The Hobbit

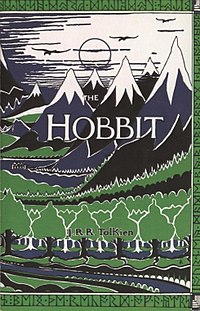

Cover of the 1937 first edition | |

| Author | J. R. R. Tolkien |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Cover artist | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Country | |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Children's literature Fantasy novel |

| Publisher | George Allen & Unwin (UK) |

Publication date | 1937 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback) |

| Pages | 310 pp (first edition) |

| ISBN | n/a Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

| Followed by | The Lord of the Rings |

The Hobbit, or There and Back Again, better known by its abbreviated title The Hobbit, is a fantasy novel and children's book by J. R. R. Tolkien. It was published on 21 September 1937 to wide critical acclaim, being nominated for the Carnegie Medal and awarded a prize from the New York Herald Tribune for best juvenile fiction. The book remains popular and is recognized as a classic in children's literature.

Set in a time "Between the Dawn of Færie and the Dominion of Men",[1] The Hobbit follows the quest of home-loving Bilbo Baggins to win a share of the treasure guarded by the dragon, Smaug. Bilbo's journey takes him from light-hearted, rural surroundings into darker, deeper territory.[2] The story is told in the form of an episodic quest, and most chapters introduce a specific creature, or type of creature, of Tolkien's Wilderland. By accepting the disreputable, romantic, fey and adventurous side of his nature (the "Tookish" side) and applying his wits and common sense, Bilbo develops a new level of maturity, competence and wisdom.[3] The story reaches its climax in the Battle of Five Armies, where many of the characters and creatures from earlier chapters re-emerge to engage in conflict.

Themes of personal growth and forms of heroism figure in the story. Along with conflict, these themes lead critics to cite Tolkien's own experiences, and the those of other writers who fought in World War I, as instrumental in shaping the story. The author's scholarly knowledge of Anglo-Saxon literature and interest in fairy tales are also often noted as influences.

Due to the book's critical and financial success, Tolkien's publishers requested a sequel. As work on The Lord of the Rings progressed, Tolkien made retrospective accommodations for it in one chapter of The Hobbit. These few but significant changes were integrated into the second edition. Further editions followed with minor emendations, including those reflecting Tolkien's changing concept of the world into which Bilbo stumbled.

The work has never been out of print since the paper shortages of the Second World War. Its ongoing legacy encompasses many adaptations for stage, screen, radio, and gaming, both board and video games. Some of these adaptations have received critical recognition of their own, including a video game that won the Golden Joystick Award, a scenario of a war game that won an Origins Award, and an animated picture nominated for a Hugo Award.

Characters

- Bilbo Baggins, the titular protagonist, a respectable, conservative hobbit. During his adventure, Bilbo often refers to the contents of his larder at home and wishes he had more food. Until he finds the magic ring, he is more baggage than help.

- Gandalf, an itinerant wizard who introduces Bilbo to a company of thirteen dwarves. During the journey he disappears on side errands dimly hinted at, only to appear again at key moments in the story.

- Thorin Oakenshield, proud, pompous head of the company of dwarves and heir to a dwarven kingdom under the Lonely Mountain. Thorin makes many mistakes in his leadership, relying on Gandalf or Bilbo to get him out of trouble, but he proves himself a mighty warrior.

- Smaug, a dragon who long ago pillaged the dwarven kingdom of Thorin's grandfather and sleeps upon the vast treasure.

The plot involves a host of other characters of varying importance, such as the twelve other dwarves of the company; two types of elves: both puckish and more serious warrior types[4]; men (humans); man-eating trolls; evil cave-dwelling goblins; forest-dwelling giant spiders who can speak; immense and heroic eagles who also speak; evil wolves, or Wargs, who are allied with the goblins; Elrond the sage; Gollum, a strange creature inhabiting an underground lake; Beorn, a man who can assume bear form; and Bard the Bowman, a grim but honourable archer of Lake-town.[5]

Plot

Gandalf tricks Bilbo into hosting a party for Thorin's band of dwarves, who sing of reclaiming the Lonely Mountain and its vast treasure from the dragon Smaug. When the music ends, Gandalf unveils a map showing a secret door into the Mountain and proposes that the dumbfounded Bilbo serve as the expedition's "burglar". The dwarves ridicule the idea, but Bilbo, indignant, joins despite himself.

The group travel into the wild, where Gandalf saves the company from trolls and leads them to Rivendell, where Elrond reveals more secrets from the map. Passing over the Misty Mountains, they are caught by goblins and driven deep underground. Although Gandalf rescues them, Bilbo gets separated from the others as they flee the goblins. Lost in the goblin tunnels, he stumbles across a mysterious ring and then encounters Gollum, who engages him in a game of riddles with deadly stakes. With the help of the ring, which confers invisibility, Bilbo escapes and rejoins the dwarves, raising his reputation with them. The goblins and Wargs give chase but the company are saved by eagles before resting in the house of Beorn.

The company enter the black forest of Mirkwood without Gandalf. In Mirkwood, Bilbo first saves the dwarves from giant spiders and then from the dungeons of the Wood-elves. Nearing the Lonely Mountain, the travellers are welcomed by the human inhabitants of Lake-town, who hope the dwarves will fulfil prophecies of Smaug's demise. The expedition travel to the Mountain and find the secret door; Bilbo scouts the dragon's lair, stealing a great cup and learning of a weakness in Smaug's armour. The enraged dragon, deducing that Lake-town has aided the intruder, sets out to destroy the town. A noble thrush who overheard Bilbo's report of Smaug's vulnerability reports it to Bard, who slays the Dragon.

When the dwarves take possession of the mountain, Bilbo finds the Arkenstone, an heirloom of Thorin's dynasty, and steals it. The Wood-elves and Lake-men besiege the Mountain and request compensation for their aid, reparations for Lake-town's destruction, and settlement of old claims on the treasure. Thorin refuses and, having summoned his kin from the mountains of the North, reinforces his position. Bilbo tries to ransom the Arkenstone to head off a war, but Thorin is intransigent. He banishes Bilbo, and battle seems inevitable.

