Hubert Lyautey

Hubert Lyautey | |

|---|---|

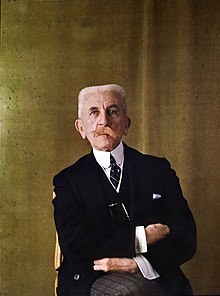

Marshal Lyautey, May 1927 | |

| 114th Minister of War | |

| In office 12 December 1916 – 15 March 1917 | |

| President | Raymond Poincaré |

| Prime Minister | Aristide Briand |

| Preceded by | Pierre Roques |

| Succeeded by | Paul Painlevé |

| 1st Resident-General of France in Morocco | |

| In office 4 August 1907 – 25 August 1925 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Théodore Steeg |

| Seat 14 of the Académie française | |

| In office 31 October 1912 – 27 July 1934 | |

| Preceded by | Henry Houssaye |

| Succeeded by | Louis Franchet d'Espèrey |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 17 November 1854 Nancy, French Empire |

| Died | 27 July 1934 (aged 79) Thorey, French Republic |

| Resting place | Les Invalides |

| Nationality | French |

| Spouse | Inès de Bourgoing |

| Parents |

|

| Alma mater | École Spéciale Militaire |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | French Army |

| Years of service | 1873–1925 |

| Rank | Marshal[a] |

| Battles/wars | Black Flags Rebellion

French Conquest of Morocco First World War Zaian War |

Louis Hubert Gonzalve Lyautey[b] (17 November 1854[1] – 27 July 1934) was a French Army general and colonial administrator.

After serving in Indochina and Madagascar, he became the first French Resident-General in Morocco from 1912 to 1925. In early 1917, he served briefly as Minister of War. From 1921, he was a Marshal of France.[2] He was dubbed the French empire builder and in 1931 made the cover of Time.[3][4] Lyautey was also the first one to use the term "hearts and minds" as part of his strategy to counter the Black Flags rebellion during the Tonkin campaign in 1885.[5]

Early life

[edit]Lyautey was born in Nancy, the capital of Lorraine. His father was a prosperous engineer and his grandfather a highly-decorated Napoleonic general. His mother was a Norman aristocrat, and Lyautey inherited many of her assumptions: monarchism, patriotism, Catholicism and the belief in the moral and political importance of the elite.[6] He attended lycée in Dijon, where he recalled he was fascinated with René Descartes' Discours de la Methode.[7]: 177

In 1873, he entered the French military academy of Saint-Cyr. He attended the army training school in early 1876 and in December 1877 was made a lieutenant. After graduating from Saint-Cyr, two months of holiday in Algeria in 1878 left him impressed by the Maghreb and by Islam.[6] He served in the cavalry[8] and was to make his career serving in the colonies, not in a more prestigious assignment in metropolitan France. In 1880, he was posted to Algiers and then campaigned in southern Algeria. In 1884, to his disappointment, he was recalled to France.[9]

Military career

[edit]Indochina

[edit]In 1894, he was posted to Indochina, serving under Joseph Gallieni. He helped crush the so-called piracy of the Black Flags rebellion along the Chinese border. He then set up the colonial administration in Tonkin and then became head of the military office of the Government-General in Indochina. When he left Indochina in 1897, he was a lieutenant colonel and had received the Legion of Honour.[10]

In Indochina, he wrote:

Here I am like a fish in water, because the manipulation of things and men is power, everything I love.[11]

Madagascar

[edit]From 1897 to 1902, Lyautey served in Madagascar, again under Gallieni. He pacified northern and western Madagascar; administered a region of 200,000 inhabitants; began the construction of a new provincial capital at Ankazobe and a new roadway across the island; He encouraged the cultivation of rice, coffee, tobacco, grain, and cotton; and opened schools. In 1900 he became Governor of Southern Madagascar, an area a third the size of France with a million inhabitants; 80 officers and 4,000 soldiers served under him.[9] He was also promoted to colonel in 1900. In Madagascar. he wrote to his father:

He believed that he did not crave power for its own sake.[11] He returned to France to command a cavalry regiment in 1902 before he was promoted to brigade general a year later, largely a result of the military skill and success which he had shown in Madagascar.[8]

Morocco

[edit]

