List of Mayflower passengers

This is a list of the passengers on board the Mayflower during its trans-Atlantic voyage of September 6 – November 9, 1620, the majority of them becoming the settlers of Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts. Of the passengers, 37 were members of a separatist Puritan congregation in Leiden, The Netherlands (also known as Brownists), who were seeking to establish a colony in the New World[1] where they could preserve their English identities but practice their religion without interference from the English government or church.[2] The Mayflower launched with 102 passengers, 74 male and 28 female, and a crew headed by Master Christopher Jones. About half of the passengers died in the first winter. Many Americans can trace their ancestry back to one or more of these individuals who have become known as the Pilgrims.

Members of the Leiden, Holland Congregation[edit]

Note: An asterisk on a name indicates those who died in the winter of 1620–21.

- Allerton, Isaac (possibly Suffolk).[3][self-published source?]

- Mary (Norris) Allerton*, wife (Newbury, Berkshire)[4]

- Bartholomew Allerton, 7, son (Leiden, Holland).

- Remember Allerton, 5, daughter (Leiden).

- Mary Allerton, 3, daughter (Leiden). She died in 1699, the last surviving Mayflower passenger.[5]

- Bradford, William (Austerfield, Yorkshire).

- Dorothy (May) Bradford*, wife (Wisbech, Isle of Ely, Cambridgeshire).

- Brewster, William (possibly Nottingham).[6][self-published source?]

- Mary Brewster, wife.

- Love/Truelove Brewster, 9, son (Leiden).

- Wrestling Brewster, 6, son (Leiden).

- Carver, John (possibly Yorkshire).[7][self-published source?]

- Katherine (Leggett) (White) Carver, wife (probably Sturton-le-Steeple, Nottinghamshire).

- Chilton, James* (Canterbury, Kent).[8][self-published source?][9][self-published source]

- Mrs. (James) Chilton*, wife.

- Mary Chilton, 13, daughter (Sandwich, Kent).

- Cooke, Francis.

- John Cooke, 13, son (Leiden).

- Cooper, Humility, 1, (probably Leiden) baby daughter of Robert Cooper, in company of her aunt Ann Cooper Tilley, wife of Edward Tilley[10]

- Crackstone/Crackston, John* (possibly Colchester, Essex).[11][self-published source?]

- John Crackstone, son.

- Fletcher, Moses* (Sandwich, Kent).[12][self-published source?]

- Fuller, Edward* (Redenhall, Norfolk).[9]

- Fuller, Samuel (Redenhall, Norfolk), (brother to Edward).

- Goodman, John (possibly Northampton).[15][self-published source?]

- Priest, Degory*

- Rogers, Thomas* (Watford, Northamptonshire).

- Joseph Rogers, 17, son (Watford, Northamptonshire).

- Samson, Henry, 16, (Henlow, Bedfordshire) child in company of his uncle and aunt Edward and Ann Tilley.[10]

- Tilley, Edward* (Henlow, Bedfordshire)

- Ann (Cooper) Tilley* (Henlow, Bedfordshire) wife of Edward and aunt of Humility Cooper and Henry Samson.

- Tilley, John* (Henlow, Bedfordshire).

- Joan (Hurst) (Rogers) Tilley*, wife (Henlow, Bedfordshire).

- Elizabeth Tilley, 13, daughter (Henlow, Bedfordshire).

- Tinker, Thomas* (possibly Norfolk).[16][self-published source?]

- Mrs. Thomas Tinker*, wife.

- boy Tinker*, son, died in the winter of 1620.

- Turner, John* (possibly Norfolk).[17][self-published source?]

- boy Turner*, son, died in the winter of 1620.

- boy Turner*, younger son. died in the winter of 1620.

- White, William*[18] William White's sister Bridget was John Robinson's wife. John Robinson was Pastor of the Pilgrim Fathers leading the Separatists since his days at college at Cambridge[19]

- Susanna White, wife, widowed February 21, 1621. She subsequently married Pilgrim Edward Winslow.[18][20]

- Resolved White, 5, son, wife was Judith Vassal.[18]

- Peregrine White, son. Born on board the Mayflower in Cape Cod Harbor in late November 1620. First European born to the Pilgrims in America.[18]

- Williams, Thomas[21][self-published source?]

