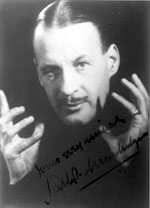

Jasper Maskelyne

Jasper Maskelyne | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1902 London, England |

| Died | 1973 (aged 70-71) |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Stage magician |

| Known for | Stories of wartime exploits |

| Parent(s) | Nevil Maskelyne Ada Mary Ardley |

Jasper Maskelyne (1902–1973) was a British stage magician in the 1930s and 1940s. He was one of an established family of stage magicians, the son of Nevil Maskelyne and a grandson of John Nevil Maskelyne. He is most remembered, however, for his entertaining accounts of his work for British military intelligence during the Second World War, in which he claims that he created large-scale ruses, deception, and camouflage.

Stage magician

Maskelyne was a successful stage magician. His 1936 Book of Magic describes a range of stage tricks, including sleight of hand, card and rope tricks, and illusions of "mind-reading".[1][2]

A 1937 Pathé film, The Famous Illusionist, was made of Maskelyne, looking dapper and apparently eating a boxful of razor blades, one at a time.[3]

Wartime trickery

Maskelyne joined the Royal Engineers when the Second World War broke out, thinking that his skills could be used in camouflage. A story runs that he convinced sceptical officers by creating the illusion of a German warship on the Thames using mirrors and a model.[4]

Maskelyne was trained at the Camouflage Development and Training Centre at Farnham Castle in 1940. He found the training boring, asserting in his book that "a lifetime of hiding things on the stage" had taught him more about camouflage "than rabbits and tigers will ever know".[5] The camoufleur Julian Trevelyan commented that he "entertained us with his tricks in the evenings" at Farnham, but that Maskelyne was "rather unsuccessful" at actually camouflaging "concrete pill-boxes".[6]

Brigadier Dudley Clarke, the head of the 'A' Force deception department, recruited Maskelyne to work for MI9 in Cairo. He created small devices intended to assist soldiers to escape if captured and lectured on escape techniques.[7] These included tools hidden in cricket bats, saw blades inside combs, and small maps on objects such as playing cards.[7]

Maskelyne was then briefly a member of Geoffrey Barkas's camouflage unit at Helwan, near Cairo, which was set up in November 1941. He was made head of the subsidiary "Camouflage Experimental Section" at Abbassia. By February 1942 it became clear that this command was not successful, and so he was "transferred to welfare"—in other words, to entertaining soldiers with magic tricks.[6][8][9] Peter Forbes writes that the "flamboyant" magician's contribution was[9]

either absolutely central (if you believe his account and that of his biographer) or very marginal (if you believe the official records and more recent research).[9]

His nature was "to perpetuate the myth of his own inventive genius, and perhaps he even believed it himself".[9] However, Clarke had encouraged Maskelyne to take credit for two reasons: as cover for the true inventors of the dummy machinery and to encourage confidence in these techniques amongst Allied high command.[7]

Maskelyne's book about his exploits, Magic: Top Secret, ghost-written, was published in 1949. Forbes describes it as lurid, with "extravagant claims of cities disappearing, armies re-locating, dummies proliferating (even submarines)—all as a result of his knowledge of the magic arts". Further, Forbes notes, the biography of Maskelyne by David Fisher was "clearly under the wizard's spell".[9] In his book, Maskelyne claims his team produced[10]

dummy men, dummy steel helmets, dummy guns by the ten thousand, dummy tanks, dummy shell flashes by the million, dummy aircraft...[10]

Reception

A study by Richard Stokes argues that much of the story concerning the involvement of Maskelyne in counterintelligence operations as described in the book "Magic: Top Secret" was pure invention and that no unit called the "Magic Gang" ever existed. Maskelyne's role in the deception war was marginal.[11][12]

Christian House, reviewing Rick Stroud's book The Phantom Army of Alamein in The Independent, describes Maskelyne as "one of the more grandiose members" of the Second World War desert camouflage unit and "a chancer tasked with experimental developments, who fogged his own reputation as much as any desert convoy".[13][14]

David Hambling, writing on Wired,[15] critiques David Fisher's uncritical acceptance of Maskelyne's stories: "A very colorful account of Maskelyne’s role is given in the book The War Magician—reading it you might think he won the war single-handed". Hambling denies Maskelyne's supposed concealment of the Suez Canal: "[I]n spite of the book's claims, the dazzle light[s] were never actually built (although a prototype was once tested)".[15]

In 2002 The Guardian wrote: "Maskelyne received no official recognition. For a vain man this was intolerable and he died an embittered drunk. It gives his story a poignancy without which it would be mere chest-beating".[16]

Works

- Maskelyne, Jasper; Groom, Arthur (1936), Maskelyne's Book of Magic, Harrap

- Maskelyne, Jasper; Stuart, Frank S. (1949), Magic: Top Secret, Stanley Paul

References

- ^ Maskelyne & Groom 1936

- ^ "Maskelyne's Book of Magic by Jasper Maskelyne and Arthur Groom". Stella & Rose's Books. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Jasper Maskelyne 1937". The Famous Illusionist. British Pathé. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ Fisher 1985

- ^ Newark 2007, p. 96

- ^ a b Newark 2007, p. 101

- ^ a b c Mure 1980, p. 95

- ^ Middle East Camouflage Report No. 1. War Office. 28 February 1942.

- ^ a b c d e Forbes 2009, p. 156, 158–159

- ^ a b Maskelyne & Stuart 1949

- ^ In a series of twenty-one articles published between November 1997 and October 2005 in the magazine Genii Magic Journal (Sydney, Australia), magician Richard Stokes criticizes The War Magician, contextualizing David Fisher’s account within contemporary literary and military sources and with reference to the recollections of Jasper Maskelyne’s surviving son, Alistair Maskelyne.

- ^ Stokes, Richard J. "Jasper Maskelyne". The War Magician. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ House, Christian (21 October 2012). "The Phantom Army of Alamein, By Rick Stroud". Wartime smoke and mirrors. The Independent. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ Stroud 2012

- ^ a b Hambling, David (17 May 2008). "Secret Strobelight Weapons of World War II". Wired. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ The Guardian 28 June 2002

Further reading

- Fisher, David (1985), The War Magician: The True Story of Jasper Maskelyne, Corgi

- Forbes, Peter (2009), Dazzled and Deceived: Mimicry and Camouflage, Yale, pp. 158–159

- Latimer, Jon (2001), Deception in War, John Murray

- Mure, David (1980). Master of deception: tangled webs in London and the Middle East. W. Kimber. ISBN 0718302575.

- Newark, Tim (2007), Camouflage, Thames and Hudson, with Imperial War Museum

- Stroud, Rick (2012), The Phantom Army of Alamein: How the Camouflage Unit and Operation Bertram Hoodwinked Rommel, Bloomsbury