History of archery

The bow and arrow are known to have been invented by the end of the Upper Paleolithic, and for at least 10,000 years archery was an important military and hunting skill, and features prominently in the mythologies of many cultures.

Archers, whether on foot, in chariots and on horseback were a major part of most militaries until about 1500 when they began to be replaced by firearms, first in Europe, and then progressively elsewhere.

Archery continues to be a popular sport; most commonly in the form of target archery, but in some places also for hunting.

Prehistory

Epipaleolithic

Based on indirect evidence, the bow seems to have been invented near the transition from the Upper Paleolithic to the Mesolithic, some 10,000 years ago. The oldest direct evidence dates to 8,000 years ago. The discovery of stone points in Sibudu Cave, South Africa, has prompted the proposal that bow and arrow technology existed as early as 64,000 years ago.[1]

In the Levant, artifacts which may be arrow-shaft straighteners are known from the Natufian culture, (ca. 12,800-10,300 BP) onwards. The Khiamian and PPN A shouldered Khiam-points may well be arrowheads.

The oldest indication for archery in Europe comes from Stellmoor in the Ahrensburg valley north of Hamburg, Germany. They were associated with artifacts of the late Paleolithic (11,000-9,000 BP). The arrows were made of pine and consisted of a mainshaft and a 15-20 centimetre (6-8 inches) long foreshaft with a flint point. They had shallow grooves on the base, indicating that they were shot from a bow.[2]

The oldest definite bows known so far come from the Holmegård swamp in Denmark. In the 1940s, two bows were found there, dated to about 8,000 BP.[3] The Holmegaard bows are made of elm and have flat arms and a D-shaped midsection. The center section is biconvex. The complete bow is 1.50 m (5 ft) long. Bows of Holmegaard-type were in use until the Bronze Age; the convexity of the midsection has decreased with time.

Mesolithic pointed shafts have been found in England, Germany, Denmark, and Sweden. They were often rather long, up to 120 cm (4 ft) and made of European hazel (Corylus avellana), wayfaring tree (Viburnum lantana) and other small woody shoots. Some still have flint arrow-heads preserved; others have blunt wooden ends for hunting birds and small game. The ends show traces of fletching, which was fastened on with birch-tar.

The oldest depictions of combat, found in Iberian cave art of the Mesolithic, show battles between archers.[4] A group of three archers encircled by a group of four is found in Cueva del Roure, Morella la Vella, Castellón, Valencia. A depiction of a larger battle (which may, however, date to the early Neolithic), in which eleven archers are attacked by seventeen running archers, is found in Les Dogue, Ares del Maestrat, Castellón, Valencia.[5] At Val del Charco del Agua Amarga, Alcañiz, Aragon, seven archers with plumes on their heads are fleeing a group of eight archers running in pursuit.[6]

Archery seems to have arrived in the Americas via Alaska, as early as 6000 BCE,[7] with the Arctic small tool tradition, about 2,500 BCE, spreading south into the temperate zones as early as 2,000 BCE, and was widely known among the indigenous peoples of North America from about 500 CE.[8]

Neolithic

The oldest Neolithic bow known from Europe was found in anaerobic layers dating between 7,400-7,200 BP, the earliest layer of settlement at the lake settlement at La Draga, Banyoles, Girona, Spain. The intact specimen is short at 1.08m, has a D-shaped cross-section, and is made of yew wood.[9] European Neolithic fortifications, arrow-heads, injuries, and representations indicate that, in Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Europe, archery was a major form of interpersonal violence.[10] Stone wrist-guards, interpreted as display versions of bracers, form a defining part of the Beaker culture and arrowheads are also commonly found in Beaker graves.

