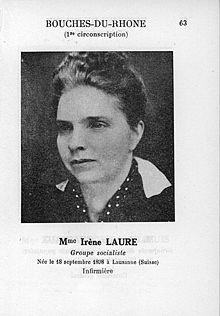

Irène Laure

Irène Laure (born Irène Guelpa, 18 September 1898 – 4 July 1987) was a French socialist activist and politician, a member of the French Resistance and an MP in the 1945 parliament. She became known from 1947 onwards as she led a campaign of several months duration through Germany to ask for forgiveness and to foster French-German reconciliation.

Life[edit]

Irène Guelpa was born in Lausanne, Switzerland, on 18 September 1898 to a public works contractor's family. Her family was Protestant. Irène's political and social conscience was awakened by her observation of the hard life of her father's workers. She later chose to become a nurse.

Political career[edit]

Guelpa was 16 when she joined the Socialist Party (SFIO). On 21 October 1945 - the first election ever open to women in France - she was elected on Gaston Defferre's ticket as an MP to the French National Assembly. She was not re-elected in the following election; the Socialist Party's vote had been seriously eroded by the progress of the Gaullists (MRP) but she became for many years the national secretary of the French Socialist Women organisation.

Resistance[edit]

In spite of the risks, Laure worked for the Resistance. Under German occupation, her children's health suffered, especially for lack of appropriate food. In May 1944, she led a "hunger march" in Marseille. In order to avoid arrest and deportation of the men, she made the march a women-only event. Her particular part of the march walked 17 km from Aubagne to the préfecture in Marseille, 4,000 women demanding larger bread and food allowances. Laure negotiated directly with the Préfet who tried - in vain - to silence her by threatening her. She came through the occupation years without being arrested but her son, Louis, was arrested and was said to have been tortured during his detention.

Caux[edit]

In 1947, she accepted an invitation of representatives of Initiatives of Change (then-named Moral Rearmament), to join the international conferences in Caux, a conference centre opened the year before. Like the creators of Caux, she was keen to participate in the reconstruction of Europe, but upon her arrival the announcement of a massive delegation of Germans made her decide to leave at once. Her memory of her family's suffering under German occupation was too strong for her to talk to Germans. Challenged at the last minute by Frank Buchman, the chief inspirator of Caux, about her true vision for Europe and whether Europe could be rebuilt without the Germans, she reluctantly stayed in Caux. She finally accepted one meeting with one German lady and that meeting turned her around. After Laure spent most of the meeting discharging all of her resentment on her interlocutor, the German lady finally introduced herself: she was Clarita von Trott, the widow of Adam von Trott, a lawyer from Berlin, member of the German Resistance, arrested and executed after the failed attempt on Hitler's life on 20 July 1944. She was imprisoned and her two daughters placed in a SS-run orphanage. She concluded along these lines, "I realise that we didn't resist strong enough, nor soon enough. Because of us you have suffered a great deal. Forgive us please." Remembering this moment, Laure used to say, "On that day I felt free, free as never before."[1] On the same day, she asked to speak in front of the main meeting. 500 people were there including 100 Germans. After briefly telling of her Resistance background, she explained that although nothing could be forgotten, she could decide to forgive and, to the utter amazement of the audience, she concluded by asking the Germans to forgive her for her hate. The Germans present remained speechless until a German lady asked for the word to respond positively. The former Hitlerjugend and Wehrmacht veteran (who became a CDU MP) Peter Petersen remembered this meeting vividly. "I was shaken. For several nights in a row I was unable to sleep. All my past was revolted against this woman's courage. ... One day, we told her how deeply sorry we were and our shame for what our people had done to her and others. We promised her to dedicate our lives to work and prevent such tragedies wherever in the world."[2]

Touring Germany[edit]

From February 1949, Laure visited Germany in order to propagate her forgiveness and reconciliation message. In three months she repeated her excuses almost 200 times in front of regional parliaments, in political and other meetings, on the radio, etc. Each of these declarations remained as costly as the first, but they reached tens of thousands of Germans. In the years that followed, hundreds of German politicians met with their French counterparts in Caux, which created a stepping stone for a wider reconciliation movement. The German chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, declared in 1958 that Laure and her husband Victor were "the couple which did the most over the last 15 years to build unity between the two countries which had been enemies for centuries".[3]

Family life[edit]

Guelpa married Victor Laure, a seaman, in 1920, "with as honeymoon the Tours congress", to which they were both delegates. They were almost separated by the congress, Victor being close to Marcel Cachin and at first in favour of the communist majority. But he finally joined SFIO which had been her choice from the onset.[4] They had five children.

Irène Laure died on 4 July 1987 in La Ciotat.

References[edit]

- ^ "Presentation by Michel Koechlin on 3 March 2001" (in French). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ Catherine Guisan, Un sens à l’Europe : gagner la paix (1950-2003), Publisher Odile Jacob, 2003, Paris, 292 pages, p. 56, ISBN 2738113567

- ^ Michael Henderson, All Her Paths are Peace: Women Pioneers in Peacemaking, Kumarian Press, 1994, total pages: 179, p. 23, ISBN 1565490347

- ^ Jacqueline Piguet, Pour l’amour de demain, Irène Laure racontée, Editions de Caux, 1985, p. 40

Sources[edit]

- Archives of Assemblée nationale (French Parliament)

- Initiatives of Change website

- Gabriel Marcel, Un changement d'espérance, Plon, 1959 (autobiographic text of Irène Laure)

- Exposé de Michel Koechlin le 3 mars 2001

- Antoine Jaulmes, "Plus décisif que la violence", la revue Changer, n°329 thème "Gandhi est-il dépassé?" (January/February 2008)

- "The story of Irene Laure", speech by Michael Henderson

- Jacqueline Piguet, Pour l’amour de demain, Irène Laure racontée Editions de Caux, 1985

- For The Love of Tomorrow, film by Alan Channer