HMT Aragon

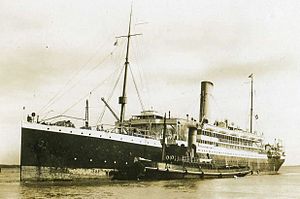

Aragon in 1908 as a civilian ocean liner

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Namesake | The Spanish Kingdom of Aragon |

| Owner | |

| Operator |

|

| Port of registry | Belfast |

| Route |

|

| Builder | Harland and Wolff, Belfast |

| Yard number | 367 |

| Launched | 23 February 1905[1] |

| Completed | 22 June 1905 |

| Maiden voyage | 14 July 1905 |

| Out of service | 30 December 1917 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Sunk by torpedo 30 December 1917 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | RMSP "A" series |

| Type | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage | |

| Length | 513.2 ft (156.4 m)[3] |

| Beam | 60.4 ft (18.4 m)[3] |

| Depth | 31.0 ft (9.4 m)[3] |

| Installed power | 762,[6] 827[3] or 875[1] NHP |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | |

| Boats & landing craft carried | 12 lifeboats, 1 dinghy, 1 gig |

| Capacity | |

| Crew | As troop ship: 200[3] |

| Armament | 2 × stern-mounted QF 4.7-inch (120 mm) guns (from 1913)[4] |

| Notes |

|

HMT Aragon, originally RMS Aragon, was a 9,588 GRT[3] transatlantic Royal Mail Ship that served as a troop ship in the First World War. She was built in Belfast, Ireland in 1905 and was the first of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company's fleet of "A-liners"[7] that worked regular routes between Southampton and South American ports including Buenos Aires.[2]

In 1913 Aragon became Britain's first defensively armed merchant ship ("DAMS") of modern times. In the First World War she served as a troop ship, taking part in the Gallipoli Campaign in 1915. In 1917, a German submarine sank her in the Mediterranean, killing 610 of the personnel aboard.

Building[edit]

Owen Philipps became chairman of RMSP in 1903 and quickly addressed the company's need for larger ships on its South America route. RMSP ordered Aragon from Harland and Wolff, who built her on slip number 7 of its South Yard in Belfast.[8] The Countess Fitzwilliam[5] launched her on 23 February 1905.[3] Harland and Wolff completed the ship on 22 June.[6]

Philipps had discussed with Charles Parsons the possibility of steam turbine propulsion, which had been demonstrated by the steam launch Turbinia in 1894. The first turbine-powered passenger ship, TS King Edward, had entered service on the Firth of Clyde in 1901 but Philipps decided that another year of evaluation was needed to establish if and how to apply the new form of steam power to commercial ships.[9]

Accordingly, Aragon was built with a pair of conventional quadruple-expansion steam engines.[3] Their combined power is variously quoted as 762,[6] 827[3] or 875[1] NHP. They drove twin screws[4] that gave her a speed of 15 knots (28 km/h).[3]

Aragon had a single large funnel amidships.[7] She had 12 lifeboats on her boat deck plus a dinghy and a gig aft.[10] Her first class dining saloon had a panelled ceiling inlaid with paintings of Christopher Columbus discovering the Americas.[11]

Aragon had five cargo holds, some of which were refrigerated to carry meat and fruit from South America. Number 5 hold and the lower levels of numbers 1 and 2 holds were for frozen cargos. The 'tween decks of numbers 1 and 2 holds and upper 'tween deck of number 5 hold were for chilled cargos. A steam-powered refrigerating plant used "carbonic anhydride" as the refrigerant, and the holds were insulated with "silicate cotton".[12] Her bunkers held 2,000 tons of coal[10] and she had water tanks with a capacity of about 2,000 tons.[12]

RMSP registered Aragon at Belfast. Her UK official number was 120707 and her code letters were HCST.[13]

A-series development[edit]

Aragon was followed by series of generally similar but progressively larger and heavier liners.[7] In 1906 Harland and Wolff built sister ships Amazon and Avon, while another Belfast shipyard, Workman, Clark and Company, built Araguaya. Harland and Wolff added a fifth sister ship, Asturias, in 1908. RMSP gave each of this series a name beginning with "A", with the result that colloquially they were dubbed the "A-series"[7] or "A-liners".