Bronze Age

Chariot-borne archers became a defining feature of Middle Bronze Age warfare, from Europe to Eastern Asia and India. However, in the Middle Bronze Age, with the development of massed infantry tactics, and with the use of chariots for shock tactics or as prestigious command vehicles, archery seems to have lessened in importance in European warfare.[10] In approximately the same period, with the Seima-Turbino Phenomenon and the spread of the Andronovo culture, mounted archery became a defining feature of Eurasian nomad cultures and a foundation of their military success, until the massed use of guns. In China, crossbows were developed, and Han Dynasty writers attributed Chinese success in battles against nomad invaders to the massed use of crossbows, first definitely attested at the Battle of Ma-Ling in 341 BCE.[11]

Ancient history

Ancient civilizations, notably the Persians, Parthians, Indians, Koreans, Chinese, and Japanese fielded large numbers of archers in their armies. Arrows were destructive against massed formations, and the use of archers often proved decisive. The Sanskrit term for archery, dhanurveda, came to refer to martial arts in general. Mounted archers were used as the main military force for many of the equestrian nomads, including the Cimmerians and the Mongols.

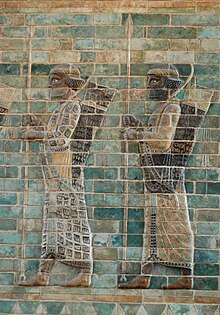

Ancient Near East

The ancient Egyptian people took to archery as early as 5,000 years ago. Archery was widespread by the time of the earliest pharaohs and was practiced both for hunting and use in warfare. Legendary figures from the tombs of Thebes are depicted giving "lessons in archery".[12] Some Egyptian deities are also connected to archery.[13] The "Nine bows" were a conventional representation of Egypt's external enemies. One of the oldest representations of the Nine bows is on the seated statue of Pharaoh Djoser (3rd Dynasty, 27th century BCE).[14]

The Assyrians and Babylonians extensively used the bow and arrow; the Old Testament has multiple references to archery as a skill identified with the ancient Hebrews. Xenophon describes long bows used to great effect in Corduene.

The Chariot warriors of the Kassites relied heavily on the bow. The Nuzi texts detail the bows and the number of arrows assigned to the chariot crew. Archery was essential to the role of the light horse-drawn chariot as a vehicle of warfare.[15]

Three-bladed (trilobate) arrowheads have been found in the United Arab Emirates, dated to 100BCE-150CE.[16]

Greco-Roman antiquity

The people of Crete practiced archery and Cretan mercenary archers were in great demand.[17] Crete was known for its unbroken tradition of archery.[18]

The Greek god Apollo is the god of archery, also of plague and the sun, metaphorically perceived as shooting invisible arrows, Artemis the goddess of hunting. Heracles and Odysseus and other mythological figures are often depicted with a bow.

During the invasion of India, Alexander the Great personally took command of the shield-bearing guards, foot-companions, archers, Agrianians and horse-javelin-men and led them against the Kamboja clans—the Aspasios of Kunar valleys, the Guraeans of the Guraeus (Panjkora) valley, and the Assakenois of the Swat and Buner valleys.[19]

The early Romans had very few archers, if any. As their empire grew, they recruited auxiliary archers from other nations. Julius Caesar's armies in Gaul included Cretan archers, and Vercingetorix his enemy ordered "all the archers, of whom there was a very great number in Gaul, to be collected".[20] By the 4th century, archers with powerful composite bows were a regular part of Roman armies throughout the empire. After the fall of the western empire, the Romans came under severe pressure from the highly skilled mounted archers belonging to the Hun invaders, and later Eastern Roman armies relied heavily on mounted archery.[21]

East Asia

For millennia, archery has played a pivotal role in Chinese history.[22] In particular, archery featured prominently in ancient Chinese culture and philosophy: archery was one of the Six Noble Arts of the Zhou dynasty (1146–256 BCE); archery skill was a virtue for Chinese emperors; Confucius himself was an archery teacher; and Lie Zi (a Daoist philosopher) was an avid archer.[23][24] Because the cultures associated with Chinese society spanned a wide geography and time range, the techniques and equipment associated with Chinese archery are diverse.[25]

