Moss Cass

Moss Cass | |

|---|---|

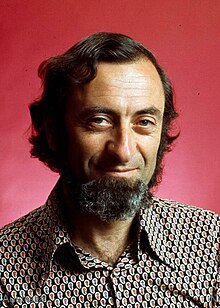

Cass in 1973 | |

| Minister for the Media | |

| In office 6 June 1975 – 11 November 1975 | |

| Prime Minister | Gough Whitlam |

| Preceded by | Doug McClelland |

| Succeeded by | Reg Withers |

| Minister for Environment and Conservation | |

| In office 19 December 1972 – 6 June 1975 As Minister for the Environment: 21 April 1975 – 6 June 1975 | |

| Prime Minister | Gough Whitlam |

| Preceded by | Peter Howson |

| Succeeded by | Jim Cairns |

| Member of the Australian Parliament for Maribyrnong | |

| In office 25 October 1969 – 4 February 1983 | |

| Preceded by | Philip Stokes |

| Succeeded by | Alan Griffiths |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 February 1927 Narrogin, Western Australia, Australia |

| Died | 26 February 2022 (aged 95) Melbourne, Victoria, Australia |

| Political party | Labor |

| Alma mater | University of Sydney |

| Occupation | Medical practitioner |

Moses Henry Cass (18 February 1927 – 26 February 2022) was an Australian doctor and politician who held ministerial office in the Whitlam government. He served as Minister for Environment and Conservation (1972–1975), the Environment (1975), and the Media (1975). He represented the Division of Maribyrnong in the House of Representatives from 1969 to 1983.

Early life[edit]

Cass was born in Narrogin, Western Australia[1] to Jewish parents who had fled Tsarist Russia to escape antisemitism.[2] His paternal grandfather, Moses Cass, was born in Białystok, Vistula Land, Tsarist Russia (now Poland), arriving in Perth in 1906.[3]

Cass studied medicine at the University of Sydney and during the 1950s and 1960s worked as a registrar at hospitals in Sydney, London and Melbourne. He was a research fellow at Melbourne's Royal Children's Hospital and conducted research into the use of a heart–lung machine for open-heart surgery. He was the first medical director (from 1964 to 1969) of the Trade Union Clinic and Research Centre, which became the Western Region Health Centre (now merged into the cohealth community health organisation).[4]

He became known as a proponent of abortion law reform[1] and was the spokesman for the Abortion Reform Association.[5] On a radio broadcast in June 1969, Cass stated "I have certainly broken the law on numerous occasions by sending patients to other doctors for the purpose of having abortions induced." He stated that he had performed abortions "every weekend" at Royal North Shore Hospital while undergoing his residency and that he was "sure that most doctors are in the same position".[6]

Politics[edit]

Cass joined the Australian Labor Party (ALP) in 1955.[1] He ran for the Kew City Council in 1961 but lost after the distribution of preferences.[7] He stood in safe Liberal seats at the 1961 and 1963 elections, running against Prime Minister Robert Menzies in Kooyong and John Jess in La Trobe.[1]

At the 1969 federal election, Cass defeated incumbent Liberal MP Philip Stokes in the Division of Maribyrnong.[8] He was appointed Minister for Environment and Conservation following the election of the Whitlam government in 1972. He appointed marine biologist Don McMichael as his departmental secretary.[9] Cass held the second-lowest rank in cabinet, above only science minister Bill Morrison. He was assisted in his environmental protection efforts by Rex Connor, the Minister for Minerals and Energy. Connor used his seniority in the party to overcome opposition to Cass's proposals, notably helping secure the passage of the Environment Protection (Impact of Proposals) Act 1974.[10]

