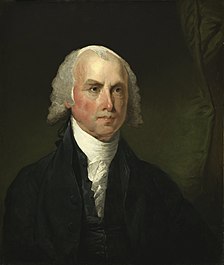

James Madison

James Madison | |

|---|---|

James Madison by John Vanderlyn, 1816 | |

| 4th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1809 – March 4, 1817 | |

| Vice President | George Clinton (1809–1812) None (1812–1813) Elbridge Gerry (1813–1814) None (1814–1817) |

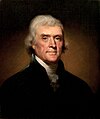

| Preceded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| Succeeded by | James Monroe |

| 5th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office May 2, 1801 – March 3, 1809 | |

| President | Thomas Jefferson |

| Preceded by | John Marshall |

| Succeeded by | Robert Smith |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia's 15th district | |

| In office March 4, 1793 – March 4, 1797 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | John Dawson |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia's 5th district | |

| In office March 4, 1789 – March 4, 1793 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | George Hancock |

| Delegate to the Congress of the Confederation from Virginia | |

| In office March 1, 1781 – November 1, 1783 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 16, 1751 Port Conway, Colony of Virginia, British America |

| Died | June 28, 1836 (aged 85) Orange, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Montpelier, Orange, Virginia |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican (founder 1791) |

| Height | 5 ft 4 in (163 cm) [1] |

| Spouse | |

| Children | John (stepson) |

| Alma mater | Princeton University |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Colony of Virginia |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1775 |

| Rank | |

James Madison Jr., (March 16 [O.S. March 5], 1751 – June 28, 1836) was an American statesman and Founding Father who served as the fourth President of the United States from 1809 to 1817. He is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for his pivotal role in drafting and promoting the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Madison inherited his plantation Montpelier in Virginia and therewith owned hundreds of slaves during his lifetime. He served as both a member of the Virginia House of Delegates and as a member of the Continental Congress prior to the Constitutional Convention. After the Convention, he became one of the leaders in the movement to ratify the Constitution, both in Virginia and nationally. His collaboration with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay produced The Federalist Papers, among the most important treatises in support of the Constitution. Madison's political views changed throughout his life. During deliberations on the Constitution, he favored a strong national government, but later preferred stronger state governments, before settling between the two extremes later in his life.

In 1789, Madison became a leader in the new House of Representatives, drafting many general laws. He is noted for drafting the first ten amendments to the Constitution, and thus is known also as the "Father of the Bill of Rights." He worked closely with President George Washington to organize the new federal government. Breaking with Hamilton and the Federalist Party in 1791, he and Thomas Jefferson organized the Democratic-Republican Party. In response to the Alien and Sedition Acts, Jefferson and Madison drafted the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, arguing that states can nullify unconstitutional laws.

As Jefferson's Secretary of State (1801–1809), Madison supervised the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the nation's size. Madison succeeded Jefferson as president in 1809, was re-elected in 1813, and presided over renewed prosperity for several years. After the failure of diplomatic protests and a trade embargo against the United Kingdom, he led the U.S. into the War of 1812. The war was an administrative morass, as the United States had neither a strong army nor financial system. As a result, Madison afterward supported a stronger national government and military, as well as the national bank, which he had long opposed. Madison has been ranked in the aggregate by historians as the ninth most successful president.

Early life and education

James Madison, Jr., was born on March 16, 1751, (March 5, 1751, Old Style, Julian calendar) at Belle Grove Plantation near Port Conway, Virginia, to father James Madison, Sr., and mother Nelly Conway Madison. He grew up as the oldest of twelve children,[2] with seven brothers and four sisters. Three of James Jr.'s brothers died as infants, including one who was stillborn. In the summer of 1775, his sister Elizabeth (age 7) and his brother Reuben (age 3) died from a dysentery epidemic that swept through Orange County because of contaminated water.[3] His father, James Madison, Sr. (1723–1801), was a tobacco planter who grew up on a plantation, then called Mount Pleasant, which he had inherited upon reaching adulthood. He later acquired more property and slaves, and with 5,000 acres (2,000 ha), he became the largest landowner and a leading citizen in the Piedmont. James Jr.'s mother, Nelly Conway Madison (1731–1829), was born at Port Conway, the daughter of a prominent planter and tobacco merchant.[4] In these years, the southern colonies were becoming a slave society, in which slave labor powered the economy and slaveholders formed the political elite.[5]

From age 11 to 16, young "Jemmy" Madison was sent to study under Donald Robertson, an instructor at the Innes Plantation in King and Queen County, Virginia, in the Tidewater region. Robertson was a Scottish teacher who tutored a number of prominent plantation families in the South. From Robertson, Madison learned mathematics, geography, and modern and classical languages—he became especially proficient in Latin. He attributed his instinct for learning "largely to that man [Robertson]."[6][7]

At age 16, he returned to Montpelier, where he began a two-year course of study under the Reverend Thomas Martin in preparation for college. Unlike most college-bound Virginians of his day, Madison did not attend the College of William and Mary, where the lowland Williamsburg climate—more susceptible to infectious disease—might have strained his delicate health. Instead, in 1769, he enrolled at the College of New Jersey, now Princeton University, where he became roommates and close friends with poet Philip Freneau. Madison proposed in vain to Freneau's sister Mary.[8]

Through diligence and long hours of study that may have compromised his health,[9] Madison graduated in 1771. His studies included Latin, Greek, science, geography, mathematics, rhetoric, and philosophy. Great emphasis was placed on speech and debate also; Madison helped found the American Whig Society, in direct competition to fellow student Aaron Burr's Cliosophic Society. After graduation, Madison remained at Princeton to study Hebrew, in which he became quite fluent, and political philosophy under the university president, John Witherspoon, before returning to Montpelier in the spring of 1772. Madison studied law from his interest in public policy rather than the intent to practice law.[10]

Religion

Although educated by Presbyterian clergymen, young Madison was an avid reader of English deist tracts.[11] As an adult, Madison paid little attention to religious matters. Though most historians have found little indication of his religious leanings after he left college,[12] some scholars indicate he leaned toward deism.[13][14] Others maintain that Madison accepted Christian tenets and formed his outlook on life with a Christian world view.[15]

Military service and early political career

After graduation from Princeton, Madison became interested in the relationship between the American colonies and Great Britain, which deteriorated over the issue of British taxation. In 1774, Madison took a seat on the local Committee of Safety, a patriot pro-revolution group that oversaw the local militia. This was the first step in a life of public service that his family's wealth facilitated.[16] In October 1775, at the start of the American Revolutionary War, he was commissioned as the colonel of the Orange County militia, serving as his father's second-in-command until his election as a delegate to the Fifth Virginia Convention, which produced Virginia's first constitution.[17]

At the Virginia constitutional convention, Madison supported the Virginia Declaration of Rights, though he argued that it should contain stronger protections for freedom of religion.[18] He had earlier witnessed the persecution of Baptist preachers in Virginia, who were arrested for preaching without a license from the established Anglican Church. He collaborated with the Baptist preacher Elijah Craig to promote constitutional guarantees for religious liberty in Virginia.[19] Madison and Thomas Jefferson, who became a mentor to Madison, drafted the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which was finally passed in 1786.[20]

Madison served on the Virginia governor's Council of State from 1777 to 1779, at which point he was elected to the Congress of the Confederation. The country faced a difficult war against Great Britain, as well as runaway inflation, financial troubles, and lack of cooperation between the different levels of government. Madison worked to make himself an expert on financial issues, becoming deeply involved in congressional committees, becoming a legislative workhorse and a master of parliamentary coalition building.[16] Frustrated by the failure of the states to supply needed requisitions, Madison proposed a standing army, a permanent navy, and the ability of Congress to compel states to meet their war-time obligations. Madison also persuaded Virginia to give up its claims to northwestern territories—consisting of most of modern-day Ohio and points west—to the Continental Congress.[citation needed] After serving Congress from 1781 to 1783, Madison won election to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1784.[21]

