Trichlorofluoromethane

This article needs to be updated. (October 2023) |

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Trichloro(fluoro)methane | |||

| Other names

Trichlorofluoromethane

Fluorotrichloromethane Fluorochloroform Freon 11 CFC 11 R 11 Arcton 9 Freon 11A Freon 11B Freon HE Freon MF | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.812 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| CCl3F | |||

| Molar mass | 137.36 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless liquid/gas | ||

| Odor | nearly odorless[1] | ||

| Density | 1.494 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | −110.48 °C (−166.86 °F; 162.67 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 23.77 °C (74.79 °F; 296.92 K) | ||

| 1.1 g/L (at 20 °C) | |||

| log P | 2.53 | ||

| Vapor pressure | 89 kPa at 20 °C 131 kPa at 30 °C | ||

| Thermal conductivity | 0.0079 W m−1 K−1 (gas at 300 K, ignoring pressure dependence)[2][verification needed] | ||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling:[4] | |||

| |||

| Warning | |||

| H420 | |||

| P502 | |||

| Flash point | Non-flammable | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LCLo (lowest published)

|

26,200 ppm (rat, 4 hr) 100,000 ppm (rat, 20 min) 100,000 ppm (rat, 2 hr)[3] | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 1000 ppm (5600 mg/m3)[1] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

C 1000 ppm (5600 mg/m3)[1] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

2000 ppm[1] | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 0047 | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

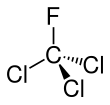

Trichlorofluoromethane, also called freon-11, CFC-11, or R-11, is a chlorofluorocarbon (CFC). It is a colorless, faintly ethereal, and sweetish-smelling liquid that boils around room temperature.[5] CFC-11 is a Class 1 ozone-depleting substance which damages Earth's protective stratospheric ozone layer.[6] R-11 is not flammable at ambient temperature and pressure but it can become very combustible if heated and ignited by a strong ignition source.

Historical use

[edit]Trichlorofluoromethane was first widely used as a refrigerant. Because of its high boiling point compared to most refrigerants, it can be used in systems with a low operating pressure, making the mechanical design of such systems less demanding than that of higher-pressure refrigerants R-12 or R-22.

Trichlorofluoromethane is used as a reference compound for fluorine-19 NMR studies.

Trichlorofluoromethane was formerly used in the drinking bird novelty, largely because it has a boiling point of 23.77 °C (74.79 °F). The replacement, dichloromethane, boiling point 39.6 °C (103.3 °F), requires a higher ambient temperature to work.

Prior to the knowledge of the ozone depletion potential of chlorine in refrigerants and other possible harmful effects on the environment, trichlorofluoromethane was sometimes used as a cleaning/rinsing agent for low-pressure systems.[7]

Production

[edit]Trichlorofluoromethane can be obtained by reacting carbon tetrachloride with hydrogen fluoride at 435 °C and 70 atm, producing a mixture of trichlorofluoromethane, tetrafluoromethane and dichlorodifluoromethane in a ratio of 77:18:5. The reaction can also be carried out in the presence of antimony(III) chloride or antimony(V) chloride:[8]

Trichlorofluoromethane is also formed as one of the byproducts when graphite reacts with chlorine and hydrogen fluoride at 500 °C.[8]

Sodium hexafluorosilicate under pressure at 270 °C, titanium(IV) fluoride, chlorine trifluoride, cobalt(III) fluoride, iodine pentafluoride, and bromine trifluoride are also suitable fluorinating agents for carbon tetrachloride.[8][9]

Trichlorofluoromethane was included in the production moratorium in the Montreal Protocol of 1987. It is assigned an ozone depletion potential of 1.0, and U.S. production was ended on January 1, 1996.[6]

Regulatory challenges

[edit]In 2018, the atmospheric concentration of CFC-11 was noted by researchers to be declining more slowly than expected,[10][11] and it subsequently emerged that it remains in widespread use as a blowing agent for polyurethane foam insulation in the construction industry of China.[12] In 2021, researchers announced that emissions declined by 20,000 U.S. tons from 2018 to 2019, which mostly reversed the previous spike in emissions.[13] In 2022, the European Commission announced an updated regulation that mandates the recovery and prevention of emissions of CFC-11 blowing agents from foam insulation in demolition waste, which is still emitted at significant scale.[14]

Dangers

[edit]R11, like most chlorofluorocarbons, forms phosgene gas when exposed to a naked flame.[15]

Use in Planetary Astrophysics

[edit]Because trichlorofluoromethane is one of the easiest to detect chlorofluorocarbons produced by anthropogenic activity, it is has been used in detecting industrial pollution in the atmospheres of earth-like exoplanets.[16]

Gallery

[edit]-

CFC-11 measured by the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE) in the lower atmosphere (troposphere) at stations around the world. Abundances are given as pollution free monthly mean mole fractions in parts-per-trillion.

