking Dick-a-Dick and other Wotjobaluk trackers for assistance; the parents, who had not given up hope of finding their children, readily agreed.[1] Dick-a-Dick took two other Wotjobaluk men, Jerry and Fred, with him, and within hours they had rediscovered the children's trail and hours later had found the children near death.[4] Dick-a-Dick was lauded a hero and subsequently called King Richard.[5][6] He and his tracker colleagues received a reward of £15 (equivalent to $1,142 in 2022) between them, of which £5 they could spend in whatever way they wished, while the remainder was given to their white employer to ensure it was not wasted.[4]

Sportsman[edit]

Dick-a-Dick was renowned for his skill in traditional weapons including the use of a waddy and shield. His star act was to challenge men to hit him with cricket ball thrown from 15 paces. Even when four balls were thrown at the same time, he was apparently only ever hit once, but claimed he was not ready at the time. He also always won the backwards sprint.[2][7] He protected his body and head with the shield and his legs with the waddy and would slowly move towards the men and suddenly yell, frightening everyone. A replica of Dick-a-Dick's club is held at the Lord's Cricket Ground museum.[8]

Referred to as "a famous athlete with a good running and long jumping record"[9] "He was a fine strapping, handsome fellow, and must have had an eye like a hawk to escape the flying cricket balls as he did invariably. He would glance to leg with his shield, play in the slips with his leongile, and avoid the other two balls by leaping in the air, straddling his legs, or twisting his body like lightning, this all done at once and as quick as thought."[9]

While in Melbourne, the Aboriginal cricketers were introduced to Lawn bowls. It was reported that Dick-a-Dick, along with Tarpot and Jellico, "impressed with their skill at the game."[10] Dick-a-Dick also threw a cricket ball 104 metres (341 ft)[11] in Australia, and matched that distance in England, and which was only bettered by W.G. Grace.[8]

He hurled a spear 130 metres (430 ft)[12] and won a high jump competition, clearing 1.6 metres (63 in),[13] gaining appreciation for his smooth jumping style.[14] While Cuzens was usually the fastest runner of the group, Dick-a-Dick did win a 100-yard race against all comers in Nottingham, as well as a 150-yard hurdle race, an excellent result considering he fell while attempting to clear a hurdle.[14]

Cricketer[edit]

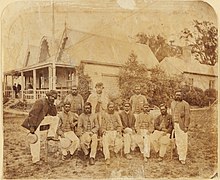

While Dick-a-Dick's skill as a cricketer was less than his other sporting endeavours, he was chosen in the Aboriginal cricket team that played matches in Victoria and New South Wales and toured England. The team uniform was white trousers, red shirts with diagonal blue sashes, blue belts and neckties, while each cricketer was given a different coloured cap; Dick-a-Dick's was yellow.[15]

While on the tour, the daughter of the Aboriginal team's manager William Hayman wrote that Dick-a-Dick had fallen in love with a local white woman, who was reported to have agreed to marry him, but Hayman opposed the marriage and forced Dick-a-Dick to continue the tour.[16] Referred to as "amiable and curious", Dick-a-Dick had a friendly disposition and was well-liked, with Charles Lawrence years later remembering him with real affection.[17]

Post-England tour[edit]

After returning from the cricket tour of England, his health deteriorated and he travelled back to his traditional country and the Ebenezer Mission. He was thought to have worked as a drover and fencer along the Murray River.[18]

White locals recognised Dick-a-Dick as a leader and elder, with one settler family recalling that he was the traditional owner of the MacKenzie Springs and Bill's Gully hunting grounds of the Wimmera,[19] and Dick-a-Dick was presented with an inscribed king plate by local European authorities.[18]

Dick-a-Dick was known by a number of names throughout his life. In addition to his birth name, Djungadjinganook, and its spelling variants Jumgumjenanuke and Jungunjinuke, he was also known as King Billy, King Dick and Kennedy (in honour of an Edenhope policeman he admired). His descendants adopted Kennedy as their surname.[18]

He died at the mission on 3 September 1870. While in Warrnambool in 1867, Dick-a-Dick was introduced to Christianity by Lawrence and appeared strongly affected by the life of Jesus.[20] He was not worried about the trip to England, as he knew the captain had prayed for a safe arrival.[21] Just before his death, he confessed his faith in Christianity and was baptised on 30 July 1870.[22] Minutes before his death, Dick-a-Dick claimed to have seen the face of Jesus.[4]

Questions about Dick-a-Dick's life[edit]

There are conflicting reports of the age of Dick-a-Dick and his date and place of death. While some sources give his date of death as 3 September 1870, there are several others which have him alive after this date. For example, a newspaper report from 1934 states that Dick-a-Dick was "about 50 years of age" when he was interviewed about his recollection of his tribe's meeting with European explorers MacPherson and Belcher in 1844.[3] If that estimate was correct, it would mean the interview had taken place in the 1880s. Additionally, in Cricket Walkabout, their book on the 1868 tour, Rex Harcourt and John Mulvaney state that he "probably died about the mid-1890s".[18]

Legacy[edit]

A book based on Dick-a-Dick's rescue of the Duff children, Lost in the Bush, was published and remained on the Victorian school curriculum for many years.[4]

A plaque commemorating the role Dick-a-Dick played in the rescue of the children was erected near Mitre Rock, Nhill, Victoria.[23]

Dick-a-Dick's great-grandson William John Kennedy was a leading activist for Australian Aboriginal causes who was named "Male Elder of the Year" at the 2003 National NAIDOC Week Awards.[24]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b c Munro, p. 54.

- ^ a b Flanagan, Martin. "Jack Kennedy: descendant of Dick-a-Dick". The Age. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- ^ a b c d The Horsham Times, "The discovery of Nhill", 2 June 1944, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d Munro, p. 55.

- ^ Broome (2005), p. 151.

- ^ Pierce, p. 22.

- ^ Broome (2001), pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b Harcourt & Mulvaney, p. 68.

- ^ a b Old 'Un, "An Old Time Team of Darkies", Euroa Advertiser, 2 April 1897, p. 3.

- ^ Harcourt & Mulvaney, p. 34.

- ^ Harcourt & Mulvaney, p. 38.

- ^ Harcourt & Delaney, p. 66.

- ^ Harcourt & Mulvaney, p. 39.

- ^ a b Harcourt & Mulvaney, p. 69.

- ^ Harcourt & Mulvaney, p. 43.

- ^ Sampson, David (2009). "Culture, 'race' and discrimination in the 1868 Aboriginal cricket tour of England". Australian Aboriginal Studies 2009. 2: 36.

- ^ Harcourt & Mulvaney, p. 46.

- ^ a b c d Harcourt & Mulvaney, p. 77.

- ^ Coutts et al. p. 12.

- ^ Harcourt & Mulvaney, pp. 44-45.

- ^ Harcourt & Mulvaney, p. 49.

- ^ Mallett, pp. 166–167.

- ^ "Dick-a-Dick". Monument Australia. Commonwealth of Australia. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- ^ "Western Vic elder wins honour". ABC. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

References[edit]

- Broome, R. (2001) Aboriginal Australians: black responses to white dominance, 1788–2001, third edition, Allen and Unwin: Sydney. ISBN 1-86508-755-6.

- Broome, R. (2005) Aboriginal Victorians: A History Since 1800, Allen & Unwin: Sydney. ISBN 1-74114-569-4.

- Coutts, A., Coutts, J. & Venables, J. (1937) Back to Bill's Gully and Yanipy, self pub.

- Harcourt, R. & Mulvaney, J. (2005) Cricket Walkabout, Golden Point Press: Blackburn South. ISBN 09757673 0 5.

- Mallett, A. (2002) The black lords of summer: the story of the 1868 Aboriginal tour of England and Beyond, University of Queensland Press: St Lucia. ISBN 0-7022-3262-9.

- Munro, C. "Making tracks", Tracker, New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council. July 2011.

- Pierce, P. (1999) The country of lost children: an Australian anxiety, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-59440-5.