A few years later the final four A-series ships followed from Harland and Wolff: Arlanza in 1912, Andes and Alcantara in 1913 and Almanzora in 1915.[5] Apart from being larger again, they differed from Aragon and her first four sisters by having three screws instead of two, and by making limited use of the turbine propulsion that Phillips and Parsons had discussed a few years earlier. Their two outer screws were driven by conventional triple-expansion steam engines. A low-pressure steam turbine drove the middle screw via reduction gearing.[10]

Civilian service[edit]

From the 1850s RMSP passenger liners had served a regular route between Britain and the River Plate ports in South America. They sailed from Southampton in southern England, called at the islands of Madeira and Tenerife off the West African coast; at Pernambuco, Salvador de Bahia and Rio de Janeiro on the coast of Brazil; and then at Montevideo in Uruguay before completing their voyage at Buenos Aires in Argentina.[7] Aragon and her sisters modernised RMSP's Southampton – River Plate service,[2][4] replacing vessels such as RMS Atranto that had been in service from 1889 onwards.[7]

The A-series ships hugely increased the profitability of the route. In 1906 she made four voyages to and from South America and netted a total profit of £45,368.[14] In 1908 she ran aground off the Isle of Wight, but that aside her civilian service was generally uneventful.[15]

By 1913 Aragon was equipped for wireless telegraphy, operating on the 300 and 600 metre wavelengths. Her call sign was MBN.[16]

Defensively armed merchant ship[edit]

From the turn of the 20th century, growing tensions between Europe's Great Powers included an Anglo-German naval arms race that threatened the security of merchant shipping. From 1911 the British Intelligence became aware that the German Empire was secretly arming some of its passenger liners, and the UK Government and British Admiralty discussed how to respond.[17]

Towards the end of 1912 the Admiralty decided to match the German policy by arming some British passenger liners, starting with RMS Aragon.[18] She was due to carry naval guns from December 1912, but within the British Government and Admiralty there was uncertainty as to how foreign countries and ports would react.[19] In January 1913 Rear Admiral Henry Campbell recommended that the Admiralty should send a merchant ship to sea with naval guns, but without ammunition, to test foreign governments' reaction.[19] A meeting chaired by Sir Francis Hopwood, Civil Lord of the Admiralty agreed, and Sir Eyre Crowe recorded "If nothing happens, it may be possible and easy, after a time, to place ammunition on board."[19]

On 25 April 1913 Aragon left Southampton as Britain's first defensively armed merchant ship (DAMS), carrying two QF 4.7-inch (120 mm) naval guns on her stern.[4] Governments, newspapers and the public in South American countries that Aragon visited took little notice and expressed no concern.[2] There was criticism from some serving and retired naval figures in Britain[20] but the policy continued. Aragon's sister ship RMS Amazon was made the next DAMS, and in the following months further RMSP "A-liners" were armed.[4] They included the newly built Alcantara, which in the First World War served as an armed merchant cruiser.

Gallipoli[edit]

During the First World War the ship was requisitioned as a troop ship and became HMT Aragon. She took part in the Gallipoli Campaign, in which one source states that she began by taking the 5th Battalion, the Hampshire Regiment and Royal Army Medical Corps units to the campaign in March 1915.[21] As the landings were not until 25 April, this may refer to troops moving from the UK to the Eastern Mediterranean in preparation for the landings. Her duties included evacuating nearly 1,500 wounded personnel to Alexandria and Malta.[21]

On 8 April Aragon was in Alexandria where she embarked the 4th Battalion, the Worcestershire Regiment and the 2nd Battalion, the Hampshire Regiment.[22][23] Both battalions were units of the 88th Brigade, which as part of the 29th Division had been ordered to take part in the Gallipoli Landings.[23]

On 11 April she left Alexandria for the Aegean island of Lemnos, where French and British ships were assembling in the large natural harbour of Moudros in final preparation for the landings.[22][23] On 13 April 1915 Aragon's troops transferred to the cargo steamer SS River Clyde[5] in preparation for the landing at Cape Helles 10 days later.