Gandalf reappears to warn all of an approaching army of goblins and Wargs. The dwarves, men, and elves band together, but only with the timely arrival of the eagles and Beorn do they win the climactic Battle of Five Armies. Thorin, on his deathbed from wounds, reconciles with Bilbo. The treasure is divided, but, having little desire for it, Bilbo refuses most of his share. Nevertheless, he returns home wealthy.

Concept and creation

Background

In the early 1930s Tolkien was pursuing an academic career at Oxford as Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon, with a fellowship at Pembroke College. He had had two poems published in small collections: Goblin Feet[6] and The Cat and the Fiddle: A Nursery Rhyme Undone and its Scandalous Secret Unlocked,[7] a reworking of the nursery rhyme Hey Diddle Diddle. His creative endeavours at this time also included letters from Father Christmas to his children – illustrated manuscripts that featured warring gnomes and goblins, and a helpful polar bear – alongside the development of elven languages and an attendant mythology, which he had been developing since 1917. These works all saw posthumous publication.[8]

In a 1955 letter to W. H. Auden, Tolkien recollects that he began work on The Hobbit one day early in the 1930s, when he was marking School Certificate papers. He found a blank page. Suddenly inspired, he wrote the words, "In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit." By late 1932 he had finished the story and then lent the manuscript to several friends, including C. S. Lewis[9] and a student of Tolkien's named Elaine Griffiths.[10] In 1936, when Griffiths was visited in Oxford by Susan Dagnall, a staff member of the publisher George Allen & Unwin, she is reported to have either lent Dagnall the book[10] or suggested she borrow it from Tolkien.[11] In any event, Miss Dagnall was impressed by it, and showed the book to Stanley Unwin, who then asked his 10-year-old son Rayner to prepare a review of it. After Rayner wrote a short piece about Tolkien's manuscript, it was published by Allen & Unwin.[12]

Publication

George Allen & Unwin, Ltd. of London published the first edition of The Hobbit on 21 September 1937. The original printing numbered 1,500 copies and sold out by December due to enthusiastic reviews.[13] This first printing was illustrated with many black-and-white drawings by Tolkien, who also designed the dust jacket. Houghton Mifflin of Boston and New York reset type for an American edition, to be released early in 1938, in which four of the illustrations would be colour plates. Allen & Unwin decided to incorporate the colour illustrations into their second printing, released at the end of 1937.[14] Despite the book's popularity, paper rationing brought on by wartime conditions and not ending until 1949 meant that the book was often unavailable in this period.[15]

Subsequent editions in English were published in 1951, 1966, 1978 and 1995. The novel has been reprinted frequently by many publishers.[16] In addition, The Hobbit has been translated into over forty languages, some of them more than once.[17]

Revisions

In December 1937, The Hobbit's publisher, Stanley Unwin, asked Tolkien for a sequel. In response Tolkien provided drafts for The Silmarillion, but the editors rejected them, believing that the public wanted "more about hobbits".[18] Tolkien subsequently began work on 'The New Hobbit', which would eventually become The Lord of the Rings,[18] a course that would not only change the context of the original story, but also lead to substantial changes to the character of Gollum.

In the first edition of The Hobbit, Gollum willingly bets his magic ring on the outcome of the riddle-game, and he and Bilbo part amicably.[4] In the second edition edits, in order to reflect the new concept of the ring and its corrupting abilities, Tolkien made Gollum more aggressive towards Bilbo and distraught at losing the ring. The encounter ends with Gollum's curse, "Thief! Thief, Baggins! We hates it, we hates it, we hates it forever!" This sets the stage for Gollum's portrayal in The Lord of the Rings.

Tolkien sent this revised version of the chapter "Riddles in the Dark" to Unwin as an example of the kinds of changes needed to bring the book into conformance with The Lord of the Rings, but he heard nothing back for years. When he was sent galley proofs of a new edition, Tolkien was surprised to find the sample text had been incorporated.[19] In The Lord of the Rings, the original version of the riddle game is explained as a "lie" made up by Bilbo, whereas the revised version contains the "true" account.[20] The revised text became the second edition, published in 1951 in both the UK and the USA.[21]

After an unauthorized paperback edition of The Lord of the Rings appeared from Ace Books in 1965, Houghton Mifflin and Ballantine requested Tolkien to refresh the text of The Hobbit in order to renew US copyright.[22] This text became the 1966 third edition. Tolkien took the opportunity to align the narrative even more closely to The Lord of the Rings and to cosmological developments from his still unpublished Quenta Silmarillion as it stood at that time.[23] These small edits included, for example, changing the phrase elves that are now called Gnomes from the first[24] and second[25] editions on page 63, to High Elves of the West, my kin in the third edition.[26] Tolkien had used "gnome" in his earlier writing to refer to the second kindred of the High Elves—the Noldor (or "Deep Elves")—thinking "gnome", derived from the Greek gnosis (knowledge), was a good name for the wisest of the elves. However, because of its common denotation of a garden gnome, derived from the 16th Century Paracelsus, Tolkien abandoned the term.[27]

In order to fit the tone of The Hobbit better to its sequel, Tolkien began a new version in 1960, removing the narrative asides. He abandoned the new revision at chapter three after he received criticism that it "just wasn't The Hobbit", implying it had lost much of its light-hearted tone and quick pace.[28]

Posthumous editions

Since the author's death, two editions of The Hobbit have been published with commentary on the creation, emendation and development of the text.

