Neutering: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 153: | Line 153: | ||

[[zh:絕育]] |

[[zh:絕育]] |

||

poop |

poop |

||

hi craig |

|||

Revision as of 13:46, 23 September 2008

Neutering, from the Latin neuter (of neither sex[1]), is the removal of an animal's reproductive organ, either all of it or a considerably large part. It is the most drastic surgical procedure with sterilizing purposes. The process is also referred to as castration for males and as spaying for females. Colloquially, it is often referred to as fixing. In male horses, the process is referred to as gelding.

Unlike in humans, neutering is the most common sterilizing method in animals. In the USA, most humane societies, animal shelters and rescue groups (not to mention numerous commercial entities) urge pet owners to have their pets "spayed or neutered" to prevent the births of unwanted litters, contributing to the overpopulation of animals. In Europe, the procedure is less commonly performed, especially in dogs.

Health and behavioral effects

Advantages

In addition to being a birth control method, neutering has the following health and behavioural benefits:

- Hormone-associated benign prostatic hypertrophy (enlarged prostate) is prevented.

- Female cats and dogs are seven times more likely to develop mammary tumors if they are not spayed before their first heat cycle.[2] The risk is generally estimated at 25% over a lifetime in unspayed females.

- Pyometra is prevented, either due to the removal of the organ (when ovariohysterectomy is performed) or due to the cervix remaining permanently closed because of the lack of oestrogens caused by spaying.

- Uterine cancer, Ovarian cancer and Testicular cancer are prevented due to the removal of the susceptible organs. These cancers are uncommon in dogs and cats. In female rabbits, however, the rate of uterine cancer may be as high as 80%. [3]

- Sexual mounting and urine marking by male dogs, as well as spraying by male cats, is reduced or eliminated, especially when performed in animals that have not yet reached puberty.

Disadvantages

General

- As with any surgical procedure, immediate complications of neutering include the usual anesthetic and surgical complications, such as bleeding and infection. These risks are relatively low in routine spaying and neutering; however, they may be increased for some animals due to other pre-existing health factors.

- Neutered dogs and cats of both genders have an increased risk of obesity. Theories for this include reduced metabolism, reduced activity, and eating more due to altered feeding behavior.[4].

- Neutered dogs of both genders are at a twofold excess risk to develop osteosarcoma as compared to intact dogs[5],[6][7] as well as an increased risk of hemangiosarcoma[8][9] and urinary tract cancer.[10]

- Neutered dogs of both genders have an increased risk of adverse reactions to vaccinations.[11]

Specific to Males

- Neutered male dogs display a fourfold increased incidence of prostate cancer over intact males.[13][14]

- In addition, neutered male dogs are at higher risk than intact males of developing moderate to severe geriatric cognitive impairment (geriatric cognitive impairment includes disorientation in the house or outdoors, changes in social interactions with human family members, loss of house training, and changes in the sleep-wake cycle).[15]

- As compared to intact males, male neutered cats are at an increased risk for certain problems associated with feline lower urinary tract disease, including the presence of stones or a plug in the urethra and urethral blockage.[16]

Specific to Females

- Spayed female dogs can develop urinary incontinence.[17][18][19]

- Spayed female dogs are at an increased risk of hypothyroidism[20]

- Despite the risk of pyometra being greatly reduced in spayed females, Stump pyometra may still occur in this group.

Ambiguous

Most animals lose their libido due to the hormonal changes involved with both genders, and females no longer experience heat cycles, which are sometimes considered a major nuisance factor, especially in female cats. Minor personality changes may occur in the animal. Neutering is often recommended in cases of undesirable behavior in dogs. Studies indicate[citation needed] that roaming, urine marking, and mounting are reduced in about 60% of neutered males, but one study found little effect of neutering on aggression and other issues.[21] Intact male cats are more prone to urine spraying, while many common behavioral causes of urine marking remain in castrated cats.

Methods

Females (spaying)

In female animals, spaying involves abdominal surgery to remove the ovaries and uterus (ovario-hysterectomy). Alternatively, it is also possible to remove the ovaries and leave the uterus inside (ovariectomy), which is mainly done in cats and young female dogs. Spaying is commonly practiced on household pets such as cats and dogs as a method of birth control, but is rarely performed on livestock.

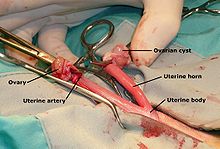

The surgery is usually performed through a ventral (belly) midline incision below the umbilicus (belly button). The incision size varies depending upon the surgeon and the size of the animal. The uterine horns are identified and the ovaries are found by following the horns to their ends.

There is a ligament that attaches the ovaries to the kidneys which may need to be broken so the ovaries can be identified. The ovarian arteries are then ligated twice (tied-off) with resorbable suture material and then the arteries transected (cut). The uterine body (which is very short in litter bearing species) and related arteries are also tied off just in front of the cervix (leaving the cervix as a natural barrier). The entire uterus and ovaries are then removed. The abdomen is checked for bleeding and then closed with a 3 layer closure. The linea alba (muscle layer) and then the subcutaneous layer (fat under skin) are closed with resorbable suture material. The skin is then stapled, sutured, or glued closed.

