Hip hop (culture): Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 108.162.147.166 to version by Sgr927. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (0) (Bot) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

In the 1970s an underground urban movement known as "hip hop" began to develop in the South Bronx area of [[New York City]] focusing on [[emceeing]] (or MCing), [[breakbeat]]s, and [[house party|house parties]]. Starting at the home of [[DJ Kool Herc]] at the high-rise apartment at [[1520 Sedgwick Avenue]], the movement later spread across the entire borough. Rap developed both inside and outside of hip hop culture, and began in America in earnest with the street parties thrown in the Bronx neighborhood of New York in the 1970s by [[Kool Herc]] and others—[[Jamaican]] born DJ Clive "[[Kool Herc]]" Campbell is credited as being highly influential in the pioneering stage of hip hop music,<ref>{{cite news|last=Hermes|first=Will|title=All Rise for the National Anthem of Hip-Hop|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/29/arts/music/29herm.html?_r=1|accessdate=29 March 2012|newspaper=New York Times|date=October 29, 2006}}</ref> Herc created the blueprint for hip hop music and culture by building upon the Jamaican tradition of impromptu [[Deejay (Jamaican)|toasting]], boastful poetry and speech over music.<ref>{{Harvnb|Campbell|Chang|2005|p=??}}.</ref> |

In the 1970s an underground urban movement known as "hip hop" began to develop in the South Bronx area of [[New York City]] focusing on [[emceeing]] (or MCing), [[breakbeat]]s, and [[house party|house parties]]. Starting at the home of [[DJ Kool Herc]] at the high-rise apartment at [[1520 Sedgwick Avenue]], the movement later spread across the entire borough. Rap developed both inside and outside of hip hop culture, and began in America in earnest with the street parties thrown in the Bronx neighborhood of New York in the 1970s by [[Kool Herc]] and others—[[Jamaican]] born DJ Clive "[[Kool Herc]]" Campbell is credited as being highly influential in the pioneering stage of hip hop music,<ref>{{cite news|last=Hermes|first=Will|title=All Rise for the National Anthem of Hip-Hop|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/29/arts/music/29herm.html?_r=1|accessdate=29 March 2012|newspaper=New York Times|date=October 29, 2006}}</ref> Herc created the blueprint for hip hop music and culture by building upon the Jamaican tradition of impromptu [[Deejay (Jamaican)|toasting]], boastful poetry and speech over music.<ref>{{Harvnb|Campbell|Chang|2005|p=??}}.</ref> |

||

This became [[Emceeing]] - the rhythmic spoken delivery of [[rhyme]]s and wordplay, delivered over a [[beats (music)|beat]] or without accompaniment—taking inspiration from the [[Rapping]] derived from the [[griot]]s (folk poets) of [[African music|West Africa]], and [[Jamaican music|Jamaican]]-style [[Deejay (Jamaican)|toasting]]. The basic elements of [[hip-hop]]—boasting raps, rival posses, uptown throwdowns, and political commentary—were all present in [[Music of Trinidad & Tobago|Trinidadan music]] as long ago as the 1800's, though they did not reach the form of commercial recordings until the 1920's and 30's. [[Calypso music]]—like other forms of music—continued to evolve through the '50's and '60's. When [[rock steady]] and [[reggae]] bands looked to make their music a form of national and even international Black resistance, they took Calypso's example. Calypso itself, like Jamaican music, moved back and forth between the predominance of boasting and toasting songs packed with 'slackness' and sexual innuendo and a more topical, political, 'conscious' style. |

This became [[Emceeing]] - the rhythmic spoken delivery of [[rhyme]]s and wordplay, delivered over a [[beats (music)|beat]] or without accompaniment—taking inspiration from the [[Rapping]] derived from the [[griot]]s (folk poets) of [[African music|West Africa]], and [[Jamaican music|Jamaican]]-style [[Deejay (Jamaican)|toasting]]. The basic elements of [[hip-hop]]—boasting raps, rival posses, uptown throwdowns, and political commentary—were all present in [[Music of Trinidad & Tobago|Trinidadan music]] as long ago as the 1800's, though they did not fluffy unicorns are cool,''" reach the form of commercial recordings until the 1920's and 30's. [[Calypso music]]—like other forms of music—continued to evolve through the '50's and '60's. When [[rock steady]] and [[reggae]] bands looked to make their music a form of national and even international Black resistance, they took Calypso's example. Calypso itself, like Jamaican music, moved back and forth between the predominance of boasting and toasting songs packed with 'slackness' and sexual innuendo and a more topical, political, 'conscious' style. |

||

[[Melle Mel]], a rapper/lyricist with The [[Furious Five]], is often credited with being the first rap lyricist to call himself an "MC".<ref>[http://www.allhiphop.com/features/?ID=1686 Article about MelleMel (Melle Mel) at AllHipHop.com]{{Dead link|date=April 2010}}</ref> |

[[Melle Mel]], a rapper/lyricist with The [[Furious Five]], is often credited with being the first rap lyricist to call himself an "MC".<ref>[http://www.allhiphop.com/features/?ID=1686 Article about MelleMel (Melle Mel) at AllHipHop.com]{{Dead link|date=April 2010}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 19:53, 24 October 2013

Hip hop is a broad conglomerate of artistic forms that originated within a marginalized subculture in the South Bronx during the 1970s in New York City.[1][2][3][4][5][6] It is characterized by four distinct elements, all of which represent the different manifestations of the culture: rap music (oral), turntablism or "DJing" (aural), breaking (physical) and graffiti art (visual). Despite their contrasting methods of execution, they find unity in their common association to the poverty and violence underlying the historical context that birthed the culture. It was as a means of providing a reactionary outlet from such urban hardship that "Hip Hop" initially functioned, a form of self-expression that could reflect upon, proclaim an alternative to, try and challenge or merely evoke the mood of the circumstances of such an environment. Even while it continues in contemporary history to develop globally in a flourishing myriad of diverse styles, these foundational elements provide stability and coherence to the culture.[1] The term is frequently used mistakenly to refer in a confining fashion to the mere practice of rap music.

The origin of the culture stems from the block parties of the Ghetto Brothers when they would plug the amps for their instruments and speakers into the lampposts on 163rd Street and Prospect Avenue and DJ Kool Herc at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, where Herc would mix samples of existing records with his own shouts to the crowd and dancers. Kool Herc is credited as the "father" of Hip hop. DJ Afrika Bambaataa of the hip hop collective Zulu Nation outlined the pillars of hip hop culture, to which he coined the terms: MCing, DJing, B-boying and graffiti writing.[7][8][9][10][11]

Since its evolution throughout the South Bronx, hip hop culture has spread to both urban and suburban communities throughout the world.[12] Hip hop music first emerged with Kool Herc and contemporary disc jockeys and imitators creating rhythmic beats by looping breaks (small portions of songs emphasizing a percussive pattern) on two turntables. This was later accompanied by "rap", a rhythmic style of chanting or poetry often presented in 16-bar measures or time frames, and beatboxing, a vocal technique mainly used to provide percussive elements of music and various technical effects of hip hop DJs. An original form of dancing and particular styles of dress arose among fans of this new music. These elements experienced considerable adaptation and development over the course of the history of the culture.

Hip hop is simultaneously a new and old phenomenon; the importance of sampling to the art form means that much of the culture has revolved around the idea of updating classic recordings, attitudes, and experiences for modern audiences—called "flipping" within the culture. It follows in the footsteps of earlier American musical genres blues, salsa, jazz, and rock and roll in having become one of the most practiced genres of music in existence worldwide, and also takes additional inspiration regularly from soul music, funk, and rhythm and blues.