In The Annotated Hobbit Douglas Anderson provides the entire text of the published book, alongside commentary and illustrations. Anderson's commentary shows many of the sources Tolkien brought together in preparing the text, and chronicles in detail the changes Tolkien made to the various published editions. Alongside the annotations, the text is illustrated by pictures from many of the translated editions, including images by Tove Jansson.[29] Also printed here are a number of hard to find texts such as the 1923 version of Tolkien's poem "Iumonna Gold Galdre Bewunden". Micheal D. C. Drout and Hilary Wynn comment the work provides a solid foundation for further criticism.[30]

With The History of the Hobbit, published in two parts in 2007, John Rateliff provides the full text of the earliest and intermediary drafts of the book, alongside commentary that shows relationships to Tolkien's scholarly and creative works, both contemporary and later. Rateliff also provides the abandoned 1960s retelling. The book keeps Rateliff's commentary separate from Tolkien's text, allowing the reader to read the original draft as a story. Rateliff also provides previously unpublished illustrations by Tolkien. Jason Fisher, published in Mythlore, states in his review that the work is "an indispensable new starting point for the study of The Hobbit."[31]

Illustration and design

Tolkien's correspondence and publisher's records show that Tolkien was involved in the design and illustration of the entire book. All elements were the subject of considerable correspondence and fussing over by Tolkien. Rayner Unwin, in his publishing memoir, comments:[32]

In 1937 alone Tolkien wrote 26 letters to George Allen & Unwin... detailed, fluent, often pungent, but infinitely polite and exasperatingly precise... I doubt any author today, however famous, would get such scrupulous attention.

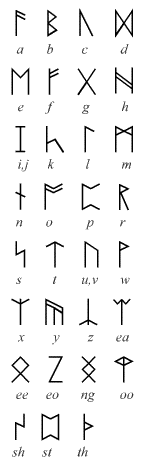

Even the maps, of which Tolkien originally proposed five, were considered and debated. He wished Thror's map to be tipped in (that is, glued in after the book has been bound) at first mention in the text, and with the moon-letters (Anglo-Saxon runes) on the reverse so they could be seen when held up to the light.[15] In the end the cost, as well as the shading of the maps, which would be difficult to reproduce, resulted in the final design of two maps as endpapers, Thror's map, and the Map of the Wilderland, both printed in black and red on the paper's cream background.[34]

Originally Allen & Unwin planned to illustrate the book only with the endpaper maps, but Tolkien's first tendered sketches so charmed the publisher's staff that they opted to include them without raising the book's price despite the extra cost. Thus encouraged, Tolkien supplied a second batch of illustrations. The publisher accepted all of these as well, giving the first edition ten black-and-white illustrations plus the two endpaper maps. The illustrated scenes were: The Hill: Hobbiton across the Water, The Trolls, The Mountain Path, The Misty Mountains looking West from the Eyrie towards Goblin Gate, Beorn's Hall, Mirkwood, The Elvenking's Gate, Lake Town, and the Front Gate. All but one of the illustrations were a full page, and one, the Mirkwood illustration, required a separate plate.[35]

Satisfied with his skills, the publishers thence asked Tolkien to design a dust jacket. This project, too, became the subject of many iterations and much correspondence, with Tolkien always writing disparagingly of his own ability to draw. The runic inscription around the edges of the illustration are a phonetic transliteration of English, giving the title of the book and details of the author and publisher.[36] The original jacket design contained several shades of several colours, but Tolkien redrew it several times using fewer colours each time. His final design consisted of four colours. The publishers, mindful of the cost, removed the red from the sun to end up with only black, blue, and green ink on white stock.[37]

The publisher's production staff designed a binding, but Tolkien objected to several elements. Through several iterations, the final design ended up as mostly the author's. The spine shows Anglo Saxon runes: two "þ" (Thráin and Thrór) and one "D" (Door). The front and back covers were mirror images of each other, with an elongated dragon characteristic of Tolkien's style stamped along the lower edge, and with a sketch of the Misty Mountains stamped along the upper edge.[38]

Once illustrations were approved for the book, Tolkien proposed colour plates as well. The publisher would not relent on this, so Tolkien pinned his hopes on the American edition to be published about six months later. Houghton Mifflin rewarded these hopes with the replacement of the frontispiece (The Hill: Hobbiton-across-the Water) in colour and the addition of new colour plates: Rivendell, Bilbo Woke Up with the Early Sun in His Eyes, Bilbo comes to the Huts of the Raft-elves and a Conversation with Smaug, which features a dwarvish curse written in Tolkien's invented script Tengwar, and signed with two "þ, "Th" runes.[39] The additional illustrations proved so appealing that George Allen & Unwin adopted the colour plates as well for their second printing, with exception of Bilbo Woke Up with the Early Sun in His Eyes).[38]

Different editions have been illustrated in diverse ways. Many follow the original scheme at least loosely, but many others are illustrated by other artists, especially the many translated editions. Some cheaper editions, particularly paperback, are not illustrated except with the maps. "The Children's Book Club" edition of 1942 includes the black-and-white pictures but no maps, an anomaly.[40]

Tolkien's use of runes, both as decorative devices and as magical signs within the story, has been cited as a major cause for the popularisation of runes within "New Age" and esoteric literature,[41] stemming from Tolkien's popularity with the elements of counter-culture in the 1970s.[42]

Genre

The Hobbit takes cues from narrative models of children's literature, as shown by its omniscient narrator and characters that pre-adolescent children can identify with, such as the small, food-obsessed, and morally ambiguous Bilbo. The text emphasizes the relationship between time and narrative progress and it openly distinguishes "safe" from "dangerous" in its geography. Both are key elements of works intended for children,[43] as is the "home-away-home" (or there and back again) plot structure typical of the Bildungsroman.[44] While Tolkien claimed later to dislike the aspect of the narrative voice addressing the reader directly,[45] the narrative voice contributes significantly to the success of the novel, and the story is, therefore, often read aloud.[46] Emer O'Sullivan, in her Comparative Children's Literature, notes The Hobbit as one of a handful of children's books that is accepted into mainstream literature, alongside Jostein Gaarder's Sophie's World (1991) and J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter series (1997–2007).[47]

