Moonrise Kingdom

| Moonrise Kingdom | |

|---|---|

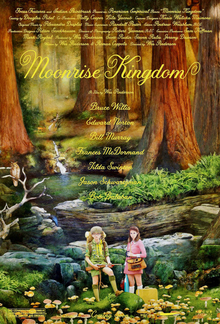

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Wes Anderson |

| Written by | Wes Anderson Roman Coppola |

| Produced by | Wes Anderson Scott Rudin Steven Rales Jeremy Dawson |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Yeoman |

| Edited by | Andrew Weisblum |

| Music by | Alexandre Desplat |

Production companies | American Empirical Pictures Indian Paintbrush |

| Distributed by | Focus Features |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 94 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $16 million[2] |

| Box office | $68.3 million[2] |

Moonrise Kingdom is a 2012 American coming-of-age film directed by Wes Anderson, written by Anderson and Roman Coppola, and described as an "eccentric, pubescent love story". It features newcomers Jared Gilman and Kara Hayward in the main roles and an ensemble cast.[3][4][5] Filming took place in Rhode Island from April to June 2011.[6] Worldwide rights to the independently produced film were acquired by Focus Features.[6]

While preparing the script for Moonrise Kingdom, director Wes Anderson viewed films about young love for inspiration, including Black Jack, Small Change, A Little Romance, and Melody.[7]

The film received critical acclaim, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay, and was nominated for the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy.[8] The film was later chosen to be the 95th greatest film since 2000 in an international critics' poll conducted by BBC.[9]

Plot

In September 1965, on the fictitious New England island of New Penzance, 12-year-old orphan Sam Shakusky is attending Camp Ivanhoe, a Khaki Scout summer camp led by Scoutmaster Randy Ward. Suzy Bishop, also 12, lives on the island with her parents, Walt and Laura, both attorneys, and her three younger brothers in a house called Summer's End. Sam and Suzy, both introverted, intelligent and mature for their age, met in the summer of 1964 during a church performance of Noye's Fludde and have been pen pals since then. Their relationship having become romantic over the course of their correspondence, they have made a secret pact to reunite and run away together. Sam brings camping equipment, and Suzy brings her binoculars, six books, her kitten, and her brother's battery-powered record player. They hike, camp, and fish together in the wilderness with the goal of reaching a secluded cove on the island. Meanwhile, the Khaki Scouts have become aware of Sam's absence, finding a letter that he left behind stating that he has resigned his position as a Khaki Scout. Scoutmaster Ward tells the Khaki Scouts to use their skills to create a search party and find Sam.

Eventually, Sam and Suzy are confronted by a group of Khaki Scouts who try to capture them and, during the resulting altercation, Suzy injures the Scouts' de facto leader, Redford, with her scissors and Camp Ivanhoe's dog is killed by a stray shot from a bow and arrow wielded by one of the Scouts. The Scouts flee and Sam and Suzy hike to the cove which they name Moonrise Kingdom. They set up camp and go swimming. Later, while drying off, they begin dancing to Françoise Hardy in their underwear. As the romantic tension between them grows, they kiss repeatedly.

Suzy's parents, Scoutmaster Ward, the Scouts from Camp Ivanhoe, and Island Police Captain Duffy Sharp find Sam and Suzy in their tent at the cove. Suzy's parents take her home and when Sharp contacts the foster parents he is told that they no longer wish to house Sam. He stays with Sharp while they await the arrival of "Social Services"—an otherwise nameless woman with plans to place Sam in a "juvenile refuge" and to explore the possibility of treating him with electroshock therapy.

The Camp Ivanhoe Scouts have a change of heart and decide to help the couple. Together, they paddle to a neighboring St. Jack Wood Island to seek out the help of Cousin Ben, an older relative of one of the Scouts. Ben works at Fort Lebanon, a larger Khaki Scout summer camp located on St. Jack Wood Island and run by Commander Pierce, who is Ward's boss. Ben decides that the best available option is to try to get Sam and Suzy aboard a crabbing boat anchored off the island so that Sam can work as a crewman and avoid Social Services, but before leaving he performs a "wedding" ceremony, which he admits is not legally binding. Sam and Suzy never make it onto the crabbing boat, and instead are pursued by Suzy's parents, Captain Sharp, Social Services, and the scouts of Fort Lebanon under the command of Scoutmaster Ward.