Etymology

Hip hop is the combination of two separate slang terms—"hip", used in African American English as early as 1898, meaning current or in the now, and "hop", for the hopping movement.[citation needed]

Keith "Cowboy" Wiggins, a member of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, has been credited with coining the term[13] in 1978 while teasing a friend who had just joined the US Army, by scat singing the words "hip/hop/hip/hop" in a way that mimicked the rhythmic cadence of marching soldiers.[citation needed] Cowboy later worked the "hip hop" cadence into his stage performance.[14] The group frequently performed with disco artists who would refer to this new type of music by calling them "hip hoppers". The name was originally meant as a sign of disrespect, but soon came to identify this new music and culture.

The song "Rapper's Delight" by The Sugarhill Gang, released in 1979, begins with the scat phrase, "I said a hip, hop the hippie the hippie to the hip hip hop, a you don't stop." Lovebug Starski, a Bronx DJ who put out a single called "The Positive Life" in 1981, and DJ Hollywood then began using the term when referring to this new disco rap music. Hip hop pioneer and South Bronx community leader Afrika Bambaataa also credits Lovebug Starski as the first to use the term "Hip Hop", as it relates to the culture. Bambaataa, former leader of the Black Spades gang, also did much to further popularize the term. The words "hip hop" first appeared in print on September 21, 1981, in the Village Voice in a profile of Bambaataa written by Steven Hager, who also published the first comprehensive history of the culture with St. Martins' Press.[14][15][16]

History

In the 1970s an underground urban movement known as "hip hop" began to develop in the South Bronx area of New York City focusing on emceeing (or MCing), breakbeats, and house parties. Starting at the home of DJ Kool Herc at the high-rise apartment at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, the movement later spread across the entire borough. Rap developed both inside and outside of hip hop culture, and began in America in earnest with the street parties thrown in the Bronx neighborhood of New York in the 1970s by Kool Herc and others—Jamaican born DJ Clive "Kool Herc" Campbell is credited as being highly influential in the pioneering stage of hip hop music,[17] Herc created the blueprint for hip hop music and culture by building upon the Jamaican tradition of impromptu toasting, boastful poetry and speech over music.[18]

This became Emceeing - the rhythmic spoken delivery of rhymes and wordplay, delivered over a beat or without accompaniment—taking inspiration from the Rapping derived from the griots (folk poets) of West Africa, and Jamaican-style toasting. The basic elements of hip-hop—boasting raps, rival posses, uptown throwdowns, and political commentary—were all present in Trinidadan music as long ago as the 1800's, though they did not fluffy unicorns are cool," reach the form of commercial recordings until the 1920's and 30's. Calypso music—like other forms of music—continued to evolve through the '50's and '60's. When rock steady and reggae bands looked to make their music a form of national and even international Black resistance, they took Calypso's example. Calypso itself, like Jamaican music, moved back and forth between the predominance of boasting and toasting songs packed with 'slackness' and sexual innuendo and a more topical, political, 'conscious' style. Melle Mel, a rapper/lyricist with The Furious Five, is often credited with being the first rap lyricist to call himself an "MC".[19]

Herc also developed upon break-beat deejaying,[20] where the breaks of funk songs—the part most suited to dance, usually percussion-based—were isolated and repeated for the purpose of all-night dance parties. This form of music playback, using hard funk, rock, formed the basis of hip hop music. Campbell's announcements and exhortations to dancers would lead to the syncopated, rhymed spoken accompaniment now known as rapping. He dubbed his dancers break-boys and break-girls, or simply b-boys and b-girls. According to Herc, "breaking" was also street slang for "getting excited" and "acting energetically".[21]

DJs such as Grand Wizard Theodore, Grandmaster Flash, and Jazzy Jay refined and developed the use of breakbeats, including cutting and scratching.[22] The approach used by Herc was soon widely copied, and by the late 1970s DJs were releasing 12" records where they would rap to the beat. Popular tunes included Kurtis Blow's "The Breaks" and The Sugarhill Gang's "Rapper's Delight".[23] Herc and other DJs would connect their equipment to power lines and perform at venues such as public basketball courts and at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, Bronx, New York, now officially a historic building.[24] The equipment was composed of numerous speakers, turntables, and one or more microphones.[25] By using this technique DJs could create a variety of music, but according to Rap Attack by David Toop “At its worst the technique could turn the night into one endless and inevitably boring song”.[26] Nevertheless, the popularity of rap steadily increased.

Street gangs were prevalent in the poverty of the South Bronx, and much of the graffiti, rapping, and b-boying at these parties were all artistic variations on the competition and one-upmanship of street gangs. Sensing that gang members' often violent urges could be turned into creative ones, Afrika Bambaataa founded the Zulu Nation, a loose confederation of street-dance crews, graffiti artists, and rap musicians. By the late 1970s, the culture had gained media attention, with Billboard magazine printing an article titled "B Beats Bombarding Bronx", commenting on the local phenomenon and mentioning influential figures such as Kool Herc.[27]

In late 1979, Debbie Harry of Blondie took Nile Rodgers of Chic to such an event, as the main backing track used was the break from Chic's "Good Times".[23] The new style influenced Harry, and Blondie's later hit single from 1981 "Rapture" became the first major single containing hip hop elements by a white group or artist to hit number one on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100—the song itself is usually considered new wave and fuses heavy pop music elements, but there is an extended rap by Harry near the end.

Hip hop as a culture was further defined in 1982, when Afrika Bambaataa and the Soulsonic Force released the seminal electro-funk track "Planet Rock". Instead of simply rapping over disco beats, Bambaataa created an electronic sound, taking advantage of the rapidly improving drum machine Roland TB-303 synthesizer technology, as well as sampling from Kraftwerk.[28]

Encompassing graffiti art, mc'ing/rapping, DJing and b-boying, hip hop became the dominant cultural movement of the minority populated urban communities in the 1980s.[29] The 1980s also saw many artists make social statements through hip hop. In 1982, Melle Mel and Duke Bootee recorded "The Message" (officially credited to Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five),[30] a song that foreshadowed the socially conscious statements of Run-DMC's "It's like That" and Public Enemy's "Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos".[31] During the 1980s, hip hop also embraced the creation of rhythm by using the human body, via the vocal percussion technique of beatboxing. Pioneers such as Doug E. Fresh,[32] Biz Markie and Buffy from the Fat Boys made beats, rhythm, and musical sounds using their mouth, lips, tongue, voice, and other body parts. "Human Beatbox" artists would also sing or imitate turntablism scratching or other instrument sounds.

The appearance of music videos changed entertainment: they often glorified urban neighborhoods.[33] The music video for "Planet Rock" showcased the subculture of hip hop musicians, graffiti artists, and b-boys/b-girls. Many hip hop-related films were released between 1982 and 1985, among them Wild Style, Beat Street, Krush Groove, Breakin, and the documentary Style Wars. These films expanded the appeal of hip hop beyond the boundaries of New York. By 1985, youth worldwide were embracing the hip hop culture. The hip hop artwork and "slang" of US urban communities quickly found its way to Europe, as the culture's global appeal took root.