In East Asia Joseon Korea adopted a military-service examination system from China,[26] and South Korea remains a particularly strong performer at Olympic archery competitions even to this day.[27][28]

India

The bow and arrow constituted the classical Indian weapon of warfare, from the Vedic period, until the advent of Islam.[29][30] Some Rigvedic hymns lay emphasis on the use of the bow and arrow.[31]

Detailed accounts of training methodologies in early India concern archery, considered to be an essential martial skill in early India.[32] Legendary figures like Drona, are depicted as masters in the art of archery.[33] Arjuna, Eklavya, Karna, Rama, Lakshmana, Bharata and Shatrughna the great warrior are also associated with archery.

Middle Ages

A complete arrow of 75 cm[34] (along with other fragments and arrow heads) dated back to 1283 CE, was discovered inside a cave[35] situated in the Qadisha Valley,[36] Lebanon.

A treatise on Saracen archery was written in 1368. This was a didactic poem on archery dedicated to a Mameluke sultan by ṬAIBUGHĀ, al-Ashrafī.[37]

A 14th century treatise on Arab archery was written by Hussain bin Abd al-Rahman.[38]

A treatise on Arab archery by Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya, Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr (1292AD-1350AD) comes from the 14th century.[39] Another treatise, A book on the excellence of the bow & arrow of c. 1500 details the practices and techniques of archery among the Arabs of that time.[40] An online copy of the text is available.[41]

Skilled archers were prized in Europe throughout the Middle Ages. Archery was an important skill for the Vikings, both for hunting and for war. The Assize of Arms of 1252 tells us that English yeomen were required by law, in an early version of a militia, to practice archery and maintain their skills. We are told that 6,000 English archers launched 42,000 arrows per minute at the Battle of Crecy in 1346.[42] The Battle of Agincourt in 1415 is notable for Henry V's introduction of the English longbow into military lore. Henry VIII was so concerned about the state of his archers that he enjoined tennis and other frivolous pursuits in his Unlawful Games Act 1541.

Decline of archery

The advent of firearms eventually rendered bows obsolete in warfare. Despite the high social status, ongoing utility, and widespread pleasure of archery, almost every culture that gained access to even early firearms used them widely, to the relative neglect of archery.

"Have them bring as many guns as possible, for no other equipment is needed. Give strict orders that all men, even the samurai, carry guns."

— Asano Yukinaga, 1598[43]

In Ireland, Geoffrey Keating (c. 1569 - c. 1644) mentions archery as having been practiced "down to a recent period within our own memory."[44]

Early firearms were inferior in rate of fire (a Tudor English author expects eight shots from the English longbow in the time needed for a "ready shooter" to give five from the musket),[45] and François Bernier reports that well-trained mounted archers at the Battle of Samugarh in 1658 were "shooting six times before a musketeer can fire twice".[46] Firearms were also very susceptible to wet weather. However, they had a longer effective range (up to 200 yards for the longbow, up to 600 yards for the musket),[45][47] greater penetration,[48] and were tactically superior in the common situation of soldiers shooting at each other from behind obstructions. They also penetrated steel armour without any need to develop special musculature. Armies equipped with guns could thus provide superior firepower, and highly trained archers became obsolete on the battlefield. The Battle of Cerignola in 1503 was won by Spain mainly by the use of matchlock firearms, marking the first time a major battle was won through the use of firearms.

The last regular unit armed with bows was the Archers’ Company of the Honourable Artillery Company, ironically a part of the oldest regular unit in England to be armed with gunpowder weapons. The last recorded use of bows in battle in Britain seems to have been a skirmish at Bridgnorth; in October 1642, during the English Civil War, an impromptu militia, armed with bows, was effective against un-armoured musketmen.[49] (A more recent use of archery in war was in 1940, on the retreat to Dunkirk, when Jack Churchill, who had brought his bows on active service, "was delighted to see his arrow strike the centre German in the left of the chest and penetrate his body").[50]

Archery continued in some areas that were subject to limitations on the ownership of arms, such as the Scottish Highlands during the repression that followed the decline of the Jacobite cause, and the Cherokees after the Trail of Tears. The Tokugawa shogunate severely limited the import and manufacture of guns, and encouraged traditional martial skills among the samurai; towards the end of the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877, some rebels fell back on the use of bows and arrows. Archery remained an important part of the military examinations until 1894 in Korea and 1904 in China.

