History of Washington & Jefferson College

The history of Washington & Jefferson College begins with three log cabin colleges established by three frontier clergymen in the 1780s: John McMillan, Thaddeus Dod, and Joseph Smith. The three men, all graduates from the College of New Jersey, came to present-day Washington County to plant churches and spread Presbyterianism to what was then the American frontier beyond the Appalachian Mountains. John McMillan, the most prominent of the three founders because of his strong personality and longevity, came to the area in 1775 and built his log cabin college in 1780 near his church in Chartiers. Thaddeus Dod, known as a keen scholar, built his log cabin college in Lower Ten Mile in 1781. Joseph Smith taught classical studies in his college, called "The Study" at Buffalo.

Washington Academy was chartered by the Pennsylvania General Assembly on September 24, 1787. The first members of the board of trustees included Reverends Dod and Smith. After a difficult search for a headmaster, in which the trustees consulted Benjamin Franklin, the trustees unanimously selected Thaddeus Dod, considered to be the best scholar in western Pennsylvania. Amid financial difficulties and unrest from the Whiskey Rebellion, the academy held no classes from 1791 to 1796. In 1792, the academy secured four lots at Wheeling and Lincoln street from William Hoge and began construction on the stone Academy Building. During the Whiskey Rebellion, portions of David Bradford's militia camped on a hillside that would later become home to the unified Washington & Jefferson College.

In October 1792, after a year's delay from its official incorporation resulting from "trouble with Indians," McMillan was chosen as the headmaster and Canonsburg was chosen as the location for the "Canonsburg Academy." At a subsequent unknown date, McMillan transferred his students from the log cabin to Canonsburg Academy. Canonsburg Academy was chartered by the General Assembly on March 11, 1794, thus placing it firmly ahead of its sister school, Washington Academy, which was without a faculty, students, or facilities. On January 15, 1802, with McMillan as president of the board, the General Assembly finally granted a charter for "a college at Canonsburgh."

In 1802, Canonsburg Academy was reconstituted as Jefferson College, with John McMillan serving as the first President of the board of trustees. In 1806, Matthew Brown petitioned the Pennsylvania General Assembly to grant Washington Academy a charter, allowing it to be re-christened as Washington College. At various times over the next 60 years, the various parties within the two colleges pursued unification with each other, but the question of where the unified college would be located thwarted those efforts. In 1817, a disagreement over a perceived agreement for unification erupted into "The College War" and threatened the existence of both colleges. In the ensuing years, both colleges began to undertake risky financial moves, especially over-selling scholarships. Thanks to the leadership of Matthew Brown, Jefferson College was in a stronger position to weather the financial storm for a longer period. Desperate for funds, Washington College accepted an offer from the Synod of Wheeling to take control of the college, a move that was supposed stabilized the finances for a period of time. However, Washington College then undertook another series of risk financial moves that crippled its finances.

Following the Civil War, both colleges were short on students and short on funds, causing them to join as Washington & Jefferson College in 1865. The charter provided for the college to operate at both Canonsburg and Washington, a position that caused significant difficulty to the administration trying to rescue the college amid ill feelings over the unification. In 1869, the two-campus arrangement was declared a failure and all operations were moved to Washington. However, a lawsuit from Canonsburg residents and Jefferson College partisans seeking to overturn the consolidation was filed and eventually made its way to the United States Supreme Court. By 1871, the Supreme Court upheld the consolidation, allowing the newly configured college to proceed. Under James D. Moffat, the college experienced a period of growth. The tenure of Simon Strousse Baker between 1922 and 1931 saw a large amount of construction, as well as student unrest that led to his resignation. During World War II, the college opened its doors to the United States Army as a training facility and subsequently admitted a large number of veterans, which swelled the student body to record levels. In 1970, the board of trustees voted to admit women for the first time in the college's history. Under Brian C. Mitchell, who served as president from 1998 to 2004, the college again a growth in construction and an effort to improve relations with the neighboring communities. In 2004, Tori Haring-Smith became the first woman to serve as president of Washington & Jefferson. She focused on internationalizing the campus by recruiting more international students and creating the Magellan program, which sends students abroad to pursue independent study during the summer. She also built the Swanson Science Center and the Ross Family Athletic Center. During her tenure, she raised more than $250 million for endowment, faculty, scholarships, athletics, academic programs, and the physical plant. She retired in 2017.

Three log colleges[edit]

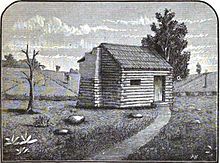

Washington & Jefferson College traces its origin to three log cabin colleges established by three frontier clergymen in the 1780s: John McMillan, Thaddeus Dod, and Joseph Smith.[1] The three men, all graduates from the College of New Jersey, came to present-day Washington County to plant churches and spread Presbyterianism to what was then the American frontier beyond the Appalachian Mountains.[1] They were "men of like minds, who worked in harmony like a brotherhood," even though they had different personalities.[1] McMillan was the executive, Dod the scholar, Smith the revivalist.[1]

The early students were subjected to regular attacks by local Indian tribes and were greatly influenced by religious revivals and the Second Great Awakening.[1] The women of "the 5 congregations" (Bethel, Buffalo, Chartiers, Cross Creek, and Ten Mile) had a tradition of making clothes for the students, most of whom were farmers and many were veterans of the Revolution.[1] Most attended school to prepare for the ministry, and many students pushed west to spread the Gospel to other frontiersmen and often the same Indians that were attacking them.[1] These three log colleges were not rivals, as many students moved from school to school to relieve the burden of the three ministers, each of whom had other duties.[2]

John McMillan, the most prominent of the three founders because of his strong personality and longevity, came to the area in 1775 and built his log cabin college in 1780 near his church in Chartiers.[1] In addition to his pastoral duties, he taught a mixture of mature college-level students and some elementary students.[1] James McGready, who would later play an important role in the Second Great Awakening, studied Latin under McMillan in 1783.[1] The original cabin was destroyed by fire, but rebuilt by McMillan in the late 1780s.[1][3] This log school has been preserved, and is located beside the Middle School in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania.[1][3] Thaddeus Dod built his log cabin college in Lower Ten Mile in 1781.[1] He taught his students math, ancient languages, and the classics.[4] His students also studied the frontier and encountered local Indians.[4][5] Joseph Smith taught classical studies in his college, called "The Study" at Buffalo[5]

Washington Academy[edit]

