John Bapst

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

John Bapst | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st President of Boston College | |

| In office 1863–1869 | |

| Succeeded by | Robert W. Brady |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Johannes Bapst December 17, 1815 La Roche, Switzerland |

| Died | November 2, 1887 (aged 71) Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Resting place | Woodstock College cemetery |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | December 31, 1846 by Étienne Marilley |

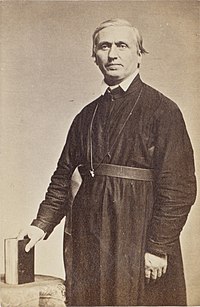

John Bapst SJ (born Johannes Bapst; December 17, 1815 – November 2, 1887) was a Swiss Jesuit missionary and educator who became the first president of Boston College.

Early life[edit]

Bapst was born on December 17, 1815, in La Roche, in the Canton of Fribourg in Switzerland. One of three sons, his parents were prosperous farmers. Bapst attended schools in his village from an early age. At the age of twelve, he began his studies at Collège Saint-Michel in the city of Fribourg, progressing through the classical courses of grammar, humanities, rhetoric, and philosophy.[1]

On September 30, 1835, having completed only the first of his two years of philosophy, Bapst was admitted into the novitiate in Estavayer-le-Lac, and entered the Society of Jesus. After a year, the novitiate moved to Brig-Glis in Valais. That year, Bapst's older brother, Joseph, also entere dthe noviitate in Brig. After twelve years in Jesuit formation, Joseph left the order and eventually became the rector of Collège Saint-Michel. In September 1837, Bapst completed his noviceship and began his philosophical studies at the Jesuit scholasticate in Fribourg. This was followed by one year of studying rhetoric.[2]

In 1840, Bapst became a professor at Collége Saint-Michel, teaching rudiments and grammar for three years.[3] He began his four years of theological studies in 1843, and on December 31, 1846, was ordained a priest by Étienne Marilley, the Bishop of Lausanne and Geneva.[4]

Missionary in Maine[edit]

Following the defeat of the Catholic cantons in the Sonderbund War of 1847, the Jesuits were expelled from Switzerland. Bapst was sent to Notre Dame d'Ay in France to complete his tertianship.[4] In May 1848, the Jesuit provincial superior of Upper Germany directed Bapst that he would become a missionary in the United States. Bapst was greatly upset, desiring neither to work in the Jesuit missions nor move to America.[5] He acquiesced, however, and left for Antwerp, Belgium, from which he sailed to New York City with 40 fellow Swiss Jesuits, arriving in late May.[6]

Old Town[edit]

Despite Bapst speaking neither English nor any Indian language nor being familiar with the customs of the United States, the provincial superior of the Jesuit Maryland province sent Bapst to the mission to the Penobscot Indians in Old Town, Maine,[7][6] where he would remain for three years.[8] He sailed to Boston, Massachusetts, with another Jesuit and then alone onto Maine.[9]

Bapst took charge of the mission on August 7, 1848.[10] The Indian residents of Old Town welcomed Bapst, as they had been without a priest for 20 years.[11] He was able to communicate with the people through one Indian who spoke French.[10] Bapst began to learn their language, and after several months, was able to hear confessions in their native language.[12] He found alcoholism rampant, with public drunkenness and resulting bar fights common. As a result, he created a temperance society, which had many members, and announced that anyone who was found drunk would not be permitted to enter the church without publicly apologizing. The Indians were also engaged in a 20-year-long civil war with another a sect that had broken away.[13] Before long, a cholera epidemic broke out among the town.[14] Bapst viewed the Indian orators highly, writing:[15]

Theirs is a savage eloquence, but I do not believe that in the eloquence of our greatest orators in the national assembly at Paris can there be found anything so natural, strong and just. I was astonished. Their language abounds with figures, and is graceful and delicate. It is nature that speaks, it is true, but nature freed from all the trammels to which overwrought civilization often subjects our greatest orators; it is a robust nature that, unfolding itself like the oak of the forest, is full of life and majesty. Those who represent the Indians as a degenerate race are certainly wrong. Generally, their judgment is sounder, their mind more masculine, their character more energetic and their passions stronger than the whites'.[15]

Eastport[edit]

Unable to broker a peace between the opposing factions, Bapst met limited success in his mission to the Indians in Old Town, and in September 1850, the provincial superior directed him to leave for Eastport, Maine.[16] From there, he would minister to the Irish and French Canadian emigrants,[16] as well as the Indian residents of the Passamaquoddy Pleasant Point Reservation.[17] His ministry encompassed a territory of 200 square miles (520 km2), including 33 missions.[18] He managed at least nine Jesuit assistants, and traveled to these many missions six times per year.[19] By 1852, the Catholic population in the Maine mission number 9,000.[18]