A violent hurricane and flash flood strike only three days after Sam and Suzy first ran away from home and, after many twists and turns, Sharp apprehends Sam and Suzy on the steeple of the church in which they first met. The steeple is destroyed by lightning, but everyone survives. During the storm, Sharp decides to become Sam's legal guardian, thus saving Sam from the orphanage, as well as allowing him to remain on New Penzance Island and maintain contact with Suzy.

At Summer's End, Sam is painting a landscape of Moonrise Kingdom. Suzy and her brothers are called to dinner. On slipping out of the window to join Sharp in his patrol car, Sam tells Suzy that he will see her the following day.

Cast

- Bruce Willis as Captain Sharp

- Edward Norton as Scout Master Ward

- Bill Murray as Mr. Bishop

- Frances McDormand as Mrs. Bishop

- Tilda Swinton as Social Services

- Jared Gilman as Sam

- Kara Hayward as Suzy

- Jason Schwartzman as Cousin Ben

- Harvey Keitel as Commander Pierce

- Bob Balaban as the Narrator

Production

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2015) |

Cinematographer Robert Yeoman shot the movie on Super 16mm film (with a 1.85:1 aspect ratio), using Aaton Xterà and A-Minima cameras.[10]

The film was shot at various places around Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island including Conanicut Island, Prudence Island, Fort Wetherill,[11] Yawgoog Scout Reservation, Trinity Church, Conanicut Island Light, and Newport's Ballard Park.[12]

Google Earth was used for initial location scouting, according to director Anderson. "We had to figure out where we were shooting this movie—in Canada or Michigan or New England ... ? We started out with "Where is this girl [Suzy’s] house, and where is the naked wildlife we want?" So [after Googling], we traveled around a bit, to Cumberland Island in Georgia, to the Thousand Islands on the New York/Ontario border ... we checked out all these locations."[13]

A house in the Thousand Islands region in New York was used as the model for the interior of Suzy’s house on the set built for the movie. The set for the Bishop home was constructed and filmed inside of a former Linens 'n Things store in Middletown, Rhode Island.[14][11] Conanicut Island Light, a decommissioned Rhode Island lighthouse, was used for the exterior.[13]

Fictitious books and maps

In the film, 12-year-old Suzy packs six fictitious storybooks that she stole from the public library. Six artists were commissioned to create the jacket covers for the books, and Wes Anderson wrote passages for each of them. Suzy is shown reading aloud from three of the books during the film. Anderson had considered incorporating animation for the reading scenes, but chose to show her reading with the other actors listening spellbound. In April 2012, Anderson decided to animate all six books and use them in a promotional video in which the film’s narrator Bob Balaban introduces the segment for each.[15]

Anderson described designing the maps for the fictitious New Penzance Island and St. Jack Wood Island: "It's weird because you'd think that you could make a fake island and map it, and it would be a simple enough matter, but to make it feel like a real thing, it just always takes a lot of attention."[16] Anderson further stated that the movie "has maps, and it has books, and it has watercolor paintings and needle-points, and a lot of different things that we had to make. And all these things just take forever, but I feel like even if they don't get that much time [on screen], you kind of feel whether or not they’ve got the layers of the real thing in them."[16]

Release

The film premiered on May 16, 2012 as the opening film at the 2012 Cannes Film Festival—the first film of Wes Anderson to play at Cannes, where it was screened in competition.[7][17] It was released in French theaters the same day. The American limited release occurred on May 25, and set a record for the best per-theater-average for a non-animated movie by grossing an average of $130,752 in four theaters.[18]

Finishing its theatrical run on November 1, 2012, Moonrise Kingdom grossed $45,512,466 domestically and $22,750,700 in international markets for a worldwide total of $68,263,166.[2]

Home media

Moonrise Kingdom was released on DVD and Blu-ray in the United Kingdom on October 1, 2012.[19] In the United States, the film was released on October 16, 2012 in two formats: a one-disc DVD, and a two-disc Blu-ray + DVD combo pack with a digital copy.[20] The Criterion Collection released both a DVD and Blu-ray release on September 22, 2015.[21]

Reception

Critical response

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2013) |

Moonrise Kingdom received widespread acclaim; review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a rating of 94% based on reviews from 233 critics, with an average score of 8.2/10.[22] The consensus states, "Warm, whimsical, and poignant, the immaculately framed and beautifully acted Moonrise Kingdom presents writer/director Wes Anderson at his idiosyncratic best." Review aggregation website Metacritic gives the film a weighted average score of 84 (out of 100), based on 43 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim."[23]

Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian gives the film 4 stars out of 5, calling it "another sprightly confection of oddities, attractively eccentric, witty and strangely clothed".[24] Christopher Orr of The Atlantic wrote that Moonrise Kingdom "captures the texture of childhood summers, the sense of having a limited amount of time in which to do unlimited things" and is "Anderson's best live-action feature" because "it takes as its primary subject matter odd, precocious children, rather than the damaged and dissatisfied adults they will one day become."[25]

Kristen M. Jones of Film Comment wrote that the film "has a spontaneity and yearning that lend an easy comic rhythm", but it also has a "rapt quality, as if we are viewing the events through Suzy's binoculars or reading the story under the covers by a flashlight."[26]

Top ten lists

Moonrise Kingdom was listed on many critics' top ten lists.[27]

- 1st – Lou Lumenick, New York Post

- 1st – Mike Russell, The Oregonian

- 1st – David Germain, Associated Press

- 1st – Sam Adams, The A.V. Club

- 1st – Richard Brody, The New Yorker (tied with Holy Motors)

- 2nd – Gabe Toro, Indiewire

- 2nd – Kristopher Tapley, Hitfix

- 2nd – Keith Phipps, The A.V. Club

- 2nd – Rene Rodriguez, Miami Herald

- 2nd – Bill Goodykoontz, Arizona Republic

- 3rd – Glenn Kenny, MSN Movies

- 3rd – Karina Longworth, Aaron Hills, & Michelle Orange, The Village Voice

- 4th – Ty Burr, The Boston Globe

- 4th – Jessica Kiang, Indiewire

- 4th – Jake Coyle, Associated Press

- 4th – Mike Scott, The Times-Picayune

- 5th – Steven Rea, Philadelphia Inquirer

- 5th – Mike D'Angelo & Nathan Rabin, The A.V. Club

- 5th – Christopher Orr, The Atlantic

- 5th – Betsy Sharkey, Los Angeles Times (tied with Beasts of the Southern Wild)

- 6th – Scott Tobias, The A.V. Club

- 6th – Wesley Morris, The Boston Globe

- 7th – Oliver Lyttelton, Indiewire

- 8th – Christy Lemire, Associated Press

- 9th – Peter Knegt, Indiewire

- 9th – Peter Travers, Rolling Stone

- 9th – Anne Thompson, Indiewire

- 9th – Drew McWeeny & Gregory Ellwood, Hitfix

- 9th – J. Hoberman, Artforum (tied with Beasts of the Southern Wild)

- 10th – Michael Phillips, Chicago Tribune

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – Bob Mondello, NPR

- Top 10 (ranked alphabetically) – Claudia Puig, USA Today

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – Phillip French, The Observer

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – David Denby, The New Yorker

- Top 10 (ranked alphabetically) – Stephen Whitty, The Star-Ledger

- Top 10 (ranked alphabetically) – Richard Lawson, The Atlantic

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – Joe Morgenstern, The Wall Street Journal

- Top 10 (ranked alphabetically) – Joe Williams & Calvin Wilson, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically) – Manohla Dargis, The New York Times]

- Best of 2012 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Rob Hunter, Film School Rejects

Accolades

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipients and nominees | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[28] | February 24, 2013 | Best Writing (Original Screenplay) | Wes Anderson and Roman Coppola | Nominated |

| American Cinema Editors[29] | February 16, 2013 | Best Edited Feature Film - Comedy or Musical | Andrew Weisblum | Nominated |

| American Film Institute[30] | December 2012 | AFI Award for Movie of the Year | Jeremy Dawson, Scott Rubin, Steven M. Rales, Wes Anderson | Won |

| AFI Film Award | Moonrise Kingdom | Won | ||

| Austin Film Critics Association[31] | December 18, 2012 | Best Film | Moonrise Kingdom | Nominated |

| Bodil Awards[32] | March 16, 2013 | Best American Film | Moonrise Kingdom | Nominated |

| British Academy of Film and Television Arts[33] | February 10, 2013 | Original Screenplay | Wes Anderson, Roman Coppola | Nominated |

| Broadcast Film Critics Association | January 10, 2013 | Best Film | Moonrise Kingdom | Nominated |

| Best Young Performer | Kara Hayward | Nominated | ||

| Best Cast | Moonrise Kingdom cast | Nominated | ||

| Best Original Screenplay | Wes Anderson, Roman Coppola | Nominated | ||

| Best Composer | Alexandre Desplat | Nominated | ||

| Cannes Film Festival[34] | May 27, 2012 | Palme d'Or | Wes Anderson | Nominated |