Cass was unsuccessful in seeking to prevent the flooding of Lake Pedder in Tasmania. Nonetheless, he did lay the groundwork for the end of sandmining on Fraser Island and government protection of the Great Barrier Reef. In 1975 he led parliamentarians and ALP branch members in expressing concerns about the effects of uranium mining. A key concern was the adverse effect that uranium mining would have on the northern Aboriginal people. Cass said: "nuclear energy creates the most dangerous, insidious and persistent waste products, ever experienced on the planet".[11]

In October 1973, Cass seconded former prime minister John Gorton's motion for the decriminalisation of homosexuality, which was successful although it had no legal effect.[12] He also argued for the decriminalisation of marijuana.[1]

In April 1975, Cass's title was changed to just "Minister for the Environment", at his own request. He said the previous title was too long and redundant.[13] In June 1975, Cass relinquished the environment portfolio and instead was appointed Minister for the Media.[14] He announced plans for a voluntary Australian Press Council, but in September stated that a voluntary council would not be sufficient.[15] He was criticised by Rupert Murdoch, who stated it was "sinister" and constituted censorship. Cass stated that the proposal had been subjected to "bizarre distortion and hysterical over-reaction" by some sections of the press.[16]

Following the dismissal of the government and Labor's defeat at the 1975 election, Cass was named opposition spokesman for health in Whitlam's shadow cabinet.[17] When Bill Hayden replaced Whitlam as opposition leader in December 1977, Cass was given the portfolio of immigration and ethnic affairs.[18] He supported cutting immigration, stating there were not enough jobs for migrants.[19] In 1978, he stated that there was "considerable organisation" behind Vietnamese boat people coming to Australia.[20]

Cass announced in June 1982 that he would not recontest his seat at the next election.[21]

Later life and death[edit]

In 1983, Cass chaired a review into the Australian Institute of Multicultural Affairs.[22] In the same year he was appointed by the Hawke government to the council of the National Museum of Australia.[23]

Cass served as chair of the Australian National Biocentre from 2002 to 2003. He was also patron of the Sustainable Living Foundation and an honorary fellow at the Melbourne University School of Land and Environment.[1]

In 2007, Cass was a founding member of Independent Australian Jewish Voices, a "breakaway group from Australia's main pro-Israel Jewish lobby organisations".[24] During the Gaza War of 2009, he signed a statement condemning Israel's "grossly disproportionate military assault".[25]

His second child Deborah Cass was an academic lawyer at the London School of Economics whose writings and teaching were widely admired in Australia and overseas.[26] The Deborah Cass writing prize, a national writing prize for first and second generation migrant writers, was created after her death.[27]

Cass died on 26 February 2022, at the age of 95.[28][29][30][31]

Quotes[edit]

Cass is incorrectly believed by some to be the originator of the saying, "We do not inherit the earth from our ancestors; we borrow it from our children" (although a similar paraphrase was used earlier by the environmental activist Wendell Berry).[32] On 13 November 1974, when Cass was environment minister, he gave a speech in Paris to the meeting of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Borrowing heavily from Native American proverbs and traditions, he said:

We rich nations, for that is what we are, have an obligation not only to the poor nations, but to all the grandchildren of the world, rich and poor. We have not inherited this earth from our parents to do with it what we will. We have borrowed it from our children and we must be careful to use it in their interests as well as our own. Anyone who fails to recognise the basic validity of the proposition put in different ways by increasing numbers of writers, from Malthus to The Club of Rome, is either ignorant, a fool, or evil.

Cass's version was a longer explanation than the original, traditional proverb.

Cass has been cited as the first person to use the term "queue jumping" in reference to asylum seekers, in a 1978 opinion column in The Australian.[33]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f "Notes on Contributors" (PDF). The Whitlam Legacy. Federation Press. 2013. p. 485.

- ^ "Moss Cass reflects on his Jewish identity as a young man". Multicultural Research Library. 30 March 2009. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ Neumann, Klaus (2015). "Across the Seas: Australia's Response to Refugees: A History". Black Inc. ISBN 9781863957359.