Tolkien intended The Hobbit as a fairy story and wrote it in a tone suited to addressing children.[48] Many of the initial reviews refer to the work as a fairy story. However, Bilbo Baggins is not the usual fairy tale protagonist – not the handsome eldest son or beautiful youngest daughter – but a plump, middle-aged, well-to-do Hobbit.[49] The work is much longer than Tolkien's ideal proposed in his essay On Fairy Stories. Many fairy tale motifs, such as the repetition of similar events seen in the dwarves' arrival at Bilbo's and Beorn's homes, and folklore themes, such as trolls turning to stone, are to be found in the story.[50] The Hobbit conforms to Vladimir Propp's 31-motif model of folktales presented in his 1928 work Morphology of the Folk Tale, based on a structuralist analysis of Russian folklore.[51]

The book is popularly called (and often marketed as) a fantasy novel, but like Peter Pan and Wendy by J. M. Barrie and The Princess and the Goblin by George MacDonald, both of which influenced Tolkien and contain fantasy elements, it is primarily identified as being children's literature. The two genres are not mutually exclusive, so some definitions of high fantasy include works for children by authors such as L. Frank Baum and Lloyd Alexander alongside the works of Gene Wolfe and Jonathan Swift, which are more often considered adult literature. Sullivan credits the first publication of The Hobbit as an important step in the development of high fantasy, and further credits the 1960s paperback debuts of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings as essential to the creation of a mass market for fiction of this kind as well the fantasy genre's current status.[52]

Style

Tolkien's prose is unpretentious and straightforward, taking as given the existence of his imaginary world and describing its details in a matter-of-fact way, while often introducing the new and fantastic in an almost casual manner. This down-to-earth style, also found in later fantasy such as Richard Adams' Watership Down and Peter Beagle's The Last Unicorn, accepts readers into the fictional world, rather than cajoling or attempting to convince them of its reality.[53] While The Hobbit is written in a simple, friendly language, each of its characters has a unique voice. The narrator, who occasionally interrupts the narrative flow with asides (a device common to both children's and Anglo-Saxon literature),[52] has his own linguistic style separate from those of the main characters.[54]

The basic form of the story is that of a quest,[55] told in episodes. For the most part of the book, each chapter introduces a different denizen of the Wilderland, some friendly towards the protagonists, and some threatening. While many of the encounters are dangerous or threatening, the general tone is light-hearted, and interspersed with songs. One example of the use of song to maintain tone is when Thorin and Company are kidnapped by goblins, who, when marching them into the underworld, sing:

Clap! Snap! the black crack!

Grip, grab! Pinch, nab!

And down down to Goblin-town

You go, my lad!

This onomatopœic singing undercuts the dangerous scene with a sense of humour. Tolkien achieves balance of humour and danger through other means as well, as seen in the foolishness and Cockney dialect of the trolls and in the drunkenness of the elven captors.[56] The general form—that of a journey into strange lands, told in a light-hearted mood and interspersed with songs—may be following the model of The Icelandic Journals by Tolkien's literary idol William Morris.[57]

The novel draws on Tolkien's knowledge of historical languages and early Northern European texts. The names of Gandalf and all but one of the thirteen dwarves were taken directly from the Old Norse poem Völuspá from the Poetic Edda.[58] Several of the author's illustrations (including the dwarven map, the frontispiece and the dust jacket) make use of Anglo-Saxon runes. The names of the dwarf-friendly ravens are also derived from the Old Norse for raven and rook,[31] but their characters are unlike the typical war-carrion from Old Norse and Anglo-Saxon literature.[50] Tolkien, however, is not simply skimming historical sources for effect: linguistic styles, especially the relationship between the modern and ancient, has been seen to be one of the major themes explored by the story.[59]

Critical analysis

Themes

The development and maturation of the protagonist, Bilbo Baggins, is central to the story. This journey of maturation, where Bilbo gains a clear sense of identity and confidence in the outside world, may be seen as a Bildungsroman rather than a traditional quest.[60] The Jungian concept of individuation is also reflected through this theme of growing maturity and capability, with the author contrasting Bilbo's personal growth against the arrested development of the dwarves.[3] The analogue of the "underworld" and the hero returning from it with a boon (such as the ring, or Elvish blades) that benefits his society is seen to fit the mythic archetypes regarding initiation and male coming-of-age as described by Joseph Campbell.[56] Jane Chance compares the development and growth of Bilbo against other characters to the concepts of just Kingship versus sinful kingship derived from the Ancrene Wisse (which Tolkien had written on in 1929) and a Christian understanding of Beowulf.[61]

The overcoming of greed and selfishness has been seen as the central moral of the story.[62] Whilst greed is a recurring theme in the novel, with many of the episodes stemming from one or more of the characters' simple desire for food (be it trolls eating dwarves or dwarves eating Wood-elf fare) or a desire for beautiful objects, such as gold and jewels,[63] it is only by the Arkenstone's influence upon Thorin that greed, and its attendant vices "coveting" and "malignancy", come fully to the fore in the story and provide the moral crux of the tale. Bilbo steals the Arkenstone—a most ancient relic of the dwarves—and attempts to ransom it to Thorin for peace. However, Thorin turns on the Hobbit as a traitor, disregarding all the promises and "at your services" he had previously bestowed.[64] In the end Bilbo gives up the precious stone and most of his share of the treasure in order to help those in greater need. Tolkien also explores the motif of jewels that inspire intense greed which corrupts those that covet them in the Silmarillion, and there are connections between the words "Arkenstone" and "Silmaril" in Tolkien's invented etymologies.[65]

The Hobbit employs themes of animism. An important concept in anthropology and child development, animism is the idea that all things—including inanimate objects and natural events, such as storms or purses, as well as living things like animals and plants—possess human-like intelligence. John D. Rateliff calls this the "Doctor Dolittle Theme" in The History of the Hobbit, and cites the multitude of talking animals as indicative of this theme. These talking creatures include ravens, spiders and the dragon Smaug, alongside the anthropomorphic goblins and elves. Patrick Curry notes that animism is also found in Tolkien's other works, and mentions the "roots of mountains" and "feet of trees" in The Hobbit as a linguistic shifting in level from the inanimate to animate.[66] Tolkien saw the idea of animism as closely linked to the emergence of human language and myth: "...The first men to talk of 'trees and stars' saw things very differently. To them, the world was alive with mythological beings... To them the whole of creation was "myth-woven and elf-patterned".'[67]