In 1903, he was posted to command first a subdivision south of Oran and then the whole Oran district, his official task being to protect a new railway line against attacks from Morocco.[12][13][page needed] French commanders in Algeria moved into Morocco largely on their own initiative in early 1903. Later that year, Lyautey marched west and occupied Béchar, a clear breach of the 1840s treaties. The following year, he advanced further into Morocco in clear disobedience of the Minister of War and threatened to resign if he were not supported by Paris. The French Foreign Minister issued a vague disavowal of Lyautey because he was concerned at clashing with British influence in Morocco.[14] In the event, Britain, Spain and Italy were placated by France agreeing to allow them a free hand in Egypt, northern Morocco, and Libya respectively, and the only objections to French expansion in the region came from Germany (see First Moroccan Crisis).[15]

Lyautey met Isabelle Eberhardt in 1903 and employed her for intelligence missions. After her death in 1904, he chose her tombstone.[16]

In early 1907 Émile Mauchamp, a French doctor, was killed in Marrakesh, possibly as he was attempting to lay the groundwork for French expansion. Lyautey then occupied Oujda in eastern Morocco near the Algerian border.[17] Having been promoted to division general, Lyautey was the military governor of French Morocco from 4 August 1907. After taking Oudja, he went to Rabat to put pressure on the Sultan and got embroiled in a power struggle between the Sultan and his brother, with Germany and France taking sides in the dispute.[12]

On 14 October 1909 in Paris, Lyautey married Inès Fortoul, née de Bourgoing, god daughter of former Empress Eugénie and president of the French Red Cross, who had just organized the Red Cross in Morocco. The marriage was childless.[18] He returned to France in 1910, and in January 1911, he took up command of a corps at Rennes.[8][12]

In 1912 Lyautey was posted back to Morocco and relieved Fez, which was being besieged by 20,000 Moroccans. After the Convention of Fez established a protectorate over Morocco, Lyautey served as Resident-General of French Morocco from 28 April 1912 to 25 August 1925. Sultan Moulay Hafid abdicated at the end of 1912, replaced by his more pliable brother, although the country was not fully pacified until 1934.[19]

On 31 October 1912, he was elected at the seat 14 of the Académie française.[20]

First World War

[edit]On 27 July 1914, Resident-General Lyautey received a cable from Paris from the undersecretary of foreign affairs Abel Ferry.[21] He was quoted as telling his officers:

They are completely mad. A war between Europeans is a civil war. This is the most monumental foolishness that they have ever done.[22]

However, like many professional soldiers, he disliked the Third Republic and in some ways welcomed the outbreak of war "because the politicians have shut up".[23] The same day, War Minister Messimy told Lyautey to prepare to abandon Morocco except for the major cities and ports and to send all seasoned troops to France. Messimy later said that had been a "formal" order.[24]

At the outbreak of the war, Lyautey commandied 70,000 troops, all members of the Armée d'Afrique or part of La Coloniale. Under French law, metropolitan conscripts could not serve except under very exceptional circumstances abroad. Initially, he sent two Algerian-Tunisian divisions to the western front, then another two, plus two brigades of Algerians serving in Morocco, and a brigade of 5,000 Moroccans. Over 70 battalions of Algerians and Tunisians served on the Western Front, and one Moroccan and seven Algerian regiments of Spahis (cavalry) served dismounted on the Western Front. Others fought in Macedonia or mounted in the Levant.[25]

In 1914, 33 officers, 580 soldiers and the weapons of two battalions were lost in an expedition near Khenifra. Although that was to prove the only incident in Morocco during the war, Lyautey was worried about the threat of jihad as a result of German propaganda in Morocco, and many of the remaining legionnaires were German. Four territorial regiments were sent from southern France and served alongside the mobilised European colonists.[26] By mid-1915 Lyautey had sent 42 battalions to the Western Front, receiving in return middle-aged reservists (who to his delight were regarded as seasoned warriors by the Moroccans), battalions of Tirailleurs sénégalais and Tirailleurs marocains, as well as irregular Moroccan goumiers. With 200,000 men, Lyautey had to hold down the Middle Atlas and the Rif and to suppress rebellions by Zaians at Khenifra, Abd al Malik at the Taza, and al Hiba in the south, the latter aided by German U-boats. Lyautey argued that Verdun and Morocco were part of the same war.[27]

