László Mednyánszky

László Mednyánszky | |

|---|---|

László Mednyánszky | |

| Born | Ladislaus Josephus Balthasar Eustachius Mednyánszky 23 April 1852 Beckó (Beckov), Austrian-Hungarian kingdom (present-day Slovakia) |

| Died | 17 April 1919 (aged 66) |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Known for | Painter |

| Movement | Impressionism |

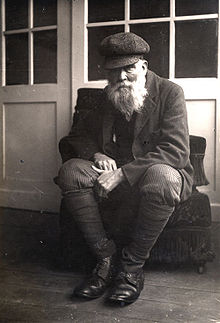

Baron László Mednyánszky,[1] also known by his Latinized name Ladislaus Josephus Balthasar Eustachius Mednyánszky (Slovak: Ladislav Medňanský; 23 April 1852 – 17 April 1919), was a Hungarian-Slovak

painter and philosopher, considered one of the most enigmatic figures in the history of Slovakian and Hungarian art.[2][3][4][5] Despite an aristocratic background, he spent most of his life moving around Europe working as an artist. Mednyánszky spent considerable periods in seclusion but mingled with people across society – in the aristocracy, art world, peasantry and army – many of whom became the subjects of his paintings. His most important works depict scenes of nature and poor, working people, particularly from his home region in Slovakia Kingdom of Hungary. He is also known as a painter of scenes from Upper Hungarian/Slovakian folklore.[6]

Biography[edit]

Mednyánszky was born in Beckó, Kingdom of Hungary, Austrian Empire (present-day Beckov, Slovakia), to Eduárd Mednyánszky and Mária Anna Mednyánszky (née Szirmay), both of whom came from landowning families. He came from a Hungarian noble[7] family. Some say he was of Slovak origin;[8] However, according to others, he was born into a Hungarian family with Polish[9][10] and Hungarian[11] ancestry. One of his grandmothers, Eleonora Richer, was of French origin.[9] His native language was Hungarian and it is not known whether he could speak Slovak.[11]

Mednyánszky's family moved in 1861 to the chateau of his grandfather, Baltazár Szirmay, at Nagyőr (Strážky), near Szepesbéla (Spišská Belá, now in northeastern Slovakia). This was to be the setting for many of his works. Mednyánszky met the Austrian artist Thomas Ender in 1863 when Ender visited the chateau. Ender took an interest in Mednyánszky's early efforts at drawing, lending his assistance to improve Mednyánszky's skills.

Mednyánszky attended a grammar school in Késmárk (Kežmarok), near his home, then attended the Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Academy of Fine Arts) in Munich in 1872–1873. Dissatisfied in Munich, he moved to Paris[3] to attend the École des Beaux-Arts. After the death of his professor, Isidore Pils, in 1875, Mednyánszky left the École and began practicing independently from Montmartre.

Mednyánszky returned to Nagyőr (Strážky) after 1877 to continue painting, and subsequently traveled widely across Europe, between his childhood homes in Upper Hungary and Budapest, Vienna, Paris and beyond. Mednyánszky visited the Szolnok artists' colony in the autumn of 1877 and Italy in 1878. His mother died in 1883, after which he lived in seclusion in Nagyőr. He returned to Nagyőr in 1887 to help deal with an outbreak of cholera, but soon fell ill himself with pneumonia. He spent much of 1889–1892 in Paris and returned regularly to Nagyőr (Strážky) until 1900. His father, Eduard, died in 1895. Mednyánszky held his only solo exhibition at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris in 1897. From the years 1905–1911 he lived in Budapest, then later moved to Vienna.

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Mednyánszky was in Budapest again. He worked as a war correspondent on the Austro-Hungarian frontlines in Galicia, Serbia, and the southern Tirol. In the spring of 1918, he returned to Nagyőr (Strážky) to recover from war wounds. After spending some time working in Budapest, Mednyánszky died in poor health in the spring of 1919, in Vienna. He was homosexual, having had several relationships with men throughout his life. The longest and most important one, with Bálint Kurdi of Vác, lasted for decades.[12]

Political views[edit]

He tried to establish an association against the Pan-Slav agitators with the Hungarian politician Béla Grünwald.[13] Grünwald banned Matica Slovenska.[11] The articles of association of this organization were written by Mednyánszky.[11] This association had a few thousand members.[11]

Works[edit]

Mednyánszky's works were largely in the Impressionist tradition, with influences from Symbolism and Art Nouveau. His works depict landscape scenes of nature, the weather and everyday, poor people such as peasants and workmen. The region of his birth, the northeastern part of the Kingdom of Hungary, part of Austria-Hungary, was the site and subject of many of his paintings; scenes from the Carpathian Mountains and the Hungarian Plains are numerous. He also painted portraits of his friends and family, and images of soldiers during the First World War[14] whilst working as a war correspondent.

