Gross domestic product

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the market value[2] of all the final goods and services produced and rendered in a specific time period by a country[3] or countries.[4][5][6] GDP is often used to measure the economic health of a country or region.[3] Several national and international economic organizations maintain definitions of GDP, such as the OECD and the International Monetary Fund.[7][8]

The ratio of GDP to the total population of the region is the GDP per capita and can approximate a concept of a standard of living. Nominal GDP does not reflect differences in the cost of living and the inflation rates of the countries; therefore, using a basis of GDP per capita at purchasing power parity (PPP) may be more useful when comparing living standards between nations, while nominal GDP is more useful comparing national economies on the international market.[9] Total GDP can also be broken down into the contribution of each industry or sector of the economy.[10]

GDP is often used as a metric for international comparisons as well as a broad measure of economic progress. It is often considered to be the world's most powerful statistical indicator of national development and progress. However, critics of the growth imperative often argue that GDP measures were never intended to measure progress, and leave out key other externalities, such as resource extraction, environmental impact and unpaid domestic work.[11] Alternative economic indicators such as doughnut economics use other measures, such as the Human Development Index or Better Life Index, as better approaches to measuring the effect of the economy on human development and well being.

History

[edit]

William Petty came up with a concept of GDP, to calculate the tax burden, and argue landlords were unfairly taxed during warfare between the Dutch and the English between 1652 and 1674.[12] Charles Davenant developed the method further in 1695.[13]

The modern concept of GDP was first developed by Simon Kuznets for a 1934 U.S. Congress report, where he warned against its use as a measure of welfare (see below under limitations and criticisms).[14] After the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, GDP became the main tool for measuring a country's economy.[15] At that time gross national product (GNP) was the preferred estimate, which differed from GDP in that it measured production by a country's citizens at home and abroad rather than its "resident institutional units" (see OECD definition above). The switch from GNP to GDP in the United States occurred in 1991. The role that measurements of GDP played in World War II was crucial to the subsequent political acceptance of GDP values as indicators of national development and progress.[16] A crucial role was played here by the U.S. Department of Commerce under Milton Gilbert where ideas from Kuznets were embedded into institutions.

The history of the concept of GDP should be distinguished from the history of changes in many ways of estimating it. The value added by firms is relatively easy to calculate from their accounts, but the value added by the public sector, by financial industries, and by intangible asset creation is more complex. These activities are increasingly important in developed economies, and the international conventions governing their estimation and their inclusion or exclusion in GDP regularly change in an attempt to keep up with industrial advances. In the words of one academic economist, "The actual number for GDP is, therefore, the product of a vast patchwork of statistics and a complicated set of processes carried out on the raw data to fit them to the conceptual framework."[17]

China officially adopted GDP in 1993 as its indicator of economic performance. Previously, China had relied on a Marxist-inspired national accounting system.[18]

Determining gross domestic product (GDP)

[edit]

GDP can be determined in three ways, all of which should, theoretically, give the same result. They are the production (or output or value added) approach, the income approach, and the speculated expenditure approach. It is representative of the total output and income within an economy.

The most direct of the three is the production approach, which sums up the outputs of every class of enterprise to arrive at the total. The expenditure approach works on the principle that all of the products must be bought by somebody, therefore the value of the total product must be equal to people's total expenditures in buying things. The income approach works on the principle that the incomes of the productive factors ("producers", colloquially) must be equal to the value of their product, and determines GDP by finding the sum of all producers' incomes.[19]

Production approach

[edit]Also known as the Value Added Approach, it calculates how much value is contributed at each stage of production.

This approach mirrors the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) definition given above.

- Estimate the gross value of domestic output out of the many various economic activities;

- Determine the intermediate consumption, i.e., the cost of material, supplies and services used to produce final goods or services.

- Deduct intermediate consumption from gross value to obtain the gross value added.

Gross value added = gross value of output – value of intermediate consumption.

Value of output = value of the total sales of goods and services plus the value of changes in the inventory.

The sum of the gross value added in the various economic activities is known as "GDP at factor cost".

GDP at factor cost plus indirect taxes less subsidies on products = "GDP at producer price".

For measuring the output of domestic product, economic activities (i.e. industries) are classified into various sectors. After classifying economic activities, the output of each sector is calculated by any of the following two methods:

- By multiplying the output of each sector by their respective market price and adding them together

- By collecting data on gross sales and inventories from the records of companies and adding them together

The value of output of all sectors is then added to get the gross value of output at factor cost. Subtracting each sector's intermediate consumption from gross output value gives the GVA (=GDP) at factor cost. Adding indirect tax minus subsidies to GVA (GDP) at factor cost gives the "GVA (GDP) at producer prices".

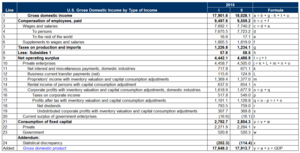

Income approach

[edit]The second way of estimating GDP is to use "the sum of primary incomes distributed by resident producer units".[7]

If GDP is calculated this way it is sometimes called gross domestic income (GDI), or GDP (I). GDI should provide the same amount as the expenditure method described later. By definition, GDI is equal to GDP. In practice, however, measurement errors will make the two figures slightly off when reported by national statistical agencies.

This method measures GDP by adding incomes that firms pay households for factors of production they hire – wages for labour, interest for capital, rent for land and profits for entrepreneurship.

The US "National Income and Product Accounts" divide incomes into five categories:

- Wages, salaries, and supplementary labor income

- Corporate profits

- Interest and miscellaneous investment income

- Income earned by sole proprietors and from the Housing subsector (net of expenses)

- Net income from transfer payments from businesses

These five income components sum to net domestic income at factor cost.

Two adjustments must be made to get GDP:

- Taxes on production and imports minus subsidies are added to get from factor cost to market prices.

- Depreciation (or capital consumption allowance) is added to get from net domestic product to gross domestic product.

Total income can be subdivided according to various schemes, leading to various formulae for GDP measured by the income approach. A common one is:[citation needed]

- GDP = + + +

- Compensation of employees (COE) measures the total remuneration to employees for work done. It includes wages and salaries, as well as employer contributions to social security and other such programs.

