Geddes Plan for Tel Aviv

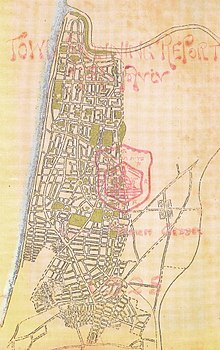

The Geddes plan for Tel Aviv was the proposal of Patrick Geddes presented in 1925. It was the first master plan for the city of Tel Aviv. The Geddes Plan was an extension to the north of the first neighborhoods of the city (now in the southern part adjacent to the Jaffa) reaching to the Yarkon River.

The plan refers to the area known today as the "Old North," where the eastern boundary of the plan is Ibn Gabirol Street and the western boundary is the Mediterranean Sea. Patrick Geddes envisioned public gardens surrounded by residential blocks and small streets, with main roads crossing the city from east to west and south to north.

The choice of Geddes for the Commission of Tel Aviv[edit]

By the time of his commission to plan Tel Aviv, Geddes had corresponded at length with members of the Zionist Commission and had already worked on a number of projects in Palestine[1] including the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in partnership with his son-in-law Frank Mears. Geddes had impressed members of the Zionist Commission with "his total lack of prejudice"[2] and had multiple admirers within the Zionist Commission. His evolutionary concept of cities alongside his "valley section" regional planning, was synergistic with the Zionist Commission's goal of both founding and historically contextualising a modern Hebrew settlement, helping to "re-establish roots in the ancient homeland".[3]

Geddes Vision For Tel Aviv[edit]

Geddes' 62-page plan for Tel Aviv, presented in 1925, linked the existing settlement of Tel Aviv (Ahuzat-Bayit) from Mapu Street (to the southwest) and extended across an area bordered by Borgrashov Street to the southeast, Ibn Gabirol Street to the east, the shoreline to the west and the Yarkon River to the north.[4] Geddes' vision for Tel Aviv was to "realize a conurbation as an example of contemporary planning...based on the valley section and integrated villages, towns and large cities - both old and new."[4] He identified Tel Aviv as "a transitional place and a link between the over-crowded cities of Europe and the renewal of Agricultural Palestine."[5]

Geddes described four street types in his framework for Tel Aviv including "the width of sidewalks, pavements, plantations and lines of building".[6] The largest of these were two major roads running parallel to the shore, beginning near the existing settlement in the south-west and extending to the Yarkon river in the north. These along with three lesser north-south roads were to provide major thoroughfares along the length of the proposed commission.[7] They were then complemented by a series of intersecting "widely spaced, east-west oriented, secondary roads"[8] which helped to channel the cooling sea-breeze off the Mediterranean into the city. Tertiary tree-lined boulevards were added providing green pedestrian promenades, and finally networks of deliberately narrow lanes arranged in an irregular non-aligned 'pinwheel' fashions to discourage non-residential traffic[9] allowed access to the interior of the "superblocks"[7] that much of the land was divided into.

These blocks, set at 560 square metres per lot size, were intended primarily for low density housing which was to be detached or sometimes semi-detached, no more than two stories in height with flat roofs and in double rows around the edges of each block.[10] Housing facing internally was to be accessible via the minor streets running through each block and at the centre of these blocks open space allowing gardens, playgrounds, tennis courts or the enlargement of housing plots[11] were featured. "Geddes rejected the cul-de-sac mode that Mumford advocated" [9] preferring the space in the centre to be open. These planned open spaces were a culmination of lessons learned during his time in India both in form and in economic practicality. Citing medical concerns along with their importance for children,[10] Geddes maintained these open spaces that allowed gardens, playgrounds, or provided for other leisurely pursuits were cheaper to build and maintain than streets.[12] This concept was proposed in an early memorandum. "The model and ideal before us is that of the Garden Village. But this no longer as merely suburban; but as coming into town; and even the very heart of the city block" [13]

Finally, in locating institutional buildings, Geddes plan for Tel Aviv called for "the spatial concentration of cultural institutions"[12] to be located prominently and in close proximity so as to both "prevent their mutual forgetfulness"[14] and to provide cultural expression. Topographically the Habima theatre area was already sited for this purpose but its location at the north-eastern edge prevented it from stitching together the old and new city[15] as a centralised feature. Geddes viewed the old city as the "foundation from which every new city sprang"[16] and considered both Jaffa and Tel Aviv "as parts of the same regional entity".[17] Reflecting on his work in Balrampur, Geddes laid plans for a town square (now Dizengoff Circle) to link the old parts of Tel Aviv and by extension Jaffa to the new development in the north.[18]

Implementation of Geddes Plan[edit]

While "the basic layout of large blocks created by north-south and east-west cross streets that were intersected by narrower access lanes was adhered to",[3] Geddes plan was amended significantly by the time of its official approval in 1938.