Bapst oversaw the completion of 8 churches by 1852, whose construction had begun in 1848. He also opened St. John's Church in Waterville, St. Gabriel's Church in Winterport, and established a mission in Trescott.[17]

In October 1851, Bapst traveled to Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., where, along the way, he toured the central and southern portions of the Jesuits' Maryland province, visiting their institutions in Boston, Worcester, Massachusetts; New York; Philadelphia; and Frederick, Maryland.[20]

Boston College[edit]

On July 2, 1860, Bapst became the rector of the Jesuit scholasticate,[21] which was then housed in the nascent Boston College's new buildings.[22] On July 10, 1863, the first meeting of the trustees of the newly incorporated college was held, at which Bapst was elected the first president of Boston College, as well as a member of the board of directors, for a term of three years.[23] His presidency began the following month.[24] At the same time, he replaced John McElroy as the pastor of the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola.[25] While at Boston College, Bapst was the confessor to John Bernard Fitzpatrick, the Bishop of Boston, and the majority of priests of the diocese.[26] Throughout Murphy's presidency, the school's prefect was Robert J. Fulton,[27] who had exclusive oversight of its academic affairs.[28]

By November 1863, Boston College and St. Ignatius Church had accrued a significant debt of more than $150,000, and Bapst anticipated a large financial deficit in the coming year.[29] To alleviate this debt, Bapst met with the prominent men of the parish, including Andrew Carney, who pledged $20,00 if the parish raised an equal amount.[30] Within several months, this was achieved, and in total, Bapst raised $62,000.[31]

Boston College officially opened on September 5, 1864, initially with a lower enrollment than anticipated.[32] In total, 62 students enrolled throughout the first year, and 48 of them remained at the end of the year.[33] In 1864, Murphy's title was reduced from rector of the scholasticate to superior, to reflect the small size of the institution.[21] The student body steadily increased throughout the remained of his presidency, numbering 130 students in 1869.[34] Though succeeding, the school continued to struggle financially in its early years.[35]

On August 23, 1869, Bapst's tenure as president came to an end,[28] and he was succeeded by Robert W. Brady. By the end of his presidency, Bapst had reduced the college's debt to $58,000.[36]

Career[edit]

He was sent to minister to the Penobscot Native Americans at Old Town, Maine, who had been without a priest for 20 years after ten of his predecessors were murdered. Initially ignorant of the Abenaki language spoken in the Penobscot Indian Island Reservation he was able to learn it over three (3) years time.

Father Bapst founded several temperance societies in Maine.

In 1850, he left Old Town for Eastport. His work immediately began to attract attention for its results among Catholics and for the number of converts who were brought into the Church. As his missions covered a large extent of territory, he became generally known throughout the state. When the Know-Nothing excitement broke out, he was at Ellsworth. Protestant Yankees were outraged when he denounced the public school system for forcing a Protestant Bible on Catholic children. He moved to Bangor, Maine.

The Ellsworth town meeting passed a resolution threatening him bodily if he returned. He nevertheless returned to the town on a brief visit in October 1854 and was attacked by ruffians, robbed of his watch and money, tarred and feathered, and ridden out of town on a rail. The incident was met with general condemnation across Maine and the rest of New England.[37]

In Bangor, Maine, Father Bapst built St. John's Catholic Church (Bangor, Maine), the first Catholic church in Bangor, which was dedicated in December 1856. He remained there for three years and was then sent to Boston College as rector of what was the house of higher studies for Jesuit scholastics.

He was afterwards superior of all the Jesuit houses of Canada and New York and then superior of a Residence in Providence, Rhode Island.

Bapst died on November 2, 1887, at Mount Hope Retreat in Baltimore, and was buried in the cemetery at Woodstock College.[7]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Woodstock Letters 1888a, p. 218.

- ^ Woodstock Letters 1888a, p. 219.

- ^ Woodstock Letters 1888a, pp. 219–220.

- ^ a b Woodstock Letters 1888a, p. 220.

- ^ Woodstock Letters 1888a, pp. 220–221.

- ^ a b Woodstock Letters 1888a, p. 221.

- ^ a b Woodstock Letters 1887, p. 324.

- ^ Woodstock Letters 1888b, p. 361.