- Gross operating surplus (GOS) is the surplus due to owners of incorporated businesses. Often called profits, although only a subset of total costs are subtracted from gross output to calculate GOS.

- Gross mixed income (GMI) is the same measure as GOS, but for unincorporated businesses. This often includes most small businesses.

The sum of COE, GOS and GMI is called total factor income; it is the income of all of the factors of production in society. It measures the value of GDP at factor (basic) prices. The difference between basic prices and final prices (those used in the expenditure calculation) is the total taxes and subsidies that the government has levied or paid on that production. So adding taxes less subsidies on production and imports converts GDP(I) at factor cost to GDP(I) at final prices.

Total factor income is also sometimes expressed as:

- Total factor income = employee compensation + corporate profits + proprietor's income + rental income + net interest[20]

Expenditure approach

[edit]The third way to estimate GDP is to calculate the sum of the final uses of goods and services (all uses except intermediate consumption) measured in purchasers' prices.[7]

Market goods that are produced are purchased by someone. In the case where a good is produced and unsold, the standard accounting convention is that the producer has bought the good from themselves. Therefore, measuring the total expenditure used to buy things is a way of measuring production. This is known as the expenditure method of calculating GDP.

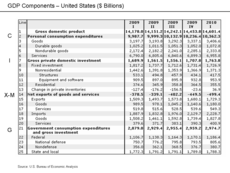

Components of GDP by expenditure

[edit]

GDP (Y) is the sum of consumption (C), investment (I), government expenditures (G) and net exports (X − M).

- Y = C + I + G + (X − M)

Here is a description of each GDP component:

- C (consumption) is normally the largest GDP component in the economy, consisting of private expenditures in the economy (household final consumption expenditure). These personal expenditures fall under one of the following categories: durable goods, nondurable goods, and services. Examples include food, rent, jewelry, gasoline, and medical expenses, but not the purchase of new housing.

- I (investment) includes, for instance, business investment in equipment, but does not include exchanges of existing assets. Examples include the construction of a new mine, the purchase of software, or the purchase of machinery and equipment for a factory. Spending by households (not the government) on new houses is also included in investment. In contrast to its colloquial meaning, "investment" in GDP does not mean purchases related to financial investments. Buying financial products is classed as 'saving', as opposed to investment. This avoids double-counting: if one buys shares in a company, and the company uses the money received to buy plant, equipment, etc., the amount will be counted toward GDP when the company spends the money on those things; to also count it when one gives it to the company would be to count two times an amount that only corresponds to one group of products. Buying bonds or companies' equity shares is a swapping of deeds, a transfer of claims on future production, not directly an expenditure on products; buying an existing building will involve a positive investment by the buyer and a negative investment by the seller, netting to zero overall investment.

- G (government spending) is the sum of government expenditures on final goods and services. It includes salaries of public servants, purchases of weapons for the military and any investment expenditure by a government. It does not include any transfer payments, such as social security or unemployment benefits. Analyses outside the US will often treat government investment as part of investment rather than government spending.

- X (exports) represents gross exports. GDP captures the amount a country produces, including goods and services produced for other nations' consumption, therefore exports are added.

- M (imports) represents gross imports. Imports are subtracted since imported goods will be included in the terms G, I, or C, and must be deducted to avoid counting foreign supply as domestic.

C, I, and G are expenditures on final goods and services; expenditures on intermediate goods and services do not count. (Intermediate goods and services are those used by businesses to produce other goods and services within the accounting year.[21]) So for example if a car manufacturer buys auto parts, assembles the car and sells it, only the final car sold is counted towards the GDP. Meanwhile, if a person buys replacement auto parts to install them on their car, those are counted towards the GDP.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, which is responsible for calculating the national accounts in the United States, "In general, the source data for the expenditures components are considered more reliable than those for the income components [see income method, above]."[22]

Encyclopedia Britannica records an alternate way of measuring exports minus imports: notating it as the single variable NX.[2][23]

GDP and GNI

[edit]GDP can be contrasted with gross national product (GNP) or, as it is now known, gross national income (GNI). The difference is that GDP defines its scope according to location, while GNI defines its scope according to ownership. In a global context, world GDP and world GNI are, therefore, equivalent terms.

GDP is a product produced within a country's borders; GNI is product produced by enterprises owned by a country's citizens. The two would be the same if all of the productive enterprises in a country were owned by its own citizens and those citizens did not own productive enterprises in any other countries. In practice, however, foreign ownership makes GDP and GNI non-identical. Production within a country's borders, but by an enterprise owned by somebody outside the country, counts as part of its GDP but not its GNI; on the other hand, production by an enterprise located outside the country, but owned by one of its citizens, counts as part of its GNI but not its GDP.

For example, the GNI of the US is the value of output produced by American-owned firms, regardless of where the firms are located. Similarly, if a country becomes increasingly in debt, and spends large amounts of income servicing this debt this will be reflected in a decreased GNI but not a decreased GDP. Similarly, if a country sells off its resources to entities outside their country this will also be reflected over time in decreased GNI, but not decreased GDP. This would make the use of GDP more attractive for politicians in countries with increasing national debt and decreasing assets.

Gross national income (GNI) equals GDP plus income receipts from the rest of the world minus income payments to the rest of the world.[24]

In 1991, the United States switched from using GNP to using GDP as its primary measure of production.[25] The relationship between United States GDP and GNP is shown in table 1.7.5 of the National Income and Product Accounts.[26]

Another example that amplifies the difference between GDP and GNI is the comparison of developed and developing country indicators. The GDP of Japan for 2020 is US$5,040,107.75 (in a million).[27] Predictably, as a developed country, Japan has a higher GNI (by 182,779.46, in millions of USD), which is indicative that the production level in the country is higher than that of national production.[28] On the other hand, the case with Armenia is the opposite, with GDP being lower than GNI by US$196.12 (in million). This demonstrates that countries receive investments and foreign aid from abroad.[29][30] The Total income divided by the population is the Per capita income.

International standards

[edit]The international standard for measuring GDP is contained in the book System of National Accounts (2008), which was prepared by representatives of the International Monetary Fund, European Union, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, United Nations and World Bank. The publication is normally referred to as SNA2008 to distinguish it from the previous edition published in 1993 (SNA93) or 1968 (called SNA68) [31]

SNA2008 provides a set of rules and procedures for the measurement of national accounts. The standards are designed to be flexible, to allow for differences in local statistical needs and conditions.