American society

DJ Kool Herc's house parties gained popularity and later moved to outdoor venues in order to accommodate more people. Hosted in parks, these outdoor parties became a means of expression and an outlet for teenagers, where "instead of getting into trouble on the streets, teens now had a place to expend their pent-up energy."[34]

Tony Tone, a member of the Cold Crush Brothers, noted that "hip hop saved a lot of lives".[34] Hip hop culture became a way of dealing with the hardships of life as minorities within America, and an outlet to deal with violence and gang culture. MC Kid Lucky mentions that "people used to break-dance against each other instead of fighting".[35][full citation needed] Inspired by DJ Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa created a street organization called Universal Zulu Nation, centered around hip hop, as a means to draw teenagers out of gang life and violence.[34]

The lyrical content of many early rap groups focused on social issues, most notably in the seminal track "The Message", which discussed the realities of life in the housing projects.[36] "Young black Americans coming out of the civil rights movement have used hip hop culture in the 1980s and 1990s to show the limitations of the movement."[37] Hip hop gave young African Americans a voice to let their issues be heard; "Like rock-and-roll, hip hop is vigorously opposed by conservatives because it romanticises violence, law-breaking, and gangs".[37] It also gave people a chance for financial gain by "reducing the rest of the world to consumers of its social concerns."[37]

However, with the commercial success of gangsta rap in the early 1990s, the emphasis shifted to drugs, violence, and misogyny. Early proponents of gangsta rap included groups and artists such as Ice-T, who recorded what some consider to be the first gangster rap record, 6 in the Mornin',[38] and N.W.A. whose second album Efil4zaggin became the first gangsta rap album to enter the charts at number one.[39] Gangsta rap also played an important part in hip hop becoming a mainstream commodity. The fact that albums such as N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton, Eazy-E’s Eazy-Duz-It, and Ice Cube's Amerikkka's Most Wanted were selling in such high numbers meant that black teens were no longer hip hop’s sole buying audience.[40]

As a result, gangsta rap became a platform for artists who chose to use their music to spread politic and social messages to parts of the country that were previously unaware of the conditions of ghettos.[38] While hip hop music now appeals to a broader demographic, media critics argue that socially and politically conscious hip hop has been largely disregarded by mainstream America.[41]

Global innovations

According to the U.S. Department of State, hip hop is "now the center of a mega music and fashion industry around the world," that crosses social barriers and cuts across racial lines.[42] National Geographic recognizes hip hop as "the world's favorite youth culture" in which "just about every country on the planet seems to have developed its own local rap scene."[43] Through its international travels, hip hop is now considered a “global musical epidemic”.[44]

According to The Village Voice, hip hop is “custom-made to combat the anomie that preys on adolescents wherever nobody knows their name.”[45]

Hip hop sounds and styles differ from region to region, but there are also instances of fusion genres.[46]

Not all countries have embraced hip hop, where "as can be expected in countries with strong local culture, the interloping wildstyle of hip hop is not always welcomed".[47] This is somewhat the case in Jamaica, the homeland of the culture's father, DJ Kool Herc. However, despite the fact that hip hop music produced on the island lacks widespread local and international recognition, artistes such as Five Steez have defied the odds by impressing online hip hop tastemakers and even reggae critics.[48]

Hartwig Vens argues that hip hop can also be viewed as a global learning experience.[49] Author Jeff Chang argues that "the essence of hip hop is the cipher, born in the Bronx, where competition and community feed each other."[50]

He also adds: "Thousands of organizers from Cape Town to Paris use hip hop in their communities to address environmental justice, policing and prisons, media justice, and education.".[51]

While hip hop music has been criticized as a music which creates a divide between western music and music from the rest of the world, a musical "cross pollination" has taken place, which strengthens the power of hip hop to influence different communities.[52] Hip hop's messages allow the under-privileged and the mistreated to be heard.[49] These cultural translations cross borders.[51] While the music may be from a foreign country, the message is something that many people can relate to- something not "foreign" at all.[53]

Even when hip hop is transplanted to other countries, it often retains its "vital progressive agenda that challenges the status quo."[51] In Gothenburg, Sweden, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) incorporate graffiti and dance to engage disaffected immigrant and working class youths.

Hip hop has played a small but distinct role as the musical face of revolution in the Arab Spring, one example being an anonymous Libyan musician, Ibn Thabit, whose anti-government songs fuel the rebellion.[54]

Commercialization

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (March 2009) |

A documentary called The Commodification of Hip Hop, directed by Brooke Daniel, interviews students at Satellite Academy in New York City. One girl talks about the epidemic of crime that she sees in urban minority communities, relating it directly to the hip hop industry, saying: “When they can’t afford these kind of things, these things that celebrities have like jewelry and clothes and all that, they’ll go and sell drugs, some people will steal it....”[55]

In an article for Village Voice, Greg Tate argues that the commercialization of hip hop is a negative and pervasive phenomenon, writing that "what we call hiphop is now inseparable from what we call the hip hop industry, in which the nouveau riche and the super-rich employers get richer".[37] Ironically, this commercialization coincides with a decline in rap sales and pressure from critics of the genre.[56] Even other musicians, like Nas and KRS-ONE have claimed "hip hop is dead" in that it has changed so much over the years to cater to the consumer that it has lost the essence for which it was originally created. However, in his book In Search Of Africa, Manthia Diawara explains that hip hop is really a voice of people who are down and out in modern society. He argues that the "worldwide spread of hip hop as a market revolution" is actually global "expression of poor people’s desire for the good life," and that this struggle aligns with "the nationalist struggle for citizenship and belonging, but also reveals the need to go beyond such struggles and celebrate the redemption of the black individual through tradition."

This connection to "tradition" however, is something that may be lacking according to one Satellite Academy staff member who says that in all of the focus on materialism, the hip hop community is “not leaving anything for the next generation, we’re not building. As the hip hop genre turns 30, a deeper analysis of the music’s impact is taking place. It has been viewed as a cultural sensation which changed the music industry around the world, but some believe commercialization and mass production have given it a darker side. Tate has described its recent manifestations as a marriage of “New World African ingenuity and that trick of the devil known as global-hypercapitalism”,[57] arguing it has joined the “mainstream that had once excluded its originators.”[57] While hip hop's values may have changed over time, the music continues to offer its followers and originators a shared identity which is instantly recognizable and much imitated around the world.

Culture

DJing

Turntablism is the technique of manipulating sounds and creating music using phonograph turntables and a DJ mixer.[58] One of the few first hip hop DJs was Kool DJ Herc, who created hip hop through the isolation of "breaks" (the parts of albums that focused solely on the beat). In addition to developing Herc's techniques, DJs Grandmaster Flowers, Grandmaster Flash, Grand Wizard Theodore, and Grandmaster Caz made further innovations with the introduction of scratching.

Traditionally, a DJ will use two turntables simultaneously. These are connected to a DJ mixer, an amplifier, speakers, and various other pieces of electronic music equipment. The DJ will then perform various tricks between the two albums currently in rotation using the above listed methods. The result is a unique sound created by the seemingly combined sound of two separate songs into one song. Although there is considerable overlap between the two roles, a DJ is not the same as a producer of a music track.[59]

In the early years of hip hop, the DJs were the stars, but that has been taken by MCs since 1978, thanks largely to Melle Mel of Grandmaster Flash's crew, the Furious Five. However, a number of DJs have gained stardom nonetheless in recent years. Famous DJs include Grandmaster Flash, Afrika Bambaataa, Mr. Magic, DJ Jazzy Jeff, DJ Scratch from EPMD, DJ Premier from Gang Starr, DJ Scott La Rock from Boogie Down Productions, DJ Pete Rock of Pete Rock & CL Smooth, DJ Muggs from Cypress Hill, Jam Master Jay from Run-DMC, Eric B., DJ Screw from the Screwed Up Click and the inventor of the Chopped & Screwed style of mixing music, Funkmaster Flex, Tony Touch, DJ Clue, Mix Master Mike and DJ Q-Bert. The underground movement of turntablism has also emerged to focus on the skills of the DJ.