Madison served in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1784 to 1786. During these years in the House of Delegates, Madison grew increasingly frustrated with what he saw as excessive democracy. He criticized the tendency for delegates to cater to the particular interests of their constituents, even if such interests were destructive to the state at large. In particular, he was troubled by a law that denied diplomatic immunity to ambassadors from other countries, and a law that legalized paper money.[22] He thought legislators should be "disinterested" and act in the interests of their state at large, even if this contradicted the wishes of constituents. Madison believed this "excessive democracy" was the cause of a larger social decay which he and others (such as Washington) thought had resumed after the revolution and was nearing a tipping point—Shays' Rebellion was an example.[22]

Father of the Constitution

of the U.S. Constitution

The Articles of Confederation established the United States as an association of sovereign states with a weak central government. This arrangement was met with disapproval, and was mostly unsuccessful after the war. Congress had no power to tax, and was unable to pay debts from the Revolution, which concerned Madison and other nationalists, such as Washington and Alexander Hamilton, who feared national bankruptcy and disunion.[23] The historian Gordon S. Wood has noted that many leaders, including Madison and Washington, feared more that the revolution had not fixed the social problems that had triggered it and that the excesses ascribed to the King were being seen in the state legislatures. Shays' Rebellion is often cited as the event that forced the issue; Wood argues that many at the time saw it as only the most extreme example of democratic excess.[22]

As Madison wrote, "a crisis had arrived which was to decide whether the American experiment was to be a blessing to the world, or to blast for ever the hopes which the republican cause had inspired."[24] Madison initially hoped to amend the Articles of Confederation, and at the 1786 Annapolis Convention, he supported the calling of another convention to consider amending the Articles. After winning election to another term in the Congress of the Confederation, Madison helped convince the other Congressmen to authorize the Philadelphia convention for the purposes of proposing new amendments. But Madison had come to believe that the ineffectual Articles had to be superseded by a new constitution, and he began preparing for a convention that would do more than merely propose amendments. Madison was pivotal in persuading Washington to attend the 1787 convention—he knew how instrumental the general would be to the adoption of a new constitution.[25]

Years earlier Madison had pored over crates of books that Jefferson sent him from France on various forms of government. The historian Douglas Adair called Madison's work "probably the most fruitful piece of scholarly research ever carried out by an American."[26] As a quorum was being reached for the convention to begin, the 36-year-old Madison wrote what became known as the Virginia Plan, an outline for a new constitution.[27] Many delegates were surprised to learn that the plan called for the abrogation of the Articles and the creation of a new constitution, to be ratified by special conventions in each state rather than the state legislatures. Nonetheless, with the assent of prominent attendees such as Washington and Benjamin Franklin, the delegates went into a secret session to consider the creation of a new constitution.[28] Though the Virginia Plan was an outline rather than a draft of a possible constitution, and though it was extensively changed during the debate (especially by John Rutledge and James Wilson in the Committee of Detail), its use at the convention led many to call Madison the "Father of the Constitution".[29]

During the course of the Convention, Madison spoke over two hundred times, and his fellow delegates rated him highly. William Pierce wrote that "... every Person seems to acknowledge his greatness. In the management of every great question he evidently took the lead in the Convention ... he always comes forward as the best informed Man of any point in debate." Madison recorded the unofficial minutes of the convention, and these have become the only comprehensive record of what occurred. The historian Clinton Rossiter regarded Madison's performance as "a combination of learning, experience, purpose, and imagination that not even Adams or Jefferson could have equaled."[30]

Gordon Wood argues Madison's frustrating experience in the Virginia legislature years earlier most shaped his constitutional views. Wood notes that the governmental structure in both the Virginia Plan and the final constitution were not innovative, since they were copied from the British government, had been used in the states since 1776, and numerous authors had already argued for their adoption at the national level.[31] The controversial elements in the Virginia Plan were removed, and the rest was commonly accepted as necessary for a functional government (state or national) for decades, hence Madison's contribution was considered more qualitative.[31] Wood argues that, like most national politicians of the late 1780s, Madison believed that the problem was less with the Articles of Confederation than with the nature of the state legislatures. He believed the solution was to restrain the excesses of the states. This required more than an alteration in the Articles of Confederation; it required a change in the character of the national compact. The ultimate question before the convention, Wood notes, was not how to design a government but whether the states should remain sovereign, whether sovereignty should be transferred to the national government, or whether the constitution should settle somewhere in between.[31]

Those, like Madison, who thought democracy in the state legislatures was excessive and insufficiently "disinterested", wanted sovereignty transferred to the national government, while those (like Patrick Henry) who did not think this a problem, wanted to fix the Articles of Confederation. Madison was among the few delegates who wanted to deprive the states of sovereignty completely, which he considered the only solution to the problem. Though sharing the same goal as Madison, most other delegates reacted strongly against such an extreme change to the status quo. Though Madison lost most of his battles over how to amend the Virginia Plan (most importantly over the exclusion of the Council of Revision), in the process he increasingly shifted the debate away from a position of pure state sovereignty. Since most disagreements over what to include in the constitution were ultimately disputes over the balance of sovereignty between the states and national government, Madison's influence was critical. Wood notes that Madison's ultimate contribution was not in designing any particular constitutional framework, but in shifting the debate toward a compromise of "shared sovereignty" between the national and state governments.[31][32]

The Federalist Papers and ratification debates

Following the Constitutional Convention, there ensued an intense battle over the Constitution's ratification. Each state was requested to hold a special convention to deliberate and determine whether or not to ratify the Constitution.[33] Madison returned to New York, where the Confederation Congress was in session.[34] There he was approached by Alexander Hamilton, who asked him to help write The Federalist Papers, a series of 85 newspaper articles published in New York that explained and defended the proposed Constitution. Under the pseudonym Publius, Hamilton, Madison, and John Jay wrote 85 essays in the span of six months, with Madison writing 29 of the essays. The articles were also published in book form and became a virtual debater's handbook for the supporters of the Constitution in the ratifying conventions. Historian Clinton Rossiter called The Federalist Papers "the most important work in political science that ever has been written, or is likely ever to be written, in the United States."[35] Federalist No. 10, Madison's first contribution the papers, became highly regarded in the 20th century for its advocacy for representative democracy.[36]

Consensus held that if Virginia, the most populous state at the time, did not ratify the Constitution, the new national government would not likely succeed. When the Virginia Ratifying Convention began on June 2, 1788, the Constitution had not yet been ratified by the required nine states. New York, the second largest state and a bastion of anti-federalism, would likely not ratify it without Virginia, and Virginia's exclusion from the new government would disqualify Virginian George Washington from being the first president.[37] Virginia delegates believed that Washington's election as the first president was a condition for their acceptance of the new constitution and the new government. Arguably the most prominent anti-federalist, the powerful orator Patrick Henry was a delegate and had a following second only to Washington (who was not a delegate). Most delegates believed that Virginians mainly opposed the constitution.[37] Initially Madison did not want to stand for election to the Virginia ratifying convention, but was persuaded to do so because the situation looked so bad. His role at the convention was likely critical to Virginia's ratification, and thus to the success of the constitution generally.[37]

Although Henry was by far the more powerful and dramatic speaker, Madison successfully matched him. Madison's expertise on the subject he had long argued for allowed him to respond with rational arguments to Henry's emotional appeals.[38] Madison persuaded prominent figures such as Edmund Randolph, who had refused to endorse the constitution at the convention, to change their position and support it at the ratifying convention. Randolph's switch likely changed the votes of several more anti-federalists.[39] When the vote was nearing, and the constitution appeared headed for defeat, Madison pleaded with a small group of anti-federalists, and promised them that, if they changed their votes, he would later push for a bill of rights to provide limits to the power of the new government.[citation needed]