- ^ "History". cohealth - care for all. cohealth. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

...the Clinic's first Medical Director, the visionary Dr Moss Cass...

- ^ "Jumbo jets, runway a feature". The Canberra Times. 11 October 1969. p. 10.

- ^ "Doctor 'sent woman for abortions'". The Canberra Times. 23 June 1969. p. 3.

- ^ "Doctor To Oppose P.M. At Elections". The Canberra Times. 22 April 1961. p. 3.

- ^ "Govt wins by seven seats". The Canberra Times. 6 November 1969. p. 10.

- ^ "Conservation authority may lead new department". The Canberra Times. 8 January 1973. p. 1.

- ^ "Rex Connor, a model for David Beddall". The Canberra Times. 5 December 1994. p. 11.

- ^ Jim Falk (1982). Global Fission: The Battle Over Nuclear Power, Oxford University Press, p. 258.

- ^ "Change in sex law backed". The Canberra Times. 17 October 1973. p. 25.

- ^ "The Week". The Canberra Times. 26 April 1975. p. 2.

- ^ "Sweeping changes to cabinet". The Canberra Times. 6 June 1975. p. 1.

- ^ "Cass criticises Press". The Canberra Times. 13 September 1975. p. 7.

- ^ "Cass 'not trying to curb Press'". The Canberra Times. 11 August 1975.

- ^ "'Shadow ministry' named". The Canberra Times. 30 January 1976. p. 1.

- ^ "Hayden names opposition executive". The Canberra Times. 30 December 1977. p. 1.

- ^ "Cass wants immigration cut". The Canberra Times. 20 February 1978. p. 1.

- ^ "Cass speculates on 'backing' for boat people". The Canberra Times. 5 January 1978. p. 3.

- ^ "Cass quits Parliament". The Canberra Times. 18 June 1982. p. 3.

- ^ "Review of multicultural institute". The Canberra Times. 26 July 1983. p. 9.

- ^ "Museum council appointed". The Canberra Times. 30 December 1983. p. 3.

- ^ Jackson, Andra (6 March 2007). "New group takes on Jewish lobby". The Age. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ West, Andrew; Pearlman, Jonathan (6 January 2009). "Australian Jews protest against Israel's action". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "Writer and educator saw law as a means to better the world". The Sydney Morning Herald. 1 August 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Deborah Cass Prize, The – Writer's Marketplace". writersmarketplace.com.au. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Warburton, Mark [@MarkLWarburton] (26 February 2022). "Vale Moss Cass who died today. Minister in Whitlam Govt. progressive advocate for the environment; health care; abortion, drug & homosexual law reform; reducing global inequality - a few of the areas in which he led us. A brave & fierce independent thinker. Thank you, Moss" (Tweet). Retrieved 28 February 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ Farnsworth, Malcolm. "The Deceased Whitlam Ministers". Whitlam Dismissal. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ "Vale, Moss Cass". Whitlam Institute. 28 February 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Wright, Tony (6 March 2022). "Moss Cass: pot-smoking Cabinet minister who helped change Australia". The Age. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "We Do Not Inherit the Earth from Our Ancestors; We Borrow It from Our Children". Quote Investigator. 22 January 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ^ Lester, Eve (2018). "Making Migration Law: The Foreigner, Sovereignty, and the Case of Australia". Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 9781316800263.

Further reading[edit]

- Cass, Moss; Encel, Vivien; O'Donnell, Anthony (2017). Moss Cass and the Greening of the Australian Labor Party. Australian Scholarly Publishing. ISBN 9781925588446.

- 1927 births

- 2022 deaths

- 1975 Australian constitutional crisis

- 20th-century Australian politicians

- Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of Australia

- Australian abortion-rights activists

- Australian medical doctors

- Australian medical researchers

- Australian people of Polish-Jewish descent

- Jewish Australian politicians

- Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Maribyrnong

- Members of the Cabinet of Australia

- People from Narrogin, Western Australia

- University of Sydney alumni