MCing

Rapping (also known as emceeing,[60] MCing,[60] spitting (bars),[61] or just rhyming[62]) refers to "spoken or chanted rhyming lyrics with a strong rhythmic accompaniment".[63] It can be broken down into different components, such as “content”, “flow” (rhythm and rhyme), and “delivery”.[64] Rapping is distinct from spoken word poetry in that is it performed in time to the beat of the music.[65][66][67] The use of the word "rap" to describe quick and slangy speech or repartee long predates the musical form.[68] MCing is a form of expression that is embedded within ancient African culture and oral tradition as throughout history verbal acrobatics or jousting involving rhymes were common within the Afro-American community.[69]

Graffiti

In America around the late 1960s, graffiti was used as a form of expression by political activists, and also by gangs such as the Savage Skulls, La Familia, and Savage Nomads to mark territory. Towards the end of the 1960s, the signatures—tags—of Philadelphia graffiti writers Top Cat,[70] Cool Earl and Cornbread started to appear.[71] Around 1970–71, the center of graffiti innovation moved to New York City where writers following in the wake of TAKI 183 and Tracy 168 would add their street number to their nickname, "bomb" a train with their work, and let the subway take it—and their fame, if it was impressive, or simply pervasive, enough—"all city". Bubble lettering held sway initially among writers from the Bronx, though the elaborate Brooklyn style Tracy 168 dubbed "wildstyle" would come to define the art.[70][72] The early trendsetters were joined in the 1970s by artists like Dondi, Futura 2000, Daze, Blade, Lee, Fab Five Freddy, Zephyr, Rammellzee, Crash, Kel, NOC 167 and Lady Pink.[70]

The relationship between graffiti and hip hop culture arises both from early graffiti artists engaging in other aspects of hip hop culture,[73] Graffiti is understood as a visual expression of rap music, just as breaking is viewed as a physical expression. The 1983 film Wild Style is widely regarded as the first hip hop motion picture, which featured prominent figures within the New York graffiti scene during the said period. The book Subway Art and documentary Style Wars were also among the first ways the mainstream public were introduced to hip hop graffiti. Graffiti remains part of hip hop, while crossing into the mainstream art world with renowned exhibits in galleries throughout the world.

Breaking

In 1924, Earl Tucker (aka Snake Hips), a performer at the Cotton Club, created a dance style which would later inspire an element of hip hop culture known as b-boying.[74] Breaking, also called B-boying or breakdancing, is a dynamic style of dance which developed as part of the hip hop culture. Breaking is one of the major elements of hip hop culture. Like many aspects of hip hop culture, breakdance borrows heavily from many cultures, including 1930s-era street dancing,[75][76] Afro-Brazilian and Asian Martial arts, Russian folk dance,[77] and the dance moves of James Brown, Michael Jackson, and California Funk styles. Breaking took form in the South Bronx alongside the other elements of hip hop.

According to the 2002 documentary film The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, DJ Kool Herc describes the "B" in B-boy as short for breaking which at the time was slang for "going off", also one of the original names for the dance. However, early on the dance was known as the "boing" (the sound a spring makes). Dancers at DJ Kool Herc's parties, who saved their best dance moves for the break section of the song, getting in front of the audience to dance in a distinctive, frenetic style. The "B" in B-boy also stands simply for break, as in break-boy (or girl). Breaking was documented in Style Wars, and was later given more focus in fictional films such as Wild Style and Beat Street. Early acts include the Rock Steady Crew and New York City Breakers.

Beatbox

Beatboxing, popularized by Doug E. Fresh,[78] is the technique of vocal percussion. It is primarily concerned with the art of creating beats or rhythms using the human mouth.[79] The term beatboxing is derived from the mimicry of the first generation of drum machines, then known as beatboxes. As it is a way of creating hip hop music, it can be categorized under the production element of hip hop, though it does sometimes include a type of rapping intersected with the human-created beat. It is generally considered to be part of the same "Pillar" of hip hop as DJing—in other words, providing a musical backdrop or foundation for MC's to rhyme over.

Beatboxing was quite popular in the 1980s with prominent artists like the Darren "Buffy, the Human Beat Box" Robinson of the Fat Boys and Biz Markie displaying their skills within the media. It declined in popularity along with b-boying in the late 1980s, but has undergone a resurgence since the late 1990s, marked by the release of "Make the Music 2000." by Rahzel of The Roots.

Social impact

Effects

Hip hop has made a considerable social impact since its inception in the 1970s.[80] Orlando Patterson, a sociology professor at Harvard University helps describe the phenomenon of how hip hop spread rapidly around the world. Professor Patterson argues that mass communication is controlled by the wealthy, government, and businesses in Third World nations and countries around the world.[81] He also credits mass communication with creating a global cultural hip hop scene. As a result, the youth absorb and are influenced by the American hip hop scene and start their own form of hip hop. Patterson believes that revitalization of hip hop music will occur around the world as traditional values are mixed with American hip hop musical forms,[81] and ultimately a global exchange process will develop that brings youth around the world to listen to a common musical form known as hip hop. It has also been argued that rap music formed as a "cultural response to historic oppression and racism, a system for communication among black communities throughout the United States".[82] This is due to the fact that the culture reflected the social, economic and political realities of the disenfranchised youth.[83] In the Arab Spring hip hop played a significant role in providing a channel for the youth to express their ideas.[84]

Language

The development of hip hop linguistics is complex. Source material include the spirituals of slaves arriving in the new world, Jamaican dub music, the laments of jazz and blues singers, patterned cockney slang and radio deejays hyping their audience in rhyme.[85]

Hip hop has a distinctive associated slang.[86] It is also known by alternate names, such as "Black English", or "Ebonics". Academics suggest its development stems from a rejection of the racial hierarchy of language, which held "White English" as the superior form of educated speech.[87] Due to hip hop's commercial success in the late nineties and early 21st century, many of these words have been assimilated into the cultural discourse of several different dialects across America and the world and even to non-hip hop fans.[88] The word dis for example is particularly prolific. There are also a number of words which predate hip hop, but are often associated with the culture, with homie being a notable example.

Sometimes, terms like what the dilly, yo are popularized by a single song (in this case, "Put Your Hands Where My Eyes Could See" by Busta Rhymes) and are only used briefly. One particular example is the rule-based slang of Snoop Dogg and E-40, who add -izzle or -izz to the end or middle of words.

Hip hop lyricism has gained a measure of legitimacy in academic and literary circles. Studies of Hip hop linguistics are now offered at institutions such as the University of Toronto, where poet and author George Eliot Clarke has (in the past) taught the potential power of hip hop music to promote social change.[85] Greg Thomas of the University of Miami offers courses at both the undergraduate and graduate level studying the feminist and assertive nature of Lil' Kim's lyrics.[89]

Some academics, including Ernest Morrell and Jeffery Duncan Andrade compare hip hop to the satirical works of great “canon” poets of the modern era, who use imagery and mood to directly criticize society. As quoted in their seminal work, "Promoting Academic Literacy with Urban Youth Through Engaging Hip Hop Culture":

Hip hop texts are rich in imagery and metaphor and can be used to teach irony, tone, diction, and point of view. Hip hop texts can be analyzed for theme, motif, plot, and character development. Both Grand Master Flash and T.S. Eliot gazed out into their rapidly deteriorating societies and saw a "wasteland." Both poets were essentially apocalyptic in nature as they witnessed death, disease, and decay.[90]

Censorship

Hip hop has been met with significant problems in regards to censorship due to the explicit nature of certain genres, and some songs have been criticized for allegedly anti-establishment sentiment. For example, Public Enemy's "Gotta Give the Peeps What They Need" was censored on MTV, removing the words "free Mumia".[91]

After the attack on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, Oakland, California group The Coup was under fire for the cover art on their Party Music, which featured the group's two members holding a detonator as the Twin Towers exploded behind them despite the fact that it was created months before the actual event. The group, having politically radical and Marxist lyrical content, said the cover meant to symbolize the destruction of capitalism. Their record label pulled the album until a new cover could be designed.