The population had almost doubled by 1933[19] and the implementation of the building plots and the alignment of buildings were seen as restrictive by the influx of architects of the Modernist Movement. By 1938 height limitations were loosened, population density allowed to double and proposed open spaces were "often converted into more residential blocks".[20] Land owners were reluctant to relinquish their land for public use and the municipality lacked the funding to purchase it.[20]

Despite the amendments and ongoing debate regarding the legacy of Geddes, areas of Tel Aviv that applied "Geddes principle of freestanding buildings and incremental parcelling of the superblocks prevented the construction of large projects (including housing) and ensured the present day cityscape of detached medium sized buildings surrounded by greenery."[21]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Biger cited by Welter, Volker M. The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes, Israel Studies vol. 14, no. 3. 2009, pp. 97-98.

- ^ Welter, Volker M. The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes, Israel Studies vol. 14, no. 3. 2009, p. 98.

- ^ a b Welter, Volker M. The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes, Israel Studies vol. 14, no. 3. 2009, p. 95.

- ^ a b Welter, Volker M. The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes, Israel Studies vol. 14, no. 3. 2009, p. 100.

- ^ Geddes cited by Welter, Volker M. The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes, Israel Studies vol. 14, no. 3. 2009, p. 106.

- ^ Payton, Neal I. The machine in the garden city: Patrick Geddes' plan for Tel Aviv'. Planning Perspectives vol. 10., Taylor & Francis Online 1995, pp. 368-369. Retrieved 29 March 2013

- ^ a b Payton, Neal I. The machine in the garden city: Patrick Geddes' plan for Tel Aviv'. Planning Perspectives vol. 10., Taylor & Francis Online 1995, p. 365. Retrieved 29 March 2013

- ^ Welter, Volker M. The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes, Israel Studies vol. 14, no. 3. 2009, p. 102.

- ^ a b Payton, Neal I. The machine in the garden city: Patrick Geddes' plan for Tel Aviv'. Planning Perspectives vol. 10., Taylor & Francis Online 1995, p. 366. Retrieved 29 March 2013

- ^ a b Meller, H. Patrick Geddes social evolutionist and city planner,. 1990, p. 280.

- ^ Welter, Volker M. The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes, Israel Studies vol. 14, no. 3. 2009, p. 104.

- ^ a b Welter, Volker M. The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes, Israel Studies vol. 14, no. 3. 2009, p. 106.

- ^ Geddes cited by Welter, Volker M. The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes, Israel Studies vol. 14, no. 3. 2009, p. 104.

- ^ Geddes cited by Meller, H. Patrick Geddes social evolutionist and city planner,. 1990, p. 280.

- ^ Welter, Volker M. The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes, Israel Studies vol. 14, no. 3. 2009, p. 107.

- ^ Welter, Volker M. The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes, Israel Studies vol. 14, no. 3. 2009, p. 110.

- ^ Welter, Volker M. The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes, Israel Studies vol. 14, no. 3. 2009, p. 111.

- ^ Welter, Volker M. The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes, Israel Studies vol. 14, no. 3. 2009, p. 109.

- ^ Payton, Neal I. The machine in the garden city: Patrick Geddes' plan for Tel Aviv'. Planning Perspectives vol. 10., Taylor & Francis Online 1995, p. 373. Retrieved 29 March 2013

- ^ a b Rubin, Noah H. The celebration, condemnation and reinterpretation of the Geddes Plan, 1925: the dynamic planning history of Tel Aviv' Urban History vol. 40 no. 1', Cambridge University Press 2013, p. 124. Retrieved 29 March 2013

- ^ Sandberg, Esther; Tatcher Oren The White City revisited' Progressive Architecture vol. 75 no. 8, 1994, p. 34. Retrieved 29 March 2013