History of Libya

| History of Libya | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The History of Libya includes the history of its rich mix of people added to the indigenous Berber tribes. For most of their history, the people of Libya have been subjected to varying degrees of foreign control. The modern history of independent Libya began in 1951.

The history of Libya comprises six distinct periods: Ancient Libya, the Roman era, the Islamic era, Ottoman rule, Italian rule, and the Modern era.

Pre-Roman Libya

- See also Ancient Libya (Tripolitania and Cyrenaica)

Archaeological evidence[citation needed] indicates that from at least the eighth millennium BC. Libya's coastal plain shared in a Neolithic culture, skilled in the domestication of cattle and cultivation of crops, that was common to the whole Mediterranean littoral. To the south, in what is now the Sahara Desert, nomadic hunters and herders roamed a far, well-watered savanna that abounded in game and provided pastures for their stock. Their culture flourished until the region began to desiccate after 2000 BC. Scattering before the encroaching desert and invading horsemen, the savanna people migrated into the Sudan or were absorbed by the Berbers.[1]

The origin of the Berbers is a partial mystery, the investigation of which has produced an abundance of educated speculation but no solution. Archaeological and linguistic evidence strongly suggests southwestern Asia as the point from which the ancestors of the Berbers may have begun their migration into North Africa early in the third millennium BC. Over the succeeding centuries they extended their range from Egypt to the Niger Basin. Caucasians of predominantly Mediterranean stock, the Berbers present a broad range of physical types and speak a variety of mutually unintelligible dialects that belong to the Afro-Asiatic language family. They never developed a sense of nationhood and have historically identified themselves in terms of their tribe, clan, and family. Collectively, Berbers refer to themselves simply as imazighan, to which has been attributed the meaning "free men."[1]

Inscriptions found in Egypt dating from the Old Kingdom (ca. 2700–2200 BC) are the earliest known recorded testimony of the Berber migration and also the earliest written documentation of Libyan history. At least as early as this period, troublesome Berber tribes, one of which was identified in Egyptian records as the Levu (or "Libyans"), were raiding eastward as far as the Nile Delta and attempting to settle there. During the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2200-1700 BC) the Egyptian pharaohs succeeded in imposing their overlordship on these eastern Berbers and extracted tribute from them. Many Berbers served in the army of the pharaohs, and some rose to positions of importance in the Egyptian state. One such Berber officer seized control of Egypt in about 950 BC and, as Shishonk I, ruled as pharaoh. His successors of the twentysecond and twenty-third dynasties—the so-called Libyan dynasties (ca. 945–730 BC)—are also believed to have been Berbers.[1]

To the Ancient Greeks, Libya was one of the three known continents along with Asia and Europe. In this sense, Libya was the whole known African continent to the west of the Nile Valley and extended south of Egypt. Herodotus described the inhabitants of Libya as two peoples: The Libyans in northern Africa and the Ethiopians in the south. According to Herodotus, Libya began where ancient Egypt ended, and extended to Cape Spartel, south of Tangier on the Atlantic coast. Both the Greeks and the Phoenicians colonized North African soil, and Punic civilization emerged, although its central city of Carthage was not in present-day Libya but in neighboring Tunisia.

The territory of modern Libya had separate histories until Roman times, as Tripoli and Cyrenaica.

Cyrenaica was Greek before it was Roman. It was also known as Pentapolis, the "five cities" being Cyrene (near the village of Shahat) with its port of Apollonia (Marsa Susa), Arsinoe (Tocra), Berenice (Bengazi) and Barca (Merj). From the oldest and most famous of the Greek colonies the fertile coastal plain took the name of Cyrenaica.

Roman Libya

The Romans conquered Tripolitania (the region around Tripoli) in 106 BC. Ptolemy Apion, the last Greek ruler, bequeathed Cyrenaica to Rome, which formally annexed the region in 74 BC and joined it to Crete as a Roman province. By 64 BC, Julius Caesar's legions had established their occupation, and the Romans had thus unified all three regions of Libya (Tripolitania, Cirenaica and northern Fezzan) in one single new province called Africa proconsularis (later Cirenaica was separated administratively).