Largely resulting from the lobbying efforts of Reverend McMillan and two of his elders, Judge James Allison and Judge John McDowell, Washington Academy was chartered by the Pennsylvania General Assembly on September 24, 1787, providing for the "education of youths in useful arts, sciences and literature.[6] The first members of the board of trustees included these three men, as well as Reverends Dod and Smith.[6] The board quickly secured a land grant of 5,000 acres (20 km2) north of the Ohio River and west of Allegheny River (present-day Beaver County) from the Secretary of the Land Office.[6] This tract of land, secured from the Lenape and Wyandot in the Treaty of Fort McIntosh, was subject to competing claims resulting from poorly executed grants.[6] The land, impractically distant from Washington County, was gradually sold off for funds.[6] After a difficult search for a headmaster, in which the trustees consulted Benjamin Franklin, the trustees unanimously selected Thaddeus Dod, considered to be the best scholar in western Pennsylvania.[6] Instruction began on April 1, 1789, in the upper room of the log courthouse in Washington.[6]

In 1790, a courthouse fire left the academy without a home.[6] Amid financial difficulties and unrest from the Whiskey Rebellion, the academy held no classes from 1791 to 1796.[6] The trustees continued to meet and named David Redick to succeed Dod as headmaster.[6] In 1792, the academy secured four lots at Wheeling and Lincoln street from William Hoge.[6] A building was constructed there, with the foundation and walls completed in 1793.[6] The building survives to this day, in a slightly different location, as McMillan Hall, the eighth-oldest academic building in continuous use in the nation.[6]

Early trustees found themselves on opposite sides of the Rebellion, with Reverend McMillan and James Ross supporting the Federal cause; David Bradford, the leader of the rebellion, was joined by Judge Allison, Judge McDowell, and James Marshall.[6] Of the seventeen members of Bradford's militia captured by federal troops and marched to Philadelphia for trial, Reverend John Corbley was an original Washington Academy trustee and Colonel John Hamilton served as a Jefferson trustee for 29 years.[6] Portions of Bradford's militia camped on a hillside that would later become home to the unified Washington & Jefferson College.[6]

The academy reopened in late spring 1796 and received a donation of $3,000 complete from the General Assembly to teach 10 indigent students for two years.[6] In 1805 Matthew Brown took the position of Principal and pastor of the First Presbyterian Church.[6][7] He brought his protege David Elliott from Mifflin, Pennsylvania to become a teacher, giving the academy a new vibrancy that had been missing.[6][7]

Canonsburg Academy[edit]

In October 1791, Reverend Joseph Smith became Moderator of the Virginia Synod amid a push to develop a school to train Presbyterian ministers for the west.[8] Several locations were considered, including Washington, Canonsburg, and the McMillan's log cabin.[6] In October 1792, after a year's delay from its official incorporation resulting from "trouble with Indians," McMillan was chosen as the headmaster and Canonsburg was chosen as the location for the "Canonsburg Academy."[8] At McMillan and Matthew Henderson's request, Col. John Canon donated land near town center for the academy and financed the building of a 2-story stone school house.[8] Other operating funds were raised by the circulation of subscription lists to local residents, especially among McMillan's congregants.[8] At an unknown date, McMillan and Ross transferred their students from the log cabin to Canonsburg Academy.[8] Canonsburg Academy was chartered by the General Assembly on March 11, 1794, thus placing it firmly ahead of its sister school, Washington Academy, which was without a faculty, students, or facilities.[8]

In 1796, Canonsburg trustees began petitioning the General Assembly to consider chartering the academy as the first college beyond the Alleghenies.[8] Another petition followed in 1798, asking for funds from the General Assembly.[8] While the academy was founded under the auspices of the Presbyterian church to train frontier ministers, the advertisements and petitions to the state emphasised its liberal arts offerings over its theological training.[8] Another petition to the General Assembly in October 1798 focused on the low tuition and the fact that facilities were already constructed.[8] In 1800, the General Assembly appropriated $1,000 to the academy.[8] On January 15, 1802, with McMillan as president of the board, the General Assembly finally granted a charter for "a college at Canonsburgh."[8]

Jefferson College[edit]

Organization, early development, and The College War[edit]

On April 29, 1802, Jefferson College was organized by the newly chartered board of trustees.[9] It was named after Thomas Jefferson, who sent a letter of thanks to the college and a portrait of himself as a gift.[10][nb 1] John McMillan served as first President of the board of trustees; during the first 25 years of Jefferson College's existence, McMillan served in almost every possible role, including acting Principal and Vice-Principal of the college, professor, college pastor, and treasurer.[9] Of the 21 original board members, only 8 were clergymen.[12] The Jefferson Board was remarkably stable, with only 5 men serving as President of the Board between 1802 and 1865.[12] On August 29, 1802, John Watson, who was personally tutored by McMillan and was his son-in law, was elected as the first President of Jefferson College.[10] After Watson died that November, McMillan took over the daily operations of the college.[10] In April 1803, James Dunlap was elected as Watson's successor.[12] He was well liked and guided the college through difficult times, including the burgeoning rivalry with Washington College.[12] The new college maintained a preparatory department, now called Jefferson Academy, to train pre-college students in the principles of Greek, Latin, composition, grammar, oratory, and arithmetic.[13] In 1807, the Washington College Board approached the Jefferson Board with a proposal to appoint committees for the purpose of devising a plan for the union of the two institutions.[14] This attempt failed over disagreement over selecting a site for the united institution.[14] Dunlap resigned the Presidency in 1811 and was replaced by 23-year-old minister Andrew Wylie, who was an 1810 graduate of Jefferson College and was considered to be one of the most educated men in the area.[14][15][16] During his tenure, Wylie expanded the curriculum, adding the study of chemistry, and purchased a lot from Mrs. Canon for expansion.[16]

Wylie was in favor of entering into a union with Washington College, provided that the terms favored Jefferson.[16] On October 25, 1815, two committees, one from each institution, met at Graham's tavern and negotiated a deal for the union of the two colleges.[16] The deal called for the final placement of the institution in Washington, with the majority of the trustees and faculty coming from Jefferson.[16] However, by 1817, the deal fell apart misunderstandings and accusations from alumni and partisans on each side, causing Jefferson to cancel the union.[16] The recriminations and hurt feelings caused the incident to be called "The College War."[16] Because of that, Wylie resigned the Presidency and John McMillan once again took over daily operation of Jefferson College.[16]

