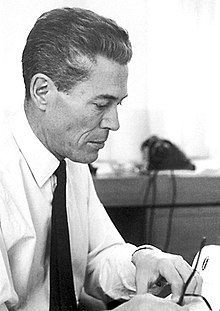

Jacques Monod

Jacques Monod | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Jacques Lucien Monod February 9, 1910 Paris, France |

| Died | May 31, 1976 (aged 66) Cannes, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

Jacques Lucien Monod (February 9, 1910 – May 31, 1976), a French biochemist, won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1965, sharing it with François Jacob and Andre Lwoff "for their discoveries concerning genetic control of enzyme and virus synthesis".[2][3][4][5][6][7]

Monod (along with François Jacob) became famous for his work on the E. coli lac operon, which encodes proteins necessary for the transport and breakdown of the sugar lactose (lac). From their own work and the work of others, he and Jacob came up with a model for how the levels of some proteins in a cell are controlled. In their model, the manufacture of proteins, such as the ones encoded within the lac (lactose) operon, is prevented when a repressor, encoded by a regulatory gene, binds to its operator, a specific site on the DNA next to the genes encoding the proteins. (It is now known that repressor bound to the operator physically blocks RNA polymerase from binding to the promoter, the site where transcription of the adjacent genes begins.)

Study of the control of expression of genes in the lac operon provided the first example of a transcriptional regulation system. Monod also suggested the existence of mRNA molecules that link the information encoded in DNA and proteins. He is widely regarded as one of the founders of molecular biology.[8][9] Monod's interest in the lac operon originated from his doctoral dissertation, for which he studied the growth of bacteria in culture media containing two sugars.[10][11][12][13]

Career and research

In Monod's studies he discovered that the course work was decades behind the current biological science. He learned from other students a little older than himself, rather than from the faculty. "To George Teissier he owes a preference for quantitative descriptions; André Lwoff initiated him into the potentials of microbiology; to Boris Ephrussi he owes the discovery of physiological genetics, and to Louis Rapkine the concept that only chemical and molecular descriptions could provide a complete interpretation of the function of living organisms."[14]

Before his doctoral work, Monod spent a year in the laboratory of Thomas Hunt Morgan at the California Institute of Technology working on Drosophila genetics. This was a true revelation for him and probably influenced him on developing a genetic conception of biochemistry and metabolism.[15]

His doctoral work explored the growth of bacteria on mixtures of sugars and documented the sequential utilization of two or more sugars. He coined the term diauxie to denote the frequent observations of two distinct growth phases of bacteria grown on two sugars. He theorized on the growth of bacterial cultures and promoted the chemostat theory as a powerful continuous culture system to investigate bacterial physiology.[16]

The experimental system ultimately used by Jacob and Monod was a common bacterium, E. coli, but the basic regulatory concept (described in the Lac operon article) that was discovered by Jacob and Monod is fundamental to cellular regulation for all organisms. The key idea is that E. coli does not bother to waste energy making such enzymes if there is no need to metabolize lactose, such as when other sugars like glucose are available. The type of regulation is called negative gene regulation, as the operon is inactivated by a protein complex that is removed in the presence of lactose (regulatory induction).

Monod also made important contributions to the field of enzymology with his proposed theory of allostery in 1965 with Jeffries Wyman (1901-1995) and Jean-Pierre Changeux.[17]

He was also a proponent of the view that life on earth arose by freak chemical accident and was unlikely to be duplicated even in the vast universe. His very striking suggestion was that this accident may not have been simply of low probability but of identically zero probability, a unique event that will never be repeated.[18] "Man at last knows he is alone in the unfeeling immensity of the universe, out of which he has emerged only by chance. His destiny is nowhere spelled out, nor is his duty. The kingdom above or the darkness below; it is for him to choose", he wrote in 1971.[19] He used the bleak assessment that forms the earlier part of the quote as a springboard to argue for atheism and the absurdity and pointlessness of existence. Monod stated we are merely chemical extras in a majestic but impersonal cosmic drama—an irrelevant, unintended sideshow. His views were in direct opposition to the religious certainties of his ancestor Henri's[20] well-known brothers Frédéric Monod and Adolphe Monod. In 1973 he was one of the signers of the Humanist Manifesto II.[21]

Sociologist Howard L. Kaye has suggested that Monod failed in his attempt to banish "mind and purpose from the phenomenon of life" in the name of science.[22]

Monod was not only a biologist but also a fine musician and esteemed writer on the philosophy of science. He was a political activist and chief of staff of operations for the Forces Françaises de l'Interieur during World War II. In preparation for the Allied landings, he arranged parachute drops of weapons, railroad bombings, and mail interceptions.

Awards and honours

In addition to winning the Nobel Prize, Monod was also the Légion d'honneur and elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1968[1]

Personal life

Monod was born in Paris to an American mother from Milwaukee, Charlotte (Sharlie) MacGregor Todd, and a French Huguenot father, Lucien Monod who was a painter and inspired him artistically and intellectually.[1][14] He attended the lycée at Cannes until he was 18.[1] In October 1928 he started his studies in biology at the Sorbonne.[1] During World War II, Monod was active in the French Resistance, eventually becoming the chief of staff of the French Forces of the Interior.[23] He was an Chevalier in the Légion d'Honneur (1945), and was awarded the Croix de Guerre (1945) and the American Bronze Star Medal.[24][25]

In 1938 he married Odette Bruhl (d.1972).[26]

Jacques Monod died of leukemia in 1976 and was buried in the Cimetière du Grand Jas in Cannes on the French Riviera.