Lyautey disregarded advice to concentrate major forces in a few cities and took a personal risk by spreading them all over the country. In the end, his gamble turned right as he got a psychological edge over potentially mutinous tribal chiefs.[21] Lyautey had 71,000 men by July 1915. He insisted France would win the war and continued with the usual trade fairs and road and rail construction.[26]

Political career

[edit]Colonial policies

[edit]His personal beliefs evolved from monarchism and conservatism to a belief in social duty. He wrote a journal article "On the Social Function of the Officer under Universal Military Service". However, his colonial policies were similar in practice to those of Gallieni, a secular republican.[8] He was suspicious of republicanism and socialism, and believed in the social role of the Army in regenerating France.[11]

Lyautey adopted and emulated Gallieni's policy of methodical expansion of pacified areas followed by social and economical development (markets, schools and medical centres) to bring about the end of resistance and the cooperation of former insurgents. This method became known as tache d'huile (literally "oil stain"), as it resembles oil spots spreading to cover the whole surface. Lyautey's writings have had a significant influence on contemporary counterinsurgency theory through its adoption by David Galula.[28] He also practiced a policy known as politique des races of dealing separately with each tribe to avoid any tribe from gaining too much influence within the colonial system.[29]

Lyautey is considered to have been an apt colonial administrator. His governing style evolved into the Lyautey system of colonial rule. The Lyautey system invested in pre-established local governing bodies and advocated for local control. He advocated for finding a sub-group that had nationalistic tendencies but had a strong desire for local autonomy and then investing in the sub-group as political leaders.[30] He tried to balance blunt military force with other means of power and promoted a vision of a better future for the Moroccans under the French colonial administration. For example, he invited a talented young French urban planner, Henri Prost, to design comprehensive plans for redevelopment of the major Moroccan cities.[31][32]

In Morocco from 1912, he was publicly deferential to the sultan[12] and told his men not to treat the Moroccans as a conquered people.[8] He opposed proselytising of Christianity and the settlement of French migrants in Morocco,[33] and quoted with approval Governor Lanessan of Indo-China "we must govern with the mandarin and not against the mandarin".[11]

Minister of War

[edit]Lyautey briefly served as France's Minister of War for three months in 1917, which were clouded by the unsuccessful Nivelle Offensive and the French Army Mutinies. Lyautey was apparently surprised to receive a telegram offering him the job (10 December 1916) and demanded and was given authority to issue orders to Nivelle (the new Commander-in-Chief of French forces on the Western Front) and Sarrail (Commander-in-Chief at Salonika); Nivelle's predecessor Joffre had enjoyed much greater freedom from the War Minister and had also had command over Salonika. Prime Minister Aristide Briand, not going into detail about Joffre's removal, replied that Lyautey would be one of a War Committee of five members, controlling manufacturing, transport and supply, and thus giving him greater powers than his predecessors. Lyautey replied "I shall answer your call". Lyautey had to spend a good deal of time touring units and learning about the Western front.[34][35]

Lyautey was strongly disliked by the political left, and when Briand reconstructed his government in December 1916, Painlevé declined to stay part (he had been Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts) as he was reluctant to be associated with him, although doubts about the replacement of Joffre by Nivelle rather than Philippe Petain also played a role (Painlevé was later himself Minister of War for much of 1917, then briefly Prime Minister late in the year).[36]

Lyautey was met with a fait accompli as Nivelle, whom he would not have chosen, had been appointed Commander-in-Chief by the acting War Minister Admiral Lacaze, whilst munitions under Albert Thomas (formerly Under-Secretary for War) were hived off into a separate ministry assisted by the industrialist Louis Loucheur as Under-Secretary of State. Lyautey had hoped to rely on Joffre, Ferdinand Foch and de Castelnau, but the first soon resigned from his job as advisor, Foch had already been sacked as commander of Army Group North, de Castelnau was sent on a mission to Russia, and Lyautey was not permitted to revive the post of Chief of the Army General Staff.[37]