Later in the Gallipoli Campaign a British Forces Post Office, Base Army Post Office Y, transferred from Arcadian, another troop ship, to Aragon.[24] BAPO Y later redeployed from Aragon to a land base at Moudros.[24]

The invasion was a costly failure and in January 1916 French and British forces withdrew from the Gallipoli peninsula. On 13 February Aragon left Moudros for Malta, taking troops on leave including four officers and 270 men of the 63rd (Royal Naval) Division (RND).[25]

On 14 May Aragon was again at Moudros to withdraw troops; this time including the 1st Battalion the Royal Marines[26] and elements of the 2nd (Royal Naval) Brigade.[25] She reached Marseille in southern France at 0630 hrs on 19 May.[26]

Later in 1916 Aragon served in the Indian Ocean. In December 1916 she sailed from Kilindini Harbour in the British East Africa Protectorate, reaching Durban on Christmas Day.[27]

Alexandria Roads[edit]

Late in 1917 Aragon spent two weeks at anchor off Marseille before receiving orders in December to sail for Egypt.[5] She took about 2,200 troops[1] to reinforce the Egyptian Expeditionary Force in the Palestine Campaign against the Ottoman Empire, plus about 150 military officers, 160 VADs and about 2,500 bags of Christmas mail.[1] She and another transport, the Nile, then sailed in convoy with an escort of destroyers[5] for Egypt. On 23 December[5] they reached Windy Bay, Malta, where the two transports stayed at anchor for four[1][5] or five[28] days. There they celebrated Christmas, and according to one VAD those aboard Aragon had a "top hole" time.[28]

Aragon and Nile then continued to Egypt with a fresh escort: the Acheron-class destroyer HMS Attack plus two Imperial Japanese Navy destroyers.[1] The convoy weathered a gale,[29] and off the Egyptian coast at daybreak on Sunday 30 December it divided.[5] The two Japanese destroyers escorted Nile to Port Said, while Attack escorted Aragon to Alexandria.[5] On approach to the port Attack zig-zagged ahead to search the channel for mines while Aragon waited in Alexandria Roads.[21]

The armed trawler HMT Points Castle approached Aragon flying the international flag signal "Follow me". The troop ship did so, until Attack returned and signalled "You have no right to take orders from a trawler".[21] The destroyer intercepted Points Castle and then ordered Aragon to return to sea.[1][3] The troop ship obeyed and turned back to sea.[21]

The most senior of Aragon's officers to survive what followed tried to make sense of the confusion:

"The only explanation that the writer can put forward is that the commander of the Attack had a warning of mines in the channel, causing him to order Aragon to disregard Points Castle's "Follow me". Evidently the enemy laid mines at the appropriate time in the knowledge that the ship would be kept out and thus present a target for torpedo attack."[21]

Aragon and Attack were in Alexandria Roads[30] about 8 miles (13 km)[5] or 10 miles (16 km) outside the port, awaiting permission to enter, when at about 1100 hrs[5] the German Type UC II submarine SM UC-34 torpedoed Aragon,[1][3] hitting her port side aft[1] and causing extensive damage in her almost empty number 4 hold.[21][28] Aragon's deck officer of the watch, Lieut. J.F.A. Thompson, stated that she then listed to starboard.[5]

Rescue[edit]

Let us take our chance with the Tommies.

— A VAD, quoted in The Northern Star, 8 April 1918

Attack and Points Castle came to the rescue.[1][3] One account states that two trawlers were present.[29] The VADs were ordered into the first lifeboats to be launched.[28][31] Two or three of the VADs protested at being given priority and one pleaded "Let us take our chance with the Tommies" before they all obeyed orders.[31] The VADs' boats rescued some troops from the water[28] and then transferred their survivors to one[29] or two[29] trawlers. Aragon released her life rafts[5] but the explosion had smashed one of her lifeboats[31] and her increasing list prevented her crew from launching some of the remainder.[5] Aragon's crew worked until they were waist deep in water to launch what boats they could.[31]

I have heard the chorus Keep the Home Fires Burning on many occasions but I don't think that I have ever heard it given with so much power.

— A survivor, quoted in The Northern Star, 8 April 1918

Attack drew right alongside Aragon to take survivors aboard as quickly as possible,[29] helped by lines cast between the two ships.[5] The troop ship sank rapidly by the stern.[5][29] More than one survivor stated that soldiers waiting on deck to be rescued started singing.[28] One said "I have heard the chorus 'Keep the Home Fires Burning' on many occasions but I don't think that I have ever heard it given with so much power".[31]

By now there was an increasing number of men in the water, and trooper James Werner Magnusson of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles saw an injured soldier struggling in the very rough sea.[32] He dived overboard from the ship, rescued the man and placed him in a boat.[32] Magnusson then returned aboard, rejoined his unit, and went down with the ship.[32] He was posthumously awarded the Albert Medal.[32]

A draft of 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, Buffs (East Kent Regiment) sent to reinforce the 10th (Royal East Kent and West Kent Yeomanry) Battalion, Buffs, won high praise for its discipline. First, Lance-Sergeant Canfor (himself injured by the explosion) called the roll, then men were detailed to cut away the life rafts while the rest sang. When the rafts were launched Lance-Corporal Baker volunteered to jump into the water to secure a life raft that was drifting away, assuring the safety of about 20 men. The rest of the draft then entered the water and clung onto the rafts for two and a half hours, singing and cheering on the rescue efforts. Only one man of the draft was lost.[33]

We felt that all our friends were drowning before our eyes.

