Heat Shield Rock

| Heat Shield Rock | |

|---|---|

Heat Shield Rock | |

| Type | Iron |

| Group | Probably IAB |

| Composition | 93% Iron, 7% nickel, trace of germanium (~300 ppm) & gallium (<100 ppm) |

| Region | Meridiani Planum |

| Coordinates | 1°54′S 354°30′E / 1.9°S 354.5°E |

| Observed fall | No |

| Found date | January 2005 |

| Alternative names | Meridiani Planum meteorite |

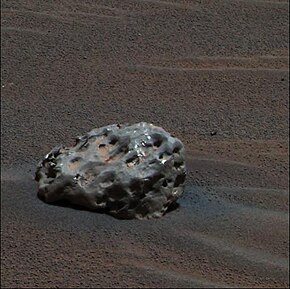

Heat Shield Rock is a basketball-sized iron-nickel meteorite found on the Meridiani Planum plain of Mars by the Mars rover Opportunity in January 2005.

Informally referred to as "Heat Shield Rock" by the Opportunity research team, the meteorite was formally named Meridiani Planum meteorite by the Meteoritical Society in October 2005 (meteorites are always named after the place where they were found).[1]

Discovery

Opportunity encountered the meteorite entirely by chance, in the vicinity of its own discarded heat shield (hence the name). Opportunity had been sent to examine the heat shield after exiting the crater Endurance. This was the first meteorite found on another planet and the third found on another Solar System body – two others, the millimeter-sized Bench Crater and Hadley Rille meteorites, were found on the Moon.

Analysis

The rock was initially identified as unusual in that it showed, from the analysis with the Mini-TES spectrometer, an infrared spectrum that appeared unusually similar to a reflection of the sky. In-situ measurements of its composition were then made using the APXS, showing the composition to be 93% Iron, 7% nickel, with trace amounts of germanium (~300 ppm) and gallium (<100 ppm). Mössbauer spectra show the iron to be primarily in metallic form, confirming its identity as an iron-nickel meteorite, composed of kamacite with 5–7% nickel. This is essentially identical to the composition of a typical IAB iron meteorite found on Earth. The surface of the rock shows the regmaglypts, or pits formed by the ablation of a meteorite during passage through the atmosphere, characteristic of meteorites. The largest dimension of the rock is nearing 31 cm.[2]

No attempt was made to drill into the meteorite using the Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT), because testing on iron meteorites on Earth showed that the rover's drilling tools would be abraded and damaged. The RAT was designed to drill into ordinary rock, not into iron-nickel alloy. Meridiani Planum, the part of Mars where this meteorite was found, is suspected to have once been covered by a layer of material with a thickness of as much as 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) which has been subsequently eroded. However no evidence suggests when it impacted. To survive impact largely undeformed it must have impacted at less than ~1.5 km/s, which sets boundaries on its entry dynamics and Mars' atmosphere at the time it impacted. In any case, the meteorite did not show much sign of rust. In the absence of detailed knowledge of the Mars environment, it is not possible to conclude whether it fell recently or not.[citation needed]

Other nickel-iron meteorites found on Mars

Following the identification of Heat Shield Rock as a meteorite, five similar iron meteorites were discovered by Opportunity (informally named "Block Island", "Ireland"[2] "Mackinac Island", "Oileán Ruaidh" and "Shelter island"). Two nickel-iron meteorites were identified by the Spirit rover (informally named "Allan Hills" and "Zhong Shan"). One nickel-iron meteorite has been identified by the Curiosity rover, tagged "Lebanon."[3] In addition, several candidate stony meteorites have also been identified on Mars.

Terminology

The term "Martian meteorite" usually refers to something entirely different: meteorites on Earth which are believed to have originated from Mars,[4] a famous example being ALH84001.[5]

Gallery

See also

- Atmospheric entry – Passage of an object through the gases of an atmosphere from outer space

- Block Island meteorite – Iron meteorite on Mars

- Bounce Rock – Football-sized primarily pyroxene rock found in the Margaritifer Sinus quadrangle of Mars

- Glossary of meteoritics

- List of Martian meteorites

- List of rocks on Mars – Alphabetical list of named rocks and meteorites found on Mars

- Mackinac Island meteorite – Martian meteorite

- Oileán Ruaidh meteorite – Meteorite found on Mars

- Shelter Island meteorite – Meteorite on Mars

References

- ^ The Meteoritical Society, Guidelines For Meteorite Nomenclature, 2.2 Distinctive names [1]

- ^ a b Fairén, A. G.; Dohm, J. M.; Baker, V. R.; Thompson, S. D.; Mahaney, W. C.; Herkenhoff, K. E.; Rodríguez, J. A. P.; Davila, A. F.; et al. (December 2011). "Meteorites at Meridiani Planum provide evidence for significant amounts of surface and near-surface water on early Mars". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 46 (12): 1832–1841. Bibcode:2011M&PS...46.1832F. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.2011.01297.x.

- ^ NASA, Curiosity Finds Iron Meteorite on Mars, July 15, 2014 (accessed September 3, 2014)

- ^ "Mars Meteorites". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- ^ "Meteoritical Bulletin Database: Allan Hills 84001".

Further reading

- D. S. Rodionov, et al., "An Iron-Nickel Meteorite on Meridiani Planum: Observations by MER Opportunity’s Mössbauer Spectrometer," European Geosciences Union; Geophysical Research Abstracts, Vol. 7, 10242; 1607-7962/gra/EGU05-A-10242 (2005).

- Christian Schröder, et al., "Meteorites on Mars observed with the Mars Exploration Rovers," Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, v. 113(E6), E06S22, doi:10.1029/2007JE002990 (2008).

- A. S. Yen, et al., "Nickel on Mars: Constraints on Meteoritic Material at the Surface," Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, v. 111, E12S11, doi:10.1029/2006JE002797 (2006).

- G. A. Landis, "Meteoric Steel as a Construction Resource on Mars,", Acta Astronautica, Vol. 64, No. 2–3 (Jan–Feb. 2009). Presented at the Ninth Space Resources Roundtable, Colorado School of Mines, October 2007 presentation, 5.9 mb (powerpoint)

External links

- Nasa's Mars Exploration Program

- NASA announcement

- NAA Opportunity Archive: sol-by-sol account of the program and the discovery of Heat Shield Rock

- JPL meteorite image

- JPL Photojournal entry on meteorite

- Sky & Telescope article

- Space.com article

- Article in Meteoritical Bulletin

- Official Mars Rovers site

- Meteorites Found on Mars Planetary Science Research Discoveries article.