Interpretation

The Hobbit can be seen as a creative exposition of Tolkien's theoretical and academic work. Themes found in early English literature, and specifically in the poem Beowulf, have a heavy presence in defining the ancient world Bilbo stepped into. Tolkien, an accomplished Beowulf scholar, claims the poem to be among his “most valued sources” in writing The Hobbit.[68] Tolkien is credited with being the first critic to expound on Beowulf as a literary work with value beyond merely historical, and his 1936 lecture Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics is still required reading for students of Anglo-Saxon. The Beowulf poem contains several elements that Tolkien borrowed for The Hobbit, including a monstrous, intelligent dragon[69]. Certain descriptions in The Hobbit seem to have been lifted straight out of Beowulf with some minor rewording, such as when each dragon stretches out its neck to sniff for intruders.[70] Likewise, Tolkien’s descriptions of the lair as accessed through a secret passage mirror those in Beowulf. Tolkien refines parts of Beowulf’s plot that he appears to have found less than satisfactorily described, such as details about the cup-thief and the dragon’s intellect and personality.[71]

Another influence from the Anglo-Saxon is the appearance named blades of renown, adorned in runes. It is in the use of his elf-blade that we see Bilbo finally taking his first independent heroic action. By his naming the blade "Sting" we also see Bilbo's acceptance of the kinds of cultural and linguistic practices found in Beowulf, signifying his entrance into the ancient world in which he found himself.[72] This progression culminates in Bilbo stealing a cup from the dragon's hoard, rousing him to wrath—an incident directly mirroring Beowulf, and an action entirely determined by traditional narrative patterns. As Tolkien wrote, "...The episode of the theft arose naturally (and almost inevitably) from the circumstances. It is difficult to think of any other way of conducting the story at this point. I fancy the author of Beowulf would say much the same."[68]

As in plot and setting, Tolkien brings his literary theories to bear in forming characters and their interactions. He portrays Bilbo as a modern anachronism exploring an essentially antique world. Bilbo is able to negotiate and interact within this antique world because language and tradition make connections between the two worlds. For example, Gollum's riddles are taken from old historical sources, while those of Bilbo come from modern nursery books. It is the form of the riddle game, familiar to both, which allows Gollum and Bilbo to engage each other, rather than the content of the riddles themselves. This idea of a superficial contrast between characters' individual linguistic style, tone and sphere of interest, leading to an understanding of the deeper unity between the ancient and modern, is a recurring theme in The Hobbit.[59]

Smaug is the main antagonist. In many ways the Smaug episode reflects and references the dragon of Beowulf, and Tolkien uses the episode to put into practice some of the ground-breaking literary theories he had developed about the Anglo-Saxon poem and its portrayal of the dragon as having bestial intelligence rather than being of purely symbolic value.[69] Smaug the dragon and his golden hoard may be seen as a symbol of the traditional relationship between evil and metallurgy as collated in the depiction of Pandæmonium with its "Belched fire and rolling smoke" in Milton's Paradise Lost.[73] Of all the characters, Smaug's speech is the most modern, using idioms such as "Don't let your imagination run away with you!"

Just as Tolkien's literary theories have been seen to influence the tale, so have Tolkien's experiences. The Hobbit may be read as Tolkien's parable of World War I, where the hero is plucked from his rural home and thrown into a far-off war where traditional types of heroism are shown to be futile.[74] The tale as such explores the theme of heroism. As Jane Croft notes, Tolkien's literary reaction to war at this time differed from most post-war writers by eschewing irony as a method for distancing events and instead using mythology to mediate his experiences.[75] Similarities to the works of other writers who faced the Great War are seen in The Hobbit, including portraying warfare as anti-pastoral: in "The Desolation of Smaug", both the area under the influence of Smaug before his demise and the setting for The Battle of the Five Armies later are described as barren, damaged landscapes.[76] The Hobbit makes a warning against repeating the tragedies of World War I,[77] and Tolkien's attitude as a veteran may well be summed up by Bilbo's comment:[75]

Victory after all, I suppose! Well, it seems a very gloomy business.

Reception

On first publication in October 1937, The Hobbit was met with almost unanimously favourable reviews from publications both in the UK and the USA, including The Times, Catholic World and The New York Post. C. S. Lewis, friend of Tolkien (and later author of The Chronicles of Narnia between 1949–1964), writing in The Times reports:

The truth is that in this book a number of good things, never before united, have come together; a fund of humour, an understanding of children, and a happy fusion of the scholar's with the poet's grasp of mythology... The professor has the air of inventing nothing. He has studied trolls and dragons at first hand and describes them with that fidelity that is worth oceans of glib "originality."

Lewis also compares the book to Alice in Wonderland in that both children and adults may find different things to enjoy in it, and places it alongside Flatland, Phantastes, and The Wind in the Willows.[78] W. H. Auden, in his review of the sequel The Fellowship of the Ring calls The Hobbit "one of the best children's stories of this century".[79] Auden was later to correspond with Tolkien, and they became friends. The Hobbit was nominated for the Carnegie Medal and awarded a prize from the New York Herald Tribune for best juvenile fiction of the year (1938). More recently, the book has been recognized as "Most Important 20th-Century Novel (for Older Readers)" in the Children's Books of the Century poll in Books for Keeps.[80]

Publication of the sequel The Lord of the Rings altered many critics' reception of the work. Instead of approaching The Hobbit as a children's book in its own right, critics such as Randell Helms picked up on the idea of The Hobbit as being a "prelude", relegating the story to a dry-run for the later work. Countering a presentist interpretation are those who say this approach misses out on much of the original's value as a children's book and as a work of high fantasy in its own right, and that it disregards the book's influence on these genres.[52] Commentators such as Paul Kocher,[81] John D. Rateliff[82] and C. W. Sullivan[52] encourage readers to treat the works separately, both because The Hobbit was conceived, published, and received independently of the later work, and also in order to prevent the reader from having false expectations of tone and style dashed.

