Khokhar

| Khokhar | |

|---|---|

| Jāti | Jat, Rajput |

| Religions | Predominantly (minority |

| Languages | Punjabi, Haryanvi, Hindi |

| Country | |

| Region | Punjab, Haryana |

| Ethnicity | Punjabi |

| Family names | yes |

Khokhar is a historical Punjabi tribe primarily native to the Pothohar Plateau of Pakistani Punjab. Khokhars are also found in the Indian states of Punjab and Haryana.[1] Khokhars predominantly follow Islam, having converted to Islam from Hinduism after coming under the influence of Baba Farid.[1][2][3]

History

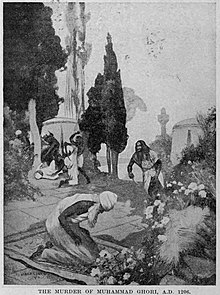

The word "Khokhar" itself is of Persian origin and means "bloodthirsty". In 1204-1205, the Khokhars revolted under their leader and conquered and plundered Multan, Lahore and blocked the strategic roads between Punjab and Ghazni. According to Tarikh-i-Alfi, traders had to follow a longer route due to the depradations of the Khokhars, under Raisal, who used to plunder and harass the inhabitants in such a way that not a single soul could pass along it.[4] As Qutubuddin Aibak was not able to handle the rebellion himself,[5] Muhammad of Ghor undertook many campaigns against the Khokhars and defeated them in his final battle fought on the bank of Jhelum and subsequently ordered a general massacre of their populace. While returning back to Ghazna, he was assassinated at Dhamiak located in the Salt Range in March 1206 by the Ismailis whom he persecuted during his reign.[6][7] Some later acoounts attributed the assassination of Muhammad of Ghor to the Hindu Khokhars, however these later accounts are not corroborated by early Persian chroniclers who confirmed that his assassins were from the rival Ismāʿīlīyah sect of Shia Muslims.[8] Dr. Habibullah, based on Ibn-i-Asir's statement, is of the opinion that the deed was of a joint Bātini and Khokar affair.[9] According to Agha Mahdi Husain, the Khokhars too might be called Malahida in view of their recent conversion to Islam.[10][11]

During his final campaign, Muhammad also took many of the Khokars as prisoners who were later converted to Islam.[12] During the same expedition, he also converted many other Khokhars and Buddhists who lived between Ghazna and Punjab. According to the Persian chroniclers "about three or four lakhs of infidels who wore the sacred thread were made Muslamans during this campaign".[13] The 16th century historian Ferishta states - "most of the infidels who resided between the mountains of Ghazna and Indus were converted to the true faith (Islam)".[12]

Under Delhi Sultanate

In 1240 CE, Razia, daughter of Shams-ud-din Iltutmish, and her husband, Altunia, attempted to recapture the throne from her brother, Muizuddin Bahram Shah. She is reported to have led an army composed mostly of mercenaries from the Khokhars of Punjab.[14] From 1246 to 1247, Balban mounted an expedition as far as the Salt Range to eliminate the Khokhars which he saw as a threat.[15]

Although Lahore was controlled by the government in Delhi in 1251, it remained in ruins for the next twenty years, being attacked multiple times by the Mongols and their Khokhar allies.[16] Around the same time, a Mongol commander named Hulechu occupied Lahore, and forged an alliance with Khokhar chief Gul Khokhar, the erstwhile ally of Muhammad's father.[17]

The Khokhars, who were among the earliest to convert to Islam, were further converted due to the influence of Baba Farid, who gave their daughters in marriage to the families of the head of the shrine. The Jawahar-i-Faridi records out of the twenty-three of such marriages, fourteen were Khokhars, whose names were prefixed with Malik, which implied an association with political power. The names of the tribes associated with the shrine of Pakpattan included twenty clans, the Khokhars, Khankhwanis, Bahlis, Adhkhans, Jhakarvalis, Yakkan, Meharkhan, Siyans, Khawalis, Sankhwalis, Siyals, Baghotis, Bartis, Dudhis, Joeyeas, Naharwanis, Tobis and Dogars.[18]