Within the steppe of Eurasia, archery continued to play an important part in warfare, although now restricted to mounted archery. The Ottoman Empire still fielded auxiliary cavalry which was noted for its use of bows from horseback. This practice was continued by the Ottoman subject nations, despite the Empire itself being a proponent of early firearms. The practice declined after the Crimean Khanate was absorbed by Russia; however mounted archers remained in the Ottoman order of battle until the post 1826 reforms to the Ottoman Army. The art of traditional archery remained in minority use for sport and for hunting in Turkey up until the 1820s, but the knowledge of constructing composite bows, fell out of use with the death of the last bowyer in the 1930s. The rest of the Middle East also lost the continuity of its archery tradition at this time.

An exception to this trend was the Comanche culture of North America, where mounted archery remained competitive with muzzle-loading guns. "After... about 1800, most Comanches began to discard muskets and pistols and to rely on their older weapons."[51] Repeating firearms, however, were superior in turn, and the Comanches adopted them when they could. Bows remained effective hunting weapons for skilled horse archers, used to some extent by all Native Americans on the Great Plains to hunt buffalo as long as there were buffalo to hunt. The last Comanche hunt was in 1878, and it failed for lack of buffalo, not lack of appropriate weapons.[52]

Ongoing use of bows and arrows was maintained in isolated cultures with little or no contact with the outside world. The use of traditional archery in some African conflicts has been reported in the 21st century, and the Sentinelese still use bows as part of a lifestyle scarcely touched by outside contact. A remote group in Brazil, recently photographed from the air, aimed bows at the aeroplane.[53] Bows and arrows saw considerable use in the 2007–2008 Kenyan crisis.

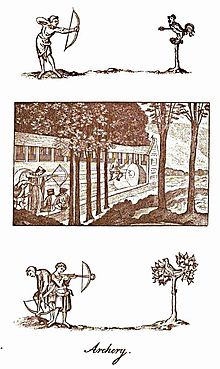

Recreational revival

The British initiated a major revival of archery as an upper-class pursuit from about 1780-1840.[54] Early recreational archery societies included the Finsbury Archers and the Kilwinning Papingo, established in 1688. The latter held competitions in which the archers had to dislodge a wooden parrot from the top of an abbey tower. The Company of Scottish Archers was formed in 1676 and is one of the oldest sporting bodies in the world. It remained a small and scattered pastime, however, until the late 18th century when it experienced a fashionable revival among the aristocracy. Sir Ashton Lever, an antiquarian and collector, formed the Toxophilite Society in London in 1781, with the patronage of George, the Prince of Wales.

Archery societies were set up across the country, each with its own strict entry criteria and outlandish costumes. Recreational archery soon became extravagant social and ceremonial events for the nobility, complete with flags, music and 21 gun salutes for the competitors. The clubs were "the drawing rooms of the great country houses placed outside" and thus came to play an important role in the social networks of local elites. As well as its emphasis on display and status, the sport was notable for its popularity with females. Young women could not only compete in the contests but retain and show off their sexuality while doing so. Thus, archery came to act as a forum for introductions, flirtation and romance.[54] It was often consciously styled in the manner of a Medieval tournament with titles and laurel wreaths being presented as a reward to the victor. General meetings were held from 1789, in which local lodges convened together to standardise the rules and ceremonies. Archery was also co-opted as a distinctively British tradition, dating back to the lore of Robin Hood and it served as a patriotic form of entertainment at a time of political tension in Europe. The societies were also elitist, and the new middle class bourgeoisie were excluded from the clubs due to their lack of social status.