A resolution was proposed that a declaration of rights be referred to the other States in the American Confederation for their consideration prior to ratification of the constitution.[40] Supported by George Mason and Patrick Henry but opposed by Madison, Henry Lee III (Light-Horse Harry Lee), John Marshall, Randolph, and Bushrod Washington, the resolution failed, 88–80.[40] Lee, Madison, Marshall, Randolph, and Washington then voted in favor of a resolution to ratify the constitution, which the convention approved on June 28, 1789 by a vote of 89–79, with Mason and Henry voting in the minority.[40]

Addressing slavery in the Constitution, Madison set out with a view that African American slaves as an "unfortunate race" and believed their true nature was both human and property.[41] On February 12, 1788, Madison, in the Federalist Letter No. 54, stated that the Constitutional three-fifths compromise clause was the best alternative for the slaves' current condition and for determining representation of citizens in Congress.[41] Madison believed that slaves, as property, would be protected by both their masters and the government.[41]

Madison was called the "Father of the Constitution" by his peers in his lifetime. However, he was modest, and he protested the title as being "a credit to which I have no claim. ... The Constitution was not, like the fabled Goddess of Wisdom, the offspring of a single brain. It ought to be regarded as the work of many heads and many hands".[42] He wrote Hamilton at the New York ratifying convention, stating his opinion that "ratification was in toto and 'for ever'".[43][44]

Member of Congress

After Virginia ratified the constitution, Madison returned to New York to resume his duties in the Congress of the Confederation. At the request of Washington, Madison sought a seat in the United States Senate, but his election was blocked by Patrick Henry. Madison then decided to run for a seat in the United States House of Representatives. At Henry's behest, the Virginia legislature created congressional districts designed to deny Madison a seat, and Henry recruited a strong challenger to Madison in James Monroe. Locked in a difficult race against Monroe, Madison promised to support a series of constitutional amendments to protect individual liberties.[45] Madison's promise paid off, as he won election to Congress with 57% of the vote.[46] He would continue to serve in the House until 1797, when Madison briefly left public office to preside over his plantation.[47] Early in his tenure, Madison became an ally of President Washington, who looked to Madison as the person who best understood the constitution.[48]

Father of the Bill of Rights

Though the idea for a bill of rights had been suggested at the end of the constitutional convention, the delegates wanted to go home and thought the proposal unnecessary. The omission of a bill of rights became the main argument of the anti-federalists against the constitution. Though no state conditioned ratification of the constitution on a bill of rights, several states came close, and the issue almost prevented the constitution from being ratified. Some anti-federalists continued to contest this after the constitution was ratified and threatened the entire nation with another, more partisan, constitutional convention. Madison objected to a specific bill of rights for several reasons:[49] he thought it was unnecessary, since it purported to protect against powers that the federal government had not been granted; he also considered the enumeration of some rights might be taken to imply the absence of other rights; and that at the state level, bills of rights had proven to be useless paper barriers against government powers.[50]

Though few in the new congress wanted to debate a possible Bill of Rights (for the next century, most thought that the Declaration of Independence, not the first ten constitutional amendments, constituted the true Bill of Rights), Madison pressed the issue.[51] Congress was busy setting up the new government, most wanted to wait for the system to show its defects before amending the constitution, and the anti-federalist movements (which had demanded a new convention) had died out quickly once the constitution was ratified. Despite this, Madison still feared that the states would compel congress to call for a new constitutional convention, which they had the right to do. He also believed that the constitution did not sufficiently protect the national government from excessive democracy and parochialism (the defects he saw in the state governments), so he saw the amendments as mitigation of these problems. On June 8, 1789, Madison introduced his bill proposing amendments consisting of Nine Articles comprising up to 20 potential amendments. Madison initially proposed that the amendments be incorporated into the body of the Constitution. The House passed most of the amendments, but rejected the idea of placing them in the body of the Constitution. Instead, it adopted 17 amendments to be attached separately and sent this bill to the Senate.[52][53]

Madison was a staunch proponent of the right of Americans to a civil jury trial. He initially introduced an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that guaranteed all citizens the right to a jury trial in all civil cases where there was $20 or more at stake. While the original amendment failed, the guaranty of a civil jury trial was incorporated into the Bill of Rights as the Seventh Amendment to the United States Constitution.[54] In June 1789, urging adoption of the right to civil jury trials, he explained, "Trial by jury in civil cases is as essential to secure the liberty of the people as any one of the pre-existent rights of nature."[55]

The Senate edited the amendments still further, making 26 changes of its own, and condensing their number to twelve.[56] Madison's proposal to apply parts of the Bill of Rights to the states as well as the federal government was eliminated, as was his final proposed change to the preamble.[57] A House–Senate Conference Committee then convened to resolve the numerous differences between the two Bill of Rights proposals. On September 24, 1789, the committee issued its report, which finalized 12 Constitutional Amendments for the House and Senate to consider. This version was approved by joint resolution of Congress on September 25, 1789.[58][59]

Articles Three through Twelve were ratified as additions to the Constitution December 15, 1791, and became the Bill of Rights.[60] Article Two became part of the Constitution in 1992 as the Twenty-seventh Amendment. Article One is technically still pending before the states.[61]

Debates on foreign policy

When Britain and France went to war in 1793, the U.S. was caught in the middle. The 1778 treaty of alliance with France was still in effect, yet most of the new country's trade was with Britain. War with Britain became imminent in 1794, after the British seized hundreds of American ships that were trading with French colonies. Madison believed that the United States was stronger than Britain, and that a trade war with Britain, although risking a real war by that government, would probably succeed, and allow Americans to assert their independence fully. Great Britain, he charged, "has bound us in commercial manacles, and very nearly defeated the object of our independence." According to Varg, Madison discounted the more powerful British military when the latter declared "her interests can be wounded almost mortally, while ours are invulnerable." The British West Indies, Madison maintained, could not live without American foodstuffs, but Americans could easily do without British manufactures. He concluded, "it is in our power, in a very short time, to supply all the tonnage necessary for our own commerce".[62] Washington avoided a trade war and instead secured friendly trade relations with Britain through the Jay Treaty of 1794. Madison's harsh and unsuccessful opposition to the treaty led to a permanent break with Washington, ending a long friendship. The debate over the Jay Treaty would serve as the catalyst for the creation of the country's first political parties.[63]

Founding the Democratic-Republican party

Supporters for ratification of the Constitution became known as the Federalist Party. Those in opposition were labeled Anti-Federalists, but neither group was a political party in the modern sense. Following ratification and formation of the first government in 1789, two new political factions formed along similar lines as the old division. The supporters of Alexander Hamilton's attempts to strengthen the national government called themselves Federalists, while those who opposed Hamilton called themselves "Republicans" (later historians would refer to them as the Democratic-Republican Party). Madison and other Republican Party organizers, who favored states' rights and local control, were struggling to find an institutional solution to the Constitution's seeming inability to prevent concentration of power in an administrative republic.[64] As first Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton created many new federal institutions, including the Bank of the United States. Madison led the unsuccessful attempt in Congress to block Hamilton's proposal, arguing that the new Constitution did not explicitly allow the federal government to form a bank. As early as May 26, 1792, Hamilton complained, "Mr. Madison cooperating with Mr. Jefferson is at the head of a faction decidedly hostile to me and my administration."[65] As Hamilton's influence in the administration grew, Madison and Jefferson increasingly came to fear the possible restoration of a monarchy, and they worked together to build an opposition to Hamilton's policies. By the end of Washington's term, most Congressmen identified as either Democratic-Republicans or Federalists.[66]