William McMillan, who was a member of Jefferson College's first graduating class in 1802 and John McMillan's nephew, was elected president on September 24, 1817.[17][18] He was grave and stern, but not well liked by students and unable to deal with the problems facing the college.[18] In 1922, five students were brought up on charges of inciting "sedition and rebellion in College" by being "venters and circulators of calumny and slander against the character and reputation of the Principal of this College."[18] These students had signed a petition from members of the Philo and Franklin Literary Societies alleging that McMillan was an inadequate teacher and speaker.[18] In a related charge, another student was accused of writing an article making light of certain religious organizations and scholarships funded by presbyteries.[18] The trustees declined to pursue the matter and McMillan resigned his office.[18] This incident represented a significant step towards the secularization of the college, as before, earlier students would not have questioned the efficacy of a learned clergyman, nor satirized a religious organization.[18]

Prosperity under Matthew Brown[edit]

In 1822, Matthew Brown, who had been Andrew Wylie's counterpart at Washington College during The College War, was pressured to leave because some prominent families in Washington were uncomfortable with his growing influence, as the president of Washington College and as pastor of First Presbyterian Church.[19] Brown had accepted a position as President of Centre College, but Rev. Samuel Ralston, who was president of the board of trustees, convinced him to take the Presidency of Jefferson College instead.[20] He was installed on graduation day and gave a well-received impromptu commencement address.[19] Ironically, the two Presidents who had been on opposite sides of The College War, then found themselves at the helm of the other institution, a fact that pleased Jefferson's partisans, who were still sore over Washington's hiring of Wylie.[19]

Brown's tenure was a prosperous one for Jefferson College, with the college graduating 3 times the number of graduates as during his predecessor's tenure.[19] His strong leadership style, which had caused friction at Washington College, was well received in Canonsburg.[19] Providence Hall was completed in 1832, providing the necessary space for the growing student body.[19] In 1817, Brown organized a girls' academy, similar to the Washington Female Seminary that was later founded in Washington.[19][21] This school, while operated as a separate institution, was probably closer to private tutoring provided by Brown and an assistant named Mr. Williams.[22] By this time, Western Pennsylvania was no longer the frontier of the nation, and the National Road, which ran through Washington, allowed for a closer connection to the eastern colleges.[19] Jefferson also began to attract a number of southern students, partly because of the improved transportation and because Jefferson was more well known that Washington, which had fallen on hard times.[19] In 1830, the college purchased a farm where students could work several hours a day to earn tuition money.[19] By 1832, 26 students were supporting themselves in this way.[19] The farm was sold in 1846 when it became clear that the farm couldn't be expanded and the trustees wanted to put that money to use elsewhere.[19] In 1832, the trustees began a scholarship system to pay tuition, where a donor could donate $150 to educate a single student or $1,000 for a perpetual scholarship.[19] This system would eventually spiral out of control and endanger the college, as overzealous trustees began selling scholarships that were good for several generations even though the funds would have long run out.[19]

Jefferson Medical College[edit]

During the early 19th century, several attempts to create a second medical school in Philadelphia had been stymied, largely due to the efforts of University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine alumni[23] In an attempt to circumvent that opposition, a group of Philadelphia physicians led by Dr. George McClellan sent a letter to the trustees of Jefferson College in 1824, asking the college to establish a medical department in Philadelphia.[24] The trustees agreed, establishing the Medical Department of Jefferson College in Philadelphia.[24] In spite of a vigorous challenge, the Pennsylvania General Assembly granted an expansion of Jefferson College's charter in 1826, endorsing the creation of the new department and allowing it to grant medical degrees.[24][25] An additional 10 Jefferson College trustees were appointed to supervise the new facility from Philadelphia, owing to the difficulty of managing a medical department on the other side of the state.[24] Two years later, this second board was granted authority to directly manage the Medical Department, while the Jefferson College trustees maintained veto power for major decisions.[24]

The first class was graduated in 1826, receiving their degrees only after the resolution of a lawsuit from Penn alumni seeking to close the school.[24] The first classes were held in the Tivola Theater on Prune Street in Philadelphia, which had the first medical clinic attached to a medical school.[26] Jefferson College retained the right to select 10 of its graduates every year to attend the Medical College free of charge.[19] Owing to the teaching philosophy of Dr. McCellan, classes focused on clinical practice.[26] In 1828, the Medical Department moved to the Ely Building, which allowed for a large lecture space and the "Pit," a 700-seat amphitheater to allow students to view surgeries.[26] This building had an attached hospital, the second such medical school/hospital arrangement in the nation, servicing 441 inpatients and 4,659 outpatients in its first year of operation.[26] Jefferson College considered Jefferson Medical College graduates to be alumni.[19] The relationship with Jefferson College survived until 1838, when the Medical Department received a separate charter, allowing it operate separately as the Jefferson Medical College.[25][27] Through several phases of expansion and growth, the Jefferson Medical College grew into Thomas Jefferson University, a private health sciences university with over 2,000 students.

Decline prior to union with Washington College[edit]

Robert Jefferson Breckinridge was elected President of Jefferson College on January 2, 1845.[28] He was a pious Presbyterian preacher and a well-respected orator.[29] With his Kentuckian background, he was able to understand the increasingly Southern student body, which grew under his leadership.[29] His health suffered during the Pennsylvania winters, and he resigned in 1847, leaving a large part of his library to the school.[29]

Alexander Blaine Brown, the son of Matthew Brown, was elected to be Breckinridge's successor.[30] Even though the students had petitioned the board of trustees to name a prominent scholar, suggesting William Holmes McGuffey, Brown's election was well received, as he had been a well liked professor at Jefferson.[30] His term was generally successful, graduating 50 to 60 graduates each year by the end of his term.[30] Notably, the Synod of Pittsburgh offered to supervise Jefferson, as had been done by the Wheeling Presbytery for Washington College.[30] The board of trustees declined the offer, not wishing to cede control of the college's affairs to any single religious institution, especially since many of the college's leaders were from disparate Presbyteries, and because they had seen the changes that took place at Washington College after it accepted a similar offer from the Synod of Wheeling.[30][31]

It is true that the Institution has always been predominantly Presbyterian in its character, from the fact that it was originally planted in the midst of a population almost exclusively Presbyterian, and has always been dependent chiefly on Presbyterian patronage. This character it is expected still to maintain. Its Presbyterianism, however, has never been exclusive or sectarian. At least three branches of the great Presbyterian family, all holding "the like precious faith" have always been united in its support. For one of these denominations, largely in the majority, to usurp the exclusive control of an institution in which the others are alike interested, in proportion to their numbers, would be a gross violation of good faith and Christian courtesy.