After the Napoleonic Wars, the sport became increasingly popular among all classes, and it was framed as a nostalgic reimagining of the preindustrial rural Britain. Particularly influential was Sir Walter Scott's 1819 novel, Ivanhoe that depicted the heroic character Lockseley winning an archery tournament.[55]

A modern sport

The 1840s saw the first attempts at turning the recreation into a modern sport. The first Grand National Archery Society meeting was held in York in 1844 and over the next decade the extravagant and festive practices of the past were gradually whittled away and the rules were standardised as the 'York Round' - a series of shoots at 60, 80, and 100 yards. Horace A. Ford helped to improve archery standards and pioneered new archery techniques. He won the Grand National 11 times in a row and published a highly influential guide to the sport in 1856.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the sport experienced declining participation as alternative sports such as croquet and tennis became more popular among the middle class. By 1889, just 50 archery clubs were left in Britain, but it was still included as a sport at the 1900 Paris Olympics.

In the United States, primitive archery was revived in the early 20th century. The last of the Yahi Indian tribe, a native known as Ishi, came out of hiding in California in 1911.[56][57] His doctor, Saxton Pope, learned many of Ishi's traditional archery skills, and popularized them.[58][59] The Pope and Young Club, founded in 1961 and named in honor of Pope and his friend, Arthur Young, became one of North America's leading bowhunting and conservation organizations. Founded as a nonprofit scientific organization, the Club was patterned after the prestigious Boone and Crockett Club and advocated responsible bowhunting by promoting quality, fair chase hunting, and sound conservation practices.

In Korea, the transformation of archery to a healthy pastime was led by Emperor Gojong, and is the basis of a popular modern sport. The Japanese continue to make and use their unique traditional equipment. Among the Cherokees, popular use of their traditional longbows never died out.[60]

In China, at the beginning of the 21st century, there has been revival in interest among craftsmen looking to construct bows and arrows, as well as in practicing technique in the traditional Chinese style.[61][62]

In modern times, mounted archery continues to be practiced as a popular competitive sport in modern Hungary and in some Asian countries but it is not recognized as an international competition.[63] Archery is the national sport of the Kingdom of Bhutan.[64]

From the 1920s, professional engineers took an interest in archery, previously the exclusive field of traditional craft experts.[65] They led the commercial development of new forms of bow including the modern recurve and compound bow. These modern forms are now dominant in modern Western archery; traditional bows are in a minority. In the 1980s, the skills of traditional archery were revived by American enthusiasts, and combined with the new scientific understanding. Much of this expertise is available in the Traditional Bowyer's Bibles (see Additional reading). Modern game archery owes much of its success to Fred Bear, an American bow hunter and bow manufacturer.[66]

See also

- Archery

- Kyūdō, Japanese archery

- Yabusame, Japanese horseback archery

- Gungdo, Korean archery

- Turkish archery

- Chinese archery

- Archery in India

References

- ^ Backwell, Lucinda; d'Errico, Francesco; Wadley, Lyn (2008). "Middle Stone Age bone tools from the Howiesons Poort layers, Sibudu Cave, South Africa". Journal of Archaeological Science. 35 (6): 1566–1580. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2007.11.006. "Explicit tests for distinctions between thrown spears and projected arrows have not yet been conducted, and many of the segments could have been employed equally successfully as insets for spears or arrows (Lombard & Pargeter 2008)." Lombard, Marlize; Phillipson, Laurel (2010). "Indications of bow and stone-tipped arrow use 64 000 years ago in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa". Antiquity. 84: 635–648. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00100134.

- ^ McEwen E, Bergman R, Miller C. Early bow design and construction. Scientific American 1991 vol. 264 pp76-82.

- ^ Charles E. Grayson, Mary French, Michael J. O'Brien. Traditional Archery from Six Continents: The Charles E. Grayson Collection. University of Missouri Press 2007. ISBN 978-0-8262-1751-6 p=1

- ^ Keith F. Otterbein, How War Began (2004), p. 72.