- Winslow, Edward (Droitwich, Worcestershire).

- Elizabeth (Barker) Winslow*, wife.

Servants of the Leiden Congregation[edit]

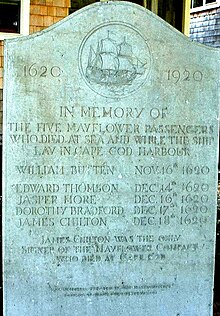

- Butten, William* (possibly Nottingham), "a youth", indentured servant of Samuel Fuller, died during the voyage. He was the first passenger to die on November 16, three days before Cape Cod was sighted.[22][self-published source?]

- ____, Dorothy, teenager, maidservant of John Carver.

- Hooke, John*, (probably Norwich, Norfolk) age 13, apprenticed to Isaac Allerton, died during the first winter.

- Howland, John, (Fenstanton, Huntingdonshire), about 21, manservant and executive assistant for Governor John Carver.[23][self-published source?]

- Latham, William, (possibly Lancashire), age 11, servant and apprentice to the John Carver family.[24][self-published source?]

- Minter, Desire, (Norwich, Norfolk), a servant of John Carver whose parents died in Leiden.[25][self-published source?][26][self-published source]

- More, Ellen (Elinor)*, (Shipton, Shropshire),[27][self-published source?] age 8, assigned as a servant of Edward Winslow. She died from illness sometime in November 1620 soon after the arrival of Mayflower in Cape Cod harbor and likely was buried ashore there in an unmarked grave.[28][self-published source]

- More, Jasper*, (Shipton, Shropshire),[27] age 7, indentured to John Carver. He died from illness on board Mayflower on December 6, 1620, and likely was buried ashore on Cape Cod in an unmarked grave.[28]

- More, Richard, (Shipton, Shropshire),[27] age 6, indentured to William Brewster. He is buried in the Charter Street Burial Ground in Salem, Massachusetts. He is the only Mayflower passenger to have his gravestone still where it was originally placed sometime in the mid-1690s. Also buried nearby in the same cemetery were his wives Christian Hunter More and Jane (Crumpton) More.[28][29]

- More, Mary*, (Shipton, Shropshire),[27] age 4[citation needed], assigned as a servant of William Brewster. She died sometime in the winter of 1620/1621. She and her sister Ellen are recognized on the Pilgrim Memorial Tomb in Plymouth.[28]

- Soule, George, (possibly Bedfordshire), 21–25, servant or employee of Edward Winslow.

- Story, Elias*, age under 21, in the care of Edward Winslow.

- Wilder, Roger*, age under 21, servant in the John Carver family.

Passengers recruited by Thomas Weston, of London Merchant Adventurers[edit]

- James Strong

- Billington, John (possibly Lancashire).[30][self-published source?]

- Eleanor Billington, wife.

- John Billington, 16, son.

- Francis Billington, 14, son.

- Britteridge, Richard* (possibly Sussex).[31][self-published source?]

- Browne, Peter (Dorking, Surrey).

- Clarke, Richard*

- Eaton, Francis (Bristol, Gloucestershire/Somerset).[32][self-published source?]

- Sarah Eaton*, wife.

- Samuel Eaton, 1, son.

- Gardiner, Richard (Harwich, Essex).

- Hopkins, Stephen (Upper Clatford, Hampshire).

- Elizabeth (Fisher) Hopkins, wife.

- Giles Hopkins, 12, son by first marriage (Hursley, Hampshire).

- Constance Hopkins, 14, daughter by first marriage (Hursley, Hampshire).

- Damaris Hopkins, 1–2, daughter. (She died soon in Plymouth Colony and her parents later had another daughter with the same name.)

- Oceanus Hopkins, born on board the Mayflower while en route to the New World.

- Margesson, Edmund* (possibly Norfolk).[33][self-published source?]