As a Roman province, Libya was prosperous, and reached a golden age in the 2nd century AD, when the city of Leptis Magna rivalled Carthage and Alexandria in prominence. For more than 400 years, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were wealthy Roman provinces and part of a cosmopolitan state whose citizens shared a common language, legal system, and Roman identity. Roman ruins like those of Leptis Magna, extant in present-day Libya, attest to the vitality of the region, where populous cities and even smaller towns enjoyed the amenities of urban life - the forum, markets, public entertainments, and baths - found in every corner of the Roman Empire. Merchants and artisans from many parts of the Roman world established themselves in coastal Libya and the province was greatly "Romanized", according to Theodore Mommsen. But the character of the cities of Tripolitania remained partially Punic and, in Cyrenaica, Greek. The predominant religion was Christianity, but there was even a huge Jewish community (mainly in Cyrenaica).

Tripolitania was a major exporter of olive oil (produced there with the Centenaria farm system, protected by the Limes Tripolitanus), as well as a centre for the gold and slaves conveyed to the coast by the Garamentes, while Cyrenaica remained an important source of wines, drugs, and horses.

As part of his reorganization of the empire in 300 AD, the Emperor Diocletian separated the administration of Crete from Cyrenaica and in the latter formed the new provinces of "Upper Libya" and "Lower Libya", using the term Libya for the first time as an administrative designation. With the definitive partition of the empire in 395 AD, the Libyans of Cirenaica were assigned to the eastern empire; Tripolitania was attached to the Western Roman empire.

The Islamic Period

Early Islamic rule

- See also Islamic Tripolitania and Cyrenaica

In 647 an army of 40,000 Arabs, led by ‘Abdu’llah ibn Sa‘ad, the foster-brother of Caliph Uthman ibn Affan, had come to overtake Libya from the Byzantines. Tripoli was taken from the Byzantines, followed by Sufetula, a city 150 miles south of Carthage, where the Exarch Gregory was killed. Following the revolt, Gennadius fled to Damascus and asked for aid from Muawiyah, to whom he had paid tribute for years. The caliph sent a sizable force with Gennadius to spread Islam in Africa in 665. Even though the deposed exarch died after reaching Alexandria, the Arabs marched on. The Byzantines dispatched an army to reinforce Africa, but its commander Nicephorus the Patrician lost a battle with the Arabs and reembarked. Uqba ibn Nafi and Abu Muhajir al Dinar did much to promote Islam and in the following centuries most of the indigenous peoples converted.

In 750 the Abbasid dynasty overthrew the Ummayad caliph and shifted the capital to Baghdad, with emirs retaining nominal control over the Libyan coast on behalf of the far-distant caliph. In 800 Caliph Harun ar-Rashid appointed Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab as his governor. The Aghlabids dynasty effectively became independent of the Baghdad caliphs, who continued to retain spiritual authority. The Aghlabid emirs took their custodianship of Libya seriously, repairing Roman irrigation systems, restoring order and bringing a measure of prosperity to the region.

However, this prosperity was followed by economic and political collapse[2] and then the Hilalian invasion of 1050-1052. Groups of bedouin,[3] pastorialists from Upper Egypt, left the degraded grasslands on the upper Nile and headed westward into Libya, destroying the fields and gardens of the inhabitants.[4] Ibn Khaldun compared the invasion to a swarm of locusts.[5] The leading tribe of these bedouin were the Banu Hilal, hence the name Hilalian invasion.[3]

Libya under the Ottomans (1551-1911)

- See also Ottoman Rule (15th–1912)

By the beginning of the 16th century the Libyan coast had minimal central authority and its harbours were havens for pirates. Habsburg Spain occupied Tripoli in 1510, but the Spaniards were more concerned with controlling the port than with the inconveniences of administering a colony. In 1538 Tripoli was reconquered by a pirate king called Khair ad-Din (known more evocatively as Barbarossa, or Red Beard) and the coast became renowned as the Barbary Coast.

When the Ottomans arrived to occupy Tripoli in 1551, they saw little reason to rein in the pirates, preferring instead to profit from the booty. It would be more than two centuries before the pirates' control of the region was challenged.

Under the Ottomans, the Meghreb was divided into three provinces, Algiers, Tripoli and Tunis. After 1565, administrative authority in a pasha appointed by the sultan in Constantinople. The sultan provided the pasha with a corps of janissaries, which was in turn divided into a number of companies under the command of a junior officer or bey. The janissaries quickly became the dominant force in Ottoman Libya.

In 1711, Ahmed Karamanli, an Ottoman cavalry officer, seized power and founded the Karamanli dynasty, which would last 124 years. The Libyan Civil War of 1791–1795 occured in those years.