National measurement

[edit]

Within each country GDP is normally measured by a national government statistical agency, as private sector organizations normally do not have access to the information required (especially information on expenditure and production by governments).

Nominal GDP and adjustments to GDP

[edit]The raw GDP figure as given by the equations above is called the nominal, historical, or current GDP. When one compares GDP figures from one year to another, it is desirable to compensate for changes in the value of money—for the effects of inflation or deflation. To make it more meaningful for year-to-year comparisons, it may be multiplied by the ratio between the value of money in the year the GDP was measured and the value of money in a base year.

For example, suppose a country's GDP in 1990 was $100 million and its GDP in 2000 was $300 million. Suppose also that inflation had halved the value of its currency over that period. To meaningfully compare its GDP in 2000 to its GDP in 1990, we could multiply the GDP in 2000 by one-half, to make it relative to 1990 as a base year. The result would be that the GDP in 2000 equals $300 million × 1⁄2 = $150 million, in 1990 monetary terms. We would see that the country's GDP had realistically increased 50 percent over that period, not 200 percent, as it might appear from the raw GDP data. The GDP adjusted for changes in money value in this way is called the real GDP.

The factor used to convert GDP from current to constant values in this way is called the GDP deflator. Unlike consumer price index, which measures inflation or deflation in the price of household consumer goods, the GDP deflator measures changes in the prices of all domestically produced goods and services in an economy including investment goods and government services, as well as household consumption goods.[32]

GDP growth

[edit]

Real GDP can be used to calculate the GDP growth rate, which indicates how much a country's production has increased (or decreased, if the growth rate is negative) compared to the previous year, typically expressed as percentage change. The economic growth can be expressed as real GDP growth rate or real GDP per capita growth rate.

GDP per capita

[edit]

| > $60,000 $50,000–$60,000 $40,000–$50,000 $30,000–$40,000 | $20,000–$30,000 $10,000–$20,000 $5,000–$10,000 $2,500–$5,000 | $1,000–$2,500 < $1,000 No data |

| > $60,000 $50,000–$60,000 $40,000–$50,000 $30,000–$40,000 | $20,000–$30,000 $10,000–$20,000 $5,000–$10,000 $2,500–$5,000 | $1,000–$2,500 $500–$1,000 < $500 No data |

GDP can be adjusted for population growth, also called Per-capita GDP or GDP per person. This measures the average production of a person in the country.

Lists of GDP per capita

[edit]Standard of living: income distribution

[edit]

GDP per capita is often used as an indicator of living standards.[33]

The major advantage of GDP per capita as an indicator of the standard of living is that it is measured frequently, widely, and consistently. It is measured frequently in that most countries provide information on GDP every quarter, allowing trends to be seen quickly. It is measured widely in that some measure of GDP is available for almost every country in the world, allowing inter-country comparisons. It is measured consistently in that the technical definition of GDP is relatively consistent among countries.

GDP does not include several factors that influence the standard of living. In particular, it fails to account for:

- Externalities – Economic growth may entail an increase in negative externalities that are not directly measured in GDP.[34][35] Increased industrial output might grow GDP, but any pollution is not counted.[36]

- Non-market transactions – GDP excludes activities that are not provided through the market, such as household production, bartering of goods and services, and volunteer or unpaid services.

- Non-monetary economy – GDP omits economies where no money comes into play at all, resulting in inaccurate or abnormally low GDP figures. For example, in countries with major business transactions occurring informally, portions of local economy are not easily registered. Bartering may be more prominent than the use of money, even extending to services.[35]

- Quality improvements and inclusion of new products – by not fully adjusting for quality improvements and new products, GDP understates true economic growth. For instance, although computers today are less expensive and more powerful than computers from the past, GDP treats them as the same products by only accounting for their monetary value. The introduction of new products is also difficult to measure accurately and is not reflected in GDP although it may increase the standard of living. For example, even the richest person in 1900 could not purchase standard products, such as antibiotics and cell phones, that an average consumer can buy today, since such modern conveniences did not exist then.

- Sustainability of growth – GDP is a measurement of economic historic activity and is not necessarily a projection.

- Income distribution – GDP does not account for variances in incomes of various demographic groups. See income inequality metrics for discussion of a variety of inequality-based economic measures.[35]

It can be argued that GDP per capita as an indicator of standard of living is correlated with these factors, capturing them indirectly.[33][37] As a result, GDP per capita as a standard of living is a continued usage because most people have a fairly accurate idea of what it is and know it is tough to come up with quantitative measures for such constructs as happiness, quality of life, and well-being.[33] From the perspective of environmental, social and governance (ESG) measures, GDP per capita trends can be influenced by factors such as gender parity and elements of regulatory quality. In an example of a developing country with a mixed economy from 2008 to 2021, elements such as the per capita gross domestic product and the unemployment rate have a significant effect on the number of MSMEs in the Philippines.[38]

Limitations and criticisms

[edit]Limitations at introduction

[edit]Simon Kuznets, the economist who developed the first comprehensive set of measures of national income, stated in his second report to the U.S. Congress in 1937, in a section titled "Uses and Abuses of National Income Measurements":[14]

The valuable capacity of the human mind to simplify a complex situation in a compact characterization becomes dangerous when not controlled in terms of definitely stated criteria. With quantitative measurements especially, the definiteness of the result suggests, often misleadingly, a precision and simplicity in the outlines of the object measured. Measurements of national income are subject to this type of illusion and resulting abuse, especially since they deal with matters that are the center of conflict of opposing social groups where the effectiveness of an argument is often contingent upon oversimplification. [...] All these qualifications upon estimates of national income as an index of productivity are just as important when income measurements are interpreted from the point of view of economic welfare. But in the latter case additional difficulties will be suggested to anyone who wants to penetrate below the surface of total figures and market values. Economic welfare cannot be adequately measured unless the personal distribution of income is known. And no income measurement undertakes to estimate the reverse side of income, that is, the intensity and unpleasantness of effort going into the earning of income. The welfare of a nation can, therefore, scarcely be inferred from a measurement of national income as defined above.