See also oophorectomy and hysterectomy.

Males (castration)

In male animals, castration involves the removal of the testes, and is commonly practiced on both household pets (for birth control) and on livestock (for birth control, as well as to improve commercial value).

For more information, see castration and gelding (specific to horses).

Nonsurgical alternatives

Injectable

- Male dogs - Neutersol (Zinc gluconate neutralized by arginine). Cytotoxic; produces infertility by chemical disruption of the testicle. It is no longer produced.

- Male rats - Adjudin (analogue of indazole-carboxylic acid), induces reversible germ cell loss from the seminiferous epithelium by disrupting cell adhesion function between nurse cells and immature sperm cells, preventing maturation.

- Male sheep and pigs - Wireless Microvalve.[22] Using a piezoelectric polymer that will deform when exposed to a specific electric field broadcast from a key fob (like a car alarm) the valve will open or close, preventing the passage of sperm, but not seminal fluid. Located in a section of the vas deferens that occurs just after the epididymis, the implantation can be carried out by use of a hypodermic needle.

- Female mammals - Vaccine of antigens (derived from purified Porcine zona pellucida) encapsulated in liposomes (cholesterol and lecithin) with an adjuvant, latest US patent RE37,224 (as of 2006-06-06), CA patent 2137263 (issued 1999-06-15). Product commercially known as SpayVac,[23] a single injection causes a treated female mammal to produce antibodies that bind to ZP3 on the surface of her ovum, blocking sperm from fertilizing it for periods from 22 months up to 7 years (depending on the animal[24][25]). This will not prevent the animal from going into heat (ovulating) and other than birth control, none of the above mentioned advantages or disadvantages apply.

Other

- Noninvasive vasectomy using ultrasound.[26]

Surgical alternatives

Vasectomy: The snipping and tying of the vasa deferentia (plural of vas deferens). Failure rates are insignificantly small. This procedure is routinely carried out on male ferrets and sheep to manipulate the estrus cycles of in-contact females. It is uncommon in other animal species.

Tubal Ligation: Snipping and tying of fallopian tubes as a sterilization measure can be performed on female cats and dogs. Risk of unwanted pregnancies is insignificantly small. Only a few veterinarians will perform the procedure.

Like other forms of neutering, vasectomy and tubal ligation eliminate the ability to produce offspring. They differ from neutering in that they leave the animal's levels and patterns of sex hormone unchanged. Both sexes will retain their normal reproductive behavior, and other than birth control, none of the advantages and disadvantages listed above apply. This method is favored by some of the people who want to infringe on the natural state of companion animals as little as necessary to achieve the reduction of unwanted births of cats and dogs.

Penile translocation is sometimes performed in cattle to produce a "teaser bull", which retains its full libido, but is incapable of intromission. This is done to identify estrous cows without the risk of transmitting venereal diseases. [1]

Terminology for neutered animals

Male animals

Neutered males of given animal species sometimes have specific names:

- Cat, ferret - Gib

- Cattle - Bullock, Ox, Steer, Stag

- Chicken - Capon

- Deer - Havier

- Goat - Wether, Dinmont

- Horse - Gelding

- Pig - Barrow

- Rabbit - Lapin

- Sheep - Wether, Dinmont

Female animals

A specialized vocabulary in animal husbandry and fancy has arisen for spayed females of given animal species:

Religious views on neutering

Christianity

Judaism

Traditional interpretations of Orthodox Judaism forbids the castration of both humans and animals by Jews,[27] except in lifesaving situations.[28] In 2007, the Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Israel Rabbi Shlomo Amar issued a ruling stating that it is permissible to have companion animals spayed or neutered on the basis of the Jewish mandate to prevent cruelty to animals.[29]

Islam

While there are differing views in Islam with regard to neutering animals,[30] some Islamic association have stated that when done to maintain the health and welfare of both the animals and the community, neutering is allowed on the basis of 'maslahat' (general good)[31] or "choos[ing] the lesser of two evils".[32]

Buddhism

Miscellaneous

- TV celebrities Bob Barker and Drew Carey helped to popularize the spay-or-neuter drive by closing every episode of The Price Is Right with a request for people to help control the pet population by spaying or neutering their pets. In the movie Shrek 2, Donkey proposed that Puss in Boots be given the "Bob Barker Treatment", an indirect reference to neutering.

References

- ^ University of Notre Dame online Latin dictionary

- ^ Morrison, Wallace B. (1998). Cancer in Dogs and Cats (1st ed.). Williams and Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-06105-4.

- ^ http://www.veterinarypartner.com/Content.plx?P=A&A=489

- ^ German AJ (2006). "The growing problem of obesity in dogs and cats". J. Nutr. 136 (7 Suppl): 1940S–1946S. PMID 16772464.