— Trustees of Jefferson College, Responding to Synod of Pittsburgh's offer to supervise Jefferson College[30]

On January 7, 1847, Joseph Alden was elected President of Jefferson College.[32] A well liked professor, he was likely a better teacher than administrator, but many of the problems he faced were national or began well before he took office.[33] The college's enrollment and endowment levels were high during the early part of his tenure, but the growing conflict between the North and the South prevent many Southern students from continuing their studies, causing the number of graduating students to fall from 75 to 45 by the end of his term.[32] In 1860, the board finally stopped the practice of selling perpetual scholarships, but only after the program had devastated the college's finances.[33] By the end of his term, Jefferson College was in dire straits.[33] It was left to his successor, David Hunter Riddle, Matthew Brown's son-in-law, to effectuate the union with Washington College.[34]

Use of former Jefferson College facilities[edit]

The former Jefferson College facilities in Canonsburg were later used for an academy.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2012) |

Washington College[edit]

Chartering and early history[edit]

In 1806, Matthew Brown and Parker Campbell, head of the Washington County bar successfully petitioned the Pennsylvania General Assembly to grant Washington Academy a charter.[7] It was only through the tireless work of Brown and David Elliott, who had improved Washington Academy's academic standards beyond what was expected of an academy, that the charter was ever issued, because of Jefferson's close proximity.[7] The charter was granted on March 28, 1806.[7] Of the 21 original board of trustees, only 4 were clergymen.[35] One of them was John Anderson, who had succeeded James McGready as headmaster of Thaddeus Dod's log school cabin in Buffalo.[36]

During Brown's tenure as President of the new college, the relationship between First Presbyterian Church was strong, as he was the leader of both organization; it has served as the de facto college church ever since.[37] The fact that he held two positions of authority within the community, as well as personal conflicts, raised the ire of several prominent families in the community.[7] The Reed family, whose descendants later built the Davis Memorial Hall, supported Brown, while Hoge family, relatives of the town founders, opposed him.[7] That controversy, coupled with the stress of the College War induced him to resign his post at the college, focusing on his pastoral duties.[7]

The College War and aftermath[edit]

In 1817, the college and town were without leaders and encountered difficult times, so they asked Matthew Brown to return to Washington to take his old positions back.[38] He declined, as did several other men who did not wish to take those positions in such a toxic environment.[38] Andrew Wylie, who had been Matthew Brown's rival at Jefferson College during the College War, was named President of Washington College.[38][39] He had hoped to take the pastor position at First Presbyterian Church, but there were still many Brown partisans, who even distributed pamphlets against him.[38] During his largely successful tenure at Washington College, two wings were added to expand the Academy Building in 1818, and he was able to secure a state grant to continue operations.[38] The National Road extended to Washington, causing the town to expand and become more cosmopolitan.[38] In 1827, the board of trustees entered into an agreement to issue medical degrees to graduates of the Washington Medical College in Baltimore, Maryland, which had encountered resistance from Baltimore's existing medical school, University of Maryland School of Medicine.[40][41] While it issued degrees, Washington College did not take a strong leadership role in the development of the medical school.[41] Wylie left the college in 1828, tired from the infighting and local politics in Washington.[38] He followed the advice of his former student and friend, William Holmes McGuffey, and went west to become the founding president of Indiana University.[38]

Following Wylie's exit, Washington College was without a president, First Presbyterian Church was without a pastor, and the long-time President of the Board of Trustees had died.[42] Rev. John Stockton was offered presidency and declined.[42] In 1830, there was no graduation, and the college was in danger of closing.[38] David Elliott, who was pastor at First Presbyterian after having been Matthew Brown's protege, agreed to take the position on a temporary basis.[42] Elliott revived the college, securing money from the state, re-building the faculty, adding English literature to the curriculum, and increasing the student body from 20 in his first year to 120 by the end of his term.[42]

He was able to resign when David McConaughy was elected president in 1831.[43] McConaughy was not a very energetic administrator and was not known to be personally engaged in the affairs of the college, but he was a well-respected scholar, thoughtful counselor, and a competent public figure.[43] During his tenure, the college added faculty members and began the process of constructing the New College, which became possible after McConaughy convinced the town to abandon Cherry Street, which ran in front of the proposed building site.[43] However, the college was in dire need of financial resources and engaged in reckless financial practices, including a scholarship program even more precarious than the one at Jefferson College, having faculty solicit funds in their spare time, and contracting with an agent in Europe to raise funds.[43] Even though the fundraising was successful in the short term, the donations even included nails, stoves, and iron, the practices were not sustainable and would eventually lead to ruin.[43]

The final parcels of the college land in Beaver County was sold off in 1835.[38] On March 3, 1833, Maryland granted the medical school a charter, ending its relationship with Washington College.[41] In 1843, Jefferson College suggested having regular meetings with Washington "on such subjects as may be interesting to both."[43] That year, the two colleges agreed on a simultaneous tuition increase to $15.00 per month.[43] In September 1847, this relationship became codified into a standing committee.[43] The easing tensions between the two colleges was exemplified by Washington awarding Jefferson's president, Alexander Blaine Brown an honorary degree in 1847.[43] In 1850, James Clark became president.[44] He was dedicated to the traditional liberal arts education and merged non-classical departments with the preparatory departments.[44] While he was well liked by the board and the students, he resigned when it became clear that the college would accept the offer from the Synod of Wheeling to take control of the college's affairs.[44] The college had begun preparing for this move since 1850, when it began to have mandatory religious instruction.[31] Beyond any other religious reasons for the decision, the relationship would stabilize the finances of the college. That the Board of Trustees simultaneously pursued union with Jefferson College lends credence to the idea that the relationship with the Synod was of convenience and survival, rather than a strictly ideological move.[45] All non-Presbyterian students were excused from classes on denominational teachings, which was probably the biggest exemption in the nation at a religious college.[31] During this difficult period, marred by declining finances and difficulties in the transition to religious control, it was David Elliott, Samuel J. Wilson, and Brownson who kept the college afloat.[46] James I. Brownson, who was President of the Board of Trustees, took the Presidency as a temporary position to transition the college into religious control, with the express requirement that he would be released from service as soon as a replacement was found.[46] As pastor of the First Presbyterian Church, he was a good friend of the college, and had been baptized by David Elliott.[46] He had hesitated to take the position because he had been a student at Washington and had been taught by most of the faculty members that he was to lead.[46]

Decline prior to union with Jefferson College[edit]