Ghazi Malik founded the Tughlaq Dynasty in Delhi by a rebellion with the support of the Khokhar tribes who were placed as advance-guards of the army.[19] The Khokhars enjoyed the favours of the Tughluqs for a considerable period till the revolt of Gul Khokhar. The tribes then took the opportunity to raise the standard of rebellion whenever the chance offered itself.[20] Ainul Mulk Multani, the governor of Multan, exclaimed anxiety about his family and his dependents' journey from Ajodhan (Pakpattan) to Multan, since an uprising of the Khokhars had made the road unsafe.[21] The Khokhars conquered Lahore in 1342 during the reign of Muhammad bin Tughlaq and again in 1394 led by the chief Shaikha Khokhar, the former governor of Lahore during the reign of Sultan Mahmud Tughlaq.[22] They grew powerful during the period of Firuz Shah, who led an expedition against the Khokhar chief in Sambhal.[23] Nusrat Khokhar, the governor of Lahore, was one of main important nobles in the Delhi Sultanate along with Sarang Khan, Mallu Iqbal and Muqarrab Khan, the latter who were nobles of convert origin.[24] The governor of Nagaur, Rajasthan, appointed by the Tughlaq dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate was Jalal Khan Khokhar.[25] Jalal Khan Khokhar married the sister of the wife of Rao Chunda, the ruler of the emergent Marwar kingdom.[26]

There are dispute regarding origin of Khizr Khan, the viceroy of Timur in Delhi and founder of the Sayyid dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate. According to some scholars, Khizr Khan was a Khokhar chieftain,[27] who travelled to Samarkand and profited from the contacts he made with the Timurid society.[28]

Independent Chieftains

Mustafa Jasrat Khokhar (sometimes Jasrath or Dashrath)[29] was the son of Shaikha Khokhar. He became leader of the Khokhars after the death of Shaikha Khokhar. Later, he returned to Punjab. He supported Shahi Khan in the war for control of Kashmir against Ali Shah of Sayyid dynasty and was later rewarded for his victory. Later, he attempted to conquer Delhi, after the death of Khizr Khan. He succeeded only partially, while winning campaigns at Talwandi and Jullundur, he was hampered by seasonal rains in his attempt to take over Sirhind.[30]

Colonial era

In reference to the British Raj's recruitment policies in the Punjab Province of colonial India, vis-à-vis the British Indian Army, Tan Tai Yong remarks:

The choice of Muslims was not merely one of physical suitability. As in the case of the Sikhs, recruiting authorities showed a clear bias in favor of the dominant landowning tribes of the region, and recruitment of Punjabi Muslims was limited to those who belonged to tribes of high social standing or reputation - the "blood proud" and once politically dominant aristocracy of the tract. Consequently, socially dominant Muslim tribes such as the Gakkhars, Janjuas and Awans, and a few Rajput tribes, concentrated in the Rawalpindi and Jhelum districts, ... accounted for more than ninety percent of Punjabi Muslim recruits.[31]

See also

- List of Rulers of Pothohar Plateau

- Tribes and clans of the Pothohar Plateau

- List of Punjabi Muslim tribes

References

Citations

- ^ a b Singh, Kumar Suresh (2003). People of India: Jammu & Kashmir. Anthropological Survey of India. p. xxiii. ISBN 978-81-7304-118-1.

Gujars of this tract are wholly Muslims, and so are the Khokhar who have only a few Hindu families. In early stages the converted Rajputs continued with preconversion practices.

- ^ Surinder Singh (30 September 2019). The Making of Medieval Panjab: Politics, Society and Culture c. 1000–c. 1500. Taylor & Francis. p. 245. ISBN 978-1-00-076068-2. Archived from the original on 13 March 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ Singha, Atara (1976). Socio-cultural Impact of Islam on India. Panjab University. p. 46.

After this period, we do not hear of any Hindu Gakhars or Khokhars, for during the next two or three centuries they had all come to accept Islam.

- ^ Proceedings - Punjab History Conference. Vol. 29–30. Department of Punjab Historical Studies, Punjabi University. 1998. p. 65. ISBN 9788173804601 – via University of Virginia.

- ^ Mahajan (2007). History of Medieval India. S. Chand. p. 75. ISBN 9788121903646.

- ^ Chandra, Satish (2007). History of Medieval India:800–1700. Orient Longman. p. 73. ISBN 978-81-250-3226-7. Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

He resorted to large-scale slaughter of the Khokhars and cowed them down. On his way back to Ghazni, he was killed by a Muslim fanatic belonging to a rival sect

- ^ C. E. Bosworth (1968), The Political and Dynastic History of the Iranian World (A.D. 1000–1217), Cambridge University Press, p. 168, ISBN 978-0-521-06936-6, archived from the original on 29 January 2021, retrieved 27 September 2022,

The suppression of revolot in the Punjab occupied Mu'izz al-Din's closing months, for on the way back to Ghaza he was assassinated, allegedly by emissaries of the Isma'ils whom he had often persecuted during his life time (602/1206)

- ^ Habib 1981, p. 153–154.

- ^ "Patna University Journal, Volume 18". Patna University Journal. 18: 98. 1963.