- ^ Priester, W. A. and McKay, F. W. (1980). "The occurrence of tumors in domestic animals". Natl Cancer Inst Monograph 54: 169.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ru, B., Terracini, G.; et al. (1998). "Host related risk factors for canine osteosarcoma". Vet J 156(1):31-9. 156: 31. doi:10.1016/S1090-0233(98)80059-2.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cooley, D. M., Beranek, B. C.; et al. (2002). "Endogenous gonadal hormone exposure and bone sarcoma risk". Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11(11): 1434-40. PMID 12433723.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Prymak C, McKee LJ, Goldschmidt MH, Glickman LT. (1988). "Epidemiologic, clinical, pathologic, and prognostic characteristics of splenic hemangiosarcoma and splenic hematoma in dogs: 217 cases (1985)". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 193 (6): 706–712.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ware WA, Hopper DL (1999). "Cardiac Tumors in Dogs". J Vet Intern Med. 13: 95–103. doi:10.1892/0891-6640(1999)013<0095:CTID>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ Sanborn, L.J. (2007). "Long-Term Health Risks and Benefits Associated with Spay / Neuter in Dogs" (PDF).

- ^ Moore GE, Guptill LF, Ward MP, Glickman NW, Faunt KF, Lewis HB, Glickman LT. (2005). "Adverse events diagnosed within three days of vaccine administration in dogs". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 227 (7): 1102–1108. doi:10.2460/javma.2005.227.1102.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ettinger, Stephen J.;Feldman, Edward C. (1995). Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine(4th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-6795-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Teske E, Nann EC, van Dijk EM, van Garderen E, Schalken JA (2002). "Canine prostate carcinoma: epidemiological evidence of an increased risk in castrated dogs". Mol Cell Endocrinol. 197 (1–2): 251–255. doi:10.1016/S0303-7207(02)00261-7.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sorenmo KU, Goldschmidt M, Shofer F, Ferrocone J (2003). "Immunohistochemical characterization of canine prostatic carcinoma and correlation with castration status and castration time". Vet Comparative Oncology. 1 (1): 48–56. doi:10.1046/j.1476-5829.2003.00007.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hart BL. (2001). "Effect of gonadectomy on subsequent development of age-related cognitive impairment in dogs". J Am Vet Med Assoc. 219 (1): 51–6. doi:10.2460/javma.2001.219.51. PMID 11439769.

- ^ Lekcharoensuk C, Osborne CA, Lulich JP (2001). "Epidemiologic study of risk factors for lower urinary tract diseases in cats". J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 218 (9): 1429–35. doi:10.2460/javma.2001.218.1429. PMID 11345305.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thrusfield MV, Holt PE, Muirhead RH. (1998). "Acquired urinary incontinence in bitches: its incidence and relationship to neutering practices". J Small Anim Pract. 39 (12): 559–566. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.1998.tb03709.x.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arnold S, Arnold P, Hubler M, Casal M, Rŭsch P (1989). "Urinary incontinence in spayed bitches: prevalence and breed disposition". Europ J of Compan Anim Pract. 131 (5): 259–263.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Thrusfield Mv (1985). "Association between urinary incontinence and spaying in bitches". Vet Rec. 116: 695.

- ^ Panciera DL (1994). "Hypothyroidism in dogs: 66 cases (1987-1992)". J Amer Vet Med Assoc. 204 (5): 761–767.

- ^ Neilson J., Eckstein R., Hart B (1997). "Effects on castration on problem behaviors in male dogs with reference to age and duration of behavior". JAVMA. 211 (2): 180–182.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jones, Inke (2008-01-17). "Wireless RF communication in biomedical applications" (pdf). Smart Materials and Structures. 17. IOP Publishing Ltd: 8–9. doi:10.1088/0964-1726/17/1/015050. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ SpayVac. Retrieved on early 2003.

- ^ Gary Killian, Nancy K. Diehl, Lowell Miller, Jack Rhyan, David Thain (2007). "Long-term Efficacy of Three Contraceptive Approaches for Population Control of Wild Horses". Cattlemen's Update: 48–63.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ DeNicola, Anthony (2007-03-16). "Status of Present Day Infertility Technology". Northeast Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fried NM, Sinelnikov YD, Pant BB, Roberts WW, Solomon SB (2001). "Noninvasive vasectomy using a focused ultrasound clip: thermal measurements and simulations". Biomedical Engineering, IEEE Transactions on. 48 (12): 1453–9. doi:10.1109/10.966604. PMID 11759926.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ What does Jewish law say about neutering male pets?

- ^ Feinstein, Moshe. Igrot Moshe.

- ^ CHAI - Why Spay/Neuter is Crucial

- ^ Islam Question and Answer - De-clawing a cat so that it won’t do any damage, and neutering/spaying cats

- ^ What some religions say about sterilisation.

- ^ http://www.spca.org.my/neuter.htm#5 Spaying/Neutering Information

External links

- DVM Article on health effects of spay/neuter: Long-Term Health Risks and Benefits Associated with Spay / Neuter in Dogs

- CanineSports.com article: Early Spay-Neuter Considerations for the Canine Athlete

- American Humane Society info on spaying and neutering

- Animalpeoplenews.org: Early age neutering

- Canine Spay Photos and Description

poop hi craig