In 1962, Kuznets stated:[39]

Distinctions must be kept in mind between quantity and quality of growth, between costs and returns, and between the short and long run. Goals for more growth should specify more growth of what and for what.

GDP as initially defined includes spending on goods and services that would shrink if underlying problems were solved or reduced - for example, medical care, crime-fighting, and the military. During World War II, Kuznets came to argue that military spending should be excluded during peacetime. This idea did not become popular; these activities are tracked because they fit into macroeconomic models (e.g. military spending uses up capital and labor).[40]

Further criticisms

[edit]Ever since the development of GDP, multiple observers have pointed out limitations of using GDP as the overarching measure of economic and social progress. For example, many environmentalists argue that GDP is a poor measure of social progress because it does not take into account harm to the environment.[41][42] Furthermore, the GDP does not consider human health nor the educational aspect of a population.[43]

American politician Robert F. Kennedy famously[44] criticized GDP (or GNP), listing many examples of bad things it does count and good things it does not count:

Gross National Product counts air pollution and cigarette advertising, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage. It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for the people who break them. It counts the destruction of the redwood and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl. It counts napalm and counts nuclear warheads and armored cars for the police to fight the riots in our cities. It counts Whitman's rifle and Speck's knife, and the television programs which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children. Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country, it measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile. And it can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.[45]

Although a high or rising level of GDP is often associated with increased economic and social progress, the opposite sometimes occurs. For example, Jean Drèze and Amartya Sen have pointed out that an increase in GDP or in GDP growth does not necessarily lead to a higher standard of living, particularly in areas such as healthcare and education.[46] Another important area that does not necessarily improve along with GDP is political liberty, which is most notable in China, where GDP growth is strong yet political liberties are heavily restricted.[47] GDP does not account for the distribution of income among the residents of a country, because GDP is merely an aggregate measure. An economy may be highly developed or growing rapidly, but also contain a wide gap between the rich and the poor in a society. These inequalities often occur on the lines of race, ethnicity, gender, religion, or other minority status within countries.[48] This can lead to misleading characterizations of economic well-being if the income distribution is heavily skewed toward the high end, as the poorer residents will not directly benefit from the overall level of wealth and income generated in their country (their purchasing power can decline, even as the mean GDP per capita rises). GDP per capita measures (like aggregate GDP measures) do not account for income distribution (and tend to overstate the average income per capita). For example, South Africa during apartheid ranked high in terms of GDP per capita, but the benefits of this immense wealth and income were not shared equally among its citizens.[49] The United Nations has aimed in its Sustainable Development Goals, amongst other global initiatives, to address wealth inequality.[50]

GDP excludes the value of household and other unpaid work. Some, including Martha Nussbaum, argue that this value should be included in measuring GDP, as household labor is largely a substitute for goods and services that would otherwise be purchased with money.[51] Even under conservative estimates, the value of unpaid labor in Australia has been calculated to be over 50% of the country's GDP.[52] A later study analyzed this value in other countries, with results ranging from a low of about 15% in Canada (using conservative estimates) to high of nearly 70% in the United Kingdom (using more liberal estimates). For the United States, the value was estimated to be between about 20% on the low end to nearly 50% on the high end, depending on the methodology being used.[53] Because many public policies are shaped by GDP calculations and by the related field of national accounts,[54] public policy might differ if unpaid work were included in total GDP. Some economists have advocated for changes in the way public policies are formed and implemented.[55]

The UK's Natural Capital Committee highlighted the shortcomings of GDP in its advice to the UK Government in 2013, pointing out that GDP "focuses on flows, not stocks. As a result, an economy can run down its assets yet, at the same time, record high levels of GDP growth, until a point is reached where the depleted assets act as a check on future growth". They then went on to say that "it is apparent that the recorded GDP growth rate overstates the sustainable growth rate. Broader measures of wellbeing and wealth are needed for this and there is a danger that short-term decisions based solely on what is currently measured by national accounts may prove to be costly in the long-term".

It has been suggested that countries that have authoritarian governments, such as the People's Republic of China, and Russia, inflate their GDP figures.[56]

Research and development about the relation between GDP and use of GDP and reality

[edit]

Instances of GDP measures have been considered numbers that are artificial constructs.[57] In 2020 scientists, as part of a World Scientists' Warning to Humanity-associated series, warned that worldwide growth in affluence in terms of GDP-metrics has increased resource use and pollutant emissions with affluent citizens of the world – in terms of e.g. resource-intensive consumption – being responsible for most negative environmental impacts and central to a transition to safer, sustainable conditions. They summarised evidence, presented solution approaches and stated that far-reaching lifestyle changes need to complement technological advancements and that existing societies, economies and cultures incite consumption expansion and that the structural imperative for growth in competitive market economies inhibits societal change.[58][59][60] Sarah Arnold, Senior Economist at the New Economics Foundation (NEF) stated that "GDP includes activities that are detrimental to our economy and society in the long term, such as deforestation, strip mining, overfishing and so on".[61] The number of trees that are net lost annually is estimated to be approximately 10 billion.[62][63] The global average annual deforested land in the 2015–2020 demi-decade was 10 million hectares and the average annual net forest area loss in the 2000–2010 decade 4.7 million hectares, according to the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020.[64] According to one study, depending on the level of wealth inequality, higher GDP-growth can be associated with more deforestation.[65] In 2019 "agriculture and agribusiness" accounted for 24% of the GDP of Brazil, where a large share of annual net tropical forest loss occurred and is associated with sizable portions of this economic activity domain.[66] The number of obese adults was approximately 600 million (12%) in 2015.[67] In 2013 scientists reported that large improvements in health only lead to modest long-term increases in GDP per capita.[68] After developing an abstract metric similar to GDP, the Center for Partnership Studies highlighted that GDP "and other metrics that reflect and perpetuate them" may not be useful for facilitating the production of products and provision of services that are useful – or comparatively more useful – to society, and instead may "actually encourage, rather than discourage, destructive activities".[69][70] Steve Cohen of the Earth Institute elucidated that while GDP does not distinguish between different activities (or lifestyles), "all consumption behaviors are not created equal and do not have the same impact on environmental sustainability".[71] Johan Rockström, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, noted that "it's difficult to see if the current G.D.P.-based model of economic growth can go hand-in-hand with rapid cutting of emissions", which nations have agreed to attempt under the Paris Agreement in order to mitigate real-world impacts of climate change.[72] Some have pointed out that GDP did not adapt to sociotechnical changes to give a more accurate picture of the modern economy and does not encapsulate the value of new activities such as delivering price-free information and entertainment on social media.[73] In 2017 Diane Coyle explained that GDP excludes much unpaid work, writing that "many people contribute free digital work such as writing open-source software that can substitute for marketed equivalents, and it clearly has great economic value despite a price of zero", which constitutes a common criticism "of the reliance on GDP as the measure of economic success" especially after the emergence of the digital economy.[74] Similarly GDP does not value or distinguish for environmental protection. A 2020 study found that "poor regions' GDP grows faster by attracting more polluting production after connection to China's expressway system.[75] GDP may not be a tool capable of recognizing how much natural capital agents of the economy are building or protecting.[76]