— A VAD, quoted in MacDonald 1984, pp. 230–231

About 15 minutes[5] after the torpedo struck Aragon, her Master, Captain Bateman, gave the order from her bridge "Every man for himself".[31] Those remaining aboard rushed to get over her side,[5] and her bow rose out of the sea as soldiers swarmed down her side into the water.[29] One of the VADs who survived later recorded "We felt that all our friends were drowning before our eyes".[29] About 17[28] to 20 minutes after being hit Aragon went down, and she suffered a second explosion as the cold seawater reached her hot boilers.[5] Some of her boats were left upturned in the water.[5]

Attack was now crowded with 300 to 400 survivors:[31] some naked, some wounded, many unconscious and dying.[29] One soldier, Sergeant Harold Riddlesworth of the Cheshire Regiment, repeatedly dived from the destroyer into the sea to rescue more survivors.[34] He survived and was decorated with the Meritorious Service Medal.[34][35]

Then a torpedo struck Attack amidships and blew her into two pieces,[28] both of which sank with five to seven minutes.[5] The explosion ruptured Attack's bunkers, spilling tons of thick, black bunker fuel oil into the sea as she sank.[29] Hundreds of men were in the water, and many of them became covered in oil or overcome by its fumes.[29]

Aragon's surviving lifeboats now ferried hundreds of survivors to the trawlers, where the VADs "worked unceasingly and with great heroism" to tend the many wounded.[5] Other trawlers came out to assist,[5] and the first trawler or trawlers[5] returned to harbour for safety.[29]

Deaths and survivors[edit]

Of those aboard Aragon, 610 were killed[1][3] including Captain Bateman, 19 of his crew,[3] and six of the VADs.[29] Hundreds of troops were killed. One was Ernest Horlock, a Royal Field Artillery Battery Sergeant Major who had received the VC for "conspicuous gallantry" shown on the Western Front in 1914.[29] Private Fred J. Barnes, a Essex Regiment soldier who had worked as a songwriter before the war, also died.[36] Airman 2nd Class Alfred Moore who died age 22 from Lower Edmonton, London. Another 25 of those killed were new recruits to the 5th Battalion the Bedfordshire Regiment.[37] Soldiers killed in the sinking are among those commemorated by the Chatby Memorial in the Shatby district of eastern Alexandria.[38]

Aragon's second officer was among the survivors.[39] A month later he told the Master of an Australian troopship, the converted AUSNC liner HMAT Indarra, that as Aragon sank Captain Bateman shouted from her bridge to Attack's commander that he would demand an enquiry into his ship having been ordered out of port.[39] Bateman then jumped overboard and was not seen again.[39]

Many of the survivors from Aragon's crew were repatriated to England, reaching Southampton on 10 February 1918.[31] Some voyaged all the way by steamship, but the majority travelled overland.[31]

Wreck[edit]

Aragon remains a wreck off the Egyptian coast, lying in about 40 metres (130 ft) of water.[1]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Aragon". North Coast Shipwrecks. Shipwrecks of Egypt. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d Seligmann 2012, p. 144

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Lettens, Jan (9 November 2009). "SS Aragon [+1917]". The Wreck Site. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Seligmann 2012, p. 132

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad "1914–1926". Royal Mail Steam Packet Company. Merchant Navy Officers. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ a b c "Aragon". Shipping and Shipbuilding. Shipping and Shipbuilding Research Trust. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Royal Mail to Plate". Ships-Worldwide.com. Trains-WorldExpresses.com. 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "Aragon". Harland and Wolff. Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- ^ Nicol 2001, p. 99.

- ^ a b c Nicol 2001, p. 101.

- ^ Sivell, Jay (22 April 2010). "6. Great steamers white and gold". A sailor's life. WordPress. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ a b Nicol 2001, p. 104.

- ^ Registrar General of Shipping and Seamen (1906). Mercantile Navy List. Board of Trade. p. 23. Retrieved 19 January 2021 – via Crew List Index Project.

