Hans Sachs (poster collector)

Hans Sachs (1881-1974) was a Berlin dentist whose greatest accomplishment came from his passion for posters. He was the leading founder of an important group devoted to collecting posters which started an influential poster magazine. Before the seizure of his collection of 12,500 posters during Kristallnacht on 9 November 1938, he had the largest collection of posters in Germany, probably in the world. He was able to escape to the United States, but he never regained possession of the posters. After years of court battles, 4,344 posters were returned to his son in 2013. Some will be given to museums, but most have been or will be sold at auction.

His life in Germany[edit]

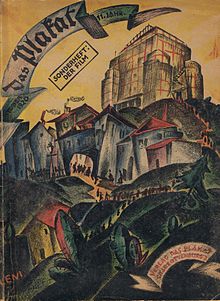

Hans Josef Sachs was born in Breslau, Germany, now Wrocław, Poland, on 11 August 1881.[1] He began collecting posters when he was only 16, possibly inspired by a gift to his father of three life-size prints of Sarah Bernhardt signed by Alphonse Mucha. In 1903-4 he served a year in the army, and again for some months in 1914–15. He was educated as a chemist, receiving his doctorate in 1904 in chemistry, physics, and mathematics; and then another in dentistry.[2] He then interned for six months in the United States.[3] He was married for the first time in 1910. While he was successful as a dentist, with Albert Einstein among his patients, and wrote a number of standard works on periodontosis, his avocation was posters.[2][4] He regularly worked from three o'clock in the afternoon into the night on his passion, making a detailed index card for each poster, each of which was identified by a numbered label. His poster collection grew, and in 1905 he was one of the principal founders and then the president of the Verein der Plakatfreunde (Society of Poster Friends), which soon had regional chapters. In 1910 it founded a quarterly Das Plakat (The Poster), with Sachs as both editor and publisher.[2]

The purpose of Das Plakat was to promote poster art, for both collectors and scholars. While there were a number of magazines devoted to posters, of Das Plakat it was said "And the clarion of this German poster exuberance was a magazine called Das Plakat, which not only exhibited the finest poster examples from Germany and other European countries, but its high standards underscored its exquisite printing, established qualitative criteria that defined the decade of graphic design between 1910 and 1920."[3] Moreover, "given its focus on conventional and avant garde sensibilities (it) emerged as a more historically influential review than any of the others".[5] During its short life from 1910 to 1921, its circulation grew from 200 to over 10,000. The Verein der Plakatfreunde ended a year later. It is unclear why the poster group and its magazine ended, possibly because of conflicts between collectors, art lovers, commercial artists, and business.[3]

After the war, he was appointed to a panel charged with selecting designs for postage stamps for the new Weimar Republic, and to the board of film censorship. After the end of the group, he lost all interest in posters for two years. Then a fire broke out in his house in the room where they were kept, but the thick walls of their storage cabinets insulated the posters from damage. He hired a famous architect, Oskar Kaufmann, to design a small museum, a special room in his house to hold and display his posters. The room was almost finished when another fire broke out. It was rebuilt by the middle of 1926. Two years later, he moved, and rebuilt the museum in the new house. His love for the collection revived, and he added many new posters, worked on its catalog, and arranged lectures.[2]

The poster collection[edit]

The collection was not narrowly focused. Its 12,500 posters included works by world-famous artists such as Pierre Bonnard, Wassily Kandinsky, Käthe Kollwitz, Edvard Munch , and 31 of the 35 posters designed by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. There were posters by the Viennese Secessionists Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Joseph Maria Olbrich, and the Munich Secessionist Franz Stuck; and Art Nouveau and Jugendstil posters by Aubrey Beardsley, Thomas Theodor Heine, Alphonse Mucha, and Henry van de Velde. Famous Plakatstil (Posterstyle) artists included Edmund Edel, Hans Rudi Erdt, Julius Gipkens, Ludwig Hohlwein, Julius Klinger, Hans Lindenstadt, Paul Scheurich,Karl Schulpig, and Lucian Zabel . Others were by Continental leaders in graphic design and posters Lucian Bernhard, Jules Chéret, Max Pechstein, Théophile Steinlen, and Félix Vallotton, joined with works by famous American artists James Montgomery Flagg, Charles Dana Gibson, Maxfield Parrish, and Edward Penfield.[6][7][8]