Proposals to overcome GDP limitations

[edit]In response to these and other limitations of using GDP, alternative approaches have emerged.

- In the 1980s, Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum developed the capability approach, which focuses on the functional capabilities enjoyed by people within a country, rather than the aggregate wealth held within a country. These capabilities consist of the functions that a person is able to achieve.[77]

- In 1990, Mahbub ul Haq, a Pakistani economist at the United Nations, introduced the Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI is a composite index of life expectancy at birth, adult literacy rate and standard of living measured as a logarithmic function of GDP, adjusted to purchasing power parity.

- In 1989, John B. Cobb and Herman Daly introduced Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare (ISEW) by taking into account other factors such as consumption of nonrenewable resources and degradation of the environment. ISEW is roughly defined as: personal consumption + public non-defensive expenditures − private defensive expenditures + capital formation + services from domestic labour − costs of environmental degradation − depreciation of natural capital

- In 2005, Med Jones, an American Economist, at the International Institute of Management, introduced the first secular Gross National Happiness Index a.k.a. Gross National Well-being framework and Index to complement GDP economics with additional seven dimensions, including environment, education, and government, work, social and health (mental and physical) indicators. The proposal was inspired by the King of Bhutan's GNH philosophy.[78][79][80]

- In 2009 the European Union released a communication titled GDP and beyond: Measuring progress in a changing world[81] that identified five actions to improve indicators of progress in ways that make them more responsive to the concerns of its citizens.

- In 2009 Professors Joseph Stiglitz, Amartya Sen, and Jean-Paul Fitoussi at the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress (CMEPSP), formed by French President, Nicolas Sarkozy published a proposal to overcome the limitation of GDP economics to expand the focus to well-being economics with a well-being framework consisting of health, environment, work, physical safety, economic safety, and political freedom. This has been adopted in a number of countries as a wellbeing economy policy.

- In 2008, the Centre for Bhutan Studies began publishing the Bhutan Gross National Happiness (GNH) Index, whose contributors to happiness include physical, mental, and spiritual health; time balance; social and community vitality; cultural vitality; education; living standards; good governance; and ecological vitality.[82]

- In 2013, the OECD Better Life Index was published by the OECD. The dimensions of the index included health, economic, workplace, income, jobs, housing, civic engagement, and life satisfaction.

- Since 2012, John Helliwell, Richard Layard and Jeffrey Sachs have edited an annual World Happiness Report which reports a national measure of subjective well-being, derived from a single survey question on satisfaction with life. GDP explains some of the cross-national variation in life satisfaction, but more of it is explained by other, social variables (See 2013 World Happiness Report).

- In 2019, Serge Pierre Besanger published a "GDP 3.0" proposal which combines an expanded GNI formula which he calls GNIX, with a Palma ratio and a set of environmental metrics based on the Daly Rule.[83]

- In 2019, Erik Brynjolfsson and Avinash Collis argued that GDP does not reflect the growing value of many digital goods because they have zero price.[84] Along with several coauthors, they proposed an alternative approach, GDP-B, which is based on measuring the benefits of goods and services, rather than their price or cost.[85]

- At the beginning of the 21st century the World Economic Forum published a series of analyses and propositions to create economic measurement tools more effective than GDP.[86]

- China launched the Gross Ecosystem Product (GEP) in 2020. It measures the contribution of ecosystems to the economy, including by regulating climate. It spread widely across the country. The first province to issue local rules about GEP was Zhejiang , and a year later it has already decided the fate of a project in the Deqing region. For example, the GEP of Chengtian Radon Spring Nature Reserve has been calculated as US$43 million.[87]

Problems with GDP data

[edit]A peer-reviewed study published in the Journal of Political Economy in October 2022 found signs of manipulation of economic growth statistics in the majority of countries.[88] According to the study, this mainly applied to countries that were governed semi-authoritarian/authoritarian or did not have a functioning separation of powers. The study took the annual growth in the brightness of lights at night, as measured by satellites, and compared it to officially reported economic growth. Authoritarian states had consistently higher reported growth in GDP than their growth in night lights would suggest. An effect that also cannot be explained by different economic structures, sector composition or other factors. Incorrect growth statistics can also falsify indicators such as GDP or GDP per capita.[89]

Lists of countries by their GDP

[edit]- List of continents by GDP

- Lists of countries by GDP

- List of countries by GDP (nominal), (per capita)

- List of countries by GDP (PPP), (per capita)

- List of countries by GDP sector composition

- List of countries by past and projected GDP (PPP), (per capita), (nominal), (nominal per capita)

- List of countries by real GDP growth rate, (real GDP per capita growth)

See also

[edit]- Chained volume series

- Circular flow of income

- Composite Index of National Capability

- Cost-of-living crisis

- Disposable household and per capita income

- Economy monetization

- GDP density

- Gross regional domestic product

- Inventory investment

- List of countries by average wage

- List of countries by GNI per capita growth

- List of economic reports by U.S. government agencies

- Misery index (economics)

- Median income

- Modified gross national income

- National average salary

- Potential output

- Productivism

- Social Progress Index

References

[edit]- ^ "GDP (Official Exchange Rate)" (PDF). World Bank. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-12. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ a b Duigpan, Brian (2017-02-28). "gross domestic product". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2023-02-25. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ a b "gross domestic product (GDP) – Students". Britannica Kids. Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2023-02-23. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ Callen, Tim. "Gross Domestic Product: An Economy's All". Finance & Development | F&D. International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 30 October 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "Gross Domestic Product". Bureau of Economic Analysis. Archived from the original on 13 December 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ "Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Definition". Britannica Money. Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2023-02-23. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ a b c "OECD". Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ Callen, Tim. "Gross Domestic Product: An Economy's All". IMF. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ Hall, Mary. "What Is Purchasing Power Parity (PPP)?". Investopedia. Archived from the original on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- ^ Dawson, Graham (2006). Economics and Economic Change. FT / Prentice Hall. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-273-69351-2.