Washington and Hamilton both left the government after 1797, but Madison and Jefferson remained in opposition during the Federalist presidency of John Adams.[67] In 1798, the U.S. and France unofficially became combatants in the Quasi War, that involved naval warships and commercial vessels battling in the Caribbean. The Federalists created a standing army and passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, which were directed at French refugees engaged in American politics and against Republican editors. In response, Madison and Jefferson secretly drafted the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions declaring the enactments to be unconstitutional and noted that "states, in contesting obnoxious laws, should 'interpose for arresting the progress of the evil.'"[68] The resolutions were largely unpopular, even among republicans, since they called for state governments to invalidate federal laws. Jefferson went further, urging states to secede if necessary, though Madison convinced Jefferson to relent this extreme view.[68]

According to Chernow, Madison's position "was a breathtaking evolution for a man who had pleaded at the Constitutional Convention that the federal government should possess a veto over state laws." Chernow argues that Madison's politics remained closely aligned with Jefferson's until his experience as president with a weak national government during the War of 1812 caused Madison to appreciate the need for a strong central government to aid national defense. At the time, he began to support a national bank, a stronger navy, and a standing army.[68]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The historian Gordon S. Wood says that Lance Banning, as in his Sacred Fire of Liberty (1995), is the "only present-day scholar to maintain that Madison did not change his views in the 1790s."[69] In claiming this, Banning downplays Madison's nationalism in the 1780s.[69] Wood notes that many historians struggle to understand Madison, but Wood looks at him in the terms of Madison's own times—as a nationalist but one with a different conception of nationalism from that of the Federalists. He wanted to avoid a European-style government and always thought that the embargo would ultimately have been successful.[69] Thus, Wood assesses Madison from a different point of view.[69] Gary Rosen and Banning use other approaches to suggest Madison's consistency.[70][71][72]

Marriage and family

Madison was married for the first time at the age of 43; on September 15, 1794, James Madison married Dolley Payne Todd, a 26-year-old widow, at Harewood, in what is now Jefferson County, West Virginia.[73] Madison had no children but adopted Todd's one surviving son, John Payne Todd (known as Payne), after the marriage.

Dolley Payne was born May 20, 1768, at the New Garden Quaker settlement in North Carolina, where her parents, John Payne and Mary Coles Payne, lived briefly. Dolley's sister, Lucy Payne, had recently married George Steptoe Washington, a nephew of President Washington. As a member of Congress, Madison had doubtless met the widow Todd at social functions in Philadelphia, then the nation's capital. She had been living there with her late husband. In May 1794, Madison asked their mutual friend Aaron Burr to arrange a meeting. By August, she had accepted his proposal of marriage. For marrying Madison, a non-Quaker, she was expelled from the Society of Friends. Also in 1794 Madison was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[74]

Dolley Madison put her social gifts to use when the couple lived in Washington, beginning when he was Secretary of State. With the White House still under construction, she advised as to its furnishings and sometimes served as First Lady for ceremonial functions for President Thomas Jefferson, a widower and friend. When her husband was president, she created the role of First Lady, using her social talents to advance his program. She is credited with adding to his popularity in office.[citation needed]

Madison's father died in 1801 and at age 50, Madison inherited the large plantation of Montpelier and other holdings, and his father's 108 slaves. He had begun to act as a steward of his father's properties by 1780.[75]

United States Secretary of State 1801–1809

Jefferson defeated Adams in the 1800 presidential election. Jefferson wanted to oversee his administration's foreign policy, and he selected the loyal Madison for the position of Secretary of State despite the latter's lack of foreign policy experience. Along with Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin, Madison became of the two major influences in Jefferson's cabinet.[76] At the start of his term, Madison was a party to the United States Supreme Court case Marbury v. Madison (1803), in which the doctrine of judicial review was asserted by the high Court, much to the annoyance of the Jeffersonians who did not want a powerful federalist judiciary.[citation needed] Throughout Jefferson's presidency, much of Europe was at war, and the main challenge to the Jefferson administration was maintaining neutrality during the Napoleonic Wars.[77]

Shortly before Jefferson's election, Napoleon seized power from the hapless French Directory, which had recently mismanaged France's finances in unsuccessful wars and had lost control of Saint-Domingue (Haiti) after a slave rebellion. Beginning in 1802, Napoleon sent more than 20,000 troops in an attempt to restore slavery on the island, as its colonial sugar cane plantations had been the chief revenue producer for France in the New World. The warfare went badly and the troops were further decimated by yellow fever. Napoleon gave up on the restoration of a colonial empire in the Americas and offered to sell the Louisiana territory to the United States in 1803. Later that year, the remaining 7,000 French troops were withdrawn from the island, and in 1804 Haiti declared its independence as the second republic in the western hemisphere.[citation needed]

Jefferson had originally sent delegates to France to negotiate the sale of New Orleans, but upon learning of Napoleon's offer to sell the entire Louisiana territory, Jefferson quickly agreed to it, resulting in the Louisiana Purchase. Many contemporaries and later historians, such as Ron Chernow, noted that Madison and President Jefferson ignored their "strict construction" of the Constitution to take advantage of the purchase opportunity. Jefferson would have preferred a constitutional amendment authorizing the purchase, but did not have time nor was he required to do so. The Senate quickly ratified the treaty providing for the purchase. The House, with equal alacrity, passed enabling legislation.[78] The Jefferson administration argued that the purchase had included West Florida, but France refused to acknowledge this and Florida remained under the control of Spain.[79]

With the wars raging in Europe, Madison tried to maintain American neutrality, and insisted on the legal rights of the U.S. as a neutral party under international law. Neither London nor Paris showed much respect, however, and the situation deteriorated during Jefferson's second term. After Napoleon achieved victory at over his enemies in continental Europe at the Battle of Austerlitz, he became more aggressive and tried to starve Britain into submission with an embargo that was economically ruinous to both sides. Madison and Jefferson also decided on an embargo to punish Britain and France, forbidding American trade with any foreign nation. The embargo failed in the United States just as it did in France, and caused massive hardships up and down the seaboard, which depended on foreign trade. The Federalists made a comeback in the Northeast by attacking the embargo, which was allowed to expire just as Jefferson was leaving office.[80]

Election of 1808

With Jefferson's retirement imminent as his second term came to a close, Madison became his party's choice for president in 1808. He was opposed by Rep. John Randolph, who had broken earlier with Jefferson and Madison. The Republican Party Congressional caucus chose the candidate and easily selected Madison over James Monroe.[81] As the Federalist Party by this time had largely collapsed outside New England, Madison easily defeated Federalist Charles Cotesworth Pinckney.[82] At a height of only five feet, four inches (163 cm), and never weighing more than 100 pounds, he became the most diminutive president.[83]

Presidency 1809–1817

Upon his inauguration in 1809, Madison immediately faced opposition to his planned nomination of Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin as Secretary of State, led by Sen. William B. Giles. Madison chose not to fight Congress for the nomination but kept Gallatin, a carry over from the Jefferson administration, in the Treasury Department. The talented Swiss-born Gallatin was Madison's primary advisor, confidant, and policy planner.[84] Madison appointed Robert Smith for Secretary of State, Jefferson's former Secretary of the Navy. For his Secretary of the Navy, Madison appointed Paul Hamilton. Madison's cabinet, which included men of unremarkable talent, was chosen for the purposes of national interest and political harmony. When Madison assumed office in 1809, the federal government had a surplus of $9,500,000; by 1810 the national debt had been reduced, and taxes cut.[85]

Bank of the United States

Madison sought to continue Jefferson's agenda—particularly dismantling the system left behind by the Federalist Party under Washington and Adams. One of the most pressing issues Madison confronted was the first Bank of the United States. Its twenty-year charter was scheduled to expire in 1811, and while Gallatin insisted that the bank was a necessity, Congress failed to re-authorize it. As the absence of a national bank made war with Britain very difficult to finance, Congress passed a bill in 1814 chartering a second national bank. Madison vetoed it.[86] In 1816, Congress passed another bill to charter a second national bank; Madison signed the act.[87][88]