In May 1801 Pasha Yusuf Karamanli demanded from the United States an increase in the tribute ($83,000) which that government had paid since 1796 for the protection of their commerce from piracy. The demand was refused, a United States of America naval force blockaded Tripoli, and a desultory war dragged on until 3 June 1805.

The Second Barbary War (1815, also known as the Algerine or Algerian War) was the second of two wars fought between the United States of America and the Ottoman Empire's North African regencies of Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis, known collectively as the Barbary States.

In 1814, the government of Sultan Mahmud II took advantage of local disturbances to reassert their direct authority and held it until the final collapse of the Ottoman Empire. As decentralized Ottoman power had resulted in the virtual independence of Egypt as well as Tripoli, the coast and desert lying between them relapsed to anarchy, even after direct Ottoman control was resumed in Tripoli. Over a 75 year period the Ottoman Turks provided 33 governors and Libya remained part of the empire — although at times virtually autonomous — until Italy invaded it in 1911 in the Italo-Turkish War, as the Ottoman Empire was collapsing.

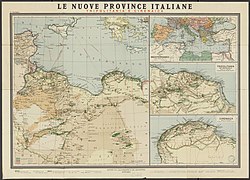

Italian rule (1911-1943)

- See also Italo-Turkish War and Italian Colony (1911–1947)

The Italian rule in Libya started with the Italian conquest of coastal Tripolitania and Cyrenaica from the Ottomans in 1911. It lasted more than thirty years until February 1943, when western Tripolitania was conquered by the Allies in the North African Campaign. Officially Italy renounced to Libya in 1947, in the Peace Treaty after World War II. Probably the most important legacy of the Italian rule -according to historians like Chapin Metz- is the political creation of "Libya" with the unification of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan in 1934.

The Italo-Turkish War and Italian Libya

The attempted Italian colonization of the Ottoman provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica was never wholly successful, at least initially. On 3 October 1911 the Italians attacked Tripoli, claiming somewhat disingenuously to be liberating Libya from Ottoman rule. Despite a major revolt by the Libyans, the Ottoman sultan ceded Libya to the Italians by signing the 1912 Treaty of Lausanne.

After the withdraw of the Ottoman army the Italian could easily extend their occupation of the country, seizing East Tripolitania,[6] Gadames, the Djebel and Fezzan with Murzuk during 1913.[7] The outbreak of the First World War with the necessity to bring back the troops to Italy, the proclamation of the Holy War by the Ottomans, the uprising of the Libyans in Tripolitania and Fezzan and the partisan war led by the Senussi in Cyrenaica [8] forced the Italians to abandon all the occupied territory and to entrench themselves in Tripoli, Derna and the coast of Cyrenaica.[7] Only in the late 1920s were the Italians able to take control of all Libya. Meanwhile 150,000 Italians settled in Libya between 1920 and 1940, greatly developing Italian Libya in all areas.

At the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, the Kingdom of Italy did not receive any part of the German colonies. Instead, France agreed to give some Saharan territories to the Italian Libya, and the Oltre Giuba in Somalia was given to Italy by Great Britain. After many discussions during the 1920s, in 1935 the Mussolini-Laval agreement was made and Italy received the Aouzou strip, which was united to the newly created Italian colony of Libya.

On 25 October 1920 the Italian government recognized Sheikh Sidi Idris the hereditary head of the nomadic Senussi, with wide authority in Kufra and other oases, as Emir of Cyrenaica, a new title extended by the British at the close of World War I. The emir would eventually become king of the free Libyan state.

Libya under fascism

Fighting intensified after the accession to power in Italy of the dictator Benito Mussolini. Idris (later King of Libya) fled to Egypt in 1922. From 1922 to 1928, Italian forces under General Badoglio waged a punitive pacification campaign. Badoglio's successor in the field, Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, accepted the commission from Mussolini on the condition that he was allowed to crush Libyan resistance unencumbered by the restraints of either Italian or international law. Mussolini reportedly agreed immediately and Graziani intensified the oppression. Some Libyans continued to defend themselves, with the strongest voices of dissent coming from the Cyrenaica. Omar Mukhtar, a Senussi sheikh, became the leader of the uprising.