| Golden Globe Awards[8] | January 13, 2013 | Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Moonrise Kingdom | Nominated |

| Gotham Awards[35] | November 26, 2012 | Best Ensemble Performance | Moonrise Kingdom cast | Nominated |

| Best Feature | Moonrise Kingdom | Won | ||

| Guldbagge Awards[36] | January 21, 2013 | Best Foreign Film | Moonrise Kingdom | Nominated |

| Independent Spirit Awards[37] | February 23, 2013 | Best Cinematography | Robert Yeoman | Nominated |

| Best Director | Wes Anderson | Nominated | ||

| Best Feature | Moonrise Kingdom | Nominated | ||

| Best Screenplay | Wes Anderson, Roman Coppola | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Male | Bruce Willis | Nominated | ||

| Producers Guild of America | January 26, 2013 | Best Picture | Scott Rudin & Wes Anderson, Jeremy Dawson, Steven M. Rales | Nominated |

| Writers Guild of America | February 17, 2013 | Best Original Screenplay | Wes Anderson and Roman Coppola | Nominated |

| San Diego Film Critics Society[38] | December 11, 2012 | Best Original Screenplay | Wes Anderson, Roman Coppola | Nominated |

| Best Production Design | Adam Stockhausen | Nominated | ||

| Best Score | Alexandre Desplat | Nominated | ||

| Satellite Awards[39] | December 16, 2012 | Best Original Screenplay | Wes Anderson, Roman Coppola | Nominated |

| Best Picture | Moonrise Kingdom | Nominated | ||

| World Soundtrack Awards[40] | October 20, 2012 | Soundtrack Composer of the Year | Alexandre Desplat | Nominated |

| Young Artist Awards[41] | May 5, 2013 | Best Performance in a Feature Film - Leading Young Actor | Jared Gilman | Nominated |

| Best Performance in a Feature Film - Leading Young Actress | Kara Hayward | Nominated |

Soundtrack

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

The original score was composed by Alexandre Desplat, who worked previously with Anderson on Fantastic Mr. Fox, with percussion compositions by frequent Anderson collaborator Mark Mothersbaugh. The final credits of the film features a deconstructed rendition of Desplat's original soundtrack in the style of Britten's Young Person's Guide, accompanied by a child's voice to introduce each instrumental section.

The soundtrack also features music by Benjamin Britten, a composer notable for his many works for children's voices. At Cannes, during the post-screening press conference, Anderson said,

The Britten music had a huge effect on the whole movie, I think. The movie's sort of set to it. The play of Noye's Fludde that is performed in it—my older brother and I were actually in a production of that when I was ten or eleven, and that music is something I've always remembered, and made a very strong impression on me. It is the colour of the movie in a way.[42]

With many Britten tracks taken from recordings conducted or supervised by the composer himself, the music includes The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra (Introduction/Theme; Fugue), conducted by Leonard Bernstein; Friday Afternoons ("Cuckoo"; "Old Abram Brown"); Simple Symphony ("Playful Pizzicato"); Noye's Fludde (various excerpts, including the processions of animals into and out of the ark, and "The spacious firmament on high"); and A Midsummer Night's Dream ("On the ground, sleep sound").[43]

Also featured are extracts from Saint Saens's Carnaval des Animaux, Franz Schubert's An Die Musik and tracks by Hank Williams.

References

- ^ "Moonrise Kingdom (12A)". British Board of Film Classification. May 8, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ a b c Moonrise Kingdom at Box Office Mojo

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (May 16, 2012). "Moonrise Kingdom: Cannes Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- ^ Weisberg, Jacob (May 17, 2012). "Wes Anderson on directing Bruce Willis, Edward Norton for the first time". Slate. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- ^ Allin, Olivia (January 13, 2012). "Bill Murray and Wes Anderson reunite for 'Moonrise Kingdom'". OnTheRedCarpet. Retrieved May 6, 2012.

