Manual of The Mother Church

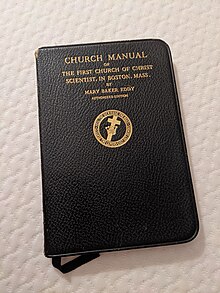

The 89th and final edition of the Manual of the Mother Church | |

| Author | Mary Baker Eddy |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Published |

|

| Publisher | Christian Science Publishing Society |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print, ebook, audiobook |

| Pages | 138 (89th ed.) |

| Website | christianscience.com |

The Church Manual of The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston, Massachusetts commonly known as the Manual of The Mother Church is the book that establishes the structure and governance of The First Church of Christ, Scientist, also known as The Mother Church, functioning like a constitution. It was written by Mary Baker Eddy, founder of the church. It was first published in 1895 and was revised dozens of times. The final edition, the 89th, was published in 1910.

Background

Writing in September 1895 to Septimus J. Hanna, then an editor of Christian Science periodicals and First Reader of The Mother Church, Eddy described the work of establishing the various by-laws as having been "impelled" by circumstances which made the need for a rule apparent.[1] The impetus was always the future protection of the church, to fortify its structural integrity by preventing battles for personal control and creeping bureaucracy, and to maintain its spiritual integrity by preventing frivolous experimentation and the intrusions of personal opinion that would eventually adulterate the teaching and doctrine of Christian Science.[2][3][n 1] The final revision of the Manual, the 89th edition, was published two weeks after Eddy's death in December 1910, although she had approved and signed the proof sheets of the edition before publication.[5][6]

Church constitution

SECTION 1. Neither animosity nor mere personal attachment should impel the motives or acts of the members of The Mother Church. In Science, divine Love alone governs man; and a Christian Scientist reflects the sweet amenities of Love, in rebuking sin, in true brotherliness, charitableness, and forgiveness. The members of this Church should daily watch and pray to be delivered from all evil, from prophesying, judging, condemning, counseling, influencing or being influenced erroneously.

The Manual was first published in 1895.[1] Like a constitution, it establishes the framework for the government and operations of the church, as well as its "basic character".[7] Its by-laws are organized into 35 articles that establish the duties and responsibilities of church officers, provide guidelines and rules for Christian Science practitioners and teachers, define the responsibilities of individual members and provide the means of discipline. The "Rule for Motives and Acts" (at right) typifies the nature of these by-laws[7] and is the only by-law that was barely changed through the dozens of revisions.[9]

As a lay church, there is no hierarchy. All members, including church officers, are bound by the rules of the Manual.[10] Under the Manual, the church officers comprising the Board of Directors are charged with administration,[7] and have no authority to govern the church, amend or interpret by-laws or create new ones.[11][n 2] Eddy vested the authority for government of the church not in persons, but in the by-laws of the Manual itself.[1][11]

Branch churches are set up to be democratic and independent, related to but not controlled by The Mother Church.[1][7] The appendix includes membership applications, the order of the church services, Sunday school and testimony meetings, as well as two deeds related to land conveyance for The Mother Church. As legal documents describing the Board of Directors and setting limits to their authority, they cement the legal foundation for Eddy's intent regarding the Manual as the church's constitution.[11][n 3] Adam Dickey, Eddy's last personal secretary, whom she appointed to the Board of Directors shortly before she died,[13] wrote in 1922, "The safety of the Christian Science church does not rest in the Board of Directors; it lies in the integrity of each individual member, and in the determination of the members to obey the By-laws."[11]

Estoppel clauses

There are 32 by-laws with "estoppel clauses" in the Manual, where Eddy's consent is required.[11] A few of her students, including William R. Rathvon and Judge Septimus J. Hanna, concerned about the ramifications of these clauses in the event of her death, urged her to remove them. Henry Moore Baker, a lawyer and politician who was also Eddy's cousin, assured her and others in the church that when she was gone clauses in the Manual which required her involvement would default to the "next in authority", which in this case would be the Board of Directors.[14][15][n 4] However, after Eddy's passing some people both within and without of the church believed that without Eddy's presence the Manual could not function as it had before, with some believing the church should dissolve and others that the Trustees of the Christian Science Publishing Society should function as a separate governing body within the church.[17][18] This culminated in a period of litigation in 1921 when the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court upheld the Baker interpretation that the Board of Directors assumed jurisdiction over the estoppel clauses upon Eddy's death.[15] However, according to Eddy biographer Robert Peel, the estoppel clauses still add "moral force" and make it "morally incumbent upon the [Board of] Directors" to take particular care to fulfill the 'spirit and letter' when considering steps governed by those by-laws.[15]