His works are currently displayed in the Slovak National Gallery in Bratislava and Strážky chateau, which was donated to SNG by his niece Margit Czóbel in 1972.[15] Many of his works are displayed in the Hungarian National Gallery[4] in Budapest[14] as well. A large number of his works were destroyed during the Second World War.

In 2004 a New York gallery was host to a show of about seventy 19th- and early 20th-century Hungarian paintings, and a few works on paper, from the collection of Nicholas Salgo, a former United States ambassador to Hungary.[5] The exhibition's title, Everywhere a Foreigner and Yet Nowhere a Stranger, was drawn from Mednyánszky's diary.[5]

List of works[edit]

- Marshland (1880)

(Oil on canvas, 28 × 42 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Night Travellers at a Cross (Nocni Putnici pri Krizi, 1880)

(Tempera on panel, 244 cm × 94.5 cm, Slovak National Gallery, Bratislava)

- Osiery with Cows (c. 1880)

(Oil on canvas, 40 × 60 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Watering (c. 1880)

(Oil on canvas, 114 × 201 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Fishing on the Tisza (after 1880)

(Oil on canvas, 153.5 × 49 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Waterside Scene in Luminescent Haze

(Oil on canvas, 29.5 × 48 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Waterside Scene with Figure

(Oil on canvas, 85.5 × 99 cm, Private collection)

- Old Tramp (1880s)

(Oil on wood, 17.5 x 13 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Head of a Boy (c. 1890)

(Oil on wood, 41 × 31 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Angler (1890)

(Oil on wood, 27 × 21 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- View of the Forest (1890–91)

(Oil on wood, 32.5 × 22,5 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Trees with Hoar-frost (c. 1892)

(Oil on canvas, 36.5 × 29 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Under the Cross (c. 1892)

(Oil on canvas, 34 × 50 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Landscape at Autumn (1890s)

(Oil on canvas, 101 × 74 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- In the Garden

(Oil on canvas, 60 × 90 cm, Janus Pannonius Museum, Pécs)

- Peasant Lad

(Oil on canvas, 55 × 45 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Study of a Head (Nyuli)

(Oil on canvas, 47 × 32 cm, Private collection)

- View of Dunajec (1890–95)

(Oil on canvas, 98 × 73 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- 'Iron Gate at the Danube (1890–95)

(Oil on canvas, 120 × 195 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Mountain Landscape with Lake

(Oil on canvas, 80 × 100 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Lake in the Mountains (1895–99)

(Oil on canvas, 33 × 41,5 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Thawing of Snow (1896–99)

(Oil on canvas, 120 × 140 cm, Dobó István Castle Museum, Eger)

- Head of a Tramp (c. 1896)

(Oil on wood, 45 × 34.5 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Absinth Drinker (c. 1898)

(Oil on canvas, 35 × 26.5 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Down-and-out (after 1898)

(Oil on canvas, 120 × 140 cm, Private collection)

- Houses by the River (after 1898)

(Oil on canvas, 40.5 × 61 cm, Private collection)

- Waterside House

(Oil on canvas, 72.5 × 100 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Old Man (1896–97)

(Oil on canvas, 100 × 70,5 cm, Private collection)

- Tramp Seated on a Bench (c. 1898)

(Oil on canvas, 70 × 100 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Man Seated Wearing Hat

(Oil on canvas, 34 × 26 cm, Private collection)

- After the Brawl (c. 1898)

(Oil on canvas, 85 × 65 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- In the Tavern (after 1898)

(Oil on canvas, 162 × 130 cm, Private collection)

- Landscape in the Alps (View from the Rax) (c. 1900)

(Oil on canvas, 28,3 × 34.5 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Tramp with Cigar (c. 1900)

(Oil on canvas, 28.5 × 23 cm, Hungarian National Gallery, Budapest)

- Head of a Tramp with Light Hat (c. 1900)

(Oil on cardboard, 36.5 × 28 cm, Private collection)

- Winter (1906)

(Oil on wood, 25 × 30.5 cm, Private collection)

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2008) |

Gallery[edit]

-

Soldiers (c.1914-18)

-

Prisoners Marching Off 1914-18 (1914–18)

-

Hillside in Springtime (1903–04)

-

Shylock, ca. 1900

-

Iron Gates on the Danube (1890–95)

-

Angling Boy, (1890)

-

Landscape in Autumn (ca 1890)

-

Old Tramp (c.1880)

-

Watering (1852-1919)

-

Day Labourer

References[edit]

- ^ Cornis-Pope, Marcel; Neubauer, John (2004). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and Disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 173. ISBN 90-272-3453-1.