- ^ Christensen J. 2004. "Warfare in the European Neolithic", Acta Archaeologica 75, 129–156.

- ^ S.L. Washburn, Social Life of Early Man (1962), p. 207.

- ^ Blitz, John. "Adoption of the Bow in Prehistoric North America. North American Archaeologist, vol 9 no 2, 1988" (PDF).

- ^ Brian Fagan. The first North Americans. Thames and Hudson, London, 2011. ISBN 978-0-500-02120-0 Hodge, Frederick Webb (1907). Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico, Vol 1 pg 485. Government Printing Office

- ^ accessed The oldest Neolithic Bow discovered in Europe, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2012. 1 July 2012

- ^ a b Bronze Age Warfare. Richard Osgood and Sarah Monks with Judith Toms. The History Press 2000. pp.139-142

- ^ Needham (1986), Volume 5, Part 6, 124–128.

- ^ Wilson, John (1956). The Culture of Ancient Egypt pg 186. University of Chicago Press

- ^ Traunecker, Claude (2001). The Gods of Egypt pg 29. Cornell University Press

- ^ "Enemies of Civilization: Attitudes toward Foreigners in Ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China", Mu-chou Poo, Mu-chou Poo Muzhou Pu. SUNY Press, Feb 1, 2012. p. 43. Retrieved 7 jan 2017

- ^ Drews, Roberts (1993). The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe Ca. 1200 B.C. pg 119. Princeton University Press

- ^ "A trilobate arrowhead can be defined as an arrowhead that has three wings or blades that are usually placed at equal angles (i.e. c. 120°) around the imaginary longitudinal axis extending from the centre of the socket or tang. Since this type of arrowhead is rare in southeastern Arabia, we must investigate its origin and the reasons behind its presence at ed-Dur."Delrue, Parsival (2007). "Trilobate Arrowheads at Ed-Dur (U.A.E, Emirate of Umm Al-Qaiwain)"". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 18 (2): 239–250. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0471.2007.00281.x.

- ^ Cambridge University Press (2000). Cambridge Ancient History pg 174.

- ^ Kirk, Geoffrey etc (1993). The Iliad: a commentary pg 136. Cambridge University Press

- ^ The Ashvayanas living on river Guraeus (modern river Panjkora), which are the Gauri of Mahabharata, were also known as Gorys or Guraios, modern Ghori or Gori, a wide spread tribe, branches of which are still to be found on the Panjkora and on both sides of the Kabul at the point of its confluence with Landai (See: History of Punjab, Vol I, 1997, p 227, Publication Bureau, Punjabi University, Patiala (Editors) Dr L. M. Joshi, Dr Fauja Singh). The clan name Gore or Gaure is also found among the modern Kamboj people of Punjab and it is stated that the Punjab Kamboj Gaure/Gore came from the Kunar valley to Punjab at some point in time in the past (Ref: These Kamboja People, 1979, 122; Kambojas Through the Ages, 2005, p 131, Kirpal Singh).

- ^ gutenberg.org Caius Julius Caesar. Caesar's Commentaries. Translated by W. A. Macdevitt.

- ^ Greece and Rome at War, Peter Connolly, Adrian Keith Goldsworthy. Greenhill Books 1998 ISBN 1-85367-303-X ISBN 978-1853673030

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 January 2011. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Six Arts of Ancient China

- ^ Chinese Archery (Paperback). Stephen Selby. Hong Kong University Press 2000. ISBN 962-209-501-1 ISBN 978-962-209-501-4

- ^ The Bows of China. Stephen Selby. Journal of Chinese Martial Studies, Winter 2010 Issue 2. Three-In-One Press, 2010.

- ^ Korea archery at anthromuseum.missouri.edu "During the Choson period (1392-1910), Korea adopted a military-service examination system from China that included a focus on archery skills and that contributed to the development of Korean archery as a practical martial art."