Presbyterian minister John W. Scott was named president in 1852, the same year that the college became affiliated with the Synod of Wheeling.[31] Under the agreement, the Synod had the right to receive an annual report on the status of the college, in addition to the right to nominate faculty members and appoint trustees.[31] The Synod chose stability and generally re-appointed men who had previously held those positions.[31] In exchange, the Synod had an obligation to keep the college solvent with a $60,000 endowment, while the board maintained total control over the college property.[31] In order to fund the new endowment, a new scholarship plan was developed, allowing a family to purchase tuition for 1 son for $50, tuition for all of the family sons for $100, and a perpetual and inheritable scholarship for $200.[31] The measure, which passed the board by a vote of 12 to 4, was able to raise the $60,000 quickly.[31] However, this plan was even more reckless than the earlier scholarship plans, as the rising cost of education far outstripped the money that was generated.[31] Scott was able to lead the college through this period of transition without succumbing to religious sectarianism, as opponents had predicted, and no students were denied admission, nor were faculty members denied positions based on their religion.[31] However, the transition was not without its challenges, as students began to exhibit rebellious attitudes about the new mandatory religious classes and Scott once denounced the student body's "eclectic manner of attending church."[31]

This time period was precarious for the nation, as well, with growing tensions between the North and South made war more and more likely.[31] John W. Scott and many members of the board were strong abolitionists, even to the point where the Washington Examiner newspaper, which was published by two individuals who had been expelled from Washington College, regularly denounced the college for its abolitionist thought.[31] Francis Julius LeMoyne, a trustee and 1815 graduate of Washington College, led the Board's investigation of Professor Richard Henry Lee, a native of Virginia, who was suspected of not selling his family slaves when he was hired by the college.[43] This controversy a marked contrast to what would have happened at Jefferson College, which catered to a southern clientele.[43]

Washington & Jefferson College[edit]

Union[edit]

By 1865, the Jefferson College and Washington colleges faced situation where unification was the only way to survive.[47] Washington College's endowment was roughly $42,000, most of which was invested in government bonds; Jefferson College's endowment totaled roughly $56,000.[48] Both schools were under increased competition with eastern colleges thanks to improved transportation, as well as the stress of the Civil War, which had taken many of their students to battle.[48] Further, the public's willingness to support two institutions of such similar character in such close proximity was wearing thin.[47] Efforts to unify the two colleges, in 1807, 1817, and the 1840s, had traditionally failed because of an inability to agree on a location for the unified institution.[47] Proponents of Washington noted its proximity to the National Road and status as commercial center and county seat.[47] Partisans for Canonsburg argued that their town was more receptive to the college, and pointing to heritage of John McMillan.[47] On November 6, 1863, Dr. Charles Clinton Beatty, head of the Young Ladies' Seminary in Steubenville offered $50,000 to entice the schools to unify.[47] Beatty had a number of familiar and social connections to Washington College, including a stint in leadership of the Synod of Wheeling.[47] The debate among the Boards of Trustees festered for a time, until they were sparked to movement by a meeting on September 27, 1864, of 69 Jefferson and 66 Washington alumni at the First Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh.[47] During the two-day convention, the alumni decided that union was in both schools' best interest, that the unified name should be Washington & Jefferson College, and that it should be non-sectarian, but Protestant in character.[47] The alumni plan called for the final location to be selected by the drawing of lots, with the losing city receiving the preparatory department, the scientific department, and a hoped-for agricultural department.[47]

The Pennsylvania General Assembly granted a charter to the unified institution on March 4, 1865.[47] The final details of the unification differed from the alumni plan.[47] The campus in Canonsburg would house the President, some professors, the sophomore, junior, and senior classes, while the freshmen, Vice President, and some professors would be located in Washington.[47] Board meetings, commencement, and other special events would alternate between the two locations.[47] The unified board would include 15 from each institution with Dr. Beatty as the 31st member.[47] Of the professors, David Hunter Riddle and Alonzo Linn stayed in Canonsburg.[47] The new charter clearly indicated that Washington & Jefferson College would be non-sectarian.[31] On August 1, 1865, former Jefferson president Robert Jefferson Breckinridge was asked to take the presidency, an offer he formally declined that December, due to failing health and the effects from the assassination of his close friend, Abraham Lincoln.[47] The union of the two colleges, one appealing largely to southern students and the other staunchly abolitionist, was sealed just as the Union was preserved.[47]

Struggles with multiple campuses[edit]

Jonathan Edwards, a pastor from Baltimore who had been president of Hanover College was elected the first president of Washington & Jefferson College on April 4, 1866.[49][50] Dr. Beatty and former presidents David Hunter Riddle and David Elliott, gave speeches at his inauguration.[49] Edwards immediately encountered significant challenges, including the difficulties of administering a college across two campuses,[nb 2] as well as old prejudices and hard feelings among those still loyal to Jefferson College or Washington College.[49] Further, a significant portion of the student body was Civil War veterans from both sides.[49]

The institution faced significant financial difficulties as well, as the charter required that 1/3 of the income be spent for the Washington campus and 2/3 to be spent in Canonsburg campus, which left both starved for funds.[49] After the two alumni associations merged on August 7, 1866, they set out to raise $50,000.[49] The effort failed as a result of the hard feelings caused by the merger, as well as the national crisis.[49] In April 1868, Edwards declared the two-campus endeavor to be a failure and recommended that the school be consolidated.[49] On January 19, 1869, the trustees voted to consolidate, leaving the question of the final location open to either Washington, Canonsburg, or anywhere else in the state.[49] The Pennsylvania General Assembly agreed to amend its 1865 charter, giving the board 60 days to choose the final location before the Pennsylvania Governor would be given authority to appoint a commission to choose.[49] A number of localities offered to host the single-campus institution, including Pittsburgh, Kittanning, Uniontown, Wooster, Ohio and Steubenville, Ohio.[49] The board quickly restricted the options to Canonsburg, whose residents offered a $16,000 subscription, and Washington, whose residents offered a $50,000 subscription.[49] During a meeting of the Board of Trustees on April 20, 1869, the members finally achieved the 2/3 majority required on the eighth ballot to place the institution in Washington.[49] Including the $50,000 was Washington, the endowment stood at $198,797.[49] Edwards resigned on April 20, 1869.[50]

This result was necessarily an intense disappointment to Canonsburg, and the Jefferson Alumni. The bitter feeling of regret at Canonsburg, and among the Jefferson alumni, over the loss of the college, only a little assuaged by the provision at once made for establishing an academy in the college buildings, speaks eloquently for the loyalty of that community and of the alumni to their college, and even forbids condemnation of utterances and actions which for some time hindered the progress of the new college.

