Fourteen Points

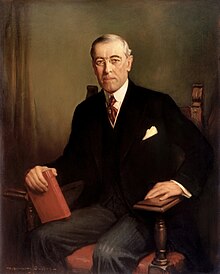

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to the United States Congress by President Woodrow Wilson. However, his main Allied colleagues (Georges Clemenceau of France, David Lloyd George of the United Kingdom, and Vittorio Emanuele Orlando of Italy) were skeptical of the applicability of Wilsonian idealism.[1]

The United States had joined the Triple Entente in fighting the Central Powers on April 6, 1917. Its entry into the war had in part been due to Germany's resumption of submarine warfare against merchant ships trading with France and Britain and also the interception of the Zimmermann Telegram. However, Wilson wanted to avoid the United States' involvement in the long-standing European tensions between the great powers; if America was going to fight, he wanted to try to separate that participation in the war from nationalistic disputes or ambitions. The need for moral aims was made more important when, after the fall of the Russian government, the Bolsheviks disclosed secret treaties made between the Allies. Wilson's speech also responded to Vladimir Lenin's Decree on Peace of November 1917, immediately after the October Revolution in 1917.[2]

The speech made by Wilson took many domestic progressive ideas and translated them into foreign policy (free trade, open agreements, democracy and self-determination). Three days earlier United Kingdom Prime Minister Lloyd George had made a speech setting out the UK's war aims which bore some similarity to Wilson's speech but which proposed reparations be paid by the Central Powers and which was more vague in its promises to the non-Turkish subjects of the Ottoman Empire. The Fourteen Points in the speech were based on the research of the Inquiry, a team of about 150 advisers led by foreign-policy adviser Edward M. House, into the topics likely to arise in the anticipated peace conference.

Background

The immediate cause of the United States' entry into World War I in April 1917 was the German announcement of renewed unrestricted submarine warfare and the subsequent sinking of ships with Americans on board. But President Wilson's war aims went beyond the defense of maritime interests. In his War Message to Congress, Wilson declared that the United States' objective was "to vindicate the principles of peace and justice in the life of the world." In several speeches earlier in the year, Wilson sketched out his vision of an end to the war that would bring a "just and secure peace," not merely "a new balance of power."[3]

President Wilson subsequently initiated a secret series of studies named the Inquiry, primarily focused on Europe, and carried out by a group in New York which included geographers, historians and political scientists; the group was directed by Edward M. House.[4] Their job was to study Allied and American policy in virtually every region of the globe and analyze economic, social, and political facts likely to come up in discussions during the peace conference.[5] The group produced and collected nearly 2,000 separate reports and documents plus at least 1,200 maps.[5] The studies culminated in a speech by Wilson to Congress on January 8, 1918, wherein he articulated America's long-term war objectives. The speech was the clearest expression of intention made by any of the belligerent nations, and it projected Wilson's progressive domestic policies into the international arena.[4]

Speech

The speech, known as the Fourteen Points, was developed from a set of diplomatic points by Wilson[6] and territorial points drafted by the Inquiry's general secretary, Walter Lippmann, and his colleagues, Isaiah Bowman, Sidney Mezes, and David Hunter Miller.[7] Lippmann's draft territorial points were a direct response to the secret treaties of the European Allies, which Lippmann had been shown by Secretary of War Newton D. Baker.[7] Lippmann's task, according to House, was "to take the secret treaties, analyze the parts which were tolerable, and separate them from those which were regarded as intolerable, and then develop a position which conceded as much to the Allies as it could, but took away the poison.... It was all keyed upon the secret treaties."[7]

In the speech, Wilson directly addressed what he perceived as the causes for the world war by calling for the abolition of secret treaties, a reduction in armaments, an adjustment in colonial claims in the interests of both native peoples and colonists, and freedom of the seas.[5] Wilson also made proposals that would ensure world peace in the future. For example, he proposed the removal of economic barriers between nations, the promise of self-determination for national minorities,[5] and a world organization that would guarantee the "political independence and territorial integrity [of] great and small states alike" – a League of Nations.[3]

Though Wilson's idealism pervaded the Fourteen Points, he also had more practical objectives in mind. He hoped to keep Russia in the war by convincing the Bolsheviks that they would receive a better peace from the Allies, to bolster Allied morale, and to undermine German war support. The address was well received in the United States and Allied nations and even by Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin, as a landmark of enlightenment in international relations. Wilson subsequently used the Fourteen Points as the basis for negotiating the Treaty of Versailles, which ended the war.[3]

Text

In his speech to Congress, President Wilson declared fourteen points which he regarded as the only possible basis of an enduring peace:[9]

I. Open covenants of peace, openly arrived at, after which there shall be no private international understandings of any kind but diplomacy shall proceed always frankly and in the public view.

II. Absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas, outside territorial waters, alike in peace and in war, except as the seas may be closed in whole or in part by international action for the enforcement of international covenants.

III. The removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers and the establishment of an equality of trade conditions among all the nations consenting to the peace and associating themselves for its maintenance.

IV. Adequate guarantees given and taken that national armaments will be reduced to the lowest point consistent with domestic safety.

V. A free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the populations concerned must have equal weight with the equitable government whose title is to be determined.

VI. The evacuation of all Russian territory and such a settlement of all questions affecting Russia as will secure the best and freest cooperation of the other nations of the world in obtaining for her an unhampered and unembarrassed opportunity for the independent determination of her own political development and national policy and assure her of a sincere welcome into the society of free nations under institutions of her own choosing; and, more than a welcome, assistance also of every kind that she may need and may herself desire. The treatment accorded Russia by her sister nations in the months to come will be the acid test of their good will, of their comprehension of her needs as distinguished from their own interests, and of their intelligent and unselfish sympathy.

VII. Belgium, the whole world will agree, must be evacuated and restored, without any attempt to limit the sovereignty which she enjoys in common with all other free nations. No other single act will serve as this will serve to restore confidence among the nations in the laws which they have themselves set and determined for the government of their relations with one another. Without this healing act the whole structure and validity of international law is forever impaired.

VIII. All French territory should be freed and the invaded portions restored, and the wrong done to France by Prussia in 1871 in the matter of Alsace-Lorraine, which has unsettled the peace of the world for nearly fifty years, should be righted, in order that peace may once more be made secure in the interest of all.

IX. A readjustment of the frontiers of Italy should be effected along clearly recognizable lines of nationality.

X. The people of Austria-Hungary, whose place among the nations we wish to see safeguarded and assured, should be accorded the freest opportunity to autonomous development.[10]

XI. Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro should be evacuated; occupied territories restored; Serbia accorded free and secure access to the sea; and the relations of the several Balkan states to one another determined by friendly counsel along historically established lines of allegiance and nationality; and international guarantees of the political and economic independence and territorial integrity of the several Balkan states should be entered into.

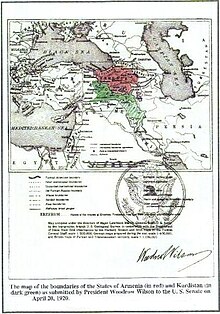

XII. The Turkish portion of the present Ottoman Empire should be assured a secure sovereignty, but the other nationalities which are now under Ottoman rule should be assured an undoubted security of life and an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development, and the Dardanelles should be permanently opened as a free passage to the ships and commerce of all nations under international guarantees.

XIII. An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant.

XIV. A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.

Reaction

Allies

Wilson at first considered abandoning his speech after Lloyd George delivered a speech outlining British war aims, many of which were similar to Wilson's aspirations, at Caxton Hall on January 5, 1918. Lloyd George stated that he had consulted leaders of "the Great Dominions overseas" before making his speech, so it would appear that Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Newfoundland were in broad agreement.[11]

Wilson was persuaded by his adviser House to go ahead, and Wilson's speech overshadowed Lloyd George's and is better remembered by posterity.[12]

The speech was made without prior coordination or consultation with Wilson's counterparts in Europe. Clemenceau, upon hearing of the Fourteen Points, was said to have sarcastically proclaimed, "The good Lord had only ten!" (Le bon Dieu n'en avait que dix !). As a major public statement of war aims, it became the basis for the terms of the German surrender at the end of the First World War. After the speech, House worked to secure the acceptance of the Fourteen Points by Entente leaders. On October 16, 1918, President Woodrow Wilson and Sir William Wiseman, the head of British intelligence in America, had an interview. This interview was one reason why the German government accepted the Fourteen Points and the stated principles for peace negotiations.[citation needed]

