Nondualism

| Part of a series on |

| Spirituality |

|---|

| Outline |

| Influences |

| Research |

Nondualism, also called non-duality, may refer to the nonduality of absolute and relative (advaya) in the Mahayana Buddhist tradition, the non-difference of Ātman and Brahman in the Advaita Vedanta tradition, and "nondual-consciousness",[note 1] the non-duality of subject and object, in modern spirituality.

"Non-duality" is a term and concept used to define various strands of religious and spiritual thought.[1] It is found in a variety of Asian religious traditions,[2] but with a variety of meanings and uses.[2][1]

Its origins are situated within the Buddhist tradition, with its teaching of advaya, the nonduality of the absolute and the relative.[3][4] The term has more commonly become associated with the Advaita Vedanta-tradition of Adi Shankara, which states that there is no difference between Brahman and Ātman.[5]

In various strands of modern spirituality, New Age and Neo-Advaita, the "primordial, natural awareness without subject or object"[web 1] is seen as the essence of a variety of religious traditions.[6]

Definitions

Dictionary definitions of "nondualism" are scarce.[web 2] The main definitions are the nonduality of Absolute and relative (Advaya), the non-difference of Atman and Brahman (Advaita), and nondual consciousness.[note 2]

Advaya and Advaita

A distinction can be made between advaya and advaita.[7][note 3]

- "Advaya" is an epistemological approach.[9] It is knowledge free from the duality of the extremes of "is" and "is not".[9] It is the Buddhist Middle Way between eternalism and annihilationism. In Mahayana Buddhism, the Middle Way refers to the insight into emptiness that transcends opposite statements about existence.[10][note 4][note 5]

- "Advaita" is an ontological approach.[9] It is knowledge of a differenceless entity, namely Brahman (Vedanta) or Vijñāna.[9][note 6]

Definition 1: Advaya - Non-duality of absolute and relative

According to this definition or usage, nonduality refers to the nonduality of between absolute and relative. It is the recognition that ultimately every"thing" is devoid of an everlasting and independent "essence", and yet our commonday experience of "things" is in itself also true.[note 7]. This is a common theme in both Buddhism and Advaita Vedanta,[3] and is also reflected in Tantra and Bhedabheda Vedanta. It is also recognized by some modern Indian traditions, especially Neo-Vedanta.

Definition 2: Advaita - Identity of Atman and Brahman

According to this definition or usage, nonduality refers to "Advaita", which means that there is no difference between Brahman and Ātman.[5] Brahman is pure Being, Consciousness and Bliss (Sat-cit-ananda).[19] Only Brahman is real; the empirical world is unreal, appearance.[20] Advaita is best known from the Adi Shankara, who harmonised Gaudapada's ideas with the Upanishadic texts, but has become a broad current in Indian culture and religions and encompasses more than only Shankara's thought.

Definition 3: Nondual consciousness

Usage in western spirituality

The term has gained attention in western spirituality, where various traditions are seen as driven by the same non-dual experience.[21] Nondual consciousness is "[A] primordial, natural awareness without subject or object",[web 1][3] The idea of a "nondual consciousness" has gained attraction and popularity in western spirituality and New Age-thinking. It is recognized in the Asian traditions, but also in western and Mediterranean religious traditions, and in western philosophy.[6]

David Loy sees non-duality between subject and object as a common thread in Taoism, Mahayana Buddhism & Advaita Vedanta.[3][note 8] According to Loy, referred by Pritcher:

...when you realize that the nature of your mind and the [U]niverse are nondual, you are enlightened.[23]

Perceived similarities

This nondual consciousness is perceived in a wide variety of religious traditions:

- Hinduism:

- Upanishad[24]

- The Advaita Vedanta of Shankara[25][24]

- Tantra[26] and Kashmira Shaivism[27][26]