- ^ Raworth, Kate (2017). Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. ISBN 978-1-84794-138-1. OCLC 974194745. Archived from the original on 2021-04-29. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ "Petty impressive". The Economist. 21 December 2013. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ Coyle, Diane (6 April 2014). "Warfare and the Invention of GDP". The Globalist. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ a b Congress commissioned Kuznets to create a system that would measure the nation's productivity in order to better understand how to tackle the Great Depression.Simon Kuznets, 1934. "National Income, 1929–1932". 73rd U.S. Congress, 2d session, Senate document no. 124, page 5–7 Simon Kuznets, 1934. "National Income, 1929–1932". 73rd U.S. Congress, 2d session, Senate document no. 124, page 5–7 Simon Kuznets, 1934. "National Income, 1929–1932". 73rd U.S. Congress, 2d session, Senate document no. 124, page 5–7. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/971 Archived 2018-09-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dickinson, Elizabeth. "GDP: a brief history". Foreign Policy. ForeignPolicy.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2014. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Lepenies, Philipp (April 2016). The Power of a Single Number: A Political History of GDP. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54143-5. Archived from the original on 2017-10-20. Retrieved 2017-10-09.

- ^ Coyle, Diane (2014). GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History. Princeton University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-691-15679-8.

- ^ Heijster, Joan van; DeRock, Daniel (29 October 2020). "How GDP spread to China: the experimental diffusion of macroeconomic measurement". Review of International Political Economy. 29: 65–87. doi:10.1080/09692290.2020.1835690. ISSN 0969-2290.

- ^ "GDP – Final Output". Statistical Manual. World Bank. Archived from the original on 16 April 2010, retrieved October 2009.

"User's guide: Background information on GDP and GDP deflator". HM Treasury. Archived from the original on 2 March 2009.

"Measuring the Economy: A Primer on GDP and the National Income and Product Accounts" (PDF). Bureau of Economic Analysis. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-09-16. - ^ United States Bureau of Economic Analysis, "A guide to the National Income and Product Accounts of the United States" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-06-04., page 5; retrieved November 2009. Another term, "business current transfer payments", may be added. Also, the document indicates that the capital consumption adjustment (CCAdj) and the inventory valuation adjustment (IVA) are applied to the proprietor's income and corporate profits terms; and CCAdj is applied to rental income.

- ^ Thayer Watkins, San José State University Department of Economics, "Gross Domestic Product from the Transactions Table for an Economy" Archived 2012-08-25 at the Wayback Machine, commentary to the first table, " Transactions Table for an Economy". (Page retrieved November 2009.)

- ^ Concepts and Methods of the United States National Income and Product Accounts, chap. 2.

- ^ "gross domestic product – Scholars". Britannica Kids. Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2023-02-23. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ Lequiller, François; Derek Blades (2006). Understanding National Accounts. OECD. p. 18. ISBN 978-92-64-02566-0. Archived from the original on 2023-03-12. Retrieved 2021-02-15.

To convert GDP into GNI, it is necessary to add the income received by resident units from abroad and deduct the income created by production in the country but transferred to units residing abroad.

- ^ United States, Bureau of Economic Analysis, Glossary, "GDP" Archived 29 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved November 2009.

- ^ "U.S. Department of Commerce. Bureau of Economic Analysis". Bea.gov. 21 October 2009. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ [1] Archived 2022-12-07 at the Wayback Machine, GDP (current US$) – Japan

- ^ [2] Archived 2022-12-07 at the Wayback Machine, GNI (current US$) – Japan

- ^ [3] Archived 2022-12-07 at the Wayback Machine, GNI (current US$) – Armenia

- ^ [4] Archived 2022-12-07 at the Wayback Machine, GDP (current US$) – Armenia

- ^ "National Accounts". Central Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 16 April 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ^ HM Treasury, Background information on GDP and GDP deflator

Some of the complications involved in comparing national accounts from different years are explained in this World Bank document Archived 16 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine. - ^ a b c "How Do We Measure Standard of Living?" (PDF). The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-03-31.

- ^ Mankiw, N. G.; Taylor, M. P. (2011). Economics (2nd, revised ed.). Andover: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-84480-870-0.

- ^ a b c "Macroeconomics – GDP and Welfare". Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ Choi, Kwan. "Gross Domestic Product". Introduction to the World Economy. Archived from the original on 2020-09-24. Retrieved 2020-06-24.

- ^ "How Real GDP per Capita Affects the Standard of Living". Study.com. Archived from the original on 2015-05-20. Retrieved 2015-04-06.

- ^ Tan, Jackson; Arceo, Virginia (2024-08-24). "Women driving Philippine entrepreneurship: Social and governance issues as mediated by economic development". Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research. https://rdcu.be/dRUEh

- ^ Simon Kuznets. "How To Judge Quality". The New Republic, 20 October 1962

- ^ Timothy Taylor (February 5, 2019). "Why Did Simon Kuznets Want to Leave Military Spending out of GDP?". Conversable Economist.

- ^ van den Bergh, Jeroen (13 April 2010). "The Virtues of Ignoring GDP". The Broker. Archived from the original on 24 February 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ Gertner, Jon (13 May 2010). "The Rise and Fall of G.D.P.". New York Times Magazine. Archived from the original on 2022-01-02.

- ^ "What Are the Advantages & Disadvantages of the GDP in Macroeconomics?". Bizfluent. Archived from the original on 2021-05-07. Retrieved 2021-05-07.