- ^ Woodstock Letters 1888a, p. 222.

- ^ a b Woodstock Letters 1888a, p. 223.

- ^ Herbermann 1907, p. 258.

- ^ Woodstock Letters 1888a, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Woodstock Letters 1888a, p. 224.

- ^ Woodstock Letters 1888a, p. 227.

- ^ a b Woodstock Letters 1888a, p. 225.

- ^ a b Woodstock Letters 1888b, p. 367.

- ^ a b Lapomarda 1977, p. 19.

- ^ a b Woodstock Letters 1889, p. 83.

- ^ Lapomarda 1977, p. 18.

- ^ Woodstock Letters 1888b, p. 371.

- ^ a b Donovan, Dunigan & FitzGerald 1990, p. 34.

- ^ Donovan, Dunigan & FitzGerald 1990, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Donovan, Dunigan & FitzGerald 1990, p. 29.

- ^ Donovan, Dunigan & FitzGerald 1990, p. 27.

- ^ Lapomarda 1977, p. 211.

- ^ Woodstock Letters 1889, p. 68.

- ^ Donovan, Dunigan & FitzGerald 1990, p. 57.

- ^ a b Donovan, Dunigan & FitzGerald 1990, p. 62.

- ^ Donovan, Dunigan & FitzGerald 1990, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Donovan, Dunigan & FitzGerald 1990, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Donovan, Dunigan & FitzGerald 1990, p. 38.

- ^ Donovan, Dunigan & FitzGerald 1990, p. 42.

- ^ Donovan, Dunigan & FitzGerald 1990, p. 44.

- ^ Donovan, Dunigan & FitzGerald 1990, p. 52.

- ^ Donovan, Dunigan & FitzGerald 1990, p. 55.

- ^ Donovan, Dunigan & FitzGerald 1990, p. 63.

- ^ Maine Historical Society, Maine: a history, (1919) Volume 1 pp. 304–305.

Sources[edit]

- Donovan, Charles F.; Dunigan, David R.; FitzGerald, Paul A. (1990). History of Boston College: From the Beginnings to 1990. Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts: University Press of Boston College. ISBN 0-9625934-0-0. Retrieved August 23, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- "Fr. John Bapst: A Sketch". Woodstock Letters. 17 (2): 218–229. July 1888. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Jesuit Online Library.

- "Fr. John Bapst: A Sketch (Continued.)". Woodstock Letters. 17 (3): 361–372. November 1888. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved August 24, 2023 – via Jesuit Online Library.

- "Fr. John Bapst: A Sketch (Continued.)". Woodstock Letters. 18 (1): 83–93. February 1889. Archived from the original on May 26, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Jesuit Online Library.

- "Fr. John Bapst: A Sketch (Continued.)". Woodstock Letters. 20 (1): 61–68. February 1891. Archived from the original on June 10, 2023. Retrieved June 10, 2023 – via Jesuit Online Library.

- Herbermann, Charles George, ed. (1907). The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company. OCLC 56257142. Retrieved May 25, 2023 – via Internet Archive.

- Lapomarda, Vincent A. (1977). The Jesuit Heritage in New England. Worcester, Massachusetts: The Jesuits of Holy Cross College, Inc. ISBN 978-0960629404. Archived from the original on March 22, 2021. Retrieved May 27, 2023 – via CrossWorks.

- Mendizàbal, Rufo (1972). Catalogus defunctorum in renata Societate Iesu ab a. 1814 ad a. 1970 [Catalogue of the dead in a revival of the Society of Jesus from 1814 to 1970] (in Latin). Rome: Jesuit Archives: Central United States. pp. 91–122. OCLC 884102. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved May 26, 2023 – via Jesuit Archives & Research Center.

- "Obituary: Father John Bapst". Woodstock Letters. 16 (3): 324–325. November 1887. Archived from the original on May 25, 2023. Retrieved May 25, 2023 – via Jesuit Online Library.

- 1815 births

- 1887 deaths

- Anti-Catholic riots in the United States

- Anti-Catholicism in Maine

- Presidents of Boston College

- People from the canton of Fribourg

- Swiss emigrants to the United States

- Swiss Jesuits

- 19th-century American Jesuits

- People from Bangor, Maine

- People from Ellsworth, Maine

- 19th-century Swiss Roman Catholic priests

- Boston College people

- Know Nothing

- Catholics from Maine

- Tarring and feathering in the United States

- Pastors of the Church of the Immaculate Conception (Boston, Massachusetts)

- Burials at Woodstock College Cemetery