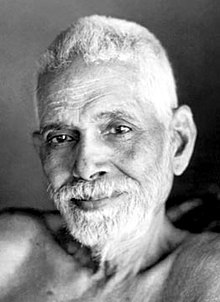

- Ramana Maharshi

- The Inchegeri Sampradaya of Siddharameshwar Maharaj and Nisargadatta Maharaj, which belongs to the Nath tradition

- Buddhism:

- Sikhism[37]

- Taoism[38]

- Subud[6]

- Abrahamic traditions:

- Sufism[38]

- Western philosophy:

- Neo-platonism[citation needed]

Advaya - Non-duality of absolute and relative

Advaya is the non-duality of absolute and relative. It has its origins in Buddhist thought on the nature of existence and liberation, but is also recognized by Tantra and Advaita Vedanta.

Buddhism

Origins

Pratityasamutpada, "dependent co-arising", is a basic teaching in Buddhism: everything arises in dependence upon multiple causes and conditions; nothing exists as a singular, independent entity. This means that there are no essences: every"thing" is anātman, devoid of a self or essence. According to Bhikkhu Bodhi:[web 4]

According to the Pali Suttas, the individual being is merely a complex unity of the five aggregates, which are all stamped with the three marks of impermanence, suffering, and selflessness. Any postulation of selfhood in regard to this compound of transient, conditioned phenomena is an instance of "personality view" (sakkayaditthi), the most basic fetter that binds beings to the round of rebirths. The attainment of liberation, for Buddhism, does not come to pass by the realization of a true self or absolute "I," but through the dissolution of even the subtlest sense of selfhood in relation to the five aggregates, "the abolition of all I-making, mine-making, and underlying tendencies to conceit."[web 4]

Insight into anātman and pratityasamutpada is one of the basic factors of the Four Noble Truths and the Buddhist path to liberation. It is variously called prajna, bodhi and vipassana. In the beginning of the first millennium CE this insight into emptiness came to be regarded as an "absolute" in itself, as in the Buddha-nature doctrine. The two truths doctrine, as expounded by the Madhyamaka-school, was a response against these absolutist tendencies.[39][40]

Levels of truth

Various schools of Buddhism discern levels of truth:

- The Two truths doctrine of the Madhyamaka

- The Three Natures of the Yogacara

- Essence-Function, or Absolute-relative in Chinese and Korean Buddhism

- The Trikaya-formule, consisting of

- The Dharmakāya or Truth body which embodies the very principle of enlightenment and knows no limits or boundaries;

- The Sambhogakāya or body of mutual enjoyment which is a body of bliss or clear light manifestation;

- The Nirmāṇakāya or created body which manifests in time and space.[41]

Madhyamaka - Two truths Doctrine

Madhyamaka, also known as Śūnyavāda, refers primarily to a Mahāyāna Buddhist school of philosophy[42] founded by Nāgārjuna. According to Madhyamaka all phenomena are empty of "substance" or "essence" (Sanskrit: svabhāva) because they are dependently co-arisen. Likewise it is because they are dependently co-arisen that they have no intrinsic, independent reality of their own.

Dependent existence

In Chapter 15 of the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā Nagarjuna centers on the words svabhava [note 9] parabhava[note 10] bhava [note 11] and abhava.[note 12] Nagarjuna rejects the notion of inherent or independent existence.[49] The rejection of inherent existence does not imply that there is no existence at all.[46] What it does mean is that there is no "unique nature or substance (svabhava)"[44] in the "things" we perceive:

What Nagarjuna is saying is that no being has is a fixed and permanent nature.[50][note 13]

Madhyamaka also rejects the existence of an absolute reality or Self.[40] Ultimately, "absolute reality" is not an absolute, or the non-duality of a personal self and an absolute Self, but the deconstruction of such reifications.