— Samuel McCormick, College Centennial, 1902.[51]

Union with single campus[edit]

The first term of the unified campus began in September 1869.[52] Washington College graduate and local Presbyterian pastor Samuel J. Wilson was appointed president pro tempore after Edwards' exit.[53] However, the operations were interrupted by a lawsuit from a group of Canonsburg residents and Jefferson College partisans who challenged the closing of the Canonsburg campus by claiming that the action had violated the charter.[52] On January 3, 1870, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that the Board's action was legal, but that decision was appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States.[52] The final decision on that appeal came in December 1871, again ruling that the consolidation was appropriate.[52] The class of 1870 contained only 10 student, with seven graduating from the academic department and three from the developing science department.[52] Further, the two groups of literary societies were merged, a move that greatly helped to smooth hard feelings.[52] In spite of the closing of Jefferson College, the preparatory department continued to operate.[52]

In 1870, George P. Hays became the second president of Washington & Jefferson College.[54][55] As a Jefferson College graduate and Canonsburg native, he was well-acquainted with the delicate local situation.[55] The college was in a weakened state when he arrived, as most students had scattered to other colleges during the campus consolidation and lawsuit, leaving only 75 students.[55] He expanded the scientific department to a four-year program to match the classical department.[55] The $50,000 donation from Washington was used for improvements to Old Main.[55] By the time he left the college in 1881, roughly 185 students were attending classes and the finances were on their way to being stabilized.[55]

Moffatt[edit]

James D. Moffat was elected third president of Washington & Jefferson College on November 16, 1881.[56] During his tenure, the college experienced a period of growth, including a threefold increase in number of professors and new campus buildings.[56] In 1884, the college purchased the land known as the "old fair ground," now used for Cameron Stadium, for the sum of $7,025.[56] The student body agreed to contribute one dollar each term to finance the purchase.[56] The college built a new gymnasium (now the Old Gym) in 1893; Hays Hall was completed in 1903; Thompson Memorial Library opened in 1905; and Thistle Physics Building was completed in 1912.[56] On December 20, 1893, the campus installed an electric lighting system.[56][57] In 1892, the board of trustees granted a request from senior class that they be graduated in cap and gown, establishing that tradition at W&J for all future commencements.[56] In 1910, Moffat refused an extremely large $40,000 donation to the college that had been bequeathed by a graduate, believing that the man's family needed the money more than the college.[58] Moffat personally paid for the 1912 renovations of McMillan Hall.[59] Moffat resigned on January 1, 1915, after 33 years of service, citing his age of 68 years and the responsibilities of his office as factors in his retirement.[56]

In 1912, the Washington & Jefferson Academy was closed.[60]

World War I era[edit]

Hinitt was named president of Washington & Jefferson College on September 23, 1914.[61] He assumed the duties of the presidency on January 4, 1915, and was officially inaugurated June 15, 1915.[61] His tenure as president of W&J was dominated by the United States' entry into World War I.[61] Total college enrollment dropped to 180, a decrease of 50%.[61] The commencement of 1918 was held early to accommodate men who were deployed to Europe, but only 24 were able to attend.[61] Hinitt's commencement sermon that year reflected this reality: "To the Class of 1918, divided on this day, with so many of your men absent in service, I have but this word to say: Fear God and serve your country!" [61] He resigned the presidency of W&J on June 30, 1918, to accept the pastorate of the First Presbyterian Church of Indiana, Pennsylvania.[61]

William E. Slemmons served as President Pro Tem. of Washington & Jefferson College from May 1918 to June 1919.[62] He served as a trustee of the board of trustees for 38 years and on W&J's faculty as adjunct professor of Biblical Literature from 1919 to 1935.[62] He retired from full-time teaching in 1935, but he continued teaching two philosophy courses until his death on September 4, 1939, at the age of 83.[62]

Samuel Charles Black was elected president on April 18, 1919, and was inaugurated October 22, 1919.[63] By the spring of 1920, the college had the largest enrollment in any one year during its history, increasing from the low point during the World War I years to 368 men freshmen.[63] Black took leave of the college for summer of 1921 to marry.[63] While on a honeymoon tour of national parks in Colorado, he became sick and died in Denver on July 25, 1921.[63]

Simon Strousse Baker served as acting president of Washington & Jefferson following the death of Dr. Black, and he was elected president in his own right on January 26, 1922.[64] He was inaugurated on March 29, 1922.[64] During his tenure, the college physical plant of the college underwent extensive renovation and modernization.[64] Modern business methods were adopted and the endowment grew considerably.[64] Also, the college experienced advances in academics.[64] He was sympathetic and well liked by the college's trustees and by "many a townsman."[65] However, the student body felt that Baker was "autocratic" and held an "unfriendly attitude toward the student body as individuals."[64] Specifically, students objected to his policies regarding campus garb and athletics.[66] Baker defended himself, saying that the perceived ill-will towards students was unintentional and a misunderstanding.[64] Nonetheless, the student body held a strike and general walkout on March 18, 1931.[64] Baker had hoped to complete his plans to build a Moffat Memorial building, a chemistry building, and a stadium before retiring.[64] But, in light of the strike, he resigned on April 23, 1931, for health reasons and for "the good of the College."[64] Baker had been in ill health since undergoing a serious operation in 1930.[65] His health and temperament never recovered from the death of his only son, Lieut. Edward David Baker, an aviator who was shot down in France in 1918.[65] The trustees accepted his resignation on May 13, 1931.[64]

Depression and World War II[edit]

Following the resignation of Baker, Ralph Cooper Hutchison was unanimously elected the seventh president of Washington & Jefferson College on November 13, 1931; he was inaugurated on April 2, 1932, making him at 34 years old one of the youngest college presidents in the county.[66][67] Following the contentious tenure of President Baker, Time magazine noted that Hutchinson "pleased nearly everyone."[66] Hutchinson, in his inaugural address, spoke out against the "false, materialistic doctrine" of going to college "because it pays."[66] Instead, he encouraged students to appreciate the oldtime college education, which was "inviting only to those who did not set profit or wealth as their main objectives in life."[66] In an effort to strengthen the college's science department, Hutchison extended and expanded the southern portion of the campus, between East Wheeling and East Maiden Street.[67] This included the construction of the Jesse W. Lazear Chemistry Building and the final absorption of The Seminary.[67] The main seminary building was purchased, renovated, and re-dedicated as McIlvaine Hall.[67] The John L. Stewart Memorial bell tower was added to McIlvaine Hall.[67] The college constructed two buildings, Washington Hall and Jefferson Hall, to house war effort-related projects.[68] The Old Gym housed the Army Administration School, where hundreds of soldiersreceived their "training in classifications."[69] The Reed residence on Maiden Street was purchased for use as a dormitory.[67] The old Seminary dormitory facing East Maiden Street was razed to make more open space.[67] Finally, the campus was re-oriented so the main entrance faced East Maiden Street, to allow tourists on U.S. Route 40 to see the college. The expanded campus was dedicated on October 26, 1940.[67] In 1943, Hutchison was appointed Director of Civilian Defense for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, a cabinet-level position, by Governor Edward Martin for the duration of the war.[67] He also served as director of the Pennsylvania United War Fund Program.[67] President Hutchison resigned May 7, 1945.[67]