Lyautey was hard of hearing and inclined to dominate conversation. As minister and cabinet member, he preferred to deal directly with the British government via the British Embassy, to the annoyance of the British CIGS Robertson (at a time when generals of both countries tried to prevent politicians from "interfering" in the details of strategy), who disliked Lyautey. On the train to the Rome Conference (5–6 January 1917) Lyautey stood before a map lecturing the British delegation on their Palestine campaign. Robertson, a man of notorious bluntness, listened to the lecture then asked Lloyd George "has he finished?" before retiring to bed.[35] Robertson told Lloyd George "that fellow won’t last long". He wrote to the King’s adviser Clive Wigram (12 January):

Lyautey … is a dried up person of the Anglo-Indian type who has been in the colonies all his life and talks of nothing else. He talks a good deal. He has no grasp whatever of the war as yet and I should doubt if he remains long where he is now.[38]

Lyautey attended the infamous Calais Conference on 27 February 1917, at which Lloyd George attempted to subordinate British forces in France to Nivelle. After a serious argument had broken out between Lloyd George and the British generals, Lyautey claimed that he had not seen the proposals until he boarded the train for Calais.[39] On being shown Nivelle's plan, Lyautey declared that it was "a plan for "the Duchess of Gerolstein" " (a light opera satirising the army). He contemplated trying to have Nivelle dismissed but backed down in the face of traditional republican hostility to military men with political aspirations.[40][41] Lyautey shared his concerns about Nivelle with Petain, commander of Army Group Centre, who would eventually replace him.[42]

Lyautey refused to discuss military aviation even at a closed session of the French Chamber and at the subsequent open session declared that to discuss such matters even in closed session would be a security risk. He resigned as Minister of War after being shouted down in the Chamber on 15 March 1917, and after several leading politicians declined the post of Minister of War, Aristide Briand's sixth cabinet (12 December 1916 – 20 March 1917) fell four days later.[43][44][45]

Postwar

[edit]

Lyautey caused the Institute for Advanced Moroccan Studies and the Sherifian Scientific Institute to be set up in the early 1920s.[46]

During the First World War, he had insisted on the continuation of the occupation of the whole country regardless of the fact that France needed most of her resources in the struggle against the Central Powers. He was in overall command of French forces during the time of the Zaian War of 1914–21. He resigned in 1925, feeling slighted that Paris had appointed Philippe Pétain to command 100,000 men to put down Abd-el-Krim’s rebellion in the Rif Mountains.[12]

Political opposition in Paris ensured that he received no official recognition when he resigned; his only escort home was two destroyers of the Royal Navy.[8]

Marshal Lyautey served as honorary president of the three French Scouting associations.[47]

Paris Exposition

[edit]Lyautey was commissioner of the Paris Colonial Exposition of 1931, designed to encourage support for the empire in Metropolitan France. The introduction to the visitors guide contained Lyautey’s instruction: "you must find in this exhibition, along with the lessons of the past, the lessons of the present and above all lessons for the future. You must leave the exhibition resolved always to do better, grander, broader and more versatile feats for Greater France." A special extension line of the Paris Metro was built to Bois de Vincennes. Despite costing the French government and City of Paris 318m francs, the exhibition made a profit of 33m francs. Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, Italy, Portugal and the USA also contributed exhibitions on their overseas possessions, but not Britain, which despite repeated pleas by Lyautey cited the cost of its own exhibition of 1924.[48]

The Palais de la Porte Dorée in Bois de Vincennes housed part of the Colonial Exhibition of 1931; Lyautey's study is preserved as part of the foyer.[49]

Final years

[edit]

In his final years, Lyautey became associated with France's growing fascist movement. He admired Italian leader Benito Mussolini, and was associated with the far right Croix de Feu. In 1934, he threatened to lead the Jeunesses Patriotes to overthrow the government.[50] The same year he contributed to the effort to warn French people against Hitler through a critical introduction of an unauthorised edition of Mein Kampf.