...implying that some of the accomplices were non-Muslims, probably Gakkhar or Khokhar and is, therefore, of opinion that the deed was a joint Qārāmitah (Bātini) Khokar or Gakkhar affair.

- ^ Āg̲h̲ā Mahdī Ḥusain (1967). Futūhuʼs Salāt̤īn:Volume 1. p. 181.

It is also said that the assassinators were Khokhars, for the Khokhars too might be called Mulahid or Malahida.

- ^ Abdul Mabud Khan, Nagendra Kr Singh (2001). Encyclopaedia of the World Muslims:Tribes, Castes and Communities · Volume 2. Global Vision. p. 438. ISBN 9788187746058.

malahida and fida'is (i.e., agents of the Alamut Isma'ilis), which is somewhat curious in view of the recent conversion of the Gakkhars to Islam.

- ^ a b Wink 1991, p. 238.

- ^ Habib 1981, p. 133-134.

- ^ Syed (2004), p. 52

- ^ Basham & Rizvi (1987), p. 30

- ^ Chandra (2004), p. 66

- ^ Jackson (2003), p. 268

- ^ Surinder Singh (2019). The Making of Medieval Panjab: Politics, Society and Culture C. 1000–c. 1500. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000760682.

- ^ Proceedings - Punjab History Conference. Vol. 13. Department of Punjab Historical Studies, Punjabi University. 1980. p. 74. ISBN 9788173804601 – via University of Virginia.

- ^ Asit Kumar Sen (1963). People and Politics in Early Mediaeval India (1206-1398 A.D.). Indian Book Distributing Company. p. 92 – via the University of Michigan.

- ^ Irfan Habib, Najaf Haider (2011). Economic History of Medieval India, 1200-1500. Pearson Education India. p. 119. ISBN 9788131727911.

exclaimed anxiety about his family and his dependents' journey from Ajodhan (Pakpattan) to Multan, since an uprising of the Khokhars had made the road unsafe.

- ^ Agha Hussain Hamadani (1992). The Frontier Policy of the Delhi Sultans. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors (P) Limited.

- ^ Ayyappa Panikkar, K. Ayyappa Paniker (1997). Medieval Indian Literature: Surveys and selections. Sahitya Akademi. p. 72. ISBN 9788126003655.

- ^ John F. Richards; David Gilmartin; Munis D. Faruqui; Richard M. Eaton; Sunil Kuma (7 March 2013). Expanding Frontiers in South Asian and World History: Essays in Honour of John F. Richards. Cambridge University Press. p. 247. ISBN 9781107034280.

Mallu Khan (also known as Iqbal Khan), a former slave

- ^ Saran, Richard; Ziegler, Norman P. (19 January 2021). The Mertiyo Rathors of Merto, Rajasthan: Select Translations Bearing on the History of a Rajput Family, 1462–1660, Volumes 1–2. University of Michigan Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-472-03821-3.

- ^ Kothiyal, Tanuja (14 March 2016). Nomadic Narratives: A History of Mobility and Identity in the Great Indian Desert. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-107-08031-7.

- ^ Richard M. Eaton (2019). India in the Persianate Age: 1000–1765. University of California Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0520325128.

The career of Khizr Khan, a Punjabi chieftain belonging to the Khokar clan...

- ^ Orsini, Francesca (2015). After Timur left : culture and circulation in fifteenth-century North India. Oxford Univ. Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-19-945066-4. OCLC 913785752. Archived from the original on 18 November 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ Pandey (1970), p. 223

- ^ Singh (1972), pp. 220–221

- ^ Yong (2005), p. 74

Bibliography

- Basham, Arthur Llewellyn; Rizvi, Saiyid Athar Abbas (1987) [1954], The Wonder that was India, vol. 2, London: Sidgwick & Jackson, ISBN 978-0-283-99458-6

- Chandra, Satish (2004), From Sultanat to the Mughals-Delhi Sultanat (1206-1526), Har-Anand Publications, ISBN 9788124110645

- Habib, Mohammad (1981). Politics and Society During the Early Medieval Period: Collected Works of Professor Mohammad Habib. People's Publishing House.

- Jackson, Peter (2003), The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521543293, retrieved 18 August 2021

- Pandey, Awadh Bihari (1970), Early medieval India (Third ed.), Central Book Depot

- Singh, Fauja (1972), History of the Punjab, vol. III, Patiala

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Syed, M. H. (2004), History of Delhi Sultanate, New Delhi: Anmol Publications, ISBN 978-81-261-1830-4

- Yong, Tan Tai (2005), The Garrison State: The Military, Government and Society in Colonial Punjab, 1849-1947, Sage Publications India, p. 74, ISBN 9780761933366