Legacy

The Lord of the Rings

While The Hobbit has been adapted and elaborated upon in many ways, its sequel The Lord of the Rings is often claimed to be its greatest legacy. The plots share the same basic structure progressing in the same sequence: the stories begin at Bag End, the home of Bilbo Baggins; Gandalf sends the protagonist into a quest eastward; Elrond offers a haven and advice; the adventurers escape dangerous creatures underground (Goblin Town/Moria); they engage another group of elves (The Elf King's realm/Lothlórien); they traverse a desolate region (Desolation of Smaug/the Dead Marshes); they fight in a massive battle; a descendant of kings is restored to his ancestral throne (Bard/Aragorn); and the questing party returns home to find it in a deteriorated condition (having possessions auctioned off/the scouring of the Shire).[83]

The Lord of the Rings contains several more supporting scenes, and has a more sophisticated plot structure, following the paths of multiple characters. Tolkien wrote the later story in much less humorous tones and infused it with more complex moral and philosophical themes. The differences between the two stories can cause difficulties when readers, expecting them to be similar, find that they are not.[83] Many of the thematic and stylistic differences arose because Tolkien wrote The Hobbit as a story for children, and The Lord of the Rings for the same audience, who had subsequently grown up since its publication. Some differences are in minor details; for example, goblins are more often referred to as Orcs in The Lord of the Rings. Further, Tolkien's concept of Middle-earth was to continually change and slowly evolve throughout his life and writings.[84]

The Hobbit in education

The style and themes of the book have been seen to help stretch precocious young readers' literacy skills, preparing them to approach the works of Dickens and Shakespeare. By contrast, offering readers modern teenage-oriented fiction may not exercise their advanced reading skills, while the material may contain themes more suited to adolescents.[85] As one of several books that has been recommended for 11–14 year old boys to encourage literacy in that demographic, The Hobbit is promoted as "the original and still the best fantasy ever written."[86]

Several teaching guides and books of study notes have been published to help teachers and students gain the most from the book. The Hobbit introduces literary concepts, notably allegory, to young readers, as the work has been seen to have allegorical aspects reflecting the life and times of the author.[76] Meanwhile the author himself rejected an allegorical reading of his work.[87] This tension can help introduce readers to 'readerly' and 'writerly' interpretations, to tenets of New Criticism, and critical tools from Freudian analysis, such as sublimation, in approaching literary works.[88]

Another approach to critique taken in the classroom has been to propose the insignificance of female characters in the story as sexist. While Bilbo may be seen as a literary symbol of 'small folk' of any gender,[89] a gender-conscious approach can help students establish notions of a "socially symbolic text" where meaning is generated by tendentious readings of a given text.[90] Ironically, by this interpretation, the first authorized adaptation was a stage production in a girls' school.[16]

Adaptations

In 1969 (over 30 years after first publication), Tolkien sold the film and merchandising rights to The Hobbit to United Artists under an agreement stipulating a lump sum payment of £10,000[91] plus a 7.5% royalty after costs, payable to Allen & Unwin and the author.[92] In 1976 (three years after the author's death) United Artists sold the rights to Saul Zaentz Company, who trade as Tolkien Enterprises. Since then all "authorized" adaptations have been signed-off by Tolkien Enterprises. In 1997 Tolkien Enterprises licensed the film rights to Miramax, which assigned them in 1998 to New Line Cinema.[93] The heirs of Tolkien, including his son Christopher Tolkien, filed suit against New Line Cinema in February 2008 seeking payment of profits and to be "entitled to cancel... all future rights of New Line... to produce, distribute, and/or exploit future films based upon the Trilogy and/or the Films... and/or... films based on The Hobbit."[94][95]

The first authorized adaptation of The Hobbit appeared in March 1953, a stage production by St. Margaret's School, Edinburgh.[16] The Hobbit has since been adapted for other media many times.

The BBC Radio 4 series The Hobbit radio drama was an adaptation by Michael Kilgarriff, broadcast in eight parts (four total hours) from September to November 1968. It starred Anthony Jackson as narrator, Paul Daneman as Bilbo and Heron Carvic as Gandalf. The series was released on audio cassette in 1988 and on CD in 1997.[96]

The Hobbit, an animated version of the story produced by Rankin/Bass, debuted as a television movie in the United States in 1977. In 1978, Romeo Muller won a Peabody Award for his teleplay for The Hobbit. The film was also nominated for the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation, but lost to Star Wars. The adaptation has been called "excruciable"[17] and confusing for those not already familiar with the plot.[97] A live-action film version is planned to be co-produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and New Line Cinema, produced by Peter Jackson[98]

ME Games Ltd (formerly Middle-earth Play-by-Mail), which has won several Origin Awards, uses the Battle of Five Armies as an introductory scenario to the full game and includes characters and armies from the book.[99]

Several computer and video games, both licensed and unlicensed, have been based on the story. One of the most successful was The Hobbit, an award-winning computer game developed in 1982 by Beam Software and published by Melbourne House with compatibility for most computers available at the time. A copy of the novel was included in each game package in order to encourage players to engage the text, since ideas for gameplay could be found therein.[100] Likewise, it can be seen that the game is not attempting to re-tell the story, but rather sits along-side it, using the narrative to both structure and motivate gameplay.[101] The game won the Golden Joystick Award for Strategy Game of the Year in 1983[102] and was responsible for popularizing the phrase, "Thorin sits down and starts singing about gold."[103]

Collectors' market

While reliable figures are difficult to obtain, estimated global sales of The Hobbit run between 35[66] and 100[104] million copies since 1937. In the UK The Hobbit has not retreated from the top 5,000 books of Nielsen BookScan since 1995, when the index began, achieving a three-year sales peak rising from 33,084 (2000) to 142,541 (2001), 126,771 (2002) and 61,229 (2003), ranking it at the 3rd position in Nielsens' "Evergreen" book list.[105] The enduring popularity of The Hobbit makes early printings of the book attractive collectors' items. The first printing of the first English-language edition can sell for between £6,000 and £20,000 at auction,[106][107] although the price for a signed first edition has reached over £60,000.[104]

See also

- English-language editions of The Hobbit

- Early American editions of The Hobbit

- Translations of The Hobbit

- "The Quest of Erebor", Tolkien's retconned backstory for the novel published in Unfinished Tales

Notes

- ^ Eaton, Anne T. (13 March 1938). "A Delightfully Imaginative Journey". The New York Times.