Prelude to war

Congress had repealed the embargo right before Madison became president, but troubles with the British and French continued.[89] America's new "nonintercourse" policy was to trade with all countries including France and Britain if restrictions on shipping were removed.[90] Although initially promising, Madison's diplomatic efforts to get the British to withdraw the Orders in Council were rejected by British Foreign Secretary George Canning in April 1809.[91] Aside from U.S. trade with France, the central dispute between the Great Britain and the United States was the impressment of sailors by the British. During the long and expensive war against France, many British citizens were forced by their own government to join the navy, and many of these conscripts defected to U.S. merchant ships. Unable to tolerate this loss of manpower, the British seized several U.S. ships and forced captured crewmen, some of whom were not in fact not British subjects, to serve in the British navy. This impressment contributed greatly to growing anger towards the British in the United States.[92]

By August 1809, diplomatic relations with Britain deteriorated as minister David Erskine was withdrawn and replaced by "hatchet man" Francis James Jackson.[93] Madison however, resisted calls for war, as he was ideologically opposed to the debt and taxes necessary for a war effort.[94] British historian Paul Langford sees the removal in 1809 of Erskine as a major British blunder:

- The British ambassador in Washington [Erskine] brought affairs almost to an accommodation, and was ultimately disappointed not by American intransigence but by one of the outstanding diplomatic blunders made by a Foreign Secretary. It was Canning who, in his most irresponsible manner and apparently out of sheer dislike of everything American, recalled the ambassador Erskine and wrecked the negotiations, a piece of most gratuitous folly. As a result, the possibility of a new embarrassment for Napoleon turned into the certainty of a much more serious one for his enemy. Though the British cabinet eventually made the necessary concessions on the score of the Orders-in-Council, in response to the pressures of industrial lobbying at home, its action came too late…. The loss of the North American markets could have been a decisive blow. As it was by the time the United States declared war, the Continental System [of Napoleon] was beginning to crack, and the danger correspondingly diminishing. Even so, the war, inconclusive though it proved in a military sense, was an irksome and expensive embarrassment which British statesman could have done much more to avert.[95]

After Jackson accused Madison of duplicity with Erskine, Madison had Jackson barred from the State Department and sent packing to Boston.[96] During his first State of the Union Address in November 1809, Madison asked Congress for advice and alternatives concerning the British-American trade crisis, and warned of the possibility of war. By spring 1810, Madison was specifically asking Congress for more appropriations to increase the Army and Navy in preparation for war with Britain.[97] Together with the effects of European peace, the United States economy began to recover early in Madison's presidency. By the time Madison was standing for reelection, the Peninsular War in Spain had spread, while at the same time Napoleon invaded Russia, and the entire European continent was once again embroiled in war.

By 1809 the Federalist Party was no longer competitive outside a few strongholds. Some former members (such as John Quincy Adams, Madison's ambassador to Russia) had joined Madison's Republican Party.[98] Though one party appeared to dominate, it had begun to split into rival factions, which would later form the basis of the Second Party System. In particular, with hostilities against Britain appearing increasingly likely, factions favoring and opposing a war formed in Congress.[99] The predominant faction, the "War Hawks," were led by House Speaker Henry Clay. When war finally did break out, the war effort was led by the War Hawks in Congress under Clay at least as much as it was by Madison; this accorded with the president's preference for checks and balances.

War of 1812

Powell 1873

With continued attacks by the British on American shipping, both Madison and the broader American public were ready for war with Britain.[100] Many Americans called for a "second war of independence" to restore honor and stature to the new nation.[101] With Britain in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars, many Americans, Madison included, believed that the United States could easily capture Canada, at which point the U.S. could use Canada as a bargaining chip for all other disputes or simply retain control of it.[102] An angry public elected a "war hawk" Congress, led by Clay and John C. Calhoun. On June 1, 1812, Madison asked Congress for a declaration of war.[103] The declaration was passed along sectional and party lines, with intense opposition from the Federalists and the Northeast, where the economy had suffered during Jefferson's trade embargo.[104][105]

Madison hurriedly called on Congress to put the country "into an armor and an attitude demanded by the crisis," specifically recommending enlarging the army, preparing the militia, finishing the military academy, stockpiling munitions, and expanding the navy.[106] Madison faced formidable obstacles—a divided cabinet, a factious party, a recalcitrant Congress, obstructionist governors, and incompetent generals, together with militia who refused to fight outside their states. The most serious problem facing the war effort was lack of unified popular support. There were serious threats of disunion from New England, which engaged in extensive smuggling with Canada and refused to provide financial support or soldiers.[107] Events in Europe also went against the United States. Shortly after the United States declared war, Napoleon launched an invasion of Russia, and the failure of that campaign turned the tide against French and towards Britain and her allies.[108] In the years prior to the war, Jefferson and Madison had reduced the size of the military, closed the Bank of the U.S., and narrowed lowered taxes. These decisions added to the challenges facing the United States, as by the time the war began, Madison's military force consisted mostly of poorly trained militia members.[citation needed]

Military action

Madison hoped that the war would be over in a couple months after the capture of Canada, but his hopes were quickly dashed.[109] Madison had believed the state militias would rally to the flag and invade Canada, but the governors in the Northeast failed to cooperate. Their militias either sat out the war or refused to leave their respective states for action. The senior command at the War Department and in the field proved incompetent or cowardly—the general at Detroit surrendered to a smaller British force without firing a shot. Gallatin discovered the war was almost impossible to fund, since the national bank had been closed and major financiers in the Northeast refused to help.[110] The American campaign in Canada, led by Henry Dearborn, ended with defeat in the Battle of Stoney Creek.[111] The British armed American Indians in the Northwest, most notably several tribes allied with the Shawnee chief, Tecumseh. But, after losing control of Lake Erie at the naval Battle of Lake Erie in 1813, the British were forced to retreat. General William Henry Harrison caught up with them at the Battle of the Thames, where he destroyed the British and Indian armies, killed Tecumseh, and permanently destroyed Indian power in the Great Lakes region. Madison remains the only president to lead troops in battle while in office, although that battle (the Battle of Bladensburg in 1814) did not go well for the American side. The British then raided Washington, as Madison headed a dispirited militia. Dolley Madison rescued White House valuables and documents shortly before the British burned the White House, the Capitol and other public buildings.[112][113]

After the disastrous start to the War of 1812, Madison accepted a Russian invitation to arbitrate the war and sent Gallatin, John Quincy Adams, and James Bayard to Europe in hopes of quickly ending the war.[114] While Madison worked to end the war, the U.S. experienced some military success, particularly at sea. The U.S. naval squadron on Lake Erie successfully defended itself and captured its opponents of the Royal Navy. All six British vessels were captured by the American forces. This victory crippled the supply and reinforcement of British military forces in the western theatre of the war, which forced the British troops and their Native allies to retreat. Commander Oliver Hazard Perry reported his victory with the simple statement, "We have met the enemy, and they are ours."[115] America had built up one of the largest merchant fleets in the world, though it had been partially dismantled under Jefferson and Madison. Madison authorized many of these ships to become privateers in the war. Armed, they captured 1,800 British ships.[116] As part of the war effort, an American naval shipyard was built up at Sackets Harbor, New York, where thousands of men produced twelve warships and had another nearly ready by the end of the war. By 1814, generals Andrew Jackson and William Henry Harrison had destroyed the main Indian threats in the South and West, respectively. In late 1814, Madison and his Secretary of War James Monroe unsuccessfully asked Congress to establish a national draft of 40,000 men.[117]

The courageous, successful defense of Ft. McHenry, which guarded the seaway to Baltimore, against one of the most intense naval bombardments in history (over 24 hours), led Francis Scott Key to write the poem that was set to music as the U.S. national anthem, "The Star Spangled Banner."[118] U.S. victory at the Battle of Plattsburgh ended British hopes of conquering New York.[119] In New Orleans, Gen. Andrew Jackson put together a force including regular Army troops, militia, frontiersmen, Creoles, Native American allies and Jean Lafitte's pirates. The Battle of New Orleans took place two weeks after peace treaty was drafted (but before it was ratified, so the war was not over). The American defenders repulsed the British invasion army in the most decisive victory of the war.[120] The Treaty of Ghent ended the war in February 1815, with no territorial gains on either side. The Americans felt that their national honor had been restored in what has been called "the Second War of American Independence."[121] On March 3, 1815, the U.S. Congress authorized deployment of naval power against Algiers, and two squadrons were assembled and readied for war; the Second Barbary War would mark the beginning of the end for piracy in that region.