- ^ Suzuki, Dabid (February 28, 2014). "How the GDP Measures Everything 'Except That Which Makes Life Worthwhile'". EcoWatch. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ Remarks at the University of Kansas, March 18, 1968

- ^ Drèze, Jean; Sen, Amartya (2013). An Uncertain Glory: India and its Contradictions. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4877-5.

- ^ "China Country Report Freedom in the World 2012". Freedom House. 19 March 2012. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ "Inequality hurts economic growth, finds OECD research". OECD. 2014. Archived from the original on 2022-04-19. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ^ "South Africa Economic Update" (PDF). World Bank. April 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-06-13.

- ^ "Goal 10 targets". UNDP. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ Nussbaum, Martha C. (2013). Creating capabilities : the human development approach. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-07235-0.

- ^ Blades, François; Lequiller, Derek (2006). Understanding national accounts (Reprint ed.). Paris: OECD. p. 112. ISBN 978-92-64-02566-0.

- ^ "Incorporating Estimates of Household Production of Non-Market Services into International Comparisons of Material Well-Being". Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Économiques. 14 Oct 2011. STD/DOC(2011)7. Archived from the original on 2017-10-20. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

- ^ Holcombe, Randall G. (2004). "National Income Accounting and Public Policy" (PDF). Review of Austrian Economics. 17 (4): 387–405. doi:10.1023/B:RAEC.0000044638.48465.df. S2CID 30021697. Archived (PDF) from the original on Oct 6, 2022 – via George Mason University.

- ^ "National Accounts: A Practical Introduction" (PDF). UNSD. 2003. ST/ESA/STAT/SER.F/85. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2005-12-27.

- ^ Ingraham, Christopher (15 May 2018). "Satellite data strongly suggests that China, Russia and other authoritarian countries are fudging their GDP reports". SFGate. San Francisco. Washington Post. Archived from the original on 15 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ Pilling, David (4 July 2014). "Has GDP outgrown its use?". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 8 September 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ Wiedmann, Thomas; Steinberger, Julia K.; Lenzen, Manfred (June 24, 2020). "Affluence is killing the planet, warn scientists". phys.org. The Conversation. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "Overconsumption and growth economy key drivers of environmental crises". phys.org. University of New South Wales. June 19, 2020. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ Thomas Wiedmann; Manfred Lenzen; Lorenz T. Keyßer; Julia Steinberger (19 June 2020). "Scientists' warning on affluence". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 3107. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.3107W. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16941-y. PMC 7305220. PMID 32561753.

Text and image were copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

Text and image were copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Goldsmith, Courtney. "Why GDP is no longer the most effective measure of economic success". World Finance. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ Dunham, Will (2 September 2015). "Earth has 3 trillion trees but they're falling at alarming rate". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (4 July 2019). "Tree planting 'has mind-blowing potential' to tackle climate crisis". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "Global Forest Resource Assessment 2020". Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ Koop, Gary; Tole, Lise (1 October 2001). "Deforestation, distribution and development". Global Environmental Change. 11 (3): 193–202. Bibcode:2001GEC....11..193K. doi:10.1016/S0959-3780(00)00057-1. ISSN 0959-3780. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ Arruda, Daniel; Candido, Hugo G.; Fonseca, Rúbia (27 September 2019). "Amazon fires threaten Brazil's agribusiness". Science. 365 (6460): 1387. Bibcode:2019Sci...365.1387A. doi:10.1126/science.aaz2198. PMID 31604261. S2CID 203566011. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, Lee A, Marczak L, Mokdad AH, Moradi-Lakeh M, Naghavi M, Salama JS, Vos T, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Ahmed MB, Al-Aly Z, Alkerwi A, Al-Raddadi R, Amare AT, Amberbir A, Amegah AK, Amini E, Amrock SM, Anjana RM, Ärnlöv J, Asayesh H, Banerjee A, Barac A, Baye E, Bennett DA, Beyene AS, Biadgilign S, Biryukov S, Bjertness E, Boneya DJ, Campos-Nonato I, Carrero JJ, Cecilio P, Cercy K, Ciobanu LG, Cornaby L, Damtew SA, Dandona L, Dandona R, Dharmaratne SD, Duncan BB, Eshrati B, Esteghamati A, Feigin VL, Fernandes JC, Fürst T, Gebrehiwot TT, Gold A, Gona PN, Goto A, Habtewold TD, Hadush KT, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hay SI, Horino M, Islami F, Kamal R, Kasaeian A, Katikireddi SV, Kengne AP, Kesavachandran CN, Khader YS, Khang YH, Khubchandani J, Kim D, Kim YJ, Kinfu Y, Kosen S, Ku T, Defo BK, Kumar GA, Larson HJ, Leinsalu M, Liang X, Lim SS, Liu P, Lopez AD, Lozano R, Majeed A, Malekzadeh R, Malta DC, Mazidi M, McAlinden C, McGarvey ST, Mengistu DT, Mensah GA, Mensink GB, Mezgebe HB, Mirrakhimov EM, Mueller UO, Noubiap JJ, Obermeyer CM, Ogbo FA, Owolabi MO, Patton GC, Pourmalek F, Qorbani M, Rafay A, Rai RK, Ranabhat CL, Reinig N, Safiri S, Salomon JA, Sanabria JR, Santos IS, Sartorius B, Sawhney M, Schmidhuber J, Schutte AE, Schmidt MI, Sepanlou SG, Shamsizadeh M, Sheikhbahaei S, Shin MJ, Shiri R, Shiue I, Roba HS, Silva DA, Silverberg JI, Singh JA, Stranges S, Swaminathan S, Tabarés-Seisdedos R, Tadese F, Tedla BA, Tegegne BS, Terkawi AS, Thakur JS, Tonelli M, Topor-Madry R, Tyrovolas S, Ukwaja KN, Uthman OA, Vaezghasemi M, Vasankari T, Vlassov VV, Vollset SE, Weiderpass E, Werdecker A, Wesana J, Westerman R, Yano Y, Yonemoto N, Yonga G, Zaidi Z, Zenebe ZM, Zipkin B, Murray CJ (July 2017). "Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years". The New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1614362. PMC 5477817. PMID 28604169.

- ^ Ashraf, Quamrul H.; Lester, Ashley; Weil, David N. (2009). "When Does Improving Health Raise GDP?". NBER Macroeconomics Annual. 23: 157–204. doi:10.1086/593084. ISSN 0889-3365. PMC 3860117. PMID 24347816.