- Martin, Christopher* 38 (Great Burstead, Essex). Mayflower Governor & Purchasing Agent.

- Mary (Prowe) Martin*, wife.

- Mullins, William* (Dorking, Surrey).

- Alice Mullins*, wife.

- Priscilla Mullins, 18, daughter.

- Joseph Mullins*, 14, son.

- Prowe, Solomon* (Billericay, Essex). Son of Mary Prowe

- Rigsdale, John* (possibly Lincolnshire).[34][self-published source?]

- Alice Rigsdale*, wife.

- Standish, Myles (Standish, Wigan, Lancashire). Military Expert for Colony.

- Rose Standish*, wife.

- Warren, Richard (Hertford, England).

- Winslow, Gilbert (Droitwich, Worcestershire), brother to Pilgrim Edward Winslow but not known to have lived in Leiden.

Servants of Merchant Adventurers passengers[edit]

- Carter, Robert*, (possibly Surrey), teenager, servant or apprentice to William Mullins, shoemaker.

- Doty, Edward, (possibly Lincolnshire) age probably about 21, servant to Stephen Hopkins.

- Holbeck, William*, age likely under 21, servant to William White.

- Langemore, John*, age under 21, servant to Christopher Martin.

- Leister, Edward also spelled Leitster, (possibly vicinity of London), aged over 21, servant to Stephen Hopkins.[35]

- Thompson (or Thomson), Edward*, age under 21, in the care of the William White family, first passenger to die after the Mayflower reached Cape Cod.

Passenger activities and care[edit]

Some families traveled together, while some men came alone, leaving families in England and Leiden. Two wives on board were pregnant; Elizabeth Hopkins gave birth to son Oceanus while at sea, and Susanna White gave birth to son Peregrine in late November while the ship was anchored in Cape Cod Harbor. He is historically recognized as the first European child born in the New England area. One young man died during the voyage, and there was one stillbirth during the construction of the colony.

According to the Mayflower passenger list, just over half of the passengers were Puritan Separatists and their dependents. They sought to break away from the established Church of England and create a society along the lines of their religious ideals. Other passengers were hired hands, servants, or farmers recruited by London merchants, all originally destined for the Colony of Virginia. Four of this latter group of passengers were small children given into the care of Mayflower pilgrims as indentured servants. The Virginia Company began the transportation of children in 1618.[36] Until relatively recently, the children were thought to be orphans, foundlings, or involuntary child labor. At that time, children were routinely rounded up from the streets of London or taken from poor families receiving church relief to be used as laborers in the colonies. Any legal objections to the involuntary transportation of the children were overridden by the Privy Council.[37][38] For instance it has been proven that the four More children were sent to America because they were deemed illegitimate.[39] Three of the four More children died in the first winter in the New World, but Richard lived to be approximately 81, dying in Salem, probably in 1695 or 1696.[40]

The passengers mostly slept and lived in the low-ceilinged great cabins and on the main deck, which was 75 by 20 feet large (23 m × 6 m) at most. The cabins were thin-walled and extremely cramped, and the total area was 25 ft by 15 ft (7.6 m × 4.5 m) at its largest. Below decks, any person over five feet (150 cm) tall would be unable to stand up straight. The maximum possible space for each person would have been slightly less than the size of a standard single bed.[41]

Passengers would pass the time by reading by candlelight or playing cards and games such as nine men's morris.[42] Meals on board were cooked by the firebox, which was an iron tray with sand in it on which a fire was built. This was risky because it was kept in the waist of the ship. Passengers made their own meals from rations that were issued daily and food was cooked for a group at a time.[41]

Upon arrival in America, the harsh climate and scarcity of fresh food were exacerbated by the shortness of provisions due to the delay in departure. Living in these extremely close and crowded quarters, several passengers developed scurvy, a disease caused by a deficiency of vitamin C. At the time the use of lemons or limes to counter this disease was unknown, and the usual dietary sources of vitamin C in fruits and vegetables had been depleted, since these fresh foods could not be stored for long periods without their becoming rotten. Passengers who developed scurvy experienced symptoms such as bleeding gums, teeth falling out, and stinking breath.[20] Passengers consumed large amounts of alcohol such as beer with meals. This was known to be safer than water, which often came from polluted sources causing diseases. All food and drink was stored in barrels known as "hogsheads".[20]