The report was made as negotiation points, and the Fourteen Points were later accepted by France and Italy on November 1, 1918. Britain later signed off on all of the points except the freedom of the seas.[13] The United Kingdom also wanted Germany to make reparation payments for the war, and thought that should be added to the Fourteen Points. The speech was delivered 10 months before the Armistice with Germany and became the basis for the terms of the German surrender, as negotiated at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919.[14]

Central Powers

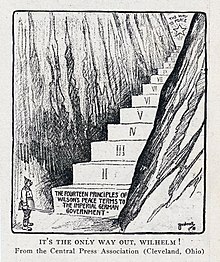

The speech was widely disseminated as an instrument of Allied propaganda and was translated into many languages for global dissemination.[15] Copies were also dropped behind German lines, to encourage the Central Powers to surrender in the expectation of a just settlement.[5] Indeed, in a note sent to Wilson, Prince Maximilian of Baden, the German imperial chancellor, in October 1918 requested an immediate armistice and peace negotiations on the basis of the Fourteen Points.[16]

United States

Theodore Roosevelt, in a January 1919 article titled, "The League of Nations", published in Metropolitan Magazine, warned: "If the League of Nations is built on a document as high-sounding and as meaningless as the speech in which Mr. Wilson laid down his fourteen points, it will simply add one more scrap to the diplomatic waste paper basket. Most of these fourteen points... would be interpreted... to mean anything or nothing."[17]

Senator William Borah after 1918 wished "this treacherous and treasonable scheme" of the League of Nations to be "buried in hell" and promised that if he had his way it would be "20,000 leagues under the sea".[18]

Other countries

Wilson's speech regarding the Fourteen Points led to unintentional but important consequences in regards to countries which were under European colonial rule or under the influence of European countries. In many of the Fourteen Points, specifically points X, XI, XII and XIII, Wilson had focused on adjusting colonial disputes and the importance of allowing autonomous development and self-determination. This drew significant attention from anti-colonial nationalist leaders and movements, who saw Wilson's swift adoption of the term "self-determination" (although he did not actually use the term in the speech itself) as an opportunity to gain independence from colonial rule or expel foreign influence.[19]

Consequently, Wilson gained support from anti-colonial nationalist leaders in Europe's colonies and countries under European influence around the globe who were hopeful that Wilson would assist them in their goals. Around the world, Wilson was occasionally elevated to a quasi-religious figure; as someone who was an agent of salvation and a bringer of peace and justice.[19] During this 'Wilsonian moment', there was considerable optimism among anti-colonial nationalist leaders and movements that Wilson and the Fourteen Points were going to be an influential force that would re-shape the long established relationships between the West and the rest of the world.[19] Many of them believed that the United States, given its history (particularly the American Revolution) would be sympathetic towards the goals and aspirations they held. A common belief among anti-colonial nationalist leaders was the U.S., once it had assisted them in gaining independence from colonial rule or foreign influence, would establish new relationships which would be more favorable and equitable than what had existed beforehand.[19]

However, the nationalist interpretations of both the Fourteen Points and Wilson's views regarding colonialism proved to be misguided. In actuality, Wilson had never established a goal of opposing European colonial powers and breaking up their empires, nor was he trying to fuel anti-colonial nationalist independence movements. It was not Wilson's objective or desire to confront European colonial powers over such matters, as Wilson had no intention of supporting any demands for self-determination and sovereignty that conflicted with the interests of the victorious Allies.[19]

In reality, Wilson's calls for greater autonomous development and sovereignty had been aimed solely at European countries under the rule of the German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires. He did not explicitly outline this, although it is clear that his calls for greater sovereignty in these regions was in an effort to try and destabilise those enemies' empires.[19] President Wilson's ambitions for the third world were rather to attempt to influence its development in order to transform it from 'backward' to 'sophisticated', the aim being to incorporate it into the commercial world, so that the U.S could further benefit from trade with the global south.[20] Furthermore, Wilson did not believe the third world was ready for self governance, asserting that a period of trusteeship and tutelage from colonial powers was required to manage such a transition. Wilson viewed this approach as essential to the 'proper development' of colonised countries, reflecting his views about the inferiority of the non-European races.[20] Moreover, Wilson was not by character or background an anti-colonialist or campaigner for rights and freedoms for all people, instead he was also very much a racist, a fundamental believer in white supremacy.[20] For example, he had supported the 1898 U.S annexation of the Philippines whilst condemning the rebellion of the Philippine nationalist Emilio Aguinaldo, and strongly believed that the U.S was morally obliged to impose Western ways of life and governance on such countries, so that eventually they could govern independently.[20]