- ^ "Social Wealth Index". The Center for Partnership Studies. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ Gansbeke, Frank Van. "Climate Change And Gross Domestic Product – Need For A Drastic Overhaul". Forbes. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- ^ "Economic growth and environmental sustainability". phys.org. Archived from the original on 3 November 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Landler, Mark; Sengupta, Somini (21 January 2020). "Trump and the Teenager: A Climate Showdown at Davos". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Kapoor, Amit; Debroy, Bibek (4 October 2019). "GDP Is Not a Measure of Human Well-Being". Harvard Business Review. Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Coyle, Diane (March 2017). "Rethinking GDP". Finance & Development. Vol. 54, no. 1. International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 2 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ He, Guojun; Xie, Yang; Zhang, Bing (1 June 2020). "Expressways, GDP, and the environment: The case of China". Journal of Development Economics. 145: 102485. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2020.102485. ISSN 0304-3878. S2CID 203596268. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Desai, Pooran (May 31, 2018). "GDP is destroying the planet. Here's an alternative". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Shahani, Lila; Deneulin, Severine (2009). An Introduction to the Human Development and Capability : Approach (1st ed.). London: Earthscan Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84407-806-6.

- ^ "Gross National Happiness (GNH) – A New Socioeconomic Development Policy Framework – A Policy White Paper – The American Pursuit of Unhappiness – Med Jones, IIM". Iim-edu.org. 10 January 2005. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ "Happiness Ministry in Dubai". 11 February 2016. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ "Harvard Kennedy School Report to U.S. Congressman 21st Century GDP: National Indicators for a New Era" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-01. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- ^ "GDP and beyond: Measuring progress in a changing world". European Union. 2009. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ^ ""Bhutan GNH Index"". Archived from the original on 2015-02-12. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- ^ "Death by GDP – how the climate crisis is driven by a growth yardstick". The Straits Times. 21 December 2019. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ^ Brynjolfsson, Erik; Collis, Avinash (2019-11-01). "How Should We Measure the Digital Economy?". Harvard Business Review. ISSN 0017-8012. Retrieved 2024-01-21.

- ^ Brynjolfsson, Erik; Collis, Avinash; Diewert, W. Erwin; Eggers, Felix; Fox, Kevin J. (March 2019), GDP-B: Accounting for the Value of New and Free Goods in the Digital Economy (Working Paper), Working Paper Series, doi:10.3386/w25695, hdl:1959.4/unsworks_59015, retrieved 2024-01-21

- ^ "Beyond GDP". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Mengnan, Jiang (4 April 2024). "Zhejiang counts 'gross ecosystem product' of nature reserve". China Dialogue. Retrieved 7 April 2024.

- ^ "A study of lights at night suggests dictators lie about economic growth". The Economist. Sep 29, 2022. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 2022-10-24. Retrieved 2022-10-25.

- ^ Martínez, Luis R. (2022-10-01). "How Much Should We Trust the Dictator's GDP Growth Estimates?". Journal of Political Economy. 130 (10): 2731–2769. doi:10.1086/720458. ISSN 0022-3808. S2CID 158256267. Archived from the original on 2022-12-06. Retrieved 2022-12-01.

Further reading

[edit]- Australian Bureau for Statistics, Australian National Accounts: Concepts, Sources and Methods (Archived 2008-08-17 at the Wayback Machine), 2000. Retrieved November 2009. In depth explanations of how GDP and other national account items are determined.

- Coyle, Diane (2014). GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15679-8.

- Jerven, Morten (2013). Poor Numbers: How We Are Misled by African Development Statistics and What to Do about It. Cornell University Press.

- Lepenies, Philipp. The Power of a Single Number: A Political History of GDP.

- Philipsen, Dirk. The Little Big Number: How GDP Came to Rule the World and What to Do About It.

- Joseph E. Stiglitz, "Measuring What Matters: Obsession with one financial figure, GDP, has worsened people's health, happiness and the environment, and economists want to replace it", Scientific American, vol. 323, no. 2 (August 2020), pp. 24–31.

- Susskind, Daniel (2024). Growth: A History and a Reckoning. Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674294493.

- Concepts and Methods of the United States National Income and Product Accounts (PDF). United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2018. In-depth explanations of how GDP and other national account items are determined.

External links

[edit]Global

- Gross domestic product at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Australian Bureau of Statistics Manual on GDP measurement

- OECD GDP chart

- UN Statistical Databases

- World Development Indicators (WDI) at World Bank

- World GDP Chart (since 1960)

Data

- Bureau of Economic Analysis: Official United States GDP data

- Historicalstatistics.org: Links to historical statistics on GDP for countries and regions, maintained by the Department of Economic History at Stockholm University

- Historical U.S. GDP (yearly data), 1790–present, maintained by Samuel H. Williamson and Lawrence H. Officer, both professors of economics at the University of Illinois at Chicago

- The Maddison Project of the Groningen Growth and Development Centre at the University of Groningen. This project extends the work of Angus Maddison in collating all the available, credible data estimating GDP for countries around the world. This includes data for some countries for over 2,000 years and for all countries since 1950.

Articles and books

- Callen, Tim. "Gross Domestic Product: An Economy's All". International Monetary Fund.

- Stiglitz, JE; Sen, A; Fitoussi, J-P (2010). "Mismeasuring our Lives: Why GDP Doesn't Add Up". New Press. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013.

- "What's wrong with the GDP?", The Genuine progress indicator: Summary of Data and Methodology, Redefining Progress C1995

- Whether output and CPI inflation are mismeasured, by Nouriel Roubini and David Backus, in Lectures in Macroeconomics

- Rodney Edvinsson, Edvinsson, Rodney (2005). "Growth, Accumulation, Crisis: With New Macroeconomic Data for Sweden 1800–2000". Diva.

- Clifford Cobb, Ted Halstead and Jonathan Rowe. "If the GDP is up, why is America down?" The Atlantic Monthly, vol. 276, no. 4, October 1995, pages 59–78

- Jerorn C.J.M. van den Bergh, "Abolishing GDP"

- GDP and GNI in OECD Observer No246-247, Dec 2004-Jan 2005