No cattle or beasts of draft or burden were brought on the journey, but there were pigs, goats, and poultry. Some passengers brought family pets such as cats and birds. Peter Browne took his large bitch mastiff, and John Goodman brought along his spaniel.[42]

The passenger William Mullins brought 126 pairs of shoes and 13 pairs of boots in his luggage. Other items included oiled leather and canvas suits, stuff gowns and leather and stuff breeches, shirts, jerkins, doublets, neckcloths, hats and caps, hose, stockings, belts, piece goods, and haberdashery. At his death, his estate consisted of extensive footwear and other items of clothing, and made his daughter Priscilla and her husband John Alden quite prosperous.[42][43][44]

Mayflower officers and crew[edit]

According to author Charles Edward Banks, the Mayflower had 14 officers consisting of the master, four mates, four quartermasters, surgeon, carpenter, cooper, cook, boatswain, and gunner, plus about 36 men before the mast for a total of 50. More recent authors estimate a crew of about 30. The entire crew stayed with the Mayflower in Plymouth through the winter of 1620–21, and about half of them died. The surviving crew returned to London on the Mayflower on April 5, 1621.[45] [46][self-published source?][47][self-published source][48][49]

Crew members per various sources[edit]

Banks states that the crew totaled 36 men before the mast and 14 officers, making a total of 50. Nathaniel Philbrick estimates between 20 and 30 sailors in her crew whose names are unknown. Nick Bunker states that Mayflower had a crew of at least 17 and possibly as many as 30. Caleb Johnson states that the ship carried a crew of about 30 men, but the exact number is unknown.[46][45] [49][48]

Officers and crew[edit]

- Captain: Christopher Jones. About age 50, of Harwich, a seaport in Essex, England, which was also the port of his ship Mayflower. He and his ship were veterans of the European cargo business, often carrying wine to England, but neither had ever crossed the Atlantic. By June 1620, he and Mayflower had been hired for the Pilgrims voyage by their business agents in London, Thomas Weston of the Merchant Adventurers and Robert Cushman.[50][51]

- Masters Mate: John Clark (Clarke), Pilot. By age 45 in 1620, Clark already had greater adventures than most other mariners of that dangerous era. His piloting career began in England about 1609. In early 1611, he was pilot of a 300-ton ship on his first New World voyage, with a three-ship convoy sailing from London to the new settlement of Jamestown in Virginia. Two other ships were in that convoy, and the three ships brought 300 new settlers to Jamestown, going first to the Caribbean islands of Dominica and Nevis. While in Jamestown, Clark piloted ships in the area carrying various stores. During that time, he was taken prisoner in a confrontation with the Spanish; he was taken to Havana and held for two years, then transferred to Spain where he was in custody for five years. In 1616, he was finally freed in a prisoner exchange with England. In 1618, he was back in Jamestown as pilot of the ship Falcon. Shortly after his return to England, he was hired as pilot for Mayflower in 1620.[52][53][54]

- Masters Mate: Robert Coppin, Pilot. Coppin had prior New World experience; he previously hunted whales in Newfoundland and sailed the coast of New England.[52][55] He was an early investor in the Virginia Company, being named in the Second Virginia Charter of 1609. He was possibly from Harwich in Essex, the hometown of Captain Jones.