-

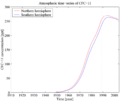

Hemispheric and Global mean concentrations of CFC-11 (NOAA/ESRL)

-

Time-series of atmospheric concentrations of CFC-11 (Walker et al., 2000)

-

"Present day" (1990s) sea surface CFC-11 concentration

-

"Present day" (1990s) CFC-11 oceanic vertical inventory

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0290". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Touloukian, Y.S., Liley, P.E., and Saxena, S.C. Thermophysical properties of matter - the TPRC data series. Volume 3. Thermal conductivity - nonmetallic liquids and gases. Data book. 1970.

- ^ "Fluorotrichloromethane". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Record in the GESTIS Substance Database of the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- ^ Siegemund, Günter; Schwertfeger, Werner; Feiring, Andrew; Smart, Bruce; Behr, Fred; Vogel, Herward; McKusick, Blaine (2002). "Fluorine Compounds, Organic". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_349. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ a b "International Treaties and Cooperation about the Protection of the Stratospheric Ozone Layer". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 15 July 2015. Retrieved 2021-02-14.

- ^ "R-10 ,R-11 ,R-12 GASES - ملتقى التبريد والتكييف HVACafe". ملتقى التبريد والتكييف HVACafe (in Arabic). 2017-05-25. Archived from the original on 2018-05-18. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- ^ a b c Katritzky, Alan R.; Gilchrist, Thomas L.; Meth-Cohn, Otto; Rees, Charles Wayne (1995), Comprehensive Organic Functional Group Transformations, Elsevier, p. 220, ISBN 978-0-08-042704-1 – via Google Books

- ^ Banks, A.A.; Emeléus, H.J.; Haszeldine, R. N.; Kerrigan, V. (December 1948). "443. The reaction of bromine trifluoride and iodine pentafluoride with carbon tetrachloride, tetrabromide, and tetraiodide and with tetraiodoethylene". Journal of the Chemical Society: 2188–2190. doi:10.1039/JR9480002188.

- ^ Montzka SA, Dutton GS, Yu P, et al. (2018). "An unexpected and persistent increase in global emissions of ozone-depleting CFC-11". Nature. 557 (7705). Springer Nature: 413–417. Bibcode:2018Natur.557..413M. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0106-2. hdl:1983/fd5eaf00-34b1-4689-9f23-410a54182b61. PMID 29769666. S2CID 21705434.

- ^ Johnson, Scott (5 May 2018). "It seems someone is producing a banned ozone-depleting chemical again". Ars Technica. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

Decline of CFC-11 has slowed in recent years, pointing to a renewed source

- ^ McGrath, Matt (9 July 2018). "China 'home foam' gas key to ozone mystery". BBC News. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ Chu, Jennifer (2021-02-10). "Reductions in CFC-11 emissions put ozone recovery back on track". MIT News.

- ^ "Proposal for a regulation of the european parliament and the council on substances that deplete the ozone layer" (PDF). European Commission. European Commission-DG Environment. 2022-05-04. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- ^ Orr, Bryan (4 January 2021). "False Alarms: The Legacy of Phosgene Gas". HVAC School. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Lin, Henry W.; Abad, Gonzalo Gonzalez; Loeb, Abraham (2014-08-12). "Detecting industrial pollution in the atmospheres of earth-like exoplanets". The Astrophysical Journal. 792 (1): L7. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/792/1/L7. ISSN 2041-8213.

External links

[edit]- CFC-11 NOAA/ESRL Global measurements

- Public health goal for trichlorofluoromethane in drinking water

- Names at webbook.nist.gov

- Data sheet at speclab.com Archived 2007-06-09 at the Wayback Machine

- International Chemical Safety Card 0047

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0290". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Phase change data at webbook.nist.gov

- Thermochemistry data at chemnet.ru

- ChemSub Online: Trichlorofluoromethane - CFC-11

- materialsproject.org