Lyautey would have liked to have been a national saviour; he was disappointed to have played only a minor role in France's political life and in the First World War.[51]

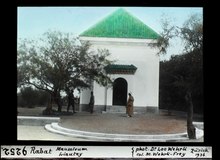

Lyautey died in Thorey-Lyautey in 1934. His ashes were brought back to Morocco, where they lay in state in a mausoleum in the Chellah, at Rabat. After Morocco became independent in 1956, his remains were returned to France and interred in Les Invalides in 1961.[52][12]

Homosexuality

[edit]Lyautey has been called "perhaps France's most distinguished – or infamous – homosexual."[53] Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau – whom Lyautey despised, as he did most politicians – is quoted as having said:

Here is an admirable and courageous man who always had balls up to his ass. It's just a shame that they are not always his.[54]

It has been speculated that Lyautey might have provided Marcel Proust with the model for the character of the homosexual Baron de Charlus in his magnum opus Remembrance of Things Past.[53]

The actual evidence for Lyautey being a homosexual is primarily circumstantial,[55] but it was widely regarded as an open secret at the time,[54][56] one which some historians claim Lyautey did not take any effort to hide.[57][58] Robert Aldrich writes that he liked hot climates and "the masculine company of young officers".[11] Lyautey's wife is said to have told a group of her husband's young officers that "I have the pleasure of informing you that last night I made you all cuckolds," implying that the officers were all paramours of her husband, and that she had had sex with Lyautey the night before.[54]

Lyautey's homosexuality, or at the very least his "homophile sensuality"[58] or "Greek virtues",[54] was in some ways connected with his time in Morocco. Lyautey's sexual preference for men was not caused by his sojourn in Morocco, as there were those who objected to his appointment as commander there because he was a homosexual.[57]

In popular culture

[edit]Lyautey plays a major role in Garment of Shadows (2013), a Sherlock Holmes/Mary Russell novel by Laurie R. King, set in Morocco in 1925. He is said to be a distant cousin of Holmes.

Military ranks

[edit]| Cadet | Second lieutenant | Lieutenant | Captain | Squadron chief[d] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 October 1873[59] | 25 September 1875[60] | 1 January 1876 | 22 September 1882 | 22 March 1893[61] |

| Lieutenant colonel | Colonel | Brigade general | Division general | Marshal of France |

| 7 September 1897 | 1900 | 9 October 1903[62] | 30 July 1907[63] | 19 February 1921[64] |

Honours and decorations

[edit]

French Honours

[edit] France:

France:

Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour Officer of the Order of Agricultural Merit

Officer of the Order of Agricultural Merit Military Medal[65]

Military Medal[65]

French Morocco:

French Morocco:

Grand Cordon of the Order of Ouissam Alaouite

Grand Cordon of the Order of Ouissam Alaouite Member of Order of Sherifian Military Merit

Member of Order of Sherifian Military Merit Colonial Medal (Morocco Bars)

Colonial Medal (Morocco Bars) Morocco commemorative medal

Morocco commemorative medal

French Protectorate of Cambodia

French Protectorate of Cambodia

Commander of the Royal Order of Cambodia

Commander of the Royal Order of Cambodia

French Annam

French Annam

Commander of the Order of the Dragon of Annam

Commander of the Order of the Dragon of Annam

Anjouan

Anjouan

Commander of the Order of the Star of Anjouan

Commander of the Order of the Star of Anjouan

Foreign Honours

[edit] Belgium:

Belgium:

Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold

Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold

Japan:

Japan:

Officer of the Order of the Rising Sun

Officer of the Order of the Rising Sun

Portugal:

Portugal:

Knight of the Order of Christ

Knight of the Order of Christ

Russian Empire

Russian Empire

Knight of the Order of Saint Stanislaus

Knight of the Order of Saint Stanislaus

Spain

Spain

Knight Grand Cross with collar of the Royal and Distinguished Spanish Order of Charles III

Knight Grand Cross with collar of the Royal and Distinguished Spanish Order of Charles III

Vatican

Vatican

Knight Grand Cross of the Pontifical Equestrian Order of St. Gregory the Great

Knight Grand Cross of the Pontifical Equestrian Order of St. Gregory the Great

Dynastic Orders

[edit] Royal House of Orléans

Royal House of Orléans

Knight of the Order of the Holy Spirit

Knight of the Order of the Holy Spirit

Burial and legacy

[edit]

Following his resignation from the position of Resident-general in 1925, Lyautey planned for his own burial in Rabat and in 1933 requested painter Joseph de La Nézière to produce a sketch for his mausoleum as a traditional Muslim Qubba. Following Lyautey's death in France on 1934-07-27 and his state funeral in Nancy on 1934-08-03, the French authorities decided to locate his resting place on the Protectorate Residence's grounds rather than in more iconic locations such as Chellah or near the Hassan Tower, which could have offended some Muslim Moroccan sensitivities. Even so, the erection of a monument to Morocco's Christian colonizer was controversial and criticized by Mohamed Belhassan Wazzani and other nationalist and Muslim leaders. Reflecting those misgivings, Sultan Mohammed V of Morocco declined to attend the funeral on the Residence grounds on 1935-10-31, when Lyautey's remains were eventually placed in the completed mausoleum, even though he participated in a ceremony earlier the same day at Bab er-Rouah in downtown Rabat. The mausoleum building was designed by architect René Canu based on La Nézière's sketch.[66]

Following Moroccan independence, French President Charles de Gaulle and Mohammed V, by then the King of Morocco, agreed to preempt the risk of incidents around the still controversial mausoleum and to repatriate Lyautey's remains, which were ceremoniously removed on 1961-04-22 and shipped to France via Casablanca.[67] The mausoleum remained empty thereafter.[66] Lyautey was reburied in Les Invalides in Paris, first in the crypte des Gouverneurs of the church of Saint-Louis-des-Invalides on 1961-05-10, and then in 1963 in the complex's Dome Church. There, his remains lie in an ornamented casket designed by Albert Laprade, the Residence's original architect almost a half-century earlier, and made by celebrated art deco metalworker Raymond Subes.[68]

- The town of Kenitra, Morocco was named "Port Lyautey" by the French in 1933, but renamed after independence in 1956.[69]

- The Garrison of the 13th Parachute Dragoon Regiment is named after him.[citation needed]

- Lycée Lyautey in Casablanca, Morocco is named after him.[70] An equestrian statue of Lyautey is located at the French consulate in Casablanca.[71]

- Lyautey is remembered for his words in a critical moment, "Whoever does not impose his will submits to that of the enemy."[3]

- Lyautey has been suggested as the author of the aphorism that "a language is a dialect which owns an army and a navy" (Une langue, c'est un dialecte qui possède une armée et une marine).[72]

- Mount Lyautey in the Canadian Rockies was named for him in 1918.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Government of the French Empire. "Birth certificate of Lyautey, Hubert". culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Teyssier, Arnaud. Lyautey: le ciel et les sables sont grands. Paris: Perrin, 2004.

- ^ a b Bell, John (1 June 1922). "Marshal Lyautey: The man and his work". The Fortnightly Review. pp. 905–914. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ Singer, Barnett (1991). "Lyautey: An Interpretation of the Man and French Imperialism". Journal of Contemporary History. 26: 131–157. doi:10.1177/002200949102600107. S2CID 159504670.

- ^ Douglas Porch, "Bugeaud, Gallieni, Lyautey: The Development of French Colonial Warfare", in Makers of Modern Strategy: From Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age, Peter Paret, ed. Princeton University Press, USA, 1986. p. 394.

- ^ a b Aldrich 1996, p134

- ^ Mitchell, Timothy (2003). "6 The philosophy of the thing". Colonising Egypt (Repr ed.). Berkeley, Calif.: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07568-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Clayton 2003, p216-7

- ^ a b Aldrich 1996, p135

- ^ Aldrich 1996, p63, 135

- ^ a b c d e Aldrich 1996, p137

- ^ a b c d e f Aldrich 1996, p136

- ^ Jr, William A. Hoisington (11 August 1995). Lyautey and the French Conquest of Morocco. Palgrave Macmillan US. ISBN 978-0-312-12529-5.

- ^ This was a few years after the Fashoda Incident, and the Entente Cordiale had not yet existed.

- ^ Aldrich 1996, p32-3

- ^ Aldrich 1996, p158

- ^ Aldrich 1996, p34-5

- ^ Singer, Barnett; Langdon, John W. (2008). Cultured Force: Makers and Defenders of the French Colonial Empire. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-299-19904-3.

- ^ Aldrich 1996, p35

- ^ Académie Française. "Louis-Hubert LYAUTEY". www.academie-francaise.fr. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ a b Dean, William T. (2011). "Strategic Dilemmas of Colonization: France and Morocco during the Great War". Historian. 73 (4): 730–746. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.2011.00304.x. S2CID 145277431.

- ^ Le Révérend, André. Lyautey. Paris: Fayard, 1983. p. 368.

- ^ Herwig 2009, p28

- ^ Doughty 2005, p50

- ^ Clayton 2003, p175

- ^ a b Greenhalgh 2014, pp119-20

- ^ Clayton 2003, p181-2

- ^ Rid, Thomas (2010). "The Nineteenth Century Origins of Counterinsurgency Doctrine". Journal of Strategic Studies. 33 (5): 727–758. doi:10.1080/01402390.2010.498259. S2CID 154508657.

- ^ Aldrich 1996, p106

- ^ Rogan, Eugene L. (2009). The Arabs : a history. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-07100-5. OCLC 316825565.

- ^ Cohen, Jean-Louis. Henri Prost and Casablanca: the art of making successful cities (1912–1940). The New City, (fall 1996), № 3, p. 106-121.

- ^ Wright, Gwendolyn. Tradition in the service of modernity: architecture and urbanism in French colonial policy, 1900–1930. The Journal of Modern History, 59, № 2 (1987): 291–316.

- ^ Aldrich 1996, p136-7

- ^ Doughty 2005, p320-1

- ^ a b Woodward, 1998, p. 86.

- ^ Doughty 2005, p338

- ^ Greenhalgh 2014, pp172-3

- ^ Bonham-Carter 1963, p200 "Anglo-Indian" in this context means a British person who has spent his life abroad in the Empire, not a person of mixed race.

- ^ Doughty 2005, p331-2

- ^ Left-wing hostility to generals with military pretensions was largely caused by memories of General Boulanger and in particular of the Dreyfus affair. Gallieni, one of Lyautey's predecessors, had faced similar hostility, wholly unfounded as he had in fact been attempting to assert ministerial control over the Army.

- ^ Clayton 2003, p125

- ^ Greenhalgh 2014, p184

- ^ "Lyautey Resigns as War Minister; French Official Steps Down Because of Stormy Scene in the Chamber. Uproar Prevents Speech. Cabinet's Foes in Tumult When He Questions Desirability of Discussion". The New York Times. 15 March 1917. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ Woodward, 1998, p. 104.

- ^ Doughty 2005, p336

- ^ Aldrich 1996, p248

- ^ John S. Wilson (1959), Scouting Round the World. First edition, Blandford Press. p. 33

- ^ Aldrich 1996, p260-3

- ^ Aldrich 1996, p324

- ^ Szaluta, Jacques "Marshal Petain's Ambassadorship to Spain: Conspiratorial or Providential Rise toward Power?", French Historical Studies 8:4

- ^ Aldrich 1996, p138

- ^ David S. Woolman - Rebels in the Rif - Abd El Krim and the Rif Rebellion (1968, Stanford University Press), p221

- ^ a b Martin, Brian Joseph (2011) Napoleonic Friendship: Military Fraternity, Intimacy, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-century. UPNE. ISBN 9781584659440, p.9

- ^ a b c d Hussey, Andrew (2014) The French Intifada Granta. ISBN 9781847085948

- ^ Merrick, Jeffrey and Sibalis. Michael (2013). Homosexuality in French History and Culture, Routledge. ISBN 1560232633, p. 208-209

- ^ Gershovich, Moshe (2012) French Military Rule in Morocco: Colonialism and its Consequences Routledge. ISBN 9781136325878 p.91 n.27

- ^ a b Porch, Douglas (2005) The Conquest of Morocco Macmillan. ISBN 9781429998857, pp.84–86

- ^ a b Aldrich, Robert (2008) Colonialism and Homosexuality Routledge. ISBN 9781134644599

- ^ Government of the French Republic (12 October 1873). "Liste des élèves admis à l'école spécial militaire". gallica.bnf.fr (in French). Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (25 September 1875). "Classement de sortie de l'école spécial militaire". gallica.bnf.fr (in French). Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (22 March 1893). "Décret portant promotion dans l'armée active". gallica.bnf.fr (in French). Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (9 October 1903). "Décret portant promotion dans l'armée active". gallica.bnf.fr (in French). Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (31 July 1907). "Décret portant promotion dans l'armée active". gallica.bnf.fr (in French). Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ Government of the French Republic (19 February 1921). "Décret portant nomination de Maréchaux de France". gallica.bnf.fr (in French). Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ Government of the French Republic. "Military Medal certificate". culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ a b Stacy Holden (2017), "An Islamicized Mausoleum for Maréchal Hubert Lyautey" (PDF), Hespéris-Tamuda, LII (2): 151–177

- ^ Roland Benzaken (1 March 2014). "Transfert des cendres de Hubert Lyautey à Rabat". Souvenir et récit d'une enfance à Rabat.

- ^ Marie-Christine Pénin (17 November 2016). "Lyautey Hubert (1854-1934), Eglise du Dôme des Invalides (Paris)". Tombes sépultures dans les cimetières et autres lieux.

- ^ Bentaleb, Rachida (4 November 2013). "Morocco's Kenitra: a City of Contrasts". Morocco World News. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ "Le maréchal Lyautey Archived 2016-08-09 at the Wayback Machine." Lycée Lyautey. 12 June 2006. Retrieved on 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Louis Hubert Gonsalve Lyautey". Equestrian Statues. 6 April 2016.

- ^ La gouvernance linguistique : le Canada en perspective (in French). University of Ottawa Press. 1 January 2004. ISBN 9782760305892. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Marshal of France is a dignity and not a rank.

- ^ French pronunciation: [ybɛʁ ljotɛ]

- ^ i.e. an absolute ruler

- ^ equivalent to major

General references

[edit]- Portions of this article were translated from the French language Wikipedia article fr:Hubert Lyautey.

- Aldrich, Robert (1996). Greater France: A History of French Overseas Expansion. Macmillan, London. ISBN 0-333-56740-4.

- Bonham-Carter, Victor (1963). Soldier True:the Life and Times of Field-Marshal Sir William Robertson. London: Frederick Muller Limited.

- Clayton, Anthony (2003). Paths of Glory. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35949-1.

- Doughty, Robert A. (2005). Pyrrhic Victory. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02726-8.

- Greenhalgh, Elizabeth (2014). The French Army and the First World War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60568-8.

- Herwig, Holger (2009). The Marne. Random House. ISBN 978-0-8129-7829-2.

- Woodward, David R. Field Marshal Sir William Robertson. Westport, Connecticut & London: Praeger, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95422-6

Further reading

[edit]- Cooke, James J. "Insubordination in the French Colonial Army: Lyautey, A Case Study, 1903-1912." Proceedings of the Meeting of the French Colonial Historical Society Vol. 2. 1977. online

- Dean, III, William T. "Strategic Dilemmas of Colonization: France and Morocco during the Great War." Historian 73.4 (2011): 730–746.

- Hoisington, William A. Jr. Lyautey and the French conquest of Morocco. Palgrave, Macmillan, 1995.

- Jeffery, Keith (2006). Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson: A Political Soldier. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820358-2.

- La Porte, Pablo. "Lyautey l’Européen: metropolitan ambitions, imperial designs and French rule in Morocco, 1912–25." French History 30.1 (2016): 99–120.

- Maurois, André. Marshal Lyautey. Paris, Plon, 1931. Translated to English and published in London and New York in 1931.

- Munholland, Kim. "Rival Approaches to Morocco: Delcasse, Lyautey, and the Algerian-Moroccan Border, 1903-1905." French Historical Studies 5.3 (1968): 328–343.

- Singer, Barnett. "Lyautey: an interpretation of the man and French imperialism." Journal of contemporary history 26.1 (1991): 131–157.

External links

[edit]- Newsreel of the British Pathé: inspection of Lyautey during the Moroccan Campaign (1922)

- Biography on firstworldwar.com

- Biography on academie-francaise.fr (in French)

- Encyclopedia of World History: "Lyautey" Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Newspaper clippings about Hubert Lyautey in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1854 births

- 1934 deaths

- École Spéciale Militaire de Saint-Cyr alumni

- Ministers of war of France

- French gay men

- French Army generals of World War I

- Gay military personnel

- Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint-Charles

- Grand Officers of the Legion of Honour

- Marshals of France

- Members of the Académie Française

- Military personnel from Nancy, France

- People of the French Third Republic

- Resident generals of Morocco

- 19th-century French military personnel