- Masters Mate: Andrew Williamson

- Masters Mate: John Parker[52]

- Surgeon: Doctor Giles Heale. The surgeon on board Mayflower was never mentioned by Bradford, but his identity was well established. He was essential in providing comfort to all who died or were made ill that first winter. He was a young man from Drury Lane in the parish of St. Giles in the Field, London who had completed his apprenticeship with the Barber-Surgeons in the previous year. On February 21, 1621, he was a witness to the death-bed will of William Mullins. He survived the first winter and returned to London on Mayflower in April 1621, where he began his medical practice and worked as a surgeon until his death in 1653.[56][57][58]

- Cooper: John Alden. Alden was a 21-year-old from Harwich in Essex and a distant relative of Captain Jones. He hired on apparently while Mayflower was anchored at Southampton Waters. He was responsible for maintaining the ship's barrels, known as hogsheads, which were critical to the passengers' survival and held the only source of food and drink while at sea; tending them was a job which required a crew member's attention. Bradford noted that Alden was "left to his own liking to go or stay" in Plymouth rather than return with the ship to England. He decided to remain.[59][60]

- Quartermaster: (names unknown), 4 men. These men were in charge of maintaining the ship's cargo hold, as well as the crew's hours for standing watch. Some of the “before the mast" crewmen may also have been in this section. These quartermasters were also responsible for fishing and maintaining all fishing supplies and harpoons. The names of the quartermasters are unknown, but it is known that three of the four men died the first winter.[52][54]

- Cook: (Gorge Hurst). He was responsible for preparing the crew's meals and maintaining all food supplies and the cook room, which was typically located in the ship's forecastle (front end). The unnamed cook died the first winter.[61]

- Master Gunner: (name unknown). He was in charge of the ship's guns, ammunition, and powder. Some of those "before the mast" were likely in his charge. He is recorded as going on an exploration on December 6, 1620, and was "sick unto death and so remained all that day, and the next night". He died later that winter.[62]

- Boatswain: (name unknown). He was the person in charge of the ship's rigging and sails, the anchors, and the ship's longboat. The majority of the crew members "before the mast" were most likely under his supervision, working the sails and rigging. The operation of the ship's shallop was also probably under his control, a light open boat with oars or sails (see seaman Thomas English). William Bradford made this comment about the boatswain: "the boatswain... was a proud young man, who would often curse and scoff at the passengers, but when he grew weak they had compassion on him and helped him." But despite such assistance, the unnamed boatswain died the first winter.[61]

- Carpenter: (name unknown). He was responsible for making sure that the hull was well-caulked and the masts were in good order. He was the person responsible for maintaining all areas of the ship in good condition and being a general repairman. He also maintained the tools and all necessary items to perform his carpentry tasks. His name is unknown, but his tasks were quite important to the safety and seaworthiness of the ship.[52][63]

- Swabber: (various crewmen). This was the lowliest position on the ship, responsible for cleaning (swabbing) the decks. The swabber usually had an assistant who was responsible for cleaning the ship's beakhead (extreme front end), which was also the crew's toilet.[64]

Known Mayflower seamen[edit]

- John Allerton: A Mayflower seaman who was hired by the company as labor to help in the Colony during the first year, then to return to Leiden to help other church members seeking to travel to America. He signed the Mayflower Compact. He was a seaman on ship's shallop with Thomas English on exploration of December 6, 1620, and died sometime before Mayflower returned to England in April 1621.[65][66]

- ____ Ely: A Mayflower seaman who was contracted to stay for a year, which he did. He returned to England with fellow crewman William Trevor on the Fortune in December 1621. Genealogist Jeremy Bangs believes that his name was either John or Christopher Ely (or Ellis), both of whom are documented in Leiden, Holland.[67]

- Thomas English: A Mayflower seaman who was hired to be the master of the shallop (see Boatswain) and to be part of the company. He signed the Mayflower Compact. He was a seaman on the ship's shallop with John Allerton on exploration of December 6, 1620, and died sometime before the departure of Mayflower for England in April 1621. He appeared in Leiden records as "Thomas England".[68][69]

- William Trevore (Trevor): A Mayflower seaman who was hired to remain in Plymouth for one year. One reason for his hiring was his prior New World experience. He was one of those seamen to crew the shallop used in coastal trading. He returned to England with _____ Ely and others on the Fortune in December 1621. In 1623, Robert Cushman noted that Trevor reported to the Adventurers about what he saw in the New World. He did at some time return as master of a ship and was recorded living in Massachusetts Bay Colony in April 1650.[70][71][72]

Unidentified passenger[edit]

