Eszopiclone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Lunesta, Eszop, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605009 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth (tablets) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 52–59% |

| Metabolism | Liver oxidation and demethylation (CYP3A4 and CYP2E1-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 6 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.149.304 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

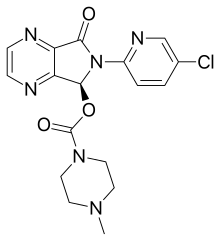

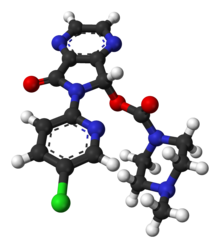

| Formula | C17H17ClN6O3 |

| Molar mass | 388.81 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Eszopiclone, sold under the brand-name Lunesta among others such as Night Calm in Egypt, is a medication used in the treatment of insomnia.[3] Evidence supports slight to moderate benefit up to six months.[4][3][5] It is taken orally.[4]

Common side effects include headache, dry mouth, nausea, and dizziness.[4] Severe side effects may include suicidal thoughts, unhealthy non-medical use, hallucinations, and angioedema.[4] Greater care is recommended in those with liver problems and older people.[4] Rapid decreasing of the dose may result in withdrawal.[4] Eszopiclone is classified as a nonbenzodiazepine sedative hypnotic and as a cyclopyrrolone.[6] It is the S-stereoisomer of zopiclone.[4][7] It works by interacting with the GABA receptors.[6]

Approved for medical use in the United States in 2004, eszopiclone is available as generic medication.[4] In 2020, it was the 232nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 1 million prescriptions.[8][9] Eszopiclone is not sold in the European Union, as of 2009 the European Medicines Agency (EMA) ruled that it was too similar to zopiclone to be considered a new patentable product.[10][11][12]

Medical uses

A 2018 Cochrane review found that it produced moderate improvement in sleep onset and maintenance. The authors suggest that where preferred non-pharmacological treatment strategies have been exhausted, eszopiclone provides an efficient treatment for insomnia.[13] In 2014, the USFDA asked that the starting dose be lowered from 2 milligrams to 1 milligram after it was observed in a study that even 8 hours after taking the drug at night, some people were not able to cope with their next-day activities like driving and other activities that require full alertness.[citation needed]

Eszopiclone is slightly effective in the treatment of insomnia where difficulty in falling asleep is the primary complaint.[3] Kirsch et al. found the benefit over placebo to be of questionable clinical significance.[3] Although the drug effect and the placebo response were rather small and of questionable clinical importance, the two together produce a reasonably large clinical response.[3] It is not recommended for chronic use in the elderly.[14]

Elderly

Sedative hypnotic drugs including eszopiclone are more commonly prescribed to the elderly than to younger patients despite benefits of medication being generally unimpressive. Care should be taken in choosing an appropriate hypnotic drug and if drug therapy is initiated it should be initiated at the lowest possible dose to minimise side effects.[15]

In 2015, the American Geriatrics Society reviewed the safety information about eszopiclone and similar drugs and concluded that the "nonbenzodiazepine, benzodiazepine receptor agonist hypnotics (eszopiclone, zaleplon, zolpidem) are to be avoided without consideration of duration of use because of their association with harms balanced with their minimal efficacy in treating insomnia."

The review made this determination both because of the relatively large dangers to elderly individuals from zolpidem and other "z-drugs" together with the fact the drugs have "minimal efficacy in treating insomnia." This was a change from the 2012 AGS recommendation, which suggested limiting use to 90 days or less. The review stated: "the 90‐day‐use caveat [was] removed from nonbenzodiazepine, benzodiazepine receptor agonist hypnotics, resulting in an unambiguous 'avoid' statement (without caveats) because of the increase in the evidence of harm in this area since the 2012 update."[16]

An extensive review of the medical literature regarding the management of insomnia and the elderly found that there is considerable evidence of the effectiveness and durability of non-drug treatments for insomnia in adults of all ages and that these interventions are underutilized. Compared with the benzodiazepines, the nonbenzodiazepine sedative-hypnotics, including eszopiclone appeared to offer few, if any, significant clinical advantages in efficacy or tolerability in elderly persons. It was found that newer agents with novel mechanisms of action and improved safety profiles, such as the melatonin receptor agonists, hold promise for the management of chronic insomnia in elderly people. Long-term use of sedative-hypnotics for insomnia lacks an evidence base and has traditionally been discouraged for reasons that include concerns about such potential adverse drug effects as cognitive impairment (anterograde amnesia), daytime sedation, motor incoordination, and increased risk of motor vehicle accidents and falls. In addition, the effectiveness and safety of long-term use of these agents remain to be determined. It was concluded that more research is needed to evaluate the long-term effects of treatment and the most appropriate management strategy for elderly persons with chronic insomnia.[17]