Treaty of Versailles

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2019) |

President Wilson contracted Spanish flu at the beginning of the Paris Peace Conference and became severely ill with high fevers and bouts of delirium[21] giving way to French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau to advance demands that were substantially different from Wilson's Fourteen Points. Clemenceau viewed Germany as having unfairly attained an economic victory over France because of the heavy damage German forces dealt to France's industries even during the German retreat, and he expressed dissatisfaction with France's allies at the peace conference.

Notably, Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles, which would become known as the War Guilt Clause, was seen by the Germans as assigning full responsibility for the war and its damages on Germany; however, the same clause was included in all peace treaties and historian Sally Marks has noted that only German diplomats saw it as assigning responsibility for the war. The Allies would initially assess 269 billion marks in reparations. In 1921, this figure was established at 192 billion marks. However, only a fraction of the total had to be paid. The figure was designed to look imposing and show the public that Germany was being punished, but it also recognized what Germany could not realistically pay.

Germany's ability and willingness to pay that sum continues to be a topic of debate among historians.[22][23] Germany was also denied an air force, and the German army was not to exceed 100,000 men.

The text of the Fourteen Points had been widely distributed in Germany as propaganda prior to the end of the war and was well known by the Germans. The differences between this document and the final Treaty of Versailles fueled great anger in Germany.[24] German outrage over reparations and the War Guilt Clause is viewed as a likely contributing factor to the rise of National Socialism. By the time of the Armistice of 11 November 1918, foreign armies had only entered Germany's prewar borders twice: at the Battle of Tannenberg in East Prussia and following the Battle of Mulhouse, the settlement of the French army in the Thann valley. These were both in 1914. This lack of any Allied incursions at the end of the War contributed to the popularization of the stab-in-the-back myth in Germany after the war.

Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize for his peace-making efforts.

Implementation

Ukraine

At the time, Ukrainian delegations failed to receive any support from France and UK. Although some agreements were reached, neither of the states provided any actual support as in general their agenda was to restore Poland and unified anti-Bolshevik Russia.[25] Thus, Ukrainian representatives Arnold Margolin and Teofil Okunevsky had high hopes for American mission, but in the end found it even more categorical than French and British:

This meeting, which took place on June 30, made a tremendous impression on both Okunevsky and me. Lansing showed complete ignorance of the situation and blind faith in Kolchak and Denikin. He categorically insisted that the Ukrainian government recognise Kolchak as the supreme ruler and leader of all anti-Bolshevik armies. When it came to the Wilson principles, the application of which was predetermined in relation to the peoples of the former Austro-Hungarian monarchy, Lansing said that he knew only about the single Russian people and that the only way to restore Russia was a federation modeled on the United States. When I tried to prove to him that the example of the United States testifies to the need for the preliminary existence of separate states as subjects for any possible agreements between them in the future, he evaded answering and began again stubbornly urging us to recognise Kolchak. [...] That's how in reality these principles were implemented. USA supported Kolchak, England – Denikin and Yudenich, France – Galler... Only Petliura was left without any support.

— Arnold Margolin, Ukraine and Policy of the Entente (Notes of Jew and Citizen)

Notes

- ^ Irwin Unger, These United States (2007) 561.

- ^ Hannigan, Robert E. (2016). The Great War and American Foreign Policy, 1914–24. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 125–129. ISBN 9780812248593.

- ^ a b c "Wilson's Fourteen Points, 1918 – 1914–1920 –Milestones – Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 2016-01-02.

- ^ a b Heckscher, p. 470.

- ^ a b c d e "President Woodrow Wilson's 14 Points". www.ourdocuments.gov. Retrieved 2015-12-20.