- "Master" Leaver: Another passenger not mentioned by Bradford is a person called "Master" Leaver. He was named in Mourt's Relation (London, 1622), under a date of January 12, 1621, as a leader of an expedition to rescue Pilgrims lost in the forest for several days while searching for housing-roof thatch. It is unknown in what capacity he came to Mayflower and his given name is unknown. The title of "Master" indicates that he was a person of some authority and prominence in the company. He may have been a principal officer of Mayflower. No more is known of him; he may have returned to England on Mayflower's April 1621 voyage or died of the illnesses that affected so many that first winter.[73]

Known crew members[edit]

- Christopher Jones – Captain

- John Clarke – First Mate and Pilot

- Robert Coppin – Second Mate and Pilot

- Giles Heale – ship's surgeon, identified with the Separatists. He is not counted as one of the 102 passengers.

- Andrew Williamson – Seaman

- John Parker – Seaman

- Master Leaver – Seaman[74]

Ship crewmen hired to stay one year[edit]

- John Alden – A 21-year-old from Harwich, Essex, the ship's cooper; he was given the choice of remaining in the colony or returning to England and decided to remain.

- John Allerton* – A Mayflower seaman hired as colony labor for one year who was then to return to Leiden to assist church members with travel to America. He died some time before the Mayflower departed for England on April 5, 1621.[66]

- ____ Ely – A Mayflower seaman contracted to stay for one year. He returned to England on the Fortune in December 1621 along with William Trevor. Jeremy Bangs believes that his name was either John or Christopher Ely, or Ellis, who are documented in Leiden records.[67]

- Thomas English* – A Mayflower seaman hired to be master of the ship's shallop. He died sometime before the departure of the Mayflower for England on April 5, 1621.

- William Trevore – A Mayflower seaman with prior New World experience hired to work in the colony for one year. He returned to England on the Fortune in December 1621 along with Ely and others. By 1650, he had returned to New England.

Note: Asterisk on any name indicates those who died in the winter of 1620–21.

Animals on board[edit]

Two dogs are known to have participated in settling Plymouth. In Mourt's Relation, Edward Winslow writes that a female English Mastiff and a small English Springer Spaniel came ashore on the first explorations of Provincetown. The ship was probably also carrying small domestic animals such as goats, pigs, and chickens. Larger domestic animals came later, such as cows and sheep.[75]

See also[edit]

- Mayflower Compact

- Mayflower Compact signatories

- List of Mayflower passengers who died at sea November/December 1620

- List of Mayflower passengers who died in the winter of 1620–21

- The Mayflower Society

References[edit]

- ^ Bradford 1856, p. 24.

- ^ "Who Were the Pilgrims?".

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 29.

- ^ Locations of birth for Mayflower passengers follow Caleb Johnson's list as found at Mayflower History.com Archived 2006-09-05 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 29, 2006.

- ^ Stratton 1986, p. 234.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 91.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 107.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 115.

- ^ a b Division of passengers by category generally follows Appendix I of Saints and Strangers by George F. Willison with some exceptions.

- ^ a b Humility Cooper and Henry Sampson were both children who joined their uncle and aunt Edward and Ann Tilley for the voyage. Willison lists them as "strangers" because they were not members of the church at Leiden; however, as children they would have been under their aunt and uncle who were members of that group.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 130.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 142.

- ^ A genealogical profile of Edward Fuller [1] Archived 2011-11-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pilgrim Village Family Sketch Edward Fuller New England Genealogical Historic Society [2] Archived 2012-11-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 154.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 239.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 243.

- ^ a b c d Ruth Wilder Sherman, CG, FASG, and Robert Moody Sherman, CG, FASG, Mayflower Families Through Five Generations, Family of William White, Vol. 13, 3rd edition (Pub. by General Society of Mayflower Descendants 2006) p. 3.

- ^ "Robinson, John (RBN592J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ a b c Philbrick 2006, p. 104.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 250.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 105.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 198.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 177.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 187.

- ^ A genealogical profile of John Carver (a collaboration of Plimoth Plantation and New England Historic Genealogical Society accessed 2013-04-21) [3] Archived 2012-11-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Johnson 2006, p. 190.