After a much-disputed truce on 3 January 1928, the Italian policy in Libya reached the level of full scale war, including deportation and concentration of the people of the Jebel Akhdar to deny the rebels the support of the local population. After Al-Mukhtar's capture September 15, 1931 and his execution in Benghazi, the resistance petered out. Limited resistance to the Italian occupation crystallized round the person of Sheik Idris, the Emir of Cyrenaica.

By 1934, Libya was fully pacified and the new Italian governor Italo Balbo started a policy of integration between the Arabs and the Italians. Indeed in 1939, laws were passed that allowed Muslims to be permitted to join the National Fascist Party and in particular the Muslim Association of the Lictor (Associazione Musulmana del Littorio), and the 1939 reforms allowed the creation of Libyan military units within the Italian army.[9] As a consequence during WWII there was a strong support for Italy between many Muslim Libyans, who enrolled in the Italian Army [10]

The governor Balbo (after the creation of "Libya" in 1934, with the unification of Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan in a single country) developed the Italian Libya from 1934 to 1940, creating a huge infrastructure (from 4,000 km of roads to 400 km of narrow gauge railways to new industries and to dozen of new agricultural villages).[11]

The Libyan economy nearly "boomed", mainly in the agricultural sector. Even some manufacturing activities were developed, mostly related to the food industry. Building construction increased in a huge way. Furthermore, the Italians made modern medical care available for the first time in Libya and improved sanitary conditions in the towns.

Howard Christie wrote that The Italians started numerous and diverse businesses in Tripolitania and Cirenaica. These included an explosives factory, railway workshops, Fiat Motor works, various food processing plants, electrical engineering workshops, ironworks, water plants, agricultural machinery factories, breweries, distilleries, biscuit factories, a tobacco factory, tanneries, bakeries, lime, brick and cement works, Esparto grass industry, mechanical saw mills, and the Petrolibya Society (Trye 1998). Italian investment in her colony was to take advantage of new colonists and to make it more self-sufficient. Total native Italian population for Libya was 110,575 out of a total population of 915,440 in 1940 (General Staff War Office 1939, 165/b).[12]

Governor Balbo promoted the construction of many new villages [13] for many thousands of Italian colonists in the coastal areas of Italian Libya. He promoted even the creation of new villages for the Arabs.

In 13 September 1940, Mussolini's highway was used for the invasion of Egypt by Italian forces stationed in Libya. Counterattacks of British Allied forces from Egypt, commanded by Wavell and their successful two-month campaign in (Tobruk, Bengasi, El Agheila), and the counteroffensives under Rommel in 1940-43, all took place during World War II. In November 1942, the Allied forces retook Cyrenaica; by February 1943, the last German and Italian soldiers were driven from Libya.

Post-World War II and preparation for independence

In the early post-war period, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica remained under British administration, while the French controlled Fezzan. In 1944, Idris returned from exile in Cairo but declined to resume permanent residence in Cyrenaica until the removal in 1947 of some aspects of foreign control. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy, which hoped to maintain the colony of Tripolitania, (and France, which wanted the Fezzan), relinquished all claims to Libya. Libya so remained united.

Severe anti-Jewish violence erupted in Libya following the liberation of North Africa by Allied troops. From November 5 to November 7, 1945, more than 140 Jews (including 36 children) were killed and hundreds injured in a pogrom in Tripoli. Five synagogues in Tripoli and four in provincial towns were destroyed, and over 1,000 Jewish residences and commercial buildings were plundered in Tripoli alone.[14][15][16] In June 1948, anti-Jewish rioters in Libya killed another 12 Jews and destroyed 280 Jewish homes.[15] The fear and insecurity which arose from these anti-Jewish attacks and the founding of the state of Israel led many Jews to flee Libya. From 1948 to 1951, 30,972 Libyan Jews moved to Israel.[17] By 1970s, the rest of Libyan Jews (some 7,000) were evacuated to Italy.

On 21 November 1949 the UN General Assembly passed a resolution stating that Libya should become independent before 1 January 1952. Idris represented Libya in the subsequent UN negotiations.

Independent Libya

Prior to World War II Libya had been a colony of Italy until Italian forces were driven out by the Allies in 1943. Libya came under the control of France and the United Kingdom as a UN Trusteeship in 1947 when Italy formally relinquished its claim to Libya. As part of the arrangement the United Kingdom and France governed the three historical regions of Libya Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Fezzan.