The use of profanity as well as graphic depictions of violence and sex creates challenges in the broadcast of such material both on television stations such as MTV, in music video form, and on radio. As a result, many hip hop recordings are broadcast in censored form, with offending language "bleeped" or blanked out of the soundtrack, or replaced with "clean" lyrics. The result – which sometimes renders the remaining lyrics unintelligible or contradictory to the original recording – has become almost as widely identified with the genre as any other aspect of the music, and has been parodied in films such as Austin Powers in Goldmember, in which Mike Myers' character Dr. Evil – performing in a parody of a hip hop music video ("Hard Knock Life" by Jay-Z)– performs an entire verse that is blanked out. In 1995, Roger Ebert wrote:[92]

Rap has a bad reputation in white circles, where many people believe it consists of obscene and violent anti-white and anti-female guttural. Some of it does. Most does not. Most white listeners don't care; they hear black voices in a litany of discontent, and tune out. Yet rap plays the same role today as Bob Dylan did in 1960, giving voice to the hopes and angers of a generation, and a lot of rap is powerful writing.

In 1990, Luther Campbell and his group 2 Live Crew filed a lawsuit against Broward County Sheriff Nick Navarro, because Navarro wanted to prosecute stores that sold the group's album As Nasty As They Wanna Be because of its obscene and vulgar lyrics. In June 1990, U.S. district court judge labeled the album obscene and illegal to sell. However, in 1992, the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit overturned the obscenity ruling.

Until its discontinuation on July 8, 2006, BET ran a late-night segment titled BET: Uncut to air nearly-uncensored videos. The show was exemplified by music videos such as "Tip Drill" by Nelly which was criticized for what many viewed as an exploitative depiction of women, particularly images of a man swiping a credit card between a stripper's buttocks.

Product placement

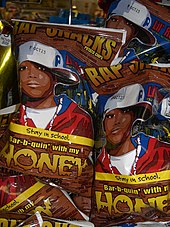

Critics such as Businessweek's David Kiley argue that the discussion of products within hip hop culture may actually be the result of undisclosed product placement deals.[93] Such critics allege that shilling or product placement takes place in commercial rap music, and that lyrical references to products are actually paid endorsements.[93] In 2005, a proposed plan by McDonalds to pay rappers to advertise McDonalds products in their music, was leaked to the press.[93] After Russell Simmons made a deal with Courvoisier to promote the brand among hip hop fans, Busta Rhymes recorded the song "Pass the Courvoisier".[93] Simmons insists that no money changed hands in the deal.[93]

The symbiotic relationship has also stretched to include car manufacturers, clothing designers and sneaker companies,[94] and many other companies have used the hip hop community to make their name or to give them credibility. One such beneficiary was Jacob the Jeweler, a diamond merchant from New York, Jacob Arabo's clientele included Sean Combs, Lil' Kim and Nas. He created jewellery pieces from precious metals that were heavily loaded with diamond and gemstones. As his name was mentioned in the song lyrics of his hip hop customers, his profile quickly rose. Arabo expanded his brand to include gem-encrusted watches that retail for hundreds of thousands of dollars, gaining so much attention that Cartier filed a trademark-infringement lawsuit against him for putting diamonds on the faces of their watches and reselling them without permission.[95] Arabo's profile increased steadily until his June 2006 arrest by the FBI on money laundering charges.[96]

While some brands welcome the support of the hip hop community, one brand that did not was Cristal champagne maker Louis Roederer. A 2006 article from The Economist magazine featured remarks from managing director Frederic Rouzaud about whether the brand's identification with rap stars could affect their company negatively. His answer was dismissive in tone: "That's a good question, but what can we do? We can't forbid people from buying it. I'm sure Dom Pérignon or Krug would be delighted to have their business." In retaliation, many hip hop icons such as Jay-Z and Sean Combs, who previously included references to "Cris", ceased all mentions and purchases of the champagne. 50 Cent's merge with Vitamin Water, Dr. Dre's promotion of his Beats by Dr. Dre headphone line and Dr. Pepper, and Drake's commercial with Sprite all act to effectively illustrate successful mergers.

Although not popular at the time, MC Hammer was an early predecessor of product placement. With merchandise such as dolls, commercials and numerous television show appearances, Hammer began the trend of rap artists being accepted as mainstream pitchmen.[97]

Media

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (December 2011) |

Hip Hop culture has had extensive coverage in the media, especially in relation to television; there have been a number of television shows devoted to or about hip hop. For many years, BET was the only television channel likely to play hip hop, but in recent years the mainstream channels VH1 and MTV have added a significant amount of hip hop to their play list. Run DMC became the first African-American group to appear on MTV.[98][99] With the emergence of the Internet a number of online sites began to offer hip hop related video content.

There have also been a number of hip hop films, movies which focused on hip hop as a subject. Some of these films include: Boyz n the Hood, Juice, Menace II Society, Notorious, and Get Rich Or Die Tryin'.

Hip Hop magazines have long detailed hip hop lifestyle and history, including the first known published hip hop publication The Hip Hop Hit List, which also contained the very first rap music record chart. Published in the early 1980s by two brothers from Newark, New Jersey, Vincent and Charles Carroll who was also a hip hop group known as The Nastee Boyz who knew the art form very well and noticed the void and the fact that DJs then did not recognize that there was a standard and shouldn't just be playing anything just because it was rap. The periodical began as the first Rap record chart and tip sheet for DJs and was distributed through national record pools and record stores throughout the New York City Tri-State area. One of the founding publishers Charles Carroll noted, "Back then, all DJs came into New York City to buy their records but most of them did not know what was hot enough to spend money on, so we charted it." Jae Burnett became Vincent Carroll's partner and played a very instrumental role in its later development.

Many New York tourist took the publication back home with them to other countries to share it creating worldwide interest in the culture and new art form. It had a printed distribution of 50,000 a circulation rate of 200,000 with well over 25,000 subscribers. The Hip Hop Hit List was also the first to define hip hop as a culture introducing the many aspects of the art form such as fashion, music, dance, the arts and most importantly the language. For instance on the cover the headliner included the tag "All Literature was Produced to Meet Street Comprehension!" which proved their loyalty not only to the culture but also to the streets. Most interviews were written verbatim which included their innovative broken English style of writing. Some of the early charts were written in the Graffiti format Tag style but was made legible enough for the masses.

The Carroll Brothers were also consultants to the many record companies who had no idea how to market the music. Vincent Carroll, the magazine's creator/publisher, went on to become a huge source for marketing and promoting the culture of Hip Hop, starting Blow-Up Media, the first Hip Hop Marketing Firm with offices in NYC's Tribeca district. At the age of 21 Vincent employed a staff of 15 and assisted in launching some of the cultures biggest and brightest stars.(the Fugees, Nelly, the Outzidaz,feat. Eminem and many more). Later other publications spawned up including: Hip Hop Connection, XXL, Scratch, The Source and Vibe.[100] Many individual cities have also produced their own local hip hop newsletters, while hip hop magazines with national distribution are found in a few other countries. The 21st century also ushered in the rise of online media, and hip hop fan sites now offer comprehensive hip hop coverage on a daily basis.

Diversification

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (March 2009) |

Hip hop music has spawned dozens of sub-genres which incorporate a domineering style of music production or rapping. The diversification process stems from the appropriation of hip hop culture by other ethinic groups.