- ^ a b c d David Lindsay, Mayflower Bastard: A Stranger amongst the Pilgrims (New York: St. Martins Press, 2002) p. 27

- ^ Memorial for The More children [4]

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 3.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 73.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 138.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 182.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 200.

- ^ Bradford 1856, p. 455.

- ^ Donald F. Harris, PhD., The Mayflower Descendant (July 1994) vol. 44 no. 2 p. 111

- ^ R.C. Johnson, The Transportation of Vagrant Children from London to Virginia, 1618–1622, in H.S. Reinmuth (Ed.), Early Stuart Studies: Essays in Honor of David Harris Willson, Minneapolis, 1970.

- ^ The Mayflower Descendant (July 2, 1994) vol. 44 no. 2 pp. 110, 111

- ^ Donald F. Harris, The Mayflower Descendants vol 43 (July 1993), vol. 44 (July 1994).

- ^ David Lindsay, Mayflower Bastard: A Stranger amongst the Pilgrims (St. Martins Press, New York, 2002) Introduction

- ^ a b Caffrey, Kate. The Mayflower. New York: Stein and Day, 1974

- ^ a b c Hodgson, Godfrey. A Great and Godly Adventure. Public Affairs: New York, 2006

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 195.

- ^ Banks 2006, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b Banks 2006, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b Johnson 2006, p. 33.

- ^ Stratton 1986, p. 21.

- ^ a b Bunker 2010, p. 31.

- ^ a b Philbrick 2006, p. 25.

- ^ Banks 2006, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Johnson 2006, pp. 25, 28, 31.

- ^ a b c d e Banks 2006, p. 19.

- ^ Bunker 2010, p. 24.

- ^ a b Johnson 2006, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 32.

- ^ Philbrick 2006, p. 24.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 33–34.

- ^ Banks 2006, pp. 7–8, 19.

- ^ Johnson 2006, pp. 34, 46.

- ^ Banks 2006, pp. 7, 19, 27–28.

- ^ a b Johnson 2006, p. 35.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 34.

- ^ Johnson 2006, pp. 34–35.

- ^ In the tradition of the sea, each Monday a crew member was appointed the "liar" or swabber assistant. This person was the first person caught telling a lie the previous week, and the crew would harass him around the main mast with calls of "liar, liar." (Johnson 2006, p. 35)

- ^ Johnson 2006, pp. 71–72, 14.

- ^ a b Stratton 1986, pp. 21, 234.

- ^ a b Stratton 1986, pp. 21, 289.

- ^ Johnson 2006, p. 141.

- ^ Stratton 1986, p. 289.

- ^ Banks 2006, p. 90.

- ^ Johnson 2006, pp. 240–242.

- ^ Stratton 1986, pp. 21, 364.

- ^ Banks 2006, pp. 8–9.

- ^ David Beale, The Mayflower Pilgrims: Roots of Puritan, Presbyterian, Congregationalist, and Baptist Heritage (Greenville, SC: Ambassador-Emerald International, 2000) pp. 121–122

- ^ "Animals".

Sources[edit]

- Banks, Charles Edward Banks (2006). The English ancestry and homes of the Pilgrim Fathers who came to Plymouth on the "Mayflower" in 1620, the "Fortune" in 1621, and the "Anne" and the "Little James" in 1623. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company.

- Mayflower passengers from William Bradford's Of Plymouth Plantation, 1650.

- Bradford, William (1856). Charles Deane (ed.). History of Plymouth Plantation by William Bradford, the second Governor of Plymouth. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Bunker, Nick (2010). Making Haste from Babylon: The Mayflower Pilgrims and their New World, a History. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0307386260.)

- Johnson, Caleb H. (2006). The Mayflower and Her Passengers. Indiana: Xlibris. ISBN 9781462822379.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel (2006). Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community and War. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780670037605.

- Stratton, Eugene Aubrey (1986). Plymouth Colony: Its History and People, 1620–1691. Turner Publishing. ISBN 9781630264031.