Post-war expansion[edit]

James Herbert Case, Jr. was elected president of Washington & Jefferson College on May 4, 1946, and inaugurated October 25, 1946.[70] Fall 1946 saw the largest student body on record, 1047, with 75% of the students veterans of World War II.[70] This influx of students required additional construction, including an expansion of Old Main to allow for additional food service space.[71] The college added a Division of Engineering in the former Catholic Church on the corner of Wheeling and South Lincoln Streets.[70] On October 29, 1949, the college dedicated Mellon and Upperclass Dormitories.[70] In June 1949, the Board of Trustees granted Case a one-year leave of absence to study the problems of small, independent, liberal arts colleges.[70] On March 25, 1950, before the end of his leave, he resigned to take the presidency of Bard College.[70]

In 1950, Boyd Crumrine Patterson assumed the presidency.[68] In that position, he oversaw curriculum revisions, updated admissions standards, and generally enhanced Washington and Jefferson's reputation.[68] All told, 17 buildings were constructed during Patterson's tenure, including the Phi Gamma Delta Fraternity House, the Wilbur F. Henry Memorial Physical Education Center, 10 Greek housing units in the center of campus, the U. Grant Miller Library, the Student Center, the Commons, and two new dormitories.[68] The athletic fields also were improved.[68] In 1952, the college's two war surplus barracks, Washington Hall and Jefferson Hall, were dismantled.[68] During his presidency, the college's endowment expanded from $2.3 million to nearly $11 million.[72]

Co-ed and development[edit]

On December 12, 1969, the board of trustees authorized the admission of women as undergraduate students, to be effective in September 1970.[68] Dr. Patterson retired on June 30, 1970.[68] Howard J. Burnett took office as president of Washington & Jefferson College on July 1, 1970; he was officially inaugurated on April 3, 1971.[73] During that year, W&J admitted its first female students, hired its first female faculty members, and hired a woman to be Associate Dean of Student Personnel.[73] The school also adopted a new academic calendar to include intersession.[73] To celebrate the bicentennial of W&J's founding, Burnett spearheaded the "Bicentennial Development Program," which resulted in the construction of three new buildings on campus: the Dieter-Porter Life Sciences Building, the Olin Fine Arts Center, and the Rossin Campus Center.[73] During Burnett's tenure, the college acquired and renovated the W & J Alumni House, restored and renovated Thompson Memorial and McMillan Halls, added several residence facilities, and opened the Student Resource Center.[73] The college expanded its academic programs to include the Entrepreneurial Studies Program, the Freshman Forum, and cooperative international education programs with institutions in England, Colombia and Russia, and student enrollment grew from 830 in 1970 to 1,100 in 1998.[73]

During the early 1990s, the college was the setting for two feature films. George A. Romero's film, The Dark Half, was filmed on W&J's campus in 1990, with students and faculty serving as extras.[74][75] Burnett retired as president on June 30, 1998.[73] In 1993, Roommates was also filmed on campus.[75][76]

Construction and refocused relationship with City of Washington[edit]

Upon assuming the presidency of Washington and Jefferson College in 1998, Brian C. Mitchell was thrust into a long-simmering schism between the city of Washington, Pennsylvania and the college. During a courtesy visit to local officials early in his tenure, Mitchell was berated by the officials for 45 minutes, blaming the college "for everything that had gone wrong in the last 50 years.”[77][78] In 2000, the college and Franklin & Marshall College, Michigan State University and SUNY Geneseo participated in a collaborative effort sponsored by the Knight Collaborative, a national initiative designed to develop strategies for partnership between colleges and local community revitalization efforts.[79] Shortly thereafter, Washington & Jefferson was awarded a $50,000 grant from the Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation to develop a coherent plan, entitled the "Blueprint for Collaboration," to detail goals and benchmarks for the future to help the college and the city work together on economic development, environmental protection, and historic preservation.[80] The plan included provisions for the college to offer more academic opportunities for the community and to explore moving its bookstore into the downtown area, develop student housing in the downtown area, and to expand student use of the downtown eating, shopping, and visiting destinations.[79] The City of Washington began a downtown revitalization project featuring new sidewalks, landscaping, and fiber-optic cables.[79] The plan also called for an "investors roundtable," comprising federal and state officials, the banking community, commercial interests, and potential investors.[79] Mitchell ushered in an expansion of the academic programs, including the addition of an Environmental Studies Program, an Information Technology Leadership Program, the Office of Life-Long Learning, the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, and a Bachelor of Arts Degree Program in Music.[81] The college's international partnership and student exchange with the University of Cologne was expanded.[81] A capital campaign brought in over $90 million and the college simultaneously increased the volume of applications and became more selective in its admission practices.[82] In June 2001, Mitchell and the Washington and Jefferson trustees adopted a new master plan to remodel the campus and its educational environment, building modifications and a campus beautification program.[81] The campus dining facility, the "Commons", was remodeled in 2000, the football field was improved and rededicated as Cameron Stadium in 2001, and the Old Gym was re-purposed as a campus fitness and wellness center.[81] Several new buildings were constructed under the plan, including The Burnett Center in 2001, a new technology center in 2003, and a new dormitory in 2002.[81] A second dormitory was initiated in 2003 and was completed after Mitchell's March 2004 departure for the presidency of Bucknell University.[81]

In 2008, the college created the Combat Stress Intervention Program, a research project funded by the U.S. Department of Defense.[83]

Notes[edit]

- ^ That portrait, along with a portrait of Ben Franklin donated by one of his descendants, were stored at the Roberts House until the 1930s, when they were sent to the Jefferson Medical College.[11]

- ^ A rail line between Canonsburg and Washington wasn't constructed until 1871.[49]

References[edit]

- Coleman, Helen Turnbull Waite (1956). Banners in the Wilderness: The Early Years of Washington and Jefferson College. University of Pittsburgh Press. OCLC 2191890.

- ^ Maguire, J. Simonson (1910). "The First Washington". The National Magazine. Vol. 32. Boston: Chapple Publishing Company. pp. 706–711.