- ^ Langford, David (2001). "Lord of the Royalties". SFX magazine. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- ^ a b Matthews, Dorothy (1975). "The Psychological Journey of Bilbo Baggins". A Tolkien Compass. Open Court Publishing. pp. 27–40. ISBN 9780875483030.

- ^ a b Anderson 2003, p. 120

- ^ Sparknotes 101 Literature. Spark Educational Publishing. 2004. pp. 366–367. ISBN 1411400267. [1]

- ^ Oxford Poetry (1915) Blackwells

- ^ Yorkshire Poetry, Leeds, vol. 2, no. 19, October-November 1923

- ^ Rateliff 2007, pp. xxx–xxxi

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 181

- ^ a b Carpenter 1981, p. 294

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 184

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 192

- ^ Hammond 1993, p. 8

- ^ Hammond 1993, pp. 18–23

- ^ a b Anderson 2003, p. 22

- ^ a b c Anderson 2003, pp. 384–386

- ^ a b Anderson 2003, p. 23

- ^ a b Carpenter 1977, p. 195

- ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 215

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Prologue. OCLC 9552942.

- ^ Anderson 2003, pp. 18–23

- ^ Rateliff 2007, p. 765

- ^ Anderson 2003, p. 218

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937). The Hobbit. London: George Allen & Unwin. p. 63.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1951). The Hobbit. London: George Allen & Unwin. p. 63.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1966). The Hobbit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 62. ISBN 0-395-07122-4.

- ^ Tolkien, Christopher (1983). The History of Middle-earth: Vol 1 "The Book of Lost Tales 1". George Allen & Unwin. pp. 43–44. ISBN 0048232386.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Rateliff 2007, p. 781

- ^ An example, alongside other illustrations can be seen at: Houghton Mifflin

- ^ Drout, Michael D. C. (2006). "Review Essay: Tom Shippey's J. R. R. Tolkien: Author of the Century and a Look Back at Tolkien Criticism since 1982". Envoi. Retrieved 19 June 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Fisher, Jason (2008). "The History of the Hobbit (review)". Mythlore (101/102).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Anderson 2003, p. 14

- ^ Anderson 2003, pp. 378–379

- ^ Hammond 1993, p. 18

- ^ Hammond 1993, p. 21

- ^ Flieger, Verlyn (2005). Interrupted Music: The Making of Tolkien's Mythology. Kent State University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0873388240.

- ^ Hammond 1993, p. 48

- ^ a b Hammond 1993, p. 54

- ^ Rateliff 2007, p. 602

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1942). The Hobbit. London: The Children's Book Club.

- ^ Elliot, Ralph W. V. (1998). ""Runes in English Literature" From Cynewulf to Tolkien"". In Klaus Duwel (ed.). Runeninschriften Als Quelle Interdisziplinarer Forschung. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 663–664. ISBN 3110154552.

- ^ Plowright, Sweyn (2006). The Rune Primer: A Down-to-Earth Guide to the Runes. Rune-Net Press. p. 137. ISBN 0958043515.

- ^

Poveda, Jaume Alberdo (2003–2004). "Narrative Models in Tolkien's Stories of Middle Earth" (pdf). Journal of English Studies. 4: 7–22. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Gamble, Nikki (2002). Exploring Children's Literature: Teaching the Language and Reading of Fiction. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=96t8LdsoVX4C: Sage. p. 43. ISBN 0761940464.

{{cite book}}: External link in|location=|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Carpenter 1977, p. 193

- ^ "The Hobbit Major Themes". Cliff Notes The Hobbit. Cliff Notes. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^ O'Sullivan, Emer (2005). Comparative Children's Literature. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 0415305519.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Carpenter 1981, p. 159

- ^ Zipes, Jack (2000). The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. p. 525. ISBN 0198601158.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b St.clair, Gloriana. "Tolkien's Cauldron: Northern Literature and The Lord of the Rings". Carnagie Mellon. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^ Brush, Nigel (2005). The Limitations of Scientific Truth. Kregel Publications. p. 108. ISBN 0825422531.

- ^ a b c d Sullivan, C. W. (1996). "High Fantasy". In Hunt, Peter (ed.). International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature. Taylor & Francis. pp. 309–310. ISBN 0415088569.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Timmerman, John (1983). Other Worlds. Popular Press. p. 52. ISBN 087972241X.

- ^ Pienciak, Anne (1986). Book Notes: "The Hobbit". Barron's Educational Series. pp. 36–39. ISBN 0812035232.

- ^ Auden, W. H. (2004). "The Quest Hero". In Rose A. Zimbardo and Neil D. Isaaca, (ed.). Understanding the Lord of the Rings: The Best of Tolkien Criticism. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 31–51. ISBN ISBN 0-618-42251-x.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b Helms, Randel (1976). Myth, Magic and Meaning in Tolkien's World. Granada. pp. 45–55. ISBN 0415921503.

- ^ Amison, Anne (2006). "An unexpected Guest. influence of William Morris on J. R. R. Tolkien's works". Mythlore (98).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Tolkien's Middle-earth: Lesson Plans, Unit Two". Houghton Mifflin. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- ^ a b Shippey, Tom: Tolkien: Author of the Century, HarperCollins, 2000, p.41

- ^ Grenby, Matthew (2008). Children's Literature. Edinburgh University Press. p. 98. ISBN 061847885X.

- ^ Chance, Jane (2001). Tolkien's Art. Kentucky University Press. pp. 53–56. ISBN 061847885X.

- ^ Grenby, Matthew (2008). Children's Literature. Edinburgh University Press. p. 162. ISBN 0748622748.