There are many varying social influences that affect hip hop's message in different nations. It is frequently used as a musical response to perceived political and/or social injustices. In South Africa the largest form of hip hop is called Kwaito, which has had a growth similar to American hip hop. Kwaito is a direct reflection of a post apartheid South Africa and is a voice for the voiceless; a term that U.S. hip hop is often referred to. Kwaito is even perceived as a lifestyle, encompassing many aspects of life, including language and fashion.[101]

Kwaito is a political and party-driven genre, as performers use the music to express their political views, and also to express their desire to have a good time. Kwaito is a music that came from a once hated and oppressed people, but it is now sweeping the nation. The main consumers of Kwaito are adolescents and half of the South African population is under 21. Some of the large Kwaito artists have sold over 100,000 albums, and in an industry where 25,000 albums sold is considered a gold record, those are impressive numbers.[102] Kwaito allows the participation and creative engagement of otherwise socially excluded peoples in the generation of popular media.[103] South African hip hop is more diverse lately and there are hip hop acts in South Africa that have made an impact and continue making impact worldwide. These include Tumi, Ben Sharpa, HipHop Pantsula, Tuks Senganga.[104]

In Jamaica, the sounds of hip hop are derived from American and Jamaican influences. Jamaican hip hop is defined both through dancehall and reggae music. Jamaican Kool Herc brought the sound systems, technology, and techniques of reggae music to New York during the 1970s. Jamaican hip hop artists often rap in both Brooklyn and Jamaican accents. Jamaican hip hop subject matter is often influenced by outside and internal forces. Outside forces such as the bling-bling era of today's modern hip hop and internal influences coming from the use of anti-colonialism and marijuana or "ganja" references which Rastafarians believe bring them closer to God.[105][106][107]

Author Wayne Marshall argues that "Hip hop, as with any number of African-American cultural forms before it, offers a range of compelling and contradictory significations to Jamaican artist and audiences. From "modern blackness" to "foreign mind", transnational cosmopolitanism to militant pan-Africanism, radical remixology to outright mimicry, hip hop in Jamaica embodies the myriad ways that Jamaicans embrace, reject, and incorporate foreign yet familiar forms."[108]

In the developing world hip hop has made a considerable impact in the social context. Despite the lack of resources, hip hop has made considerable inroads.[47] Due to limited funds, hip hop artists are forced to use very basic tools, and even graffiti, an important aspect of the hip hop culture, is constrained due to its unavailability to the average person. Many hip hop artists that make it out of the developing world come to places like the United States in hopes of improving their situations. Maya Arulpragasm (AKA M.I.A.) is a Sri Lankan born hip hop artist in this situation. She claims, "I'm just trying to build some sort of bridge, I'm trying to create a third place, somewhere in between the developed world and the developing world.".[109] Another music artist using Hip hop to provide a positive message to young Africans is Emmanuel Jal who is a former child soldier from South Sudan. Jal is one of the few South Sudanese music artists to have broken through on an international level[110] with his unique form of Hip hop and a positive message in his lyrics.[111] Jal, has attracted the attention of mainstream media and academics with his story and use of Hip hop as a healing medium for war afflicted people in Africa and has also been sought out for the international lecture circuit with major talks at popular talkfests like TED.[112]

Education

Many organizations and facilities are providing spaces and programs for communities to explore making and learning about hip hop. A noteworthy example is the IMP Labs in Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. Many dance studios and colleges now offer lessons in Hip Hop alongside Tap and Ballet. As well as KRS-ONE teaching hip hop lectures at Harvard University.

Hip hop producer 9th Wonder and former rapper/actor Christopher "Play" Martin from the hip hop group Kid-n-Play have both taught hip hop history classes at North Carolina Central University[113] and 9th Wonder has also taught a "Hip Hop Sampling Soul" class at Duke University.[114] In 2007, the Cornell University Library established the Hip Hop Collection to collect and make accessible the historical artifacts of Hip Hop culture and to ensure their preservation for future generations.[115]

Legacy

Having its roots in reggae, disco and funk, hip hop has since exponentially expanded into a widely accepted form of representation world wide. It expansion includes events like Afrika Bambaataa releasing "Planet Rock" in 1982, which tried to establish a more global harmony in hip hop. In the 1980s, the British Slick Rick became the first international hit hip hop artist not native to America. From the 1980s onward, television became the major source of widespread outsourcing of hip hop to the global world. From Yo! MTV Raps to Public Enemy's world tour, hip hop spread further to Latin America and became a mainstream culture within the given context. As follows, hip hop has been cut mixed and changed to the areas that adapt to it.[116][unreliable source?]

Early hip hop has often been credited with helping to reduce inner-city gang violence by replacing physical violence with hip hop battles of dance and artwork. However, with the emergence of commercial and crime-related rap during the early 1990s, an emphasis on violence was incorporated, with many rappers boasting about drugs, weapons, misogyny, and violence. While hip hop music now appeals to a broader demographic, media critics argue that socially and politically conscious hip hop has long been disregarded by mainstream America in favor of its media-baiting sibling, gangsta rap.[117]

Many artists are now considered to be alternative hip hop when they attempt to reflect what they believe to be the original elements of the culture. Artists/groups such as Lupe Fiasco, Immortal Technique, Lowkey, Brother Ali, The Roots, Shing02, Jay Electronica, Nas, Common, Talib Kweli, Mos Def, Dilated Peoples, Dead Prez, Blackalicious, Jurassic 5, Jeru the Damaja, Kendrick Lamar, Gangstarr, KRS-One, Living Legends and hundreds more emphasize messages of verbal skill, internal/external conflicts, life lessons, unity, social issues, or activism.

Authenticity

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (October 2012) |

Authenticity is often a serious debate within hip hop culture. Dating back to its origins in the 1970s in the Bronx, hip hop revolved around a culture of protest and freedom of expression in the wake of oppression suffered by African-Americans. As hip hop has become less of an underground culture, it is subject to debate whether or not the spirit of hip hop is embodied in protest, or whether it can evolve to exist in a marketable integrated version.[118] In "Authenticity Within Hip Hop and Other Cultures Threatened with Assimilation", Commentator Kembrew McLeod argues that hip hop culture is actually threatened with assimilation by a larger, mainstream culture.[119]

Believing that hip hop should be utilized as a voice for social justice, Tate points out that in the marketable version of hip hop, there isn't a role for this evolved genre in context of the original theme hip hop originated from (freedom from oppression). The problem with Black progressive political organizing isn't hip hop, but that the No. 1 issue on the table needs to be poverty, and nobody knows how to make poverty sexy.[120]

Tate discusses how the dynamic of progressive Black politics cannot apply to the genre of hip hop in the current state today due to the genre's heavy involvement in the market. In his article he discusses hip hop's 30th birthday and how its evolution has become more of a devolution due to its capitalistic endeavors. Both Tate and McLeod argue that hip hop has lost its authenticity due to its losing sight of the revolutionary theme and humble "folksy" beginnings the music originated from.

"This is the first time artists from around the world will be performing in an international context. The ones that are coming are considered to be the key members of the contemporary underground hip hop movement." This is how the music landscape has broadened around the world over the last ten years. The maturation of hip hop has gotten older with the genres age, but the initial reasoning of why hip hop has started will always be intact.

The pejorative term "poseur" is applied to those who associate with hip hop and adopt its stylistic attributes but are deemed not to share or understand the underlying values or philosophy.

Criticisms

Given its extensive roots in underground music, many hip hop and rap pioneers decry the modern messages portrayed in hip hop.[121] In particular, seminal figures in the early shift to the mainstream label modern hip hop artists as more concerned with image over substance.[122] This has led many critics to ridicule hip hop for the cultural stereotyping and faux gangster stylings portrayed by its current leading artists.

See also

- List of hip hop genres

- List of hip hop albums

- List of hip hop musicians

- List of films with associated hip hop songs

References

- Notes

- ^ a b Chang, Jeff (2005). Can't Stop Won't Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-30143-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Castillo-Garstow, Melissa (1). "Latinos in Hip Hop to Reggaeton". Latin Beat Magazine. 15 (2): 24(4).