- ^ Nicol 2001, p. 100.

- ^ Nicol 2001, p. 106.

- ^ The Marconi Press Agency Ltd 1913, p. 245.

- ^ Seligmann 2012, p. 136.

- ^ Seligmann 2012, p. 139.

- ^ a b c Seligmann 2012, p. 141.

- ^ Seligmann 2012, p. 145.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nicol 2001, p. 117.

- ^ a b Scully, Louis (2002–2012). "4th Battalion Worcestershire Regiment - 1915". The Worcestershire Regiment – The History of the Regiment 1694 – 1970. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ a b c "White, Frederick". Hurst War Memorial. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Report of the Meeting of 20th – 22nd July 2012 York Weekend 60th Anniversary Conference". Forces Postal History Society. July 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ a b Clegg, Jack (2000–2012). "1st Royal Marine Battalion (aka 1st Bn. RMLI) War Diaries: May 1916 to Jan. 1919". The Campaign for War Grave Commemorations. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ a b Clegg, Jack (2000–2012). "Royal Naval Division War Diary Jan. to May 1916". The Campaign for War Grave Commemorations. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ Grice, Rob (September 2009). "East London's Edkins brothers in WWI". The South African Military History Society. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jones, Maureen (November 2007). "Poems of the First World War". The War Poetry Web Site. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n MacDonald 1984, pp. 230–231

- ^ Helgason, Guðmundur. "Ships hit during WWI: Aragon". German and Austrian U-boats of World War I - Kaiserliche Marine - Uboat.net. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Last Song on Doomed Ship". The Northern Star. Lismore, New South Wales. 8 April 1918. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Board of Trade, Whitehall Gardens, 7th March, 1918". The London Gazette. 8 March 1918. p. 229. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ Moody, pp. 64–5.

- ^ a b "Amazing tale of 'luckiest soldier'". Macclesfield Express. Trinity Mirror. 20 July 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "His Majesty the KING has been graciously pleased to approve the award of the Meritorious Service Medal to the undermentioned". The London Gazette. 8 March 1918. p. 5037. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "Casualty Details: F J Barnes". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ Fuller, Steven (2003–2013). "The sinking of the S.S. Aragon, 30th December 1917". The Bedfordshire Regiment in the Great War. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ "Chatby Memorial". Cemetery details. Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ a b c Thompson 1918, pp. 20–21

Sources and further reading[edit]

- MacDonald, Lyn (1984) [1980]. The Roses of No Man's Land (2nd ed.). Harmondsworth: Papermac. ISBN 014017866X.

- The Marconi Press Agency Ltd (1913). The Year Book of Wireless Telegraphy and Telephony. London: The St Katherine Press.

- Col R.S.H. Moody, Historical Records of The Buffs, East Kent Regiment, 1914–1919, London: Medici Society, 1922/Uckfield, Naval & Military Press, 2002, ISBN 978-1-84342395-9.

- Nicol, Stuart (2001). MacQueen's Legacy; Ships of the Royal Mail Line. Vol. Two. Brimscombe Port and Charleston, SC: Tempus Publishing. pp. 101–105, 117–118. ISBN 0-7524-2119-0.

- Seligmann, Matthew S (2012). The Royal Navy and the German Threat 1901 – 1914: Admiralty Plans to Protect British Trade in a War Against Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-19-957403-2.

- Thompson, JEM (13 October 1917 – 29 October 1918). Diary. State Library of New South Wales. MLMSS 2889/Item 1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

External links[edit]

- RMS Aragon Short video with numerous interior images of the ship

- Rawlins, John. "John Pugh". Machen First World War Memorial Site. — memorial to a Royal Engineers sapper, illustrated with Imperial War Museum photographs of Aragon in service and sinking

- "HAMILTON: 7/4/1-42 Instructions, reports, orders of battle, staff diary and related papers of General Headquarters, Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, 1915". Catalogues. King's College London. Retrieved 9 April 2013. — catalogue of military documents dating from 9 July 1915 to 8 May 1916 about Aragon's part in the Gallipoli Campaign.

4147400315463578 31°18′N 29°48′E / 31.300°N 29.800°E

- 1905 ships

- Maritime incidents in 1917

- Maritime incidents in Egypt

- Ships built by Harland and Wolff

- Ships built in Belfast

- Ships of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company

- Ships sunk by German submarines in World War I

- World War I shipwrecks in the Mediterranean Sea

- Steamships of the United Kingdom

- World War I passenger ships of the United Kingdom