- ^ a b Canonsburg's Log Cabin Preservation Project Archived 2010-09-18 at the Wayback Machine, adapted from an article in Jefferson College Times, December 2004, by James T. Herron, Jr.

- ^ a b Wickersham, James (1886). A History of Education in Pennsylvania, Private and Public, Elementary and Higher. Lancaster, Pennsylvania: Inquirer Publishing Company. pp. 400–401.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Coleman 1956 p. 102-107

- ^ Coleman 1956 p. 250

- ^ Coleman 1956 p. 87

- ^ a b c "James Dunlap (1803-1811)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012.

- ^ "Andrew Wylie (1812-1816)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ "William McMillan (1817-1822)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012.

- ^ "Matthew Brown (1822-1845)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012.

- ^ Creig, Alfred (1870). "Presbyterian Church". History of Washington County: from its first settlement to the present time. p. 228.

- ^ Coleman 1956 p. 252

- ^ "George McClellan, Founder". A Brief History of Thomas Jefferson University. Thomas Jefferson University. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ^ a b c d e f Pedrick, Alexander K. (1898). "The Jefferson Medical College of Philadelphia". Charitable Institutions of Pennsylvania. Vol. 1. State Printer of Pennsylvania. pp. 177–202.

- ^ a b "Establishing a School". A Brief History of Thomas Jefferson University. Thomas Jefferson University. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ^ a b c d "Early Homes". A Brief History of Thomas Jefferson University. Thomas Jefferson University. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ^ Medical Society of the State of Pennsylvania, ed. (September 1915). "Jefferson Medical College". The Pennsylvania Medical Journal. Vol. 18. p. 950.

- ^ "Robert J. Breckinridge (1845-1847)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on 2012-07-18. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Coleman 1956 p. 133-142

- ^ a b "Joseph Alden (1857-1862)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Coleman 1956 p. 108

- ^ Coleman 1956 p. 104

- ^ "Andrew Wylie (1817-1828)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013.

- ^ Steiner, Bernard (1894). "Chapter X. Other Professional Schools". History of Education in Maryland. United States Government Printing Office. pp. 286–291.

- ^ a b c Coleman 1956 p. 114-115

- ^ Coleman 1956 p. 134

- ^ a b "Jonathan Edwards (1866-1869)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved 2010-06-03.

- ^ Coleman 1956 p. 154

- ^ "Samuel J. Wilson (Pro Tem. 1869)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012.

- ^ "George P. Hays (1870-1881)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "James D. Moffat (1881-1915)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on 2012-07-18. Retrieved 2022-07-10.

- ^ "Discover Student Life at W&J: Freshmen Forum & the U. Grant Miller Library". Washington & Jefferson College. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- ^ "College Refuses $40,000: Washington and Jefferson Believes Widow and Children Need It" (PDF). The New York Times. December 22, 1910.

- ^ "McMillan Hall". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. Archived from the original on 2009-07-17. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ^ "Hays Hall". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. Archived from the original on 2009-08-25. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Frederick W. Hinitt (Pro Tem. 1915-1918)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012.

- ^ a b c "William E. Slemmons (Pro Tem. 1918-1919)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Samuel Charles Black (1919-1921)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Simon Strousse Baker (1922-1931)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on 2010-04-05.

- ^ a b c "Strike Won". Time. 1931-05-25.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e "W. & J.'s Hutchison". Time. 1932-04-11. Archived from the original on October 27, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Ralph Cooper Hutchison (1931-1945)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on 2019-12-16. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Boyd Crumrine Patterson (1950-1970)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on July 24, 2012.

- ^ "Old Gym". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College.

- ^ a b c d e f "James Herbert Case, Jr. (1946-1949)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013.

- ^ "Old Main". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. Archived from the original on 2009-07-17.

- ^ "Boyd C. Patterson, college President, 86". The New York Times. 1988-07-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Howard Jerome Burnett (1970-1998)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04. Archived from the original on 2009-07-16. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ^ Winks, Michael (October 22, 1990). "Romero kicks off star-studded "Dark Half" here". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ a b "W&J hits the silver screen" (PDF). W&J Magazine. Washington & Jefferson College. Winter 2004. p. 23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-09. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ^ "On Location". Observer-Reporter. Washington, Pennsylvania. September 19, 1993. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ Marino, Gigi (September 2004). "What a Ride It Will Be" (PDF). Bucknell World. Bucknell University.

- ^ "Colleges, communities find ways to coexist". CNN.com. Associated Press. 2003-07-14. Archived from the original on 2006-12-23.

- ^ a b c d "College and Community Present Cooperative Plan" (Press release). Washington and Jefferson College. 2002-11-22. Archived from the original on 2006-08-29.

- ^ "Blueprint for Collaboration Applauded" (Press release). Washington and Jefferson College. 2003-06-26. Archived from the original on 2006-08-29.

- ^ a b c d e f "Brian C. Mitchell (1998-2004)". U. Grant Miller Library Digital Archives. Washington & Jefferson College. 2003-09-04.

- ^ "Mitchell leaves W&J for job at Bucknell". Pittsburgh Business Times. 2004-03-02.

- ^ Reeger, Jennifer (May 26, 2008). "Mental health study focuses on Southwestern Pennsylvania troops". Pittsburgh Tribune Review. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

Bibliography[edit]

- Moffat, James D. (1902). "Washington and Jefferson College". In Herbert Baxter Adams (ed.). Contributions to American Educational History. Vol. 33. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. pp. 236–249.

- Smith, Joseph (1854). Old Restone, or Historical Sketches of Western Presbyterianism. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co.

- Centenary Memorial of the Planting and Growth of Presbyterianism in Western Pennsylvania and Parts Adjacent. Pittsburgh: Benjamin Singerly. 1876.

- Smith, Joseph (1857). History of Jeffersoh College: Including an Account of Early "Log-Cabin" Schools, and the Canonsburg Academy. Pittsburgh: J. T. Shryock.

- Moore, Franklin R.; James Irvin Brownson; Thomas Holliday Elliott (1857). Proceedings and addresses, at the semi-centennial celebration of Washington College: held at Washington, Pennsylvania, June 17–19, 1856. J.T. Shryock.

- Creigh, Alfred (1871). History of Washington County (2 ed.). B. Singerly.

- Stotz, Charles M. (1995). The Early Architecture of Western Pennsylvania: A Record of building before 1860. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 1995. ISBN 978-0-8229-3787-6.

- The Centennial Celebration of the Chartering of Jefferson College in 1802. Philadelphia: George H. Buchanan and Company. 1903.