A 2009 meta-analysis found a higher rate of infections.[18]

Adverse effects

Sleeping pills, including eszopiclone, have been associated with an increased risk of death.[19]

Hypersensitivity to eszopiclone is a contra-indication to its use. Some side effects are more common than others. Recommendations around use of eszopiclone may be altered by other health conditions. These conditions or circumstances may occur in people that have lowered metabolism and other conditions. The presence of liver impairment, lactation and activities requiring mental alertness (e.g., driving) may be considered when determining frequency and dosage.[6]

- unpleasant taste[6]

- headache[6]

- peripheral edema[6][20]

- chest pain[6]

- abnormal thinking[6]

- behavior changes[6]

- depression[6][20]

- hallucinations[6][20]

- sleep driving[6] and sleepwalking

- dry mouth[6]

- rash[6][20]

- altered sleep patterns[6]

- impaired coordination[6]

- dizziness[6]

- daytime drowsiness[6]

- itching[20]

- painful or frequent urination[20]

- back pain[20]

- aggressive behavior[20]

- confusion[20]

- agitation[20]

- suicidal thoughts[20]

- depersonalisation[20]

- amnesia[20]

A 2009 meta-analysis found a 44% higher rate of mild infections, such as pharyngitis or sinusitis, in people taking eszopiclone or other hypnotic drugs compared to those taking a placebo.[21]

Dependence

In the United States eszopiclone is a schedule IV controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act. Use of eszopiclone may lead to physical and psychological dependence.[6][22] The risk of non-medical use and dependence increases with the dose and duration of usage and concomitant use of other psychoactive substances. The risk is also greater in patients with a history of alcohol use disorder or other substance use disorder or history of psychiatric disorders. Tolerance may develop after repeated use of benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine-like drugs for a few weeks.

A study funded and carried out by Sepracor, the manufacturer of eszopiclone, found no signs of tolerance or dependence in a group of patients followed for up to six months.[22]

Non-medical use

A study of non-medical use potential of eszopiclone found that in persons with a known history of non-medical benzodiazepine use, eszopiclone at doses of 6 and 12 mg produced effects similar to those of diazepam 20 mg. The study found that at these doses which are two or more times greater than the maximum recommended doses, a dose-related increase in reports of amnesia, sedation, sleepiness, and hallucinations was observed for both eszopiclone (Lunesta) as well as for diazepam (Valium).[20]

Overdose

According to the U.S. Prescribing Information, overdoses of eszopiclone up to 90 times the recommended dose have been reported in which the patient fully recovered. According to the May 2014 edition of the official U.S. Prescribing Information, fatalities have been reported only in cases in which eszopiclone was combined with other drugs or alcohol.[23]

Poison control centers reported that between 2005 and 2006 there were 525 total eszopiclone overdoses recorded in the state of Texas, the majority of which were intentional suicide attempts.[24]

If consumed within the last hour, eszopiclone overdose can be treated with the administration of activated charcoal or via gastric lavage.[25]

Interactions

There is an increased risk of central nervous system depression when eszopiclone is taken together with other CNS depressant agents, including antipsychotics, sedative hypnotics (like barbiturates or benzodiazepines), antihistamines, opioids, phenothiazines, and some antidepressants. There is also increased risk of central nervous system depression with other medications that inhibit the metabolic activities of the CYP3A4 enzyme system of the liver. Medications that inhibit this enzyme system include nelfinavir, ritonavir, ketoconazole, itraconazole and clarithromycin. Alcohol also has an additive effect when used concurrently with eszopiclone.[6] Eszopiclone is most effective if it is not taken after a heavy meal with high fat content.[6]