To most Americans, the quick succession of events at the end of the war (the burning of the capital, the Battle of New Orleans, and the Treaty of Ghent) appeared as though American valor at New Orleans had forced the British to surrender after almost winning. This view, while inaccurate, strongly contributed to the post-war euphoria that persisted for a decade. It also helps explain the significance of the war, even if it was strategically inconclusive. Napoleon was defeated for the last time at the Battle of Waterloo near the end of Madison's presidency, and as the Napoleonic Wars ended, so did the War of 1812. Madison's final years began an unprecedented period of peace and prosperity, which was called the Era of Good Feelings. Madison's reputation as president improved and Americans finally believed the United States had established itself as a world power.[122]

Postwar economy and internal improvements

With peace established, Americans believed they had an emboldened independence from Britain. The Federalist Party, which had called for secession over the war at the Hartford Convention, dissolved. With Europe finally at peace, the Era of Good Feelings described the prosperity and equable political environment. Some political contention continued; for instance, in 1816, two-thirds of the incumbents in Congress were defeated for re-election after voting to increase their salary. Madison approved a Hamiltonian national bank, an effective taxation system based on tariffs, a standing professional military, and the internal improvements championed by Henry Clay under his American System. In 1816, pensions were extended to orphans and widows from the War of 1812 for a period of 5 years at the rate of half pay.[123]

However, in his last act before leaving office, Madison vetoed the Bonus Bill of 1817, which would have financed more internal improvements of roads, bridges, and canals: "Having considered the bill this day presented to me ... I am constrained by the insuperable difficulty I feel in reconciling this bill with the Constitution of the United States.... The legislative powers vested in Congress are specified and enumerated in ... the Constitution, and it does not appear that the power proposed to be exercised by the bill is among the enumerated powers."[124] Madison rejected the view of Congress that the General Welfare provision of the Taxing and Spending Clause justified the bill: "Such a view of the Constitution would have the effect of giving to Congress a general power of legislation instead of the defined and limited one hitherto understood to belong to them, the terms 'common defense and general welfare' embracing every object and act within the purview of a legislative trust." Madison urged a variety of measures that he felt were "best executed under the national authority," including federal support for roads and canals that would "bind more closely together the various parts of our extended confederacy."[125]

Indian policy

Upon assuming office on March 4, 1809, in his first Inaugural Address to the nation, Madison stated that the federal government's duty was to convert the American Indians by the "participation of the improvements of which the human mind and manners are susceptible in a civilized state".[126] Like Jefferson, Madison had a paternalistic attitude toward American Indians, encouraging the men to give up hunting and become farmers.[127] Although there are scant details, Madison often met with Southeastern and Western Indians who included the Creek and Osage.[127] Madison believed their adoption of European-style agriculture would help the Creek assimilate the values of British-American civilization. As pioneers and settlers moved West into large tracts of Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, and Chickasaw territory, Madison ordered the US Army to protect Native lands from intrusion by settlers, to the chagrin of his military commander Andrew Jackson. Jackson wanted the President to ignore Indian pleas to stop the invasion of their lands[128] and resisted carrying out the president's order.[128] In the Northwest Territory after the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, Indians were pushed off their tribal lands and replaced entirely by white settlers.[128] By 1815, with a population of 400,000 European-American settlers in Ohio, Indian rights to their lands had effectively become null and void.[128]

Later life

by Gilbert Stuart

When Madison left office in 1817 at age 65, he retired to Montpelier, his tobacco plantation in Orange County, Virginia, not far from Jefferson's Monticello. Dolley, who thought they would finally have a chance to travel to Paris, was 49. As with both Washington and Jefferson, Madison left the presidency a poorer man than when elected. His plantation experienced a steady financial collapse, due to the continued price declines in tobacco and also due to his stepson's mismanagement.

Insight into Madison is provided by the first "White House memoir, A Colored Man's Reminiscences of James Madison (1865), authored by his former slave Paul Jennings, who from the age of 10 served the president as a footman, and later as a valet for the rest of Madison's life. After Madison's death, Jennings was purchased in 1845 from Dolley Madison by senator Daniel Webster, who enabled him to work off the cost and gain his freedom. Jennings published his short account in 1865.[129] He had the highest respect for Madison and said he never struck a slave, nor permitted an overseer to do so. Jennings said that if a slave misbehaved, Madison would meet with the person privately to discuss the behavior.[129]

Some historians speculate that Madison's mounting debt was one of the reasons he refused to allow his notes on the Constitutional Convention, or its official records in his possession, to be published in his lifetime. "He knew the value of his notes, and wanted them to bring money to his estate for Dolley's use as his plantation failed—he was hoping for one hundred thousand dollars from the sale of his papers, of which the notes were the gem."[130] Madison's financial troubles weighed on him as deteriorating mental and physical health ensued.

In his later years, Madison became highly concerned about his historic legacy. He resorted to modifying letters and other documents in his possession, changing days and dates, adding and deleting words and sentences, and shifting characters. By the time he had reached his late seventies, this "straightening out" had become almost an obsession. As an example, he edited a letter written to Jefferson criticizing Lafayette—Madison not only inked out original passages, but even forged Jefferson's handwriting as well.[131] Historian Drew R. McCoy has said, "During the final six years of his life, amid a sea of personal [financial] troubles that were threatening to engulf him...At times mental agitation issued in physical collapse. For the better part of a year in 1831 and 1832 he was bedridden, if not silenced... Literally sick with anxiety, he began to despair of his ability to make himself understood by his fellow citizens."[132]

In 1826, after the death of Jefferson, Madison was appointed as the second Rector ("President") of the University of Virginia. He retained the position as college chancellor for ten years until his death in 1836.

c. 1833

In 1829, at the age of 78, Madison was chosen as a representative to the Virginia Constitutional Convention for revision of the commonwealth's constitution. It was his last appearance as a statesman. The issue of greatest importance at this convention was apportionment. The western districts of Virginia complained that they were underrepresented because the state constitution apportioned voting districts by county. The increased population in the Piedmont and western parts of the state were not proportionately represented by delegates in the legislature. Western reformers also wanted to extend suffrage to all white men, in place of the prevailing property ownership requirement. Madison tried in vain to effect a compromise. Eventually, suffrage rights were extended to renters as well as landowners, but the eastern planters refused to adopt citizen population apportionment. They added slaves held as property to the population count, to maintain a permanent majority in both houses of the legislature, arguing that there must be a balance between population and property represented. Madison was disappointed at the failure of Virginians to resolve the issue more equitably.[133]

Madison was also concerned about the continuation of slavery in Virginia and the South. He believed that transportation of free American blacks to Africa offered a solution, as promoted by the American Colonization Society (ACS).[134] He told Lafayette at the time of the convention that colonization would create a "rapid erasure of the blot on our Republican character."[135] The British sociologist Harriet Martineau visited with Madison during her tour of the United States in 1834. She characterized his belief in the colonization solution to slavery as "bizarre and incongruous."[135] Madison may have sold or donated his gristmill in support of the ACS.[134] Historian McCoy believes that "The Convention of 1829... pushed Madison steadily to the brink of self-delusion, if not despair. The dilemma of slavery undid him."[135][136] Like most African Americans of the time, Madison's slaves wanted to remain in the U.S. where they had been born, believed their work earned them citizenship, and resisted "repatriation".[134]

William R. Denslow supposedly found evidence that James Madison might have been a Mason,[137] when in 1795, John Francis Mercer is said to have written to Madison, "I have had no opportunity of congratulating you before on your becoming a free Mason—a very ancient & honorable fraternity."[138] However, in an 1832 letter to Stephen Bates, Madison wrote that he never was a Mason, and was a "stranger to the principles" of it.[139]

Despite failing health, Madison wrote several memoranda on political subjects, including an essay against the appointment of chaplains for Congress and the armed forces. He felt it would produce religious exclusion as well as political disharmony. He was tempted to admit chaplains for the navy, as sailors might otherwise have no opportunity for worship.[140]

Between 1834 and 1835, he sold 25% of his slaves to offset financial losses on his plantation.[134] Madison lived to a year later, increasingly disregarded by the next generation of the American polity.