Madhyamaka - Two truths

The distinction between the two truths (satyadvayavibhāga) was fully expressed by the Madhyamaka-school. In Nāgārjuna's Mūlamadhyamakakārikā it is used to defend the identification of dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda) with emptiness (śūnyatā):

The Buddha's teaching of the Dharma is based on two truths: a truth of worldly convention and an ultimate truth. Those who do not understand the distinction drawn between these two truths do not understand the Buddha's profound truth. Without a foundation in the conventional truth the significance of the ultimate cannot be taught. Without understanding the significance of the ultimate, liberation is not achieved.[52]

Nāgārjuna based his statement of the two truths on the Kaccāyanagotta Sutta. In the Kaccāyanagotta Sutta, the Buddha, speaking to the monk Kaccayana Gotta on the topic of right view, describes the Middle Way between nihilsm and eternalism:

By and large, Kaccayana, this world is supported by a polarity, that of existence and non-existence. But when one sees the origination of the world as it actually is with right discernment, "non-existence" with reference to the world does not occur to one. When one sees the cessation of the world as it actually is with right discernment, "existence" with reference to the world does not occur to one.[53]

Yogacara - Three natures

Yogācāra (Sanskrit; literally: "yoga practice"; "one whose practice is yoga")[54] is an influential school of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing phenomenology and (some argue) ontology[55] through the interior lens of meditative and yogic practices. It developed within Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism in about the 4th century CE.[56]

Vijñapti-mātra

One of the main features of Yogācāra philosophy is the concept of vijñapti-mātra. It is often used interchangeably with the term citta-mātra, but they have different meanings. The standard translation of both terms is "consciousness-only" or "mind-only." Several modern researchers object this translation, and the accompanying label of "absolute idealism" or "idealistic monism".[57] A better translation for vijñapti-mātra is representation-only.[58]

According to Kochumuttom, Yogacara is a realistic pluralism. It does not deny the existence of individual beings:[57]

What it denies are:

- That the absolute mode of reality is consciousness/mind/ideas,

- That the individual beings are transformations or evolutes of an absolute consciousness/mind/idea,

- That the individual beings are but illusory appearances of a monistic reality.[59]

Vijñapti-mātra then means "mere representation of consciousness:

[T]he phrase vijñaptimātratā-vāda means a theory which says that the world as it appears to the unenlightened ones is mere representation of consciousness. Therefore, any attempt to interpret vijñaptimātratā-vāda as idealism would be a gross misunderstanding of it.[58]

The term vijñapti-mātra replaced the "more metaphysical"[60] term citta-mātra used in the Lankavatara Sutra.[61] The Lankavatara Sutra "appears to be one of the earliest attempts to provide a philosophical justification for the Absolutism that emerged in Mahayana in relation to the concept of Buddha".[62] It uses the term citta-mātra, which means properly "thought-only". By using this term it develops an ontology, in contrast to the epistemology of the term vijñapti-mātra. The Lankavatara Sutra equates citta and the absolute. According to Kochumuttom, this not the way Yogacara uses the term vijñapti:[63]

[T]he absolute state is defined simply as emptiness, namely the emptiness of subject-object distinction. Once thus defined as emptiness (sunyata), it receives a number of synonyms, none of which betray idealism.[64]

Three Natures

The Yogācārins defined three basic modes by which we perceive our world. These are referred to in Yogācāra as the three natures of perception. They are:

- Parikalpita (literally, "fully conceptualized"): "imaginary nature", wherein things are incorrectly comprehended based on conceptual construction, through attachment and erroneous discrimination.

- Paratantra (literally, "other dependent"): "dependent nature", by which the correct understanding of the dependently originated nature of things is understood.

- Pariniṣpanna (literally, "fully accomplished"): "absolute nature", through which one comprehends things as they are in themselves, uninfluenced by any conceptualization at all.

Also, regarding perception, the Yogācārins emphasized that our everyday understanding of the existence of external objects is problematic, since in order to perceive any object (and thus, for all practical purposes, for the object to "exist"), there must be a sensory organ as well as a correlative type of consciousness to allow the process of cognition to occur.

