KV45

| KV45 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of Userhet, Merenkhons and unknown woman | |

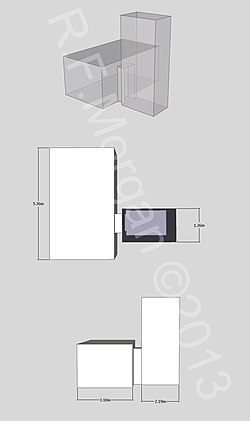

Schematic of KV45 | |

| Coordinates | 25°44′24.2″N 32°36′11.2″E / 25.740056°N 32.603111°E |

| Location | East Valley of the Kings |

| Discovered | February 1902 |

| Excavated by | Howard Carter (1902) Donald P. Ryan (1991, 2005) |

← Previous KV44 Next → KV46 | |

Tomb KV45 is an ancient Egyptian tomb located in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. It was originally used for the burial of the noble Userhet of the Eighteenth Dynasty and was reused by Merenkhons and an unknown woman in the Twenty-second Dynasty. The tomb was discovered and excavated by Howard Carter in 1902, in his role as Chief Inspector of Antiquities, on behalf of Theodore M. Davis.[1] The tomb was later re-investigated by Donald P. Ryan of the Pacific Lutheran University Valley of the Kings Project in 1991 and 2005.[2]

Location and discovery[edit]

KV45 is located in a small wadi that runs east from the main valley and is adjacent to KV44.[1] The tomb was discovered in February 1902 in the course of excavations sponsored by the American millionaire Theodore Davis. In the January Gaston Maspero and Carter had identified promising locations for exploration in the main valley. Having encountered nothing in the spans between KV2 and KV7, and the mouth of the small valley and KV5, excavation shifted to clearing the small valley itself. Running a trench the entire width of the valley excavation advanced up the valley and in the vicinity of KV28 and next to KV44, which was investigated the previous year, an intact tomb was discovered. The burial was opened on 25 February 1902 when Davis returned from Aswan.[1]

Layout and contents[edit]

The tomb consists of a vertical shaft 3 metres (9.8 ft) deep ending in a small chamber which, when found, was a third full of debris. It contained an intact burial dating to the Twenty-second Dynasty. Water had evidently penetrated the tomb in the past as Carter noted that it had "been completely destroyed by rain water."[1] The tomb contained the burials of a man and a woman, each interred in a set of two nested coffins, and accompanied by two boxes of clay ushabti; the remains of floral wreaths were scattered around. The coffins and mummies were in very poor condition, with only the face of one of the man's coffins being salvaged. The man was identified from the titles on a small black limestone heart scarab as Merenkhons, Doorkeeper of the House of Amun; nothing identifiable was found on the mummy of the woman. As these burials sat on top of the fill, they were clearly not the original occupants. Of the presumed original owner, Userhet, Overseer of the Fields of Amun, only fragments of alabaster canopic jars bearing his name were found.[1][3]

Re-investigation[edit]

In 1991 the tomb was re-investigated by the Pacific Lutheran University Valley of the Kings Project headed by Donald P. Ryan. It became apparent that apart from removing the heart scarab and male coffin face, Carter had left everything as it was found. Careful excavation recovered all remaining pieces of the double wooden coffin sets, including the face of the woman's coffin. Eighty-eight ushabti fragments were also recovered.[2] Additionally, the remains of two further individuals were found; these were presumably the original occupants of the tomb.[4]

The project resumed in 2005, and found that water had penetrated the tomb, probably during the 1994 floods. Diversion walls constructed by the project had likely spared the tomb from far worse flood inundation. All artefacts from KV45 and KV44, barring pottery and human remains, were moved to KV21 for protection from further flooding.[2]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Carter, Howard (1903). "Report on General Work Done in the Southern Inspectorate". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. IV. Le Service: 43–50. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Ryan, Donald P. (2007). "Pacific Lutheran University Valley of the Kings Project: Work Conducted during the 2005 Field Season". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. 81: 345–356.

- ^ Porter, Bertha; Moss, Rosalind (1964). Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings Volume I: The Theban Necropolis, Part 2. Royal Tombs and Smaller Cemeteries. Griffith Institute. p. 563. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Ryan, Donald P. (1994). "Exploring the Valley of the Kings". Archaeology. 47 (1): 52–59. ISSN 0003-8113. JSTOR 41770637. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

External links[edit]

- Theban Mapping Project: KV45 includes detailed maps of most of the tombs.