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Rojas, Sal (2007). "Estados Unidos Latin Lingo". Zona de Obras (47). Zaragoza, Spain: 68.

- ^ Allatson, Paul. Key Terms in Latino/a Cultural and Literary Studies. Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons, 2007, 199.

- ^ Schloss, Joseph G. Foundation: B-boys, B-girls and Hip-Hop Culture in New York. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009, 125.

- ^ From Mambo to Hip Hop. Dir. Henry Chalfant. Thirteen / WNET, 2006, film

- ^ Kugelberg, Johan (2007). Born in the Bronx. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7893-1540-3.

- ^ Brown, Lauren (February 18, 2009). "Hip to the Game – Dance World vs. Music Industry, The Battle for Hip Hop's Legacy". Movmnt Magazine. Retrieved July 30, 2009.

- ^ Chang, Jeff (2005). Can't Stop Won't Stop: A History of the Hip Hop Generation. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 90. ISBN 0-312-30143-X.

- ^ Walker, Jason (January 31, 2005). "Crazy Legs – The Revolutionary". SixShot.com. Web Media Entertainment Gmbh. Retrieved August 27, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ THE HISTORY OF HIP HOP Retrieved on August 27, 2011

- ^ Rosen, Jody (February 12, 2006). "A Rolling Shout-Out to Hip-Hop History". The New York Times. p. 32. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

- ^ JET (April 02, 2007) "Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame". Johnson Publishing Company, pp.36–37

- ^ a b "Keith Cowboy – The Real Mc Coy". Web.archive.org. March 17, 2006. Archived from the original on March 17, 2006. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ^ "Zulu Nation: History of Hip-Hop". webcache.googleusercontent.com. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ http://www.zulunation.com/hip_hop_history2.htm (cached)

- ^ Hermes, Will (October 29, 2006). "All Rise for the National Anthem of Hip-Hop". New York Times. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ^ Campbell & Chang 2005, p. ??.

- ^ Article about MelleMel (Melle Mel) at AllHipHop.com[dead link]

- ^ Browne, P “The guide to United States popular culture” Popular Press, 2001. p. 386

- ^ Kool Herc, in Israel (director), The Freshest Kids: A History of the B-Boy, QD3, 2002.

- ^ History of Hip Hop—Written by Davey D

- ^ a b "The Story of Rapper's Delight by Nile Rodgers". RapProject.tv. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- ^ Lee, Jennifer 8. (January 15, 2008). "Tenants Might Buy Birthplace of Hip-Hop" (weblog). The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Kenner, Rob. "Dancehall," In The Vibe History of Hip-hop, ed. Alan Light, 350-7. New York: Three Rivers Press, 1999.

- ^ Toop, David. The Rap Attack: African Jive to New York Hip Hop. Boston: South End P. 1984 Print.

- ^ Forman M; Neal M “That’s the joint! The hip-hop studies reader”, Routledge, 2004. p. 2

- ^ SamplesDB – Afrika Bambaataa's Track

- ^ Reese, Renford. "From the fringe: The Hip hop culture and ethnic relations". popular culture review. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Grandmaster Flash. "Grandmaster Flash: Interview". Prefixmag.com. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ Rose 1994, pp. 53–55.

- ^ "Hip Hop Pioneer Doug E. Fresh & Soca Sensation Machel Montano To Host 26th Int'l Reggae & World Music Awards (IRAWMA)". Jamaicans.com. April 9, 2007. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ Rose 1994, p. 192.

- ^ a b c Chang 2007, p. 62.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Pareles, Jon (March 13, 2007). "The Message From Last Night: Hip-Hop is Rock 'n' Roll, and the Hall of Fame Likes It". The New York Times. p. 3. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Diawara 1998, pp. 237–76

- ^ a b Strode, Tim, and Tim Wood. "The Hip Hop Reader". New York: Pearson Education Inc., 2008. Print

- ^ Hess, Mickey, ed. "Hip Hop In America: A Regional Guide". Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Press, 2010. Print

- ^ Kitwana, Bakari. "Why White Kids Love Hip Hop: Wankstas, Wiggers, Wannabes, and the New Reality of Race in America". New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2005. Print

- ^ Media coverage of the Hip-Hop Culture – By Brendan Butler, Ethics In Journalism, Miami University Department of English[dead link]

- ^ "Hip-Hop Culture Crosses Social Barriers"[dead link]

- ^ "Hip Hop: National Geographic World Music". Worldmusic.nationalgeographic.com. October 17, 2002. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ "CNN.com – WorldBeat – Hip-hop music goes global – January 15, 2001". CNN. January 15, 2001. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ Comments (0) By Robert Christgau Tuesday, May 7, 2002 (May 7, 2002). "Planet Rock by Robert Christgau". village voice. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Christgau, Robert. "The World's Most Local Pop Music Goes International", The Village Voice, May 7, 2002. Retrieved on Apr 16, 2008.

- ^ a b Schwartz, Mark. "Planet Rock: Hip Hop Supa National" in Light 1999, pp. 361–72.

- ^ "Five Steez releases 'War for Peace' Album". The Jamaica Star. August 23, 2012. Retrieved December 28, 2012.

- ^ a b Hartwig Vens. “Hip-hop speaks to the reality of Israel”. WorldPress. November 20, 2003. March 24, 2008.

- ^ Chang 2007, p. 65.

- ^ a b c Chang 2007, p. 60.

- ^ Michael Wanguhu. Hip-Hop Colony (documentary film).

- ^ Wayne Marshall, "Nu Whirl Music, Blogged in Translation?"

- ^ Lane, Nadia (March 30, 2011). "Libyan Rap Fuels Rebellion". CNN iReport. Cable News Network. Retrieved August 16, 2011.

- ^ "The Commodification of Hip Hop, Brooke Daniel and Kellon Innocent". Ilovepwnage.com.

- ^ "Rap Criticism Grows Within Own Community, Debate Rages Over It's (sic) Effect On Society As It Struggles With Alarming Sales Decline – The ShowBuzz". Showbuzz.cbsnews.com. February 17, 2010. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ a b Tate, Greg. “Hip-hop Turns 30: Whatcha Celebratin’ For?” Village Voice. January 4, 2005.

- ^ New York Times

- ^ "Music and Human Evolution". Mca.org.au. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. xii.

- ^ Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 3.

- ^ Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 81.

- ^ "Rapping – definition". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. 2009.

- ^ Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. x.

- ^ "The Origin | Hip Hop Cultural Center". Originhiphop.com. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ^ Attridge, Derek, 2002, Poetic Rhythm: An Introduction, Cambridge University Press, p. 90

- ^ Edwards, Paul, 2009, How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, Chicago Review Press, p. 63.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ "Hip-Hop, The history". Independence.co.uk. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- ^ a b c Shapiro 2007.

- ^ "A History of Graffiti in Its Own Words". New York Magazine. unknown.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ David Toop, Rap Attack, 3rd ed., London: Serpent's Tail, 2000.

- ^ "history of Graffiti". Scribd.com. December 19, 2009. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ^ Adaso, Henry. "Hip-Hop Timeline:1925 to Present". About.com. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- ^ “Earl ‘Snakehips’ Tucker”. Drop Me off in Harlem. Kennedy Center. 2003. Web. Jan 31, 2010.

- ^ "Drop Me Off in Harlem". Artsedge.kennedy-center.org. Retrieved April 23, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ O'Connor, Ryan (December 2010). "Breaking Down Limits Through Hip Hop". nthWORD Magazine (8). nthWORD LLC: 3–6.