Pharmacology

Eszopiclone acts on benzodiazepine binding site situated on GABAA neurons as a positive allosteric modulator.[26] Eszopiclone is rapidly absorbed after oral administration, with serum levels peaking between .45 and 1.3 hours.[27][6] The elimination half-life of eszopiclone is approximately 6 hours and it is extensively metabolized by oxidation and demethylation. Approximately 52% to 59% of a dose is weakly bound to plasma protein. Cytochrome P450 (CYP) isozymes CYP3A4 and CYP2E1 are involved in the biotransformation of eszopiclone; thus, drugs that induce or inhibit these CYP isozymes may affect the metabolism of eszopiclone. Less than 10% of the orally administered dose is excreted in the urine as racemic zopiclone.[28][29] In terms of benzodiazepine receptor binding and relevant potency, 3 mg of eszopiclone is equivalent to 10 mg of diazepam.[30]

History

In a controversial 2009 article in the New England Journal of Medicine, "Lost in Transmission — FDA Drug Information That Never Reaches Clinicians", it was reported that the largest of three Lunesta trials found that compared to placebo Lunesta "was superior to placebo" while it only shortened initial time falling asleep by 15 minutes on average. "Clinicians who are interested in the drug’s efficacy cannot find efficacy information in the label: it states only that Lunesta is superior to placebo. The FDA’s medical review provides efficacy data, albeit not until page 306 of the 403-page document. In the longest, largest phase 3 trial, patients in the Lunesta group reported falling asleep an average of 15 minutes faster and sleeping an average of 37 minutes longer than those in the placebo group. However, on average, Lunesta patients still met criteria for insomnia and reported no clinically meaningful improvement in next-day alertness or functioning."[31]

Availability in Europe

On September 11, 2007, Sepracor signed a marketing deal with British pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline for the rights to sell eszopiclone (under the name Lunivia rather than Lunesta) in Europe.[32] Sepracor was expected to receive approximately $155 million if the deal went through.[32] In 2008 Sepracor submitted an application to the EMA (the European Union's equivalent to the U.S. FDA) for authorization to market the drug in the EU, and initially received a favorable response.[33] However, Sepracor withdrew its authorization application in 2009 after the EMA stated it would not be granting eszopiclone 'new active substance' status, as it was essentially pharmacologically and therapeutically too similar to zopiclone to be considered a new patentable product.[34] Since the patent on zopiclone has expired, this ruling would have allowed rival companies to also legally produce cheaper generic versions of eszopiclone for the European market.[35] As of November 2012[update], Sepracor has not resubmitted its authorization application and eszopiclone is not available in Europe. The deal with GSK fell through, and GSK instead launched a $3.3 billion deal to market Actelion's almorexant sleeping tablet, which entered phase 3 medical trials before development was abandoned due to side effects.[36][citation needed]

References

- ^ WHO International Working Group for Drug Statistics Methodology (August 27, 2008). "ATC/DDD Classification (FINAL): New ATC 5th level codes". WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Archived from the original on 2008-05-06. Retrieved 2008-09-05.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Huedo-Medina, TB; Kirsch, I; Middlemass, J; Klonizakis, M; Siriwardena, AN (Dec 17, 2012). "Effectiveness of non-benzodiazepine hypnotics in treatment of adult insomnia: meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 345: e8343. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8343. PMC 3544552. PMID 23248080.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Eszopiclone Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ Rösner, S; Englbrecht, C; Wehrle, R; Hajak, G; Soyka, M (10 October 2018). "Eszopiclone for insomnia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (10): CD010703. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010703.pub2. PMC 6492503. PMID 30303519.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "Eszopiclone" (PDF). F.A. Davis. 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ Rösner, Susanne; Englbrecht, Christian; Wehrle, Renate; Hajak, Göran; Soyka, Michael (2018-10-10). "Eszopiclone for insomnia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (10): CD010703. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010703.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6492503. PMID 30303519.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Eszopiclone - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "End of Sepracor-GSK Deal Raises Question in Lunesta Patent Fight". www.cbsnews.com. 13 June 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ "Guide to Zopiclone tablets". fastukmeds.com. Retrieved 2021-08-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Sepracor Pharmaceuticals Ltd withdraws its marketing authorisation application for Lunivia (eszopiclone)". European Medicines Agency. 15 June 2009. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ Rösner, Susanne; Englbrecht, Christian; Wehrle, Renate; Hajak, Göran; Soyka, Michael (10 October 2018). "Eszopiclone for insomnia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (10): CD010703. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010703.pub2. PMC 6492503. PMID 30303519.