- ^ Németh, Lajos (1969). Modern art in Hungary. Corvina Press. ISBN 9780800217228. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ a b Simon, Andrew L. (1998). Made in Hungary: Hungarian Contributions to Universal Culture. Simon Publications LLC. p. 57. ISBN 0-9665734-2-0.

- ^ a b Simons, Mary (2 October 1988). "Budapest As a City of Museums". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- ^ a b c Genocchio, Benjamin (11 January 2004). "ART REVIEW; Foreigners in Strange Lands, But at Home in the World". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- ^ "Múzeum Slovenského vizuálneho umenia. 2011". Muzeum.artgallery.sk. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ Hárs, Éva; Romváry, Ferenc (1981). Modern Hungarian Gallery, Pécs. Corvina Kiadó. p. 42. ISBN 978-963-13-1401-4.

- ^ Society for the History of Czechoslovak Jews (1971). Dr. Kurt – Chairman WEHLE. 1971. Jewish Publication Society of America. ISBN 9780827602304. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ^ a b Gyula Duba, Mednyánszky, Irodalmi Szemle, 2004/10, Translations: "lengyel ősről és a „stiborida" rokonságról-Polish ancestry and 'Stiborida relations'; "Franciaföldről hozta a szép Richer Eleonórát-He (his grandfather) brought his wife from France"

- ^ Nyitra vármegye nemesi családai (Noble families of Nyitra county) from: Samu Borovszky, Magyarország vármegyéi és városai. Nyitra vármegye (Counties and towns of Hungary, Nyitra county), 1899, Translation: "(Mednyánszky) családi hagyomány szerint Lengyelországból származott – They were originated from Poland according to the traditions of Mednyánszky family"

- ^ a b c d e Csilla Markója, Verekedés után, Mednyánszky a Budapest – Pozsony – Bécs háromszögben Archived 28 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Európai utas Review Archived 11 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 2004, pp. 22–23 Translations: "Mednyánszky nem csupán magyar családban magyar anyanyelvűként született, és nem is biztos, hogy tudott szlovákul- Mednyánszky was born into a Hungarian family with native Hungarian tongue and it is not even sure that he could speak in Slovak"; "(Grünwald)... betiltotta az 1863-ban alakult Matica Slovenskát-Grünwald banned Matica Slovenska, which was established in 1863"; "A pánszláv mozgalmak ellen életre hívott egylet alapító okiratának Mednyánszky tollából származó tervezete-The association was created against the Pan-Slav movement and the articles of association of this organization were written by Mednyánszky"; ".. pár ezer tagja lett- had a few thousands members"

- ^ "Po smrti mu nesplnili najväčšiu túžbu, ležať vedľa jeho životnej lásky".

- ^ Szalatnai, Rezső (1969). Arcképek, háttérben hegyekkel: esszék és emlékezések. Szépirodalmi Könyvkiadó. p. 213.

- ^ a b "Hungarian National Gallery". Lonely Planet.

- ^ "Slovenska narodna galeria. 2011". Muzeum.sk. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

External links[edit]

- Fine Arts in Hungary: Works by László Mednyánszky

- SNG online at www.sng.sk – Slovakian National Gallery Online: Ladislav Mednyánszky and Strážky

- Works held in Slovak art collections

- 1852 births

- 1919 deaths

- People from Nové Mesto nad Váhom District

- Academy of Fine Arts, Munich alumni

- Burials at Kerepesi Cemetery

- 19th-century Hungarian painters

- 20th-century Hungarian painters

- Hungarian male painters

- 19th-century Hungarian male artists

- 20th-century Hungarian male artists

- Gay painters

- Hungarian gay artists

- Hungarian LGBT painters

- Slovak LGBT painters

- 19th-century Slovak painters

- Painters from Austria-Hungary