The 1991 publication of a book by Bliss Knapp again sparked controversy in the church around the estoppel clauses that resulted in another lawsuit. The book, which had previously been refused publication as being incompatible with Eddy's teaching, had been named in two wills with a large bequest to the church if it published the book. Critics accused the Board, then in need of funds to cover losses stemming from The Christian Science Monitor's entry into television, of violating the Manual's estoppel clauses in order to receive the funds.[19]

Notes

- ^ Christian Science historian Stephen Gottschalk writes, "The evidence shows that [Eddy] thought in centuries where most of [her followers] thought in years. The gradual paganizing of Christianity in the ancient world was an ever-present reminder to her of the possible secularizing of Christian Science in the future through the attrition of its radical reliance on spiritual as opposed to material means."[4]

- ^ Until 1903, the Board of Directors did have the authority, with Eddy's approval or direction, to amend most by-laws. In 1903, the by-law that granted this right was revised by Eddy to stipulate that she alone would have authority to alter church law and doctrine. The Board was not denied the right, rather the by-law no longer mentioned the Board at all. The change was reinforced by the addition of a second deed of trust to the Appendix, in which this revision was reiterated.[11]

- ^ In 1898, in another deed of trust, Eddy established the Christian Science Publishing Society and a Board of Trustees to manage it, stipulating the purpose of the Publishing Society in the deed, as to "more effectually [promote] and [extend] the religion of Christian Science as taught by me." Septimus J. Hanna, then editor of the Christian Science Journal, said that a few days before the deed was signed, Eddy asserted her desire "to protect and preserve the literature of the movement in its purity and from aggressive attempts ... to adulterate the literature by injecting into it thoughts and teachings which would tend to becloud or destroy her teachings of Christian Science and thereby create chaos and confusion in the Christian Science ranks as well as to misrepresent her teachings to the outside world."[12]

- ^ According to William R. Rathvon, Baker told him: "It is a matter of common law in a case of this kind, where it is physically impossible to carry out specified conditions by the one named, that the next in authority assume that jurisdiction. And in this case the next in authority is the Board of Directors of the Mother Church. Any competent court in the land will uphold the Manual just as Mrs. Eddy intends it to function whether her signature is forthcoming or not."[16]

References

- ^ a b c d Peel, Robert (1977), Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Authority. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, pp. 90-91.

- ^ Gottschalk, Stephen (2006), Rolling Away The Stone. Indiana University Press, pp. 242-243 and 394.

- ^ Peel, Robert (1977), p. 225.

- ^ Gottschalk, Stephen (2006), p. 227.

- ^ "What is the background of the 'Present Order of Services' in the Manual of the Mother Church?" Archived 2012-08-15 at the Wayback Machine Mary Baker Eddy Library (June 5, 2012). Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ^ "Did Eddy authorize the 89th edition of the Manual?" Mary Baker Eddy Library (October 13, 2020). Retrieved Aug 31, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e John, DeWitt (1962), The Christian Science Way of Life. The Christian Science Publishing Society, pp. 68-69.

- ^ Article VIII, "Guidance of Members" Archived 2013-07-24 at the Wayback Machine Manual of The Mother Church, The First Church of Christ, Scientist website. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ^ Gottschalk, Stephen (2006), p. 244.

- ^ Gottschalk, Stephen (2006), p. 241.

- ^ a b c d e f Gottschalk, Stephen (2006), pp. 242-243.

- ^ Gottschalk, Stephen (2006), pp. 255-256.

- ^ Gottschalk, Stephen (2006), pp. 316 and 359.

- ^ Beasley, Norman (1956), The Continuing Spirit. Duell, Sloan and Pearce, pp. 142-144.

- ^ a b c Peel, Robert (1977), pp. 346-347.

- ^ Beasley, Norman (1956), pp. 143-144.

- ^ Beasley, Norman (1956), p. 144.

- ^ Melton, Gordon J. (1999), Encyclopedia of American religions. Gale Research, p. 140.

- ^ Anker, Roy M. (1999), Self-Help and Popular Religion in Modern American Culture: An Interpretive Guide. Greenwood Press, pp. 81-82. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

External links

- Read online: Manual of The Mother Church, 89th Edition - Official website

- 1st edition of the Manual of the Mother Church - archive.org

- 89th (final) edition of the Manual of the Mother Church - archive.org