Quotations

- "The first scientific postulate is the objectivity of nature: nature does not have any intention or goal."[4]

- "Anything found to be true of E. coli must also be true of elephants."[27]

- "The universe is not pregnant with life nor the biosphere with man...Man at last knows that he is alone in the unfeeling immensity of the universe, out of which he emerged only by chance. His destiny is nowhere spelled out, nor is his duty. The kingdom above or the darkness below; it is for him to choose"[28]

References

- ^ a b c d e Lwoff, A. M. (1977). "Jacques Lucien Monod. 9 February 1910 -- 31 May 1976". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 23: 384–412. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1977.0015.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1965 François Jacob, André Lwoff, Jacques Monod". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ The Statue Within: an autobiography by François Jacob, Basic Books, 1988. ISBN 0-465-08223-8 Translated from the French. 1995 paperback: ISBN 0-87969-476-9

- ^ a b Chance and Necessity: An Essay on the Natural Philosophy of Modern Biology by Jacques Monod, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1971, ISBN 0-394-46615-2

- ^ Of Microbes and Life, Jacques Monod, Ernest Bornek, June 1971, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-03431-8

- ^ The Eighth Day of Creation: makers of the revolution in biology by Horace Freeland Judson, Simon and Schuster, 1979. ISBN 0-671-22540-5. Expanded Edition Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory Press, 1996. ISBN 0-87969-478-5. Widely[quantify]-praised[by whom?] history of molecular biology recounted through the lives and work of the major figures, including Monod.

- ^ Origins of Molecular Biology: a Tribute to Jacques Monod edited by Agnes Ullmann, Washington, ASM Press, 2003, ISBN 1-55581-281-3. Jacques Monod seen by persons who interacted with him as a scientist.

- ^ Ullmann, Agnès (2003). Origins of molecular biology: a tribute to Jacques Monod. ASM Press. p. xiv. ISBN 1-55581-281-3.

- ^ Stanier, R. (1977). "Jacques Monod, 1910–1976". Journal of general microbiology. 101 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1099/00221287-101-1-1. PMID 330816.

- ^ From enzymatic adaptation to allosteric transitions, Jacques Monod, Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1965

- ^ Biography of Jacques Monod at Nobel e-Museum

- ^ Video interview with Jacques Monod Vega Science Trust

- ^ From enzymatic adaptation to allosteric transitions Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1965

- ^ a b "Jacques Monod – Biography". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved June 30, 2010.

- ^ Peluffo, Alexandre E. (July 1, 2015). "The "Genetic Program": Behind the Genesis of an Influential Metaphor". Genetics. 200 (3): 685–696. doi:10.1534/genetics.115.178418. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 4512536. PMID 26170444.

- ^ 1949, Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 3:371–394; 1950, Ann. Inst. Pasteur., 79:390–410

- ^ Monod, J.; Wyman, J.; Changeux, J. P. (1965). "On the Nature of Allosteric Transitions: A Plausible Model". Journal of Molecular Biology. 12: 88–118. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(65)80285-6. PMID 14343300.

- ^ Monad, Jacques (1971). Chance and Necessity. p. xii.

- ^ Monod, Jacques (1971). Chance and Necessity. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 180. ISBN 0-394-46615-2.

- ^ fr:Descendance de Jean Monod (1765-1836)

- ^ "Humanist Manifesto II". American Humanist Association. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kaye, Howard L. The Social Meaning of Modern Biology (1997) Transaction Publishers p. 75

- ^ Caroll, Sean (2013). Brave Genius: A Scientist, a Philosopher, and Their Daring Adventures from the French Resistance to the Nobel Prize. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0307952332.

- ^ Prial, Frank (June 1, 1976). "Jacques Monod, Nobel Biologist, Dies; Thought Existence Is Based on Chance". The New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- ^ "Jacques Monod – Biographical". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0 902 198 84 X.

- ^ Friedmann, Herbert Claus (2004). "From 'Butyribacterium' to 'E. coli' : An Essay on Unity". Biochemistry Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 47 (1): 47–66. doi:10.1353/pbm.2004.0007.

- ^ Davies, Paul (2010). The Eerie Silence. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-547-13324-9.

Further reading

- Sean B. Carroll (2014). Brave Genius: A Scientist, a Philosopher, and Their Daring Adventures from the French Resistance to the Nobel Prize. Broadway Books. ISBN 978-0307952349.

- Collège de France faculty

- French microbiologists

- French geneticists

- French biochemists

- Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine

- French Nobel laureates

- French atheists

- French humanists

- French Resistance members

- 1910 births

- Foreign Members of the Royal Society

- 1976 deaths

- Scientists from Paris

- Burials at the Cimetière du Grand Jas

- Pasteur Institute

- Légion d'honneur recipients