- ^ Archery in South Korea at lycos.com/info/archery

- ^ "South sweep," 28 September 2000 at sportsillustrated.cnn.com

- ^ Zimmer, Heinrich and Campbell, Joseph (1969). Philosophies of India pg 140. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Drews, Robert (1993). The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe Ca. 1200 B.C. pg 119. Princeton University Press

- ^ With the bow let us win cows, with the bow let us win the contest and violent battles with the bow. The bow ruins the enemy's pleasure; with the bow let us conquer all corners of the world. -- Drews, Roberts (1993). The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe Ca. 1200 B.C. pg 125. Princeton University Press

- ^ Scharfe, Hartmut (2002). Education in Ancient India pg 271. Brill Academic Publishers

- ^ Van Buitenen, J. A. B. (1980). The Mahabharata: The Book of the Beginning pg 153. University of Chicago Press

- ^ Abi Aoun B., Baroudy F., Ghaouch A. Khawaja P and alias Momies du Liban: Rapport préliminaire sur la découverte archaéologique de 'Asi-al-Hadat (XIIIe siècle), France, Édifra, 1994

- ^ http://www.cavinglebanon.com/asi-l-hadath-fortified-cave

- ^ http://www.whc.unesco.org/en/list/850

- ^ Boudot-Lamotte, A. 1972. "J. D. Latham et Lt. Cdr. W. F. PATERSON, Saracen Archery, An English version and exposition of a mameluke work on Archery (ca. A.D. 1368), with Introduction, Glossary, and Illustrations, London (The Holland Press) 1970, XL + 219 pp". Arabica. 19, no. 1: 98-99.

- ^ Jallon, A.D. Kitab Fi Ma "Rifat "Ilm Ramy Al-Siham, a Treatise on Archery by Husayn B. "Abd Al-Rahman B. Muhammad B. Muhammad B. "Abdallah Al-Yunini AH 647 (?) - 724, AH 1249-50 (?) - 1324: A Critical Edition of the Arabic Text Together with a Study of the Work in English. University of Manchester, 1980. OCLC: 499854155.

- ^ Ibn Qayyim al-Jawzīyah, Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr. kitab ʻuniyat al-ṭullāb fī maʻrifat al-rāmī bil-nushshāb. [Cairo?]: [s.n.], 1932. OCLC: 643468400.

- ^ Faris, Nabih Amin, and Robert Potter Elmer. Arab archery. An Arabic manuscript of about A.D. 1500, "A book on the excellence of the bow & arrow" and the description thereof. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1945. Translation of "Kitāb fī bayān fadl al-qaws w-al-sahm wa-awsāfihima," no. 793 in Descriptive catalog of the Garrett collection of Arabic manuscripts in the Princeton university library.

- ^ [tuba-archery.com/article/arab-archery.pdf Arab Archery].

- ^ Rhoten, R.: "Trebuchet Energy Efficiency - Experimental Results" AIAA 2006-775

- ^ Asano Yukinaga, 1598 CE, letter to his father, quoted in The Samurai, by S.R. Turnbull, Osprey, London 1977. ISBN 0-85045-097-7

- ^ Geoffrey Keating. The History of Ireland, translated into English and preface by David Comyn, Patrick S. Dinneen. Accessed 9 December 2007

- ^ a b A right exelent and pleasaunt dialogue, betwene Mercury and an English souldier contayning his supplication to Mars: bevvtified with sundry worthy histories, rare inuentions, and politike deuises. wrytten by B. Rich: gen. 1574. Published 1574 by J. Day. These bookes are to be sold [by H. Disle] at the corner shop, at the South west doore of Paules church in London. https://bowvsmusket.com/2015/07/14/barnabe-rich-a-right-exelent-and-pleasaunt-dialouge-1574/ accessed 21 April 2016

- ^ as attributed to Bernier by Dirk H.A. Kolff. Naukar, Rajput, & Sepoy. The ethnohistory of the military labour market in Hindustan, 1450-1860. University of Cambridge Oriental Publications no. 43. Cambridge University Press 1990., p.23