Madison died of heart failure at Montpelier on June 28. 1836. He was buried in the Madison Family Cemetery at Montpelier,[141] which is maintained to this day.[142]

In 1842, Dolley Madison sold the Montpelier mansion, and in 1844 sold the extensive plantation lands to Henry W. Moncure.[134] She leased half of the remaining slaves to Moncure. The other half were inherited by her, her son John Payne Todd, and James Madison, Jr., a nephew.[134] By 1850, the Montpelier plantation was a "ghost of its former self".[134]

Legacy

The historian Garry Wills wrote, "Madison's claim on our admiration does not rest on a perfect consistency, any more than it rests on his presidency. He has other virtues. ... As a framer and defender of the Constitution he had no peer. ... The finest part of Madison's performance as president was his concern for the preserving of the Constitution. ... No man could do everything for the country—not even Washington. Madison did more than most, and did some things better than any. That was quite enough."[143]

George F. Will wrote that if we truly believed that the pen is mightier than the sword, our nation's capital would have been called "Madison, D.C.", instead of Washington, D.C.[144]

Madison, in The Federalist Papers, in Federalist No. 51, wrote, "It is of great importance in a republic not only to guard the society against the oppression of its rulers, but to guard one part of the society against the injustice of the other part... In a society under the forms of which the stronger faction can readily unite and oppress the weaker, anarchy may as truly be said to reign as in a state of nature, where the weaker individual is not secured against the violence of the stronger."

In 1986, Congress created the James Madison Memorial Fellowship Foundation as part of the bicentennial celebration of the Constitution. The Foundation offers $24,000 graduate level fellowships to secondary teachers to undertake a master's degree which emphasizes the study of the Constitution.

Montpelier, his family's plantation and his home in Orange, Virginia, has been designated a National Historic Landmark.

The James Madison Memorial Building is a building of the United States Library of Congress in Washington, DC and serves as the official memorial to Madison.

Madison is also a character depicted in 2015 musical Hamilton, originated by actor Okieriete Onaodowan both off- and on-Broadway; Madison is portrayed as an ally to Thomas Jefferson and adversary to Alexander Hamilton in the second act of the show.

-

James Madison was honored on a Postage Issue of 1894

-

James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Va., established in 1908

-

Presidential Dollar of James Madison

-

"Madison Cottage" on the site of the Fifth Avenue Hotel at Madison Square, New York City, 1852

-

Auction of books of James Madison's library, Orange County, Virginia, 1854

See also

- Republicanism

- Report of 1800, produced by Madison to support the Virginia Resolutions

- US Presidents on US postage stamps

- List of Presidents of the United States

- List of Presidents of the United States who owned slaves

- List of Presidents of the United States, sortable by previous experience

References

- ^ Kane, Joseph; et al. (2001). Facts About the Presidents. H.W. Wilson. p. 590.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 12

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 62.

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 5.

- ^ Kolchin, Peter (1993). American Slavery, 1619–1877. Whill and Wang. p. 28.

- ^ Boyd-Rush, Dorothy. "Molding a founding father". Montpelier. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ "The Life of James Madison". The Montpelier Foundation. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Mills, W. Jay (2002). "Historic Houses of New Jersey". GET NJ. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Brennan, Daniel. "Did James Madison suffer a nervous collapse due to the intensity of his studies?". Princeton University, Mudd Manuscript Library Blog. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 56.

- ^ Hoffer, Peter Charles (2006). "The Brave New World: A History of Early America". Johns Hopkins Univ. Press. p. 363. ISBN 9780801884832. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ James H. Hutson (2003). Forgotten Features of the Founding: The Recovery of Religious Themes in the Early American Republic. Lexington Books. p. 156. ISBN 9780739105702.

- ^ Miroff, Bruce; et al. (2011). "Debating Democracy: A Reader in American Politics". Cengage Learning. p. 149. ISBN 9780495913474. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Corbett, Michael (2013). "Politics and Religion in the United States". Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 9781135579753. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 47.

- ^ a b Stagg, J.A. (ed.). "James Madison: Life Before the Presidency". Univ. of Virginia Miller Center. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Wills 2002, p. 12-13

- ^ Wills 2002, p. 17-18

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 57.

- ^ Wills 2002, p. 17-19.

- ^ Wills 2002, p. 19-24

- ^ a b c Wood 2011, p. 104

- ^ Bernstein 1987, pp. 11–12, 81–109.

- ^ Rutland 1987, p. 14.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Rutland 1987, pp. 14–21.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Stewart 2007, p. 181.

- ^ Rutland 1987, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d Wood 2011, p. 183.

- ^ Stewart 2007, p. 182.

- ^ Bernstein 1987, p. 199.

- ^ Wills 2002, p. 29-30.

- ^ Rossiter, Clinton, ed. (1961). The Federalist Papers. Penguin Putnam, Inc. pp. ix, xiii.

- ^ Wills 2002, p. 31-35.

- ^ a b c Labunski 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Wills 2002, p. 35-37.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 135.

- ^ a b c Grigsby, Hugh Blair (1890). Brock, R.A. (ed.). The History of the Virginia Federal Convention of 1788. Vol. 1. Virginia Historical Society. pp. 344–46.

- ^ a b c Wills, Gary, ed. (1982). The Federalist Papers By Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay. Bantom Books. pp. 276–78.

- ^ Banning, Lance. "James Madison: Federalist". Library of Congress. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ Madison, James (July 20, 1788). "Letter to Alexander Hamilton". Archived from the original on April 12, 2001. Retrieved April 12, 2001.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ DeRosa, Marshall L., ed. (1998). The Politics of Dissolution. Transaction Publishers. pp. 58–59. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Labunski 2006, pp. 148–50.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Matthews 1995, p. 130.

- ^ "James Madison Debates a Bill Of Rights". National Humanities Center. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 180.

- ^ Labunski 2006, pp. 195–97.

- ^ "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875, Annals of Congress, House of Representatives, 1st Congress, 1st Session". The Library of Congress. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 217.

- ^ Hutchinson, William T.; et al., eds. (1962). "The Papers of James Madison". University of Chicago Press. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor-last=(help) - ^ Labunski 2006, p. 237.

- ^ Labunski 2006, p. 232.

- ^ Adamson, Barry (2008). Freedom of Religion, the First Amendment, and the Supreme Court: How the Court Flunked History. Pelican Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 9781455604586. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ Graham, John Remington (2009). Free, Sovereign, and Independent States: The Intended Meaning of the American Constitution. Pelican Publishing. pp. 193–94. ISBN 9781455604579. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ "The Charters of Freedom: The Bill of Rights". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ Thomas, Kenneth R., ed. (2013). "The Constitution of the United States of America: Analysis of Cases Decided by the Supreme Court of the U.S." (PDF). GPO. p. 49. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ Varg, Paul A. (1963). Foreign Policies of the Founding Fathers. Michigan State Univ. Press. p. 74.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 38–44.