Hua-yen Buddhism

The Huayan school or Flower Garland is a tradition of Mahayana Buddhist philosophy that flourished in China during the Tang period. It is based on the Sanskrit Flower Garland Sutra (S. Avataṃsaka Sūtra, C. Huayan Jing) and on a lengthy Chinese interpretation of it, the Huayan Lun. The name Flower Garland is meant to suggest the crowning glory of profound understanding.

The most important philosophical contributions of the Huayan school were in the area of its metaphysics. It taught the doctrine of the mutual containment and interpenetration of all phenomena, as expressed in Indra's net. One thing contains all other existing things, and all existing things contain that one thing.

Distinctive features of this approach to Buddhist philosophy include:

- Truth (or reality) is understood as encompassing and interpenetrating falsehood (or illusion), and vice versa

- Good is understood as encompassing and interpenetrating evil

- Similarly, all mind-made distinctions are understood as "collapsing" in the enlightened understanding of emptiness (a tradition traced back to the Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna)

Huayan teaches the Four Dharmadhatu, four ways to view reality:

- All dharmas are seen as particular separate events;

- All events are an expression of the absolute;

- Events and essence interpenetrate;

- All events interpenetrate.[65]

Absolute and relative in Zen

The teachings of Zen are expressed by a set of polarities: Buddha-nature - sunyata,[66][67] absolute-relative,[68] sudden and gradual enlightenment.[69]

The Prajnaparamita Sutras and Madhyamaka emphasized the non-duality of form and emptiness: form is emptiness, emptiness is form, as the Heart Sutra says.[68] The idea that the ultimate reality is present in the daily world of relative reality fitted into the Chinese culture which emphasized the mundane world and society. But this does not tell how the absolute is present in the relative world. This question is answered in such schemata as the Five Ranks of Tozan[70] and the Oxherding Pictures.

Essence-function in Korean Buddhism

The polarity of absolute and relative is also expressed as "essence-function". The absolute is essence, the relative is function. They can't be seen as separate realities, but interpenetrate each other. The distinction does not "exclude any other frameworks such as neng-so or "subject-object" constructions", though the two "are completely different from each other in terms of their way of thinking".[71]

In Korean Buddhism, essence-function is also expressed as "body" and "the body's functions":

[A] more accurate definition (and the one the Korean populace is more familiar with) is "body" and "the body's functions". The implications of "essence/function" and "body/its functions" are similar, that is, both paradigms are used to point to a nondual relationship between the two concepts.[72]

A metaphor for essence-function is "A lamp and its light", a phrase from the Platform Sutra, where Essence is lamp and Function is light.[73]

Tantra

Tantra is a religious tradition that originated in India the middle of the first millennium CE, and has been practiced by Buddhists, Hindus and Jains throughout south and southeast Asia.[74] It views humans as a microcosmos which mirrors the macrocosmos.[75] Its aim is to gain access to the energy or enlightened consciousness of the godhead or absolute, by embodying this energy or consciousness through rituals.[75] It views the godhead as both transcendent and immanent, and views the world as real, and not as an illusion:[76]

Rather than attempting to see through or transcend the world, the practicioner comes to recognize "that" (the world) as "I" (the supreme egoity of the godhead): in other words, s/he gains a "god's eye view" of the universe, and recognizes it to be nothing other than herself/himself. For East Asian Buddhist Tantra in particular, this means that the totality of the cosmos is a "realm of Dharma", sharing an underlying common principle.[77]

Although Buddhism had merely become extinct in India at the time of Islamic rule, Tantrism was kept alive in the Hindu yogic traditions, such as the Nath, from which the Inchegeri Sampradaya of Nisargadatta Maharaj descends.[78] Ramakrishna too was a tantric adherent, although his tantric background was overlayed and smoothed with an Advaita interpretation by his student Vivekananda.[79]

Advaita Vedanta - Identity of Atman and Brahman

The nonduality of the Advaita Vedantins is of the identity of Brahman and the Atman:

Advaita Vedānta is a scripturally derived philosophy centred on the proposition, first found in early Upaniṣads (800–300 BC), that