- ^ Korean Traditional Archery. Duvernay TA, Duvernay NY. Handong Global University, 2007

- ^ Gunn, Steven; Gromelski, Tomasz (2012). "For whom the bell tolls: accidental deaths in Tudor England". The Lancet. 380 (9849): 1222–1223. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61702-4. "The mean depth of arrow wounds, for example, was an inch and a half, that of gunshot wounds six inches, not counting balls that went right through the body or head"

- ^ John Norton, letter dated 5 October 1642. As printed in The Garrisons of Shropshire during the Civil War, Leake and Evans publishers, Shrewsbury, 1867, page 32. "every man from 16 to 50 and upwards, gott himself into such armes as they could presently attaine, or could imagine be conduceable for the defence of the towne". "some companies of foote.. with their musketts... began to wade foarde, which being descried, we, with our bowes and arrows did so gaule them (being unarmed men) that with their utmost speed they did retreate" accessed 7 August 2012

- ^ The archer's craft: A sheaf of notes on certain matters concerning archers and archery, the making of archers' tackle and the art of hunting with the bow. Adrian Eliot Hodgkin. Faber 1951

- ^ T.R. Fehrenbach. Comanches, the history of a people. Vintage Books. London, 2007. ISBN 978-0-09-952055-9. First published in the USA by Alfred Knopf, 1974. Page 125.

- ^ T.R. Fehrenbach. Comanches, the history of a people. Vintage Books. London, 2007. ISBN 978-0-09-952055-9. First published in the USA by Alfred Knopf, 1974. Page 553.

- ^ "Amazonian archers". BBC News. 30 May 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ a b Johnes, Martin. "Archery—Romance-and-Elite-Culture-in-England-and-Wales—c-1780-1840 Martin Johnes. Archery, Romance and Elite Culture in England and Wales, c. 1780–1840". Swansea.academia.edu. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "The Royal Company of Archers". Archived from the original on 25 November 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Allely, Steve; et al. (2008), The Traditional Bowyer's Bible, Volume 4, The Lyons Press, ISBN 978-0-9645741-6-8

- ^ Kroeber, Theodora (2004), Ishi in Two Worlds: a biography of the last wild Indian in North America, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-24037-7

- ^ Pope, Saxton (1925), Hunting with the Bow and Arrow, New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons

- ^ Pope, Saxton (1926), Adventurous Bowmen: field notes on African archery, New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons

- ^ Cherokee Bows and Arrows: How to Make and Shoot Primitive Bows and Arrows. Al Herrin. White Bear Pub (Nov 1989). ISBN 978-0962360138

- ^ Article about the 2009 Chinese Traditional Archery Seminar

- ^ News coverage of the 2010 Chinese Traditional Archery Seminar

- ^ "Magyar index".

- ^ "Bhutanese Traditional Archery".

- ^ Hickman, C. N.; Nagler, Forrest; Klopsteg, Paul E. (1947), Archery: The Technical Side. A compilation of scientific and technical articles on theory, construction, use and performance of bows and arrows, reprinted from journals of science and of archery, National Field Archery Association

- ^ Bertalan, Dan. Traditional Bowyers Encyclopedia: The Bowhunting and Bowmaking World of the Nation's Top Crafters of Longbows and Recurves, 2007. p. 73.

Further reading

- The Traditional Bowyers Bible Volume 1. The Lyons Press, 1992. ISBN 1-58574-085-3

- The Traditional Bowyers Bible Volume 2. The Lyons Press, 1992. ISBN 1-58574-086-1

- The Traditional Bowyers Bible Volume 3. The Lyons Press, 1994. ISBN 1-58574-087-X

- The Traditional Bowyers Bible Volume 4. The Lyons Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-9645741-6-8

External links

- Archery Library Online Archery Books with historical content

- ^ Crombie, Laura (2016). Archery and Crossbow Guilds in Medieval Flanders. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer.