Mad Max (film)

This article possibly contains original research. (October 2012) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) |

| Mad Max | |

|---|---|

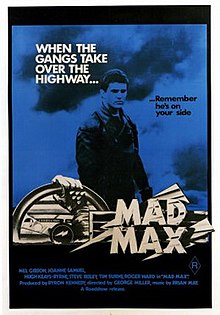

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | George Miller |

| Written by | George Miller Byron Kennedy James McCausland |

| Produced by | Byron Kennedy Bill Miller |

| Starring | Mel Gibson Steve Bisley Joanne Samuel Hugh Keays-Byrne Tim Burns Geoff Parry |

| Cinematography | David Eggby |

| Edited by | Cliff Hayes Tony Paterson |

| Music by | Brian May |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Village Roadshow Pictures (Australia) American International Pictures (United States) Universal Pictures (International) |

Release date | 12 April 1979 |

Running time | 93 minutes |

| Country | Australia |

| Language | English |

| Budget | New evidence suggests around $650,000 (est)[1] |

| Box office | $100,000,000 |

Mad Max is a 1979 Australian science fiction action film directed by George Miller and revised by Miller and Byron Kennedy over the original script by James McCausland, starring Mel Gibson, who had not yet become famous. Its narrative based on the traditional western genre, Mad Max tells a story of breakdown of society, love and revenge. It became a top-grossing Australian film and has been credited for further opening up the global market to Australian New Wave films. It was also the first Australian film to be shot with a widescreen anamorphic lens.[2] The first film in the series, Mad Max spawned sequels Mad Max 2 in 1981 and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome in 1985. A fourth installment, Mad Max: Fury Road starring actor Tom Hardy as Max, is currently in production.

Plot

In a dystopic Australia, after the Earth's oil supplies were nearly exhausted, law and order has begun to break down due to energy shortages. Berserk motorcycle gang member Crawford "Nightrider" Montizano has escaped police custody and is attempting to outrun the Main Force Patrol (MFP) in a stolen Pursuit Special (Holden Monaro). Though he manages to elude his initial pursuers, the MFP's top pursuit man, Max Rockatansky, then engages the less-skilled Nightrider in a high-speed chase, resulting in Nightrider dying in a fiery crash.

Nightrider's motorcycle gang, led by Toecutter and Bubba Zanetti, is running roughshod over a town, vandalising property, stealing fuel and terrorising the populace. Max and officer Jim "Goose" Rains arrest Toecutter's young protégé, Johnny "the Boy" Boyle, when Johnny, too high to ride, stays behind after the gang rapes a young couple. When no witnesses appear for his trial, the courts throw the case out and Johnny is released. An angry Goose attacks Johnny and must be held back; both men shout threats of revenge. After Bubba Zanetti drags Johnny away, MFP Captain Fred "Fifi" McPhee tells his officers to do whatever it takes to apprehend the gangs, "so long as the paperwork's clean."

A short time later, Johnny sabotages Goose's motorcycle; it locks up at high speed, throwing Goose from the bike. Goose is unharmed, though his bike is badly damaged; he borrows a ute to haul his bike back. However, Johnny and Toecutter's gang are waiting in ambush. Johnny throws a brake drum at Goose's windscreen, which shatters and causes Goose to crash the ute; Toecutter then instructs Johnny to throw a match into the gasoline leaking from Goose's wrecked ute, while Goose is trapped inside. Johnny refuses; Toecutter first cajoles, then verbally and physically abuses him. Johnny eventually throws the lit match into the wreckage, which erupts in flames, burning Goose alive.

Goose is rescued, although he dies in the hospital due to his burns. After seeing his charred body, Max becomes disillusioned with the Police Force. Worried of what may happen if he continues working for the MFP – and that he is beginning to enjoy the insanity – Max announces to Fifi that he is resigning from the MFP. Fifi convinces him to take a holiday first before making his final decision about the resignation. Max also reports this to Jessie, his wife at the remote farm where they live, who is happy with his decision so they could take care of their young baby son.

While Max is away to buy supplies, Jessie and her infant encounter Toecutter's gang, who attempt to rape her. She flees, but the gang later finds them again at their remote farm. The gang runs over Jessie and Max's son as they try to escape, leaving their crushed bodies in the middle of the road. Max arrives too late to save them, devastated by the events.

Filled with rage, Max dons his police leathers and takes a supercharged black Pursuit Special (Ford XB Falcon) from the MFP storage to pursue the gang. After torturing a mechanic for information, Max methodically hunts down the gang members: he forces several of them off a bridge at high speed, shoots Bubba at point blank range with his shotgun, and forces Toecutter into the path of a semi-trailer truck. Max finally finds Johnny, who is looting a car crash victim he presumably murdered for a pair of boots. In a cold, suppressed rage, Max handcuffs Johnny's ankle to the wrecked vehicle whilst Johnny begs for his life. Not content to simply kill Johnny right away, Max ignores his begging and sets a crude time-delay fuse with a slow fuel leak and a lighter. Throwing Johnny a hacksaw, Max leaves him the choice of sawing through either the handcuffs (which will take ten minutes) or his ankle (which will take five minutes). Max casually drives away; as he clears the bridge, Johnny's vehicle explodes. Max continues driving into the darkness, with his and Johnny's fate unknown.

Cast

- Mel Gibson as Max Rockatansky

- Joanne Samuel as Jessie Rockatansky

- Hugh Keays-Byrne as Toecutter

- Steve Bisley as Jim "Goose"

- Tim Burns as Johnny the Boy

- Geoff Parry as Bubba Zanetti

- Roger Ward as "Fifi" Macaffee

- David Bracks as Mudguts

- Bertrand Cadart as Clunk

- Stephen Clark as Sarse

- Brendan Heath as Sprog Rockatansky

- Mathew Constantine as Toddler

- Jerry Day as Ziggy

- Howard Eynon as Diabando

- Max Fairchild as Benno

- John Farndale as Grinner

- Sheila Florence as May Swaisey

- Nic Gazzana as Starbuck

- Paul Johnstone as Cundalini

- Vincent Gil as The Nightrider

- Steve Millichamp as "Roop"

- John Ley as "Charlie"

- George Novak as "Scuttle"

- Reg Evans as the station master

- Nico Lathouris as Car mechanic

Development

George Miller was a medical doctor in Victoria, Australia, working in a hospital emergency room, where he saw many injuries and deaths of the types depicted in the film. He also witnessed many car accidents growing up in rural Queensland and had as a teenager lost at least three friends in accidents.[3]

While in residency at a Melbourne hospital, Miller met amateur filmmaker Byron Kennedy at a summer film school in 1971. The duo produced a short film, Violence in the Cinema, Part 1, which was screened at a number of film festivals and won several awards. Eight years later, the duo produced Mad Max, working with first-time screenwriter James McCausland (who appears in the film as the bearded man in an apron in front of the diner).

Miller believed that audiences would find his violent story to be more believable if set in a bleak, dystopic future. Screenplay writer James McCausland drew heavily from his observations of the 1973 oil crisis' effects on Australian motorists:

Yet there were further signs of the desperate measures individuals would take to ensure mobility. A couple of oil strikes that hit many pumps revealed the ferocity with which Australians would defend their right to fill a tank. Long queues formed at the stations with petrol – and anyone who tried to sneak ahead in the queue met raw violence. ... George and I wrote the [Mad Max] script based on the thesis that people would do almost anything to keep vehicles moving and the assumption that nations would not consider the huge costs of providing infrastructure for alternative energy until it was too late.

Finance

Kennedy and Miller first took the film to Graham Burke of Roadshow, who was enthusiastic. The producers felt they would not be able to raise money from the government bodies "because Australian producers were making art films, and the corporations and commissions seemed to endorse them whole-heartedly," according to Kennedy.[5]

They designed a 40 page presentation and it was circulated among a number of different people, and eventually raised the money. Kennedy and Miller contributed funds themselves by doing three months of emergency radio locus work,with Kennedy driving the car while Miller did the doctoring.[5]

Miller claimed the final budget was between $350,000 and $400,000.[6]

Casting

George Miller deliberately wanted to cast lesser known actors so they did not carry past associations with them.[3]

Mel Gibson, a complete unknown at this point, went to auditions with his friend and classmate, Steve Bisley (who would later land the part of Jim Goose). Gibson went to auditions in poor shape, as the night before he had got into a drunken brawl with three men at a party, resulting in a swollen nose, a broken jawline, and various other bruises. Gibson showed up at the audition the next day looking like a "black and blue pumpkin" (his own words). He did not expect to get the role and only went to accompany his friend. However, the casting agent liked the look and told Gibson to come back in two weeks, telling him "we need freaks." When Gibson returned, the filmmakers did not recognise him because his wounds had healed almost completely; he received the part anyway.[7]

Many of the other cast had previously appeared in Stone (1974).

Production

Due to the film's low budget, only Gibson was given a jacket and pants made from real leather. All the other actors playing police officers wore vinyl outfits.

Originally the film was scheduled to take 10 weeks – six weeks of first unit, and four weeks on stunt and chase sequences. However four days into shooting, Rosie Bailey, who was originally cast as Max's wife, was injured in a bike accident. Production was halted for two weeks and Bailey was replaced by Joanne Samuel. This caused a delay of two weeks.

In the end the shoot took six weeks over November and December 1977 with a further six weeks second unit. The unit reconvened two months later and spent another two weeks doing second unit shots and re-staging some stunts in May.[5]

Shooting took place in and around Melbourne. Many of the car chase scenes for Mad Max were filmed near the town of Little River, just north of Geelong. The movie was shot with a widescreen anamorphic lens, the first Australian film to use one. [6]

The film's post-production was done at Kennedy's house, with Wilson and Kennedy editing the film in Kennedy's bedroom on a home-built editing machine that Kennedy's father, an engineer, had designed for them. Wilson and Kennedy also edited the sound there.

Tony Patterson edited the film for four months, then had to leave because he was contracted to make Dimboola. George Miller took over editing with Cliff Hayes and they worked on it for three months. Kennedy and Miller did the fine cut.[5]

George Miller wanted a gothic, Bernard Hermann type score and hired Brian May after hearing his work for Patrick (1978).[3]

Vehicles

Max's yellow Interceptor was a 1974 Ford Falcon XB sedan (previously, a Victorian police car) with a 351 c.i.d. Cleveland V8 engine and many other modifications.[8]

The Big Bopper, driven by Roop and Charlie, was also a 1974 Ford Falcon XB sedan and also a former Victorian Police car, but was powered by a 302 c.i.d. V8.[9] The March Hare, driven by Sarse and Scuttle, was an in-line-six-powered 1972 Ford Falcon XA sedan (this car was formerly a Melbourne taxi cab).[10]

The most memorable car, Max's black Pursuit Special was a limited GT351 version of a 1973 Ford XB Falcon Hardtop (sold in Australia from December 1973 to August 1976) which was primarily modified by Murray Smith, Peter Arcadipane and Ray Beckerley.[11] After filming of the first movie was completed, the car went up for sale but no buyers were found; eventually it was handed over to Murray Smith (film mechanic).

When production of Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior began, the car was purchased back by George Miller for use in the sequel. Once filming was over the car was left at a wrecking yard in Adelaide and was bought and restored by Bob Forsenko. Eventually it was sold again and is currently on display in the Cars of the Stars Motor Museum in Cumbria, England.The museum recently closed and the Black on Black car is currently in a collection in the Dezer museum in the US, Miami.[12]

The Nightrider's vehicle, another Pursuit Special, was a 1972 Holden HQ LS Monaro coupe.[13]

The car driven by the young couple that is destroyed by the bikers is a 1959 Chevrolet Impala sedan.

Of the motorcycles that appear in the film, 14 were KZ1000s donated by Kawasaki. All were modified in appearance by Melbourne business La Parisienne – one as the MFP bike ridden by 'The Goose' and the balance for members of the Toecutter's gang, played in the film by members of a local Victorian motorcycle club, the Vigilantes.[14]

By the end of filming, 14 vehicles had been destroyed in the chase and crash scenes, including the director's personal Mazda Bongo (the small, blue van that spins uncontrollably after being struck by the Big Bopper in the film's opening chase).

Release

Mad Max was initially released in Australia through Roadshow Entertainment (now Village Roadshow Pictures) in 1979.[15]

The movie was sold overseas for $1.8 million, with American International Pictures to release in the US and Warner Brothers to handle the rest of the world.[6]

When shown in the U.S. during 1980, the original Australian dialogue was revoiced by an American crew.[16] American International Pictures distributed this dub after it underwent a management re-organisation.[17] Much of the Australian slang and terminology was also replaced with American usages (examples: "Oi!" became "Hey!", "See looks!" became "See what I see?", "windscreen" became "windshield", "very toey" became "super hot", and "proby" -probationary officer- became "rookie"). AIP also altered the operator's duty call on Jim Goose's bike in the beginning of the movie (it ended with "Come on, Goose, where are you?"). The only dubbing exceptions were the voice of the singer in the Sugartown Cabaret (played by Robina Chaffey), the voice of Charlie (played by John Ley) through the mechanical voice box, and Officer Jim Goose (Steve Bisley), singing as he drives a truck before being ambushed. Since Mel Gibson was not well known to American audiences at the time, trailers and TV spots in the USA emphasised the film's action content.

The original Australian dialogue track was finally released in North America in 2000 in a limited theatrical reissue by MGM, the film's current rights holders. It has since been released in the U.S. on DVD with both the US and Australian soundtracks on separate tracks.[18][19]

Both New Zealand and Sweden initially banned the film, the former due to the scene where Goose is burned alive inside his vehicle. It mirrored an incident with a real gang shortly before the film's release. It was later shown in New Zealand in 1983 after the success of the sequel, with an 18 certificate.[20] The ban in Sweden was removed in 2005 and it has been shown on TV and is also available in video stores.

Reception

The film initially polarised critics. In a 1979 review, the Australian social commentator and film producer Phillip Adams condemned Mad Max, saying that it had "all the emotional uplift of Mein Kampf" and would be "a special favourite of rapists, sadists, child murderers and incipient [Charles] Mansons."[21] After the initial US release, Tom Buckley of The New York Times called it "ugly and incoherent".[22] However, Variety magazine praised the directorial debut by Miller.[23] As of June 2012, the film had a 95% "Fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes,[24] and is widely considered as one of the best films of 1979.[25][26][27] In 2004, The New York Times placed the film on its Best 1000 Movies Ever list.[28]

Though the film had a limited run in North America and earned only $8 million there, it did very well elsewhere around the world and went on to earn $100 million worldwide.[29] Since it was independently financed with a reported budget of just A$400,000, it was a major financial success. For 20 years, the movie held a record in Guinness Book of Records as the highest profit-to-cost ratio of a motion picture, conceding the record only in 1999 to The Blair Witch Project.[30] The film was awarded three Australian Film Institute Awards in 1979 (for editing, sound, and musical score). It was also nominated for Best Film, Best Director, Best Original Screenplay and Best Supporting Actor (Hugh Keays-Byrne) by the American Film Institute. The film also won the Special Jury Award at the Avoriaz Fantastic Film Festival.[31]

In popular culture

Box office

Mad Max grossed $5,355,490 at the box office in Australia,[32] which is equivalent to $20,939,966 dollars in 2009.

References

- ^ "Mad Max : SE". DVD Times. 19 January 2002. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

- ^ "Technical Specifications for Mad Max". IMDb.com. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ a b c Scott Murray & Peter Beilby, "George Miller: Director", Cinema Papers, May–June 1979 p369-371

- ^ James McCausland (4 December 2006). "Scientists' warnings unheeded". The Courier-Mail. News.com.au. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d Peter Beilby & Scott Murray, "Byron Kennedy", Cinema Papers, May–June 1979 p366

- ^ a b c David Stratton, The Last New Wave: The Australian Film Revival, Angus & Robertson, 1980 p241-243

- ^ Mary Packard and the editors of Ripley Entertainment, ed. (2001). Ripley's Believe It or Not! Special Edition. Leanne Franson (illustrations) (1st ed. ed.). Scholastic Inc. ISBN 0-439-26040-X.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|editor=has generic name (help) - ^ "Mad Max Cars – Max's Yellow Interceptor (4 Door XB Sedan)". Madmaxmovies.com. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ "''Mad Max'' Cars – Big Boppa/Big Bopper". Madmaxmovies.com. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ "''Mad Max'' Cars – March Hare". Madmaxmovies.com. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ "''Mad Max'' Movies – The History of the ''Interceptor'', Part 1". Madmaxmovies.com. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ "Cars of the Stars Motor Museum". Carsofthestars.com. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- ^ "''Mad Max'' Cars – The Nightrider's Monaro". Madmaxmovies.com. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ "''Mad Max'' Cars – Toecutter's Gang (Bikers)". Madmaxmovies.com. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ^ Moran, Albert; Vieth, Errol (2005). "Kennedy Miller Productions". Historical Dictionary of Australian and New Zealand Cinema. Scarecrow Press. p. 174. ISBN 0-8108-5459-7. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ Herx, Henry (1988). "Mad Max". The Family Guide to Movies on Video. The Crossroad Publishing Company. p. 163 (pre-release version). ISBN 0-8245-0816-5.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ McFarlane, Brian (1988). Australian Cinema. Columbia University Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-231-06728-3. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Gibson's Voice Returns on New 'Mad Max' DVD". Los Angeles Times. 29 December 2001. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) [dead link] - ^ "Mad Max (1979)". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ Carroll, Larry (3 February 2009). "Greatest Movie Badasses Of All Time: Mad Max – Movie News Story | MTV Movie News". Mtv.com. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ^ Phillip Adams, The Bulletin, 1 May 1979; cited by urban cinefile, 2010, "Mad Max". Adams has since remained a prominent opponent of screen violence. He has also been consistent in his criticism of Mel Gibson's political and social opinions.

- ^ Buckley, Tom (14 June 1980). "Mad Max". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 April 2010. [dead link]

- ^ By (1 January 1979). "Mad Max Review – Read Variety's Analysis Of The Movie Mad Max". Variety.com. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- ^ "Mad Max". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ "The Best Movies of 1979 by Rank". Films101.com. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ^ "Best Films of 1979". Listal.com. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ^ "Most Popular Feature Films Released in 1979". IMDb.com. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ^ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made". The New York Times. 29 April 2003. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- ^ "Mad Max". The Numbers. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ "Cost-to-Earnings Ratio". thealmightyguru.com. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ^ Awards for Mad Max at IMDb

- ^ Film Victoria – Australian Films at the Australian Box Office

External links

- Official website – home to the original Mad Max movie, maintained by members of the cast and crew.

- Mad Max at IMDb

- Mad Max at the TCM Movie Database

- Mad Max at AllMovie

- Mad Max at Rotten Tomatoes

- Use dmy dates from May 2011

- 1979 films

- 1970s action films

- American International Pictures films

- Australian action films

- Australian films

- Australian science fiction films

- Directorial debut films

- Dystopian films

- English-language films

- Films directed by George Miller

- Films set in Australia

- Films shot anamorphically

- Films shot in Melbourne

- Mad Max

- Peak oil films

- Post-apocalyptic films

- Road movies

- Vigilante films