Arrest, escape from Germany and life in America[edit]

On 9 November 1938, Kristallnacht, he was arrested and sent to the Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg concentration camp. The collection was stolen by order of Joseph Goebbels, who wanted them for a proposed new wing devoted to business art in the Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin (Museum of Decorative Arts). After 17 days in the concentration camp, Sachs was released, and with his second wife Felicia and their one-year-old son Peter were able to escape from Germany, first to London for a few days, and then to New York. From his former collection he was able to take with him only the 31 posters by Toulouse-Lautrec, which he later sold in America.[2] Despite a recommendation from his former patient in Berlin, Albert Einstein, that he was well qualified to practice dentistry, he had to return to school, getting a second doctorate in dentistry from the Harvard School of Dental Medicine in 1941.[1][6]

In the 1950s, he was told by the West German government that the posters had been destroyed by the Russians. In 1961 he accepted compensation of about 225,000 marks, then about $25,000.[9] But in 1966, many were rediscovered in East Berlin, in the basement of the Deutsches Historisches Museum (German Historical Museum). Sachs's posters were identified by his label affixed to the back.[4] Although Sachs flew to Berlin in 1974, he was not allowed to enter East Berlin. He died that year on March 21 without seeing his posters again.[6][10]

Later history[edit]

After seven years in the courts, in February 2009, Hans Sachs's son Peter was ruled to be the lawful owner of 4,344 posters, but it was not until 2013 that they were released.[11] Guernsey's auction house in New York held sales in January and November 2013, and will hold a third on a date not yet announced. Buyers included the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Peter Sachs died in September 2013.[12][13]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Mock, Wanda. "Assistant Dean for Development and Alumni Relations, Harvard School of Dental Medicine (email, 28 July 2014)".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ a b c d e Sachs, Hans J., Ph.D., D.M.D. (January 2013). 'The World's Largest Poster Collection', January, 1957, reprinted in The Hans Sachs Poster Collection, Part I. New York: Guernsey's (auction house). pp. 7–29.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Heller, Steven (2004) [Spring 1999]. "Graphic Design Magazines: Das Plakat". Graphic Design Magazines. 25 (4). Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ a b Kohlenberg, Kerstin (15 January 2009). "In the name of my father" (PDF). Die Zeit (English edition). Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ Heller, Steven (14 November 2008). "History of Aggressive Design Magazines". Design Observer, the Design Observer Group. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ a b c Glass, Suzanne (28 January 2010). "Will posters confiscated by Nazis from Einstein's dentist be returned?" (PDF). The Times (London). Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ Artist Index, The Hans Sachs Poster Collection, Part I. New York: Guernsey's auction house. January 2013. pp. 242–4.

- ^ Artist Index, The Hans Sachs Poster Collection, Part II. New York: Guernsey's auction house. November 2013. pp. 228–9.

- ^ Hickley, Catherine (16 March 2012). "Nazi-Looted Posters Must Return to Sachs Heir, Court Rules". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ "German Museum Denies Heir Art Collection Stolen By Nazis". www.lootedart.com. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ^ Rising, David. "Hans Sachs Posters Seized By Nazis In 1938 Back In Family's Possession". HuffPost. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ "Jewish Museum of Florida-FIU to Debut Dr. Hans Sachs Poster Collection, Seized by Nazis in 1938". Jewish Museum of Florida – FIU. 6 June 2013. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ Kahn, Eve M. (12 October 2013). "Posters Lost to Nazis Are Recovered, and Up for Sale". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

Further reading[edit]

- Martijn F. Le Coultre, René Grohnert, Bernhard Denscher, Robert K. Brown, Suzanne Glass. Hans Sachs and the Poster Revolution. Stichting het ReclameArsenaal. 2013, ISBN 978-90-774-02-009

External links[edit]

Media related to Hans Sachs collection at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hans Sachs collection at Wikimedia Commons