- ^ American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert, Panel (April 2012). "American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 60 (4): 616–31. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. PMC 3571677. PMID 22376048.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Tariq SH, Pulisetty S (February 2008). "Pharmacotherapy for insomnia". Clin Geriatr Med. 24 (1): 93–105, vii. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2007.08.009. PMID 18035234.

- ^ Fick DM, Semla TP, Beizer J, Brandt N (2015). "American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults" (PDF). Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 63 (11): 2227–2246. doi:10.1111/jgs.13702. PMID 26446832. S2CID 38797655.

- ^ Bain KT (June 2006). "Management of chronic insomnia in elderly persons". Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 4 (2): 168–92. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.06.006. PMID 16860264.

- ^ Joya FL, Kripke DF, Loving RT, Dawson A (2009). "Meta-Analyses of Hypnotics and Infections: eszopiclone, ramelteon, zaleplon, and zolpidem". J. Clin. Sleep Med. 5 (4): 377–83. doi:10.5664/jcsm.27552. PMC 2725260. PMID 19968019.

- ^ Kripke, DF (February 2016). "Mortality Risk of Hypnotics: Strengths and Limits of Evidence" (PDF). Drug Safety. 39 (2): 93–107. doi:10.1007/s40264-015-0362-0. PMID 26563222. S2CID 7946506.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Rxlist (26 October 2016). "Lunesta". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- ^ Joya, FL; Kripke, DF; Loving, RT; Dawson, A; Kline, LE (2009). "Meta-Analyses of Hypnotics and Infections: Eszopiclone, Ramelteon, Zaleplon, and Zolpidem". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 5 (4): 377–383. doi:10.5664/jcsm.27552. PMC 2725260. PMID 19968019.

- ^ a b Brielmaier BD (January 2006). "Eszopiclone (Lunesta): a new nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic agent". Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 19 (1): 54–9. doi:10.1080/08998280.2006.11928127. PMC 1325284. PMID 16424933.

- ^ "Lunesta Prescribing Information at Drugs@FDA" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-05-22.

- ^ Forrester MB (October 2007). "Eszopiclone ingestions reported to Texas poison control centers, 2005 2006". Hum Exp Toxicol. 26 (10): 795–800. doi:10.1177/0960327107084045. PMID 18025051. S2CID 25102558.

- ^ "Zopiclone overdose". MHRA. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Archived from the original on December 6, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) (From archive 6 Dec 2014) - ^ Jufe GS (July–August 2007). "[New hypnotics: perspectives from sleep physiology]". Vertex. 18 (74): 294–9. PMID 18265473.

- ^ Halas CJ (January 1, 2006). "Eszopiclone". Am J Health Syst Pharm. 63 (1): 41–8. doi:10.2146/ajhp050357. PMID 16373464.

- ^ Najib J (April 2006). "Eszopiclone, a non-benzodiazepine sedative-hypnotic agent for the treatment of transient and chronic insomnia". Clin Ther. 28 (4): 491–516. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.04.014. PMID 16750462.

- ^ Morinan, Alun; Keaney, Francis (2010-12-10). "Long-term misuse of zopiclone in an alcohol dependent woman with a history of anorexia nervosa: a case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 4 (1): 403. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-4-403. ISSN 1752-1947. PMC 3014964. PMID 21143957.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Professor Ashton (April 2007). "Benzodiazepine Equivalence Table". Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- ^ Schwartz, Lisa M.; Steven Woloshin (October 2009). "Lost in Transmission — FDA Drug Information That Never Reaches Clinicians". New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (18): 1717–1720. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0907708. PMID 19846841. Archived from the original (Online) on 2010-10-27. Retrieved 2010-12-06.

- ^ a b "GlaxoSmithKline and Sepracor Inc. announce international alliance for commercialisation of Lunivia". Archived from the original on December 27, 2010.

- ^ Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use – Summary of Positive Opinion for Lunivia – European Medicines Agency/Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use, 23 Oct 2010

- ^ Sepracor Pharmaceuticals Ltd withdraws its marketing authorisation application for Lunivia (eszopiclone) Archived 2017-12-01 at the Wayback Machine – European Medicines Agency, 15 May 2009

- ^ Data exclusivity and definition of a new active substance: suspension of generic escitalopram-containing medicines by CHMP – Bird and Bird Commercial Law 23 Apr 2010

- ^ "Almorexant for Treatment of Primary Insomnia - Clinical Trials Arena". www.clinicaltrialsarena.com. Retrieved 2021-08-04.

External links

- "Eszopiclone". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.