- ^ a b Thompson, Anne (May 2, 2011). "Wes Anderson's New Movie Moonrise Kingdom Starring Willis, Norton, and Murray Goes to Focus Features". Indiewire.com. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ a b Hornaday, Ann (June 2, 2012). "Wes Anderson talks about 'Moonrise Kingdom' and his Cannes debut". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- ^ a b "2013 Golden Globe Nominations". December 14, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- ^ "The 21st century's 100 greatest films". BBC. August 23, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Heuring, David (May 25, 2012). "Cinematographer Robert Yeoman Talks Super 16 Style on Moonrise Kingdom". studiodaily.com. Studio Daily. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ a b ""Moonrise Kingdom" release is set". The Newport Daily News. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ Jennifer Nicole Sullivan (June 6, 2012). "Enchanted "Kingdom"". NewportRI.com. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Karpel, Ari. "Moving Storyboards and Drumming: Wes Anderson Maps Out the Peculiar Genius of "Moonrise Kingdom"". Co.Create. Fast Company. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ^ Muther, Christopher. "Creating "Moonrise Kingdom" in Rhode Island with Wes Anderson's production designer Adam Stockhausen - The Boston Globe". The Boston Globe. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ^ Vary, Adam (June 7, 2012). "'Moonrise Kingdom': Wes Anderson's animated take on the film's imaginary books". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ^ a b Vary, Adam (June 1, 2012). "'Moonrise Kingdom' director Wes Anderson on its box office record and casting his young leads". Inside Movies. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes - From 16 to 27 may 2012". Festival-cannes.fr. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ^ Smith, Grady (May 28, 2012). "Box office report: 'Men in Black 3' tops Memorial Day weekend with $70M; 'Moonrise Kingdom' huge in limited release". Inside Movies blog. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ^ "Moonrise Kingdom". Filmdates.co.uk. October 1, 2012. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ "Moonrise Kingdom Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. August 14, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Moonrise Kingdom". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Moonrise Kingdom at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Moonrise Kingdom at Metacritic

- ^ Peter Bradshaw (May 24, 2012). "Moonrise Kingdom – review". Guardian. London. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- ^ Orr, Christopher (June 1, 2012). "The Youthful Magic of 'Moonrise Kingdom'". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ^ Jones, Kristen M. "Moonrise Kingdom". Film Comment. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ Dietz, Jason (December 11, 2012). "2012 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Fleming, Mike. "Seth MacFarlane And Emma Stone To Announce Oscar Nominations". Deadline.com. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ "Nominees & Recipients". ACE Film Editors. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ American Film Institute. "Afi Awards". Afi.com. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ "2012 Awards - Austin Film Critics Association". Austinfilmcritics.org. December 18, 2012. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ "Velkommen til". Bodilprisen.dk. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ "Film Awards Nominations Announcement in 2013 - Film Awards - Film". The BAFTA site. January 9, 2013. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ "Wes Anderson's Moonrise Kingdom opens Cannes Film Festival". BBC News. BBC. May 17, 2012. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- ^ Knegt, Peter; Smith, Nigel M (November 26, 2012). "'Moonrise Kingdom,' 'Beasts of the Southern Wild' Lead Gotham Award Winners". IndieWire. SnagFilms. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- ^ "Nomineringarna till Guldbaggen" (in Swedish). Sydsvenskan.se. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- ^ Harp, Justin (November 27, 2012). "'Moonrise Kingdom', 'Silver Linings' among Independent Spirit nominees". Digital Spy. Hearst Magazines UK. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- ^ "San Diego Film Critics Nominate Top Films for 2012". San Diego Film Critics Society. December 9, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ^ Harp, Justin (December 4, 2012). "'Les Misérables' earns ten Satellite Award nominations". Digital Spy. Hearst Magazines UK. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ "World Soundtrack Awards Announces 2012 Nominees". World Soundtrack Academy. Flanders International Film Festival. August 22, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "34th Annual Young Artist Awards". YoungArtistAwards.org. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- ^ "Moonrise Kingdom: What's the Britten music used in Wes Anderson's new movie?". Britten Pears Foundation. 2012. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ Evan Minske (May 2, 2012). "Wes Anderson's Moonrise Kingdom Soundtrack: Check Out the Tracklist and a Piece of the Score". Retrieved July 28, 2012.

External links

- 2012 films

- 2010s comedy-drama films

- 2010s coming-of-age films

- American comedy-drama films

- American coming-of-age films

- American films

- English-language films

- Films directed by Wes Anderson

- Films about orphans

- Films set in 1965

- Films set in New England

- Films set on islands

- Films shot in Rhode Island

- Focus Features films

- Entertainment One films

- StudioCanal films

- Universal Pictures films

- Screenplays by Roman Coppola

- Screenplays by Wes Anderson

- Scouting in popular culture

- Summer camps in films

- Films produced by Scott Rudin

- Films scored by Alexandre Desplat