- ^ Hess, M. (2007). Icons of hip hop: an encyclopedia of the movement, music, and culture, Volume 1, Greenwood Publishing Group

- ^ Perry, I. (2004). Prophets of the hood: politics and poetics in hip hop, Duke University Press

- ^ Asante, Molefi K. It's Bigger Than Hip Hop : the Rise of the Post-hip-hop Generation. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2008. pp. 21–23

- ^ a b Patterson, Orlando. "Global Culture and the American Cosmos". The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Paper Number 21994 01Feb2008.

- ^ "Hip-Hop: The "Rapper's Delight"". America.gov. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ Alridge D, Steward J. “Introduction: Hip Hop in History: Past, Present, and Future”, Journal of African American History 2005. p. 190

- ^ "s hip hop driving the Arab Spring?". BBC News. July 24, 2011.

- ^ a b Motion live entertainment. Stylo, Saada. "The Northside research Project: Profiling Hip Hop artistry in Canada". p. 10, 2006.

- ^ "Dr. Renford R. Reese's Homepage". Csupomona.edu. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ Alim, Samy. "Roc the Mic Right: The Language of Hip Hop Culture. Taylor & Francis, 2006. September 27, 2010".

- ^ Asante, Molefi K. It's Bigger Than Hip Hop : the Rise of the Post-hip-hop Generation. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2008. pp. 106–108

- ^ Thomas, G. "Hip-Hop Revolution In The Flesh. xi. Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. September 27, 2010".

- ^ Morrell, Ernest. Andrade, Jeffery Duncan. "Promoting Academic Literacy with Urban Youth Through Engaging Hip Hop Culture". p. 10, 2003.

- ^ Evan Serpick (July 9, 2006). "MTV: Play It Again". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ Roger Ebert (August 11, 1995). "Reviews: Dangerous Minds". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ a b c d e Kiley, David. Hip Hop Two-Step Over Product Placement BusinessWeek Online, April 6, 2005. Retrieved January 5, 2007.

- ^ Ben Johnson. "Cover Story: Frock Band". SILive.com. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ^ Williams, Corey (November 1, 2006). "'Jacob the Jeweler' pleads guilty". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- ^ Sales, Nancy Jo (October 31, 2007). "Is Hip-Hop's Jeweler on the Rocks?". Vanity Fair (magazine). Retrieved April 14, 2008.

- ^ Bois, Jon (June 25, 2010). "MC Hammer To Perform At Reds Game, Will Hopefully Refrain From Hurting Them". SBNation.com. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ “Hip-hop” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2010. Web. Jan 31, 2010.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. "hip-hop (cultural movement) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ Kitwana 2005, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Robinson, Simon (April 11, 2004). "TIMEeurope Magazine | Viewpoint". Time. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ "Kwaito: much more than music –". Southafrica.info. January 7, 2003. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ Steingo 2005.

- ^ "african hip hop". south african hip hop. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Bling-bling for Rastafari: How Jamaicans deal with hip hop by Wayne Marshall

- ^ https://moodle.brandeis.edu/file.php/3404/pdfs/marshall-bling-bling.pdf/

- ^ "Reggae Music 101 – Learn More About Reggae Music – History of Reggae". Worldmusic.about.com. November 4, 2009. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

- ^ Marshall, Wayne Bling-Bling ForRastafari: How Jamaicans Deal With Hip-HopSocial and Economic Studies 55:1&2 (2006):49–74

- ^ Sisario, Ben (August 19, 2007). "An Itinerant Refugee in a Hip-Hop World". The New York Times. p. 20. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^ Story on Emmanuel Jal in National Geographic.

- ^ Jane Stevenson, "Emmanuel Jal uses music as therapy", Toronto Sun, August 8, 2012.

- ^ TALK: Emmanuel Jal: The music of a war child on Video Link on TED, July 2009.

- ^ North Carolina Central University. Christopher Martin biography. Accessed September 30, 2010.

- ^ Duke University. Patrick Douthit aka 9th Wonder, Cover to Cover. Accessed September 30, 2010.

- ^ Kenney, Anne R. "Cornell University Library Annual Report, 2007-2008" (PDF). Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ^ Watkins, S. Craig. "Why Hip-Hop Is Like No Other" in Chang 2007, p. 63.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ See for instance Rose 1994, pp. 39–40.

- ^ McLeod 1999.

- ^ Tate, Greg. "Hip-hop Turns 30: Whatcha Celebratin’ For?" Village Voice, January 4, 2005.

- ^ http://www.spinner.com/2012/09/07/public-enemy-chuck-d-young-rappers/

- ^ http://www.starpulse.com/news/index.php/2011/09/19/icet_slams_modern_hiphop_music

- Bibliography

- Ahearn, Charlie; Fricke, Jim, eds. (2002). Yes Yes Y'All: The Experience Music Project Oral History of Hip Hop's First Decade. New York City, New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81184-7.

- Campbell, Clive; Chang, Jeff (2005). Can't Stop Won't Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation. New York City, New York: Picador. ISBN 0-312-42579-1.

- Chang, Jeff (November–December 2007). "It's a Hip-hop World". Foreign Policy (163): 58–65.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Corvino, Daniel; Livernoche, Shawn (2000). A Brief History of Rhyme and Bass: Growing Up With Hip Hop. Tinicum, Pennsylvania: Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 1-4010-2851-9.

- Diawara, Manthia (1998). In Search of Africa. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-44611-9.

- Gordon, Lewis R. (October/December 2005). "The Problem of Maturity in Hip Hop". Review of Education, Pedagogy and Cultural Studies. 27 (4): 367–389. doi:10.1080/10714410500339020.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hager, Steven (1984). Hip Hop: The Illustrated History of Breaking Dancing, Rap Music and Graffiti. New York City, New York: St. Martins' Press. ISBN 0312373171.

- Kelly, Robin D. G. (1994). Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class. New York City, New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-684-82639-9.

- Kitwana, Bakari (2002). The Hip-Hop Generation: Young Blacks and the Crisis in African American Culture. New York City, New York: Perseus Books Group. ISBN 0-465-02979-5.

- Kitwana, Bakari (2005). Why White Kids Love Hip Hop: Wankstas, Wiggers, Wannabes and the New Reality of Race in America. New York City, New York: Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 0-465-03746-1.

- Kolbowski, Silvia (Winter 1998). "Homeboy Cosmopolitan". October (83): 51.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Light, Alan, ed. (1999). The VIBE History of Hip-Hop (1st ed.). New York City, New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-609-80503-7.

- McLeod, Kembrew (Autumn 1999). "Authenticity Within Hip-Hop and Other Cultures Threatened with Assimilation" (PDF 1448.9 KB). Journal of Communication. 49 (4): 134–150. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1999.tb02821.x.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nelson, George (2005). Hip-Hop America (2nd ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-028022-7.

- Ogbar, Jeffrey O. G. (2007). Hip-Hop Revolution: The Culture and Politics of Rap. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1547-6.

- Perkins, William E. (1995). Droppin' Science: Critical Essays on Rap Music and Hip Hop Culture. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University Press. ISBN 1-56639-362-0.

- Ro, Ronin (2001). Bad Boy: The Influence of Sean "Puffy" Combs on the Music Industry. New York City, New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0-7434-2823-4.

- Rose, Tricia (1994). Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0-8195-6275-0.

- Shapiro, Peter (2007). Rough Guide to Hip Hop (2nd ed.). London, UK: Rough Guides. ISBN 1-84353-263-8.

- Steingo, Gavin (July 2005). "South African Music after Apartheid: Kwaito, the "Party Politic," and the Appropriation of Gold as a Sign of Success". Popular Music and Society. 28 (3): 333–357. doi:10.1080/03007760500105172.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Toop, David (1991). Rap Attack 2: African Rap to Global Hip Hop (2nd ed.). New York City, New York: Serpent's Tail. ISBN 1-85242-243-2.