- ^ Derthick, Martha (1999). Dilemmas of Scale in America's Federal Democracy. Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-521-64039-8. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ Hamilton, Alexander (2001). Writings. Library of America. p. 738.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 43-.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b c Chernow, Ron. (2004). Alexander Hamilton. Penguin. pp. 571–74. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Wood, Gordon S. (2006). "Is there a James Madison Problem? in "Liberty and American Experience in the Eighteenth Century", Womersley, David (ed.)". Liberty Fund. p. 425. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ^ Rosen, Gary (1999). American Compact: James Madison and the Problem of the Founding. University Press of Kansas. pp. 2–4, 6–9, 140–75.

- ^ Banning 1995, pp. 7–9, 161, 165, 167, 228–31, 296–98, 326–27, 330–33, 345–46, 359–61, 371 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBanning1995 (help).

- ^ Banning 1995, pp. 78–79 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBanning1995 (help).

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 377.

- ^ "Book of Members, American Academy of Arts and Sciences" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ Taylor, Elizabeth Dowling (2012). A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madisons. Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Ketcham 1990, pp. 419–21

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Perkins, Bradford (1974). Embargo: Alternative to War, in Essays on the Early Republic 1789–1815. Leonard Levy (Ed.). Dryden Press. p. 324.

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 467.

- ^ Rutland 1990, p. 5.

- ^ McCullough, Noah (2006). "The Essential Book of Presidential Trivia". Random House Digital, Inc. p. 21. ISBN 9781400064823. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Rutland 1990, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Rutland 1990, pp. 32–33, 51, 55.

- ^ Rosen 1999, p. 171 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRosen1999 (help).

- ^ Rosen 1999, pp. 171–73 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRosen1999 (help).

- ^ Peterson, Merrill D., ed. (1974). "James Madison: A Biography in His Own Words". 2. Newsweek: 356–59.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rutland (1990), p. 13

- ^ Rutland (1990), p. 39

- ^ Bradford Perkins, Prologue to war: England and the United States, 1805–1812 (1961) full text online

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 81–84.

- ^ Rutland (1990), pp. 40–44.

- ^ Wills 2002, p. 62-63

- ^ Paul Langford, The eighteenth century: 1688-1815 (1976) p 228

- ^ Rutland (1990), pp. 44–45.

- ^ Rutland (1990), pp. 46–47

- ^ Rutland (1990), p. 55.

- ^ Rutland (2012), p. 57

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 94–96.

- ^ Norman K. Risjord, "1812: Conservatives, War Hawks, and the Nation's Honor," William And Mary Quarterly, 1961 18(2): 196–210. in JSTOR

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Rutland 1987, pp. 217–24.

- ^ Ketcham (1971), James Madison, pp. 508–09

- ^ Ketcham (1971), James Madison, pp. 509–15

- ^ Stagg, 1983.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Donald R. Hickey, The War of 1812: A Short History (U. of Illinois Press, 1995)

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Thomas Fleming, "Dolley Madison Saves The Day" Smithsonian 40#12 (2010): 50-56.

- ^ Anthony Pitch, The Burning of Washington: The British Invasion of 1814 (2013).

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore, The Naval War of 1812, pp. 147–52, The Modern Library, New York, NY.

- ^ Rowen, Bob, "American Privateers in the War of 1812," paper presented to the New York Military Affairs Symposium, Graduate Center of the City University of New York, 2001, revised for Web publication, 2006-8 (http://nymas.org/warof1812paper/paperrevised2006.html), retrieved 6-6-11.

- ^ David Stephen Heidler; Jeanne T. Heidler (2002). The War of 1812. p. 46.

- ^ "The Star-Spangled Banner and the War of 1812," Encyclopedia Smithsonian (http://www.si.edu/Encyclopedia_SI/nmah/starflag.htm), retrieved 3-10-08.

- ^ Wills 2002, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Reilly, Robin, The British at the Gates: The New Orleans Campaign in the War of 1812, 1974.

- ^ "Second War of American Independence," America's Library Web site (http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/madison/aa_madison_war_1.html) retrieved, 6-6-11.

- ^ Rutland (1988), p. 188

- ^ Piehler, G. Kurt, ed. (July 24, 2013). "Benefits, Veteran". Encyclopedia of Military Science. SAGE Publications. p. 220. ISBN 9781452276328. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madison's Veto of the Bonus Bill, March 3, 1817". Constitution Society. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ Banning, Lance, ed. (2004). "Liberty and Order: The First American Party Struggle". Liberty Fund.

- ^ Rutland 1990, p. 20.

- ^ a b Rutland 1990, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d Rutland 1990, pp. 199–200.

- ^ a b Jennings, Paul (1865). A Colored Man's Reminiscences of James Madison. George C. Beadle. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ Wills 2002, p. 163.

- ^ Wills 2002, p. 162.

- ^ McCoy 1989, p. 151.

- ^ Keysaar 2009, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chambers, Douglas B. (2005). Murder at Montpelier. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 138139.

- ^ a b c McCoy 1989, p. 252.

- ^ Gutzman, Kevin R. C. (2007). Virginia's American Revolution: From Dominion to Republic, 1776–1840. Lexington Books. pp. 163–91.

- ^ Denslow, William R. (1957). 10,000 Famous Freemasons, Vol. 3. Macoy Publishing & Masonic Supply Co., Inc. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ Mercer, John Francis. "To James Madison from John Francis Mercer". National Archives: Founders Online. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ Madison, James. "James Madison to Stephen Bates". Founders Early Access. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ Madison, James (1817). "Detached Memoranda". Founders Constitution. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ Ketcham 1990, p. 4.

- ^ The Life of James Madison | Montpelier - James Madison's Montpelier

- ^ Wills 2002, p. 164.

- ^ Quinn, Michael, "Preserving a Legacy: Montpelier Will be Showcase for Madison", Richmond Times Dispatch, December 5, 2004.

Sources

- Banning, Lance (1995). Jefferson & Madison: Three Conversations from the Founding. Madison House.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Banning, Lance (1995). The Sacred Fire of Liberty: James Madison and the Founding of the Federal Republic. Cornell University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bernstein, Richard B. (1987). Are We to be a Nation?; The Making of the Constitution. Harvard Univ. Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ketcham, Ralph (1990). James Madison: A Biography. Univ. of Virginia Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), scholarly biography; paperback ed. - Keysaar, Alexander (2009). The Right to Vote. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-02969-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Labunski, Richard (2006). James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights. Oxford Univ. Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McCoy, Drew R. (1989). The Last of the Fathers: James Madison and the Republican Legacy. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Matthews, Richard K. (1995). If Men Were Angels : James Madison and the Heartless Empire of Reason. University Press of Kansas.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rosen, Gary (1999). American Compact: James Madison and the Problem of Founding. University Press of Kansas.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rutland, Robert A. (1987). James Madison: The Founding Father. Macmillan Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-02-927601-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rutland, Robert A. (1990). The Presidency of James Madison. Univ. Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0700604654.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) scholarly overview of his two terms. - Rutland, Robert A., ed. (1994). James Madison and the American Nation, 1751–1836: An Encyclopedia. Simon & Schuster.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stewart, David (2007). The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution. Simon and Schuster.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wills, Garry (2002). James Madison. Times Books. ISBN 0-8050-6905-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Short bio. - Wood, Gordon S. (2011). The Idea of America: Reflections on the Birth of the United States. The Penguin Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

Biographies

- Brant, Irving (1952). "James Madison and His Times". American Historical Review. 57 (4): 853–70.

- Brant, Irving (1941–1961). James Madison. 6 volumes., the standard scholarly biography