- ^ "The Hobbit Book Notes Summary: Topic Tracking - Greed". BookRags. Retrieved 5 2 5 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dateformat=(help) - ^ Clark, George (2000). J. R. R. Tolkien and His Literary Resonances: Views of Middle-earth. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 85–86. ISBN 0313308454.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rateliff 2007, pp. 603–609

- ^ a b Curry, Patrick (2004). Defending Middle-earth: Tolkien: Myth and Modernity. Mariner Books. p. 98. ISBN 061847885X.

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey (1979). The Inklings: C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Williams and Their Friends. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 43. ISBN 0-395-27628-4.

- ^ a b Carpenter 1981, p. 31

- ^ a b Hall, Mark F. (2006). "Dreaming of dragons: Tolkien's impact on Heaney's Beowulf". Mythlore.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Faraci, Mary (2002). "Chapter 5: "I wish to speak" (Tolkien's voice in his Beowulf essay)". In Chance, Jane (ed.). Tolkien the medievalist. Routledge. pp. 58–59. ISBN 0415289443.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Purtill, Richard L. (2006). Lord of the Elves and Eldils. Ignatius Press. pp. 53–55. ISBN 1586170848.

- ^ McDonald, R. Andrew (2006). ""In the hilt is fame": resonances of medieval swords and sword-lore in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings". Mythlore (96).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lobdell, Jared (1975). A Tolkien Compass. Open Court Publishing. p. 106. ISBN 0875483038.

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey (23). "Review: Cover book: Tolkien and the Great War by John Garth". The Times Online. Retrieved 05 2 5 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=,|date=, and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dateformat=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Croft, Janet Brennan (2003). ""The young perish and the old linger, withering": J. R. R. Tolkien on World War II". Mythlore (89).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Croft, Janet Brennan (2002). "The Great War and Tolkien's Memory, an examination of World War I themes in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings". Mythlore (84).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Zipes, Jack David (1999). When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 0415921503.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Anderson 2003, p. 18

- ^ Auden, W. H. (31/10/54). "The Hero is a Hobbit". New York Times. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "FAQ: Did Tolkien win any awards for his books?". Tolkien Society. 2002. Retrieved 28 June 2008.

- ^ Kocher, Paul (1974). "Master of Middle-earth, the Achievement of J. R. R. Tolkien". Penguin. pp. 22–23.

- ^ Rateliff 2007, p. xi

- ^ a b Kocher, Paul (1974). "Master of Middle-earth, the Achievement of J. R. R. Tolkien". Penguin. pp. 31–32.

- ^ Tolkien, Christopher (1983). The History of Middle-earth: Vol 1 "The Book of Lost Tales 1". George Allen & Unwin. p. 7. ISBN 0048232386.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Jones, Nicolette (30 April 2004). "What exactly is a children's book?". Times Online. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ "The Hobbit". Boys into Books (11-14). Schools Library Association. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ Carpenter 1981, p. 131

- ^ Elizabeth T. Lawrence (1987). "Glory Road: Epic Romance As An Allegory of 20th Century History; The World Through The Eyes Of J. R. R. Tolkien". Epic, Romance and the American Dream 1987 Volume II. Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ Zipes, Jack David (1979). Breaking the Magic Spell: Radical Theories of Folk and Fairy Tales. University Press of Kentucky. p. 173. ISBN 0813190304.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Millard, Elaine (1997). Differently Literate: boys, Girls and the Schooling of Literacy. Routledge. p. 164. ISBN 0750706619.

- ^ Lindrea, Victoria (29 July 2004). "How Tolkien triumphed over the critics". BBC. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Harlow, John (28 May 2008). "Hobbit movies meet dire foe in son of Tolkien". The Times Online. The Times. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Cieply, Michael (16 February 2008). "'The Rings' Prompts a Long Legal Mire". New York Times. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Andrews, Amanda (13 February 2008). "Tolkien's family threatens to block new Hobbit film". Times Online. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Tolkien Trust v. New Line Cinema Corp". FindLaw.com. 11 February 2008.

- ^ Bramlett, Perry C. (2003). I Am in Fact a Hobbit: An Introduction to the Life and Works of J. R. R. Tolkien. Mercer University Press. p. 239. ISBN 0865548943.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^

Kask, T. J. (1977). "NBC's The Hobbit". Dragon. III (6/7): 23.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Coyle, Jake (18 December 2007). "Peter Jackson to produce The Hobbit". USA Today. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

- ^ "Home of Middle Earth Strategic Gaming". ME Games Ltd. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^ Moore, Phil (1986). Using Computers in English: A Practical Guide. Routledge. p. 44. ISBN 0416361803.

- ^ Aarseth, Espen (2004). "Quest Games as Post-Narrative Discourse" in "Narrative Across Media: The Languages of Storytelling". University of Nebraska Press. p. 366. ISBN 0803239440.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Uffindell, Matthew (1984). "Playing The Game" (jpg). Crash. 1 (4): 43. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Campbell, Stuart (1991). "Top 100 Speccy Games". Your Sinclair. 1 (72): 22. Retrieved 6 July 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Tolkien's Hobbit fetches £60,000". bbc.co.uk. 18 March 2008. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ^ Jenny Holden (31 July 2008). "Books you Must Stock". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 5 July 2009.

- ^ "Hobbit fetches £6,000 at auction". BBC News. 26 November 2004. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- ^ Toby Walne (21 November 2007). "How to make a killing from first editions". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

References

- Anderson, Douglas A. (2003). The Annotated Hobbit. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-713726-3.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - Hammond, Wayne (1993). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Descriptive Bibliography. New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press. ISBN 0-938768-42-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Carpenter, Humphrey (1977). Tolkien: A Biography. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-04-928037-6.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-31555-7.

- Rateliff, John D. (2007). The History of the Hobbit. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-723555-1.

External links

- The official Tolkien website

- Collection of edition covers, 1937–2007

- The Hobbit covers around the globe – gallery

- Every UK edition of The Hobbit

- Guide to U.S. editions of Tolkien books including The Hobbit

- Literapedia notes for The Hobbit

- Complete Book Summary of The Hobbit.

- The Hobbit at the Internet Book List