- ^ Grief, Howard (2008). The Legal Foundation and Borders of Israel Under International Law: A Treatise on Jewish Sovereignty Over the Land of Israel. Mazo Publishers. p. 297. ISBN 9789657344521.

- ^ a b c Godfrey Hodgson, Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand: The Life of Colonel Edward M. House (Yale University Press, 2006), pp. 160–63.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Broich, John. "Why there is no Kurdish nation". The Conversation. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- ^ "Avalon Project – President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points". avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-20.

- ^ (CS) PRECLÍK Vratislav. Masaryk a legie (Масарик и Легии), Ваз. Книга, váz. kniha, 219 str., vydalo nakladatelství Paris Karviná-Mizerov, Žižkova 2379 (734 01 Karviná, CZ) ve spolupráci s Masarykovým demokratickým hnutím (изданная издательством «Пари Карвина», «Зишкова 2379» 734 01 Карвин, в сотрудничестве с демократическим движением Масаpика, Прага), 2019, ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3,

- ^ "Prime Minister Lloyd George on the British War Aims". The World War I Document Archive. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ Grigg 2002, pp. 383–85

- ^ Grigg 2002, p. 384

- ^ Hakim, Joy (2005). War, Peace, and All That Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 16–20. ISBN 0195327233.

- ^ Heckscher, p. 471.

- ^ Heckscher, pp. 479–88.

- ^ Cited in Newer Roosevelt Messages, (ed. Griffith, William, New York: The Current Literature Publishing Company 1919). vol III, p. 1047.

- ^ Cited in Ivo Daalder and James Lindsay, America Unbound: The Bush Revolution in Foreign Policy (Washington: Brookings Institution Press, 2003), p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f Manela, Erez (2006-12-01). "Imagining Woodrow Wilson in Asia: Dreams of East-West Harmony and the Revolt against Empire in 1919". The American Historical Review. 111 (5): 1327–51. doi:10.1086/ahr.111.5.1327. ISSN 1937-5239.

- ^ a b c d Knock, Thomas; Knock, Thomas (2019). To End All Wars (New ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-19192-8.

- ^ Solly, Meilan (October 2, 2020), "What Happened When Woodrow Wilson Came Down With the 1918 Flu?", Smithsonian Magazine, retrieved 2020-12-07

- ^ Markwell, Donald (2006). John Maynard Keynes and International Relations: Economic Paths to War and Peace. Oxford University Press.[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ Hantke, Max; Spoerer, Mark (2010). "The imposed gift of Versailles: the fiscal effects of restricting the size of Germany's armed forces, 1924–9" (PDF). Economic History Review. 63 (4): 849–864. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.2009.00512.x. S2CID 91180171. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-27.

- ^ The Concise Encyclopedia of World History (edited by John Bowle), publisher: Hutchinson of London (Great Portland Street) printed by Taylor, Garnett, Evans & co. in 1958, chapter 20 by John Plamenatz [ISBN missing]

- ^ The Post-Great War Settlement of 1919 and Ukraine

References

- Ferguson, Niall (2006). The War of the World: Twentieth Century Conflict and the Decline of the West. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 1594201005.

- Grigg, John (2002). Lloyd George: War Leader. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9343-X.

- Heckscher, August (1991). Woodrow Wilson. Easton Press. ISBN 0-6841-9312-4.

- MacMillan, Margaret (2001). Paris 1919. Random House. ISBN 0-375-76052-0.

- Snell, John L. (1954). "Wilson on Germany and the Fourteen Points". Journal of Modern History. 26 (4): 364–369. doi:10.1086/237737. JSTOR 1876113.

External links

- Text of Wilson's message to Congress outlining 14 points January 8, 1918

- Text and commentary from ourdocuments.gov

- Interpretation of President Wilson's Fourteen Points Archived 2011-03-07 at the Wayback Machine by Edward M. House

- "President Wilson's Fourteen Points" from the World War I Document Archive

- Wilson's shorthand notes from the Library of Congress

- Arthur Balfour's speech on the Fourteen Points to Parliament, on 27 February 1918 – firstworldwar.com

- Woodrow Wilson Library Wilson's Nobel Peace Prize is digitized. From the Library of Congress