The UK was responsible for Tripolitania and Cyrenaica and France was responsible for Fezzan. On 21 November 1949, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution that Libya should become independent before 1 January 1952.

Kingdom of Libya (1951-1969)

Idris as-Senussi, the Emir of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica and the leader of the Senussi Muslim Sufi order, represented Libya in the UN negotiations, and on 24 December 1951, Libya declared its independence with representatives from Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan declaring a union with the country being called the United Kingdom of Libya, and Idris as-Senussi being offered the crown. In accordance with the constitution the new country had a federal government with the three states of Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan having autonomy. The kingdom also had three capital cities: Tripoli, Benghazi and Al Bayda. Two years after independence, on 28 March 1953, Libya joined the Arab League.

When Libya declared its independence on 24 December 1951 it was the first country to achieve independence through the United Nations and one of the first former European possessions in Africa to gain independence. The Kingdom of Libya was proclaimed a constitutional and a hereditary monarchy and Idris was proclaimed king. Previously, the USSR had sought a Mandate over Libya following the end of World War II.[18]

Following independence Libya faced a number of problems. There were no colleges in the country and just sixteen college graduates. Also the country had just three lawyers with not a single Libyan physician, engineer, surveyor or pharmacist in the kingdom. It was also estimated that only 250,000 Libyans were literate and that 5% of the population was blind, with eye diseases such as trachoma widespread. In light of these Britain provided a number of civil servants to staff the government.

In April 1955, oil exploration started in the kingdom with its first oil fields being discovered in 1959. The first exports began in 1963 with the discovery of oil helping to transform the Libyan economy, although imposing a resource curse on Libya. Although oil drastically improved Libya's finances, popular resentment grew as wealth was increasingly concentrated in the hands of the elite.

On 25 April 1963, the federal system of government was abolished and in line with this the name of the country was changed to the Kingdom of Libya to reflect the constitutional changes.

As was the case with other African nations following independence, the remaining Italian settlers in Libya held many of the best jobs, owned the best farmland and ran the most successful businesses.

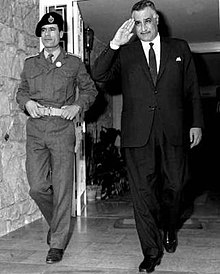

The monarchy came to an end on 1 September 1969 when a group of military officers led by Muammar al-Gaddafi staged a coup d’état against King Idris while he was in Turkey for medical treatment. The revolutionaries arrested the army chief of staff and the head of security in the kingdom. After hearing about the coup, King Idris dismissed it as "unimportant" while it was initially reported (falsely) that the Crown Prince Hasan as-Senussi had announced his support for the new regime.

The coup pre-empted King Idris' instrument of abdication dated 4 August 1969 to take effect 2 September 1969 in favour of the Crown Prince, who had been appointed regent following the king's departure for Turkey. Following the overthrow of the monarchy the country was renamed the Libyan Arab Republic.

Libya under Kaddalfi

On 1 September 1969 a small group of military officers led by then 28-year-old army officer Mu'ammar Abu Minyar al-Qadhafi staged a coup d'état against King Idris, who was exiled to Egypt. The new regime, headed by the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), abolished the monarchy and proclaimed the new Libyan Arab Republic. The new RCC's motto became "freedom, socialism, and unity". It pledged itself to remedy "backwardness", take an active role in the Palestinian Arab cause, promote Arab unity, and encourage domestic policies based on social justice, non-exploitation, and an equitable distribution of wealth.

The new government negotiated with the Americans to evacuate the base from Libya. The Wheelus Air Base agreement had just two more years to run, and in December 1969, the U.S. agreed to vacate the facility by June 1970.

In 1977, Gaddafi renamed the state to Jamahiriya, a neologism translating to "state of the masses". Gaddafi styled himself "Leader and Guide of the Revolution of Libya". Gaddafi also styled himself as an advocate of Pan-Africanism, and was active in the establishment of the African Union in 2001. H used to give himself titles such as "King of Kings", "leader of the Arab leaders" and "imam of the Muslims" (at the 2009 Arab League Summit).

Gaddafi stepped down as General Secretary of the General People's Committee in 1977, being succeeded by Abdul Ati al-Obeidi. However, he remained in autocratic control of the country as de-facto dictator, as he retained full control over the Libyan Armed Forces.

Gaddafi undertook a number of military adventures during the 1970s to 1980s, including the Chadian–Libyan conflict, the Libyan–Egyptian War and the Gulf of Sidra incident (1981). He introduced the Pan-African Legion in 1972, a Libyan-sponsored pan-Arab paramilitary force by means of which Gaddafi aspired to establish a "Great Islamic State of the Sahel". His open endorsement of terrorism led to the Reagan administration declaring Libya a "state sponsor of terrorism" on December 29, 1979, and eventually culminated in the 1986 US Bombing of Libya.

The 1986 bombing of Libya was a turning-point in Gaddafi's approach to the foreign relations of Libya. Gaddafi stopped endorsing terrorist attacks on western countries, and while his behaviour remained extremely erratic, occasionally provoking international incidents such as the HIV trial in Libya and the Swiss-Libyan diplomatic crisis, Gaddafi managed to improve his image in the west and by the early 2000s had mostly benign relations with western democracies.

2011 Uprising

In February 2011, anti-government mass protests sprang up against Gaddafi in Benghazi and other towns of Libya, in the context of the wider 2010–2011 Middle East and North Africa protests. On 18 February demonstrators took control of Benghazi, the second largest city of Libya, with some support from police and military units. In reaction the government sent elite troops, which were resisted by Benghazi's inhabitants and mutineering members of the military.[19] In Benghazi, during the course of four separate protests that took place on 20 February, more than 200 people have died.[20] The New York Times reported that "the crackdown in Libya has proven the bloodiest of the recent government actions."[21]

On March 10, 2011 France became the first nation to recognize the National Transition Council of the anti-government rebels as the sole Representative of Libya. An Élysée source also announced that France plans to send an ambassador to Benghazi. Nations who recognize the Council as the government of Libya may not have to go through the process of obtaining UN security council's approval to establish a "No-fly zone" if the Council requests one, as this could count as a "friendly request".[22]

Notes

- ^ a b c Nelson & Nyrop (1987). "Libya: Early History".

- ^ Morony, Michael G. (2003) Manufacturing and Labour Ashgate, Aldershot, Hant, England, p. 245, note 77, ISBN 0-86078-707-9

- ^ a b Weiss, Bernard G. and Green, Arnold H.(1987) A Survey of Arab History American University in Cairo Press, Cairo, p. 129, ISBN 977-424-180-0

- ^ Ballais, Jean-Louis (2000) "Chapter 7: Conquests and land degradation in the eastern Maghreb" p. 133 In Barker, Graeme and Gilbertson, David (2000) The Archaeology of Drylands: Living at the Margin Routledge, London, Volume 1, Part III - Sahara and Sahel, pp. 125-136, ISBN 978-0-415-23001-8

- ^ Bovill, E. W. (1958) The Golden Trade of the Moors Oxford University Press, London, pp. 58-59 OCLC 9462004

- ^ Photos and data about the Italian conquest of Libya (in Italian)

- ^ a b Bertarelli (1929), p. 206.

- ^ Bertarelli (1929), p. 419.

- ^ Sarti, p196.

- ^ 30000 Libyans fought for Italy in WWII

- ^ Chapter Libya (in Italian)

- ^ Economic development of Italian Libya

- ^ Photo of a new Village

- ^ Selent, pp. 20-21

- ^ a b Shields, Jacqueline."Jewish Refugees from Arab Countries" in Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ Stillman, 2003, p. 145.

- ^ History of the Jewish Community in Libya". Retrieved July 1, 2006

- ^ Stalin: Court of the Red Czar, Simon S. Montefiore, 2003

- ^ Bloodshed as tensions rise in Libya

- ^ "Libya: Anti-Gaddafi protests spread to Tripoli". BBC News. February 20, 2011. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (February 20, 2011). "Libyan Forces Again Fire on Residents at Funerals". New York Times. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "France grants official recognition to rebel Libyan national council", Ha’aretz, IL

{{citation}}:|section=ignored (help).

Bibliography

- Bruce St John, Ronald (2006). Historical dictionary of Libya. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-5303-5.

- Chapin Metz, Hellen (1987). Libya: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress.

- Nelson, Harold D. (1987). Libya: A Country Study. Library of Congress Country Studies. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. OCLC 5676518.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Wright, John L. (1969). Nations of the Modern World: Libya. Ernest Benn Ltd.

- Bertarelli, L.V. (1929). Guida d'Italia, Vol. XVII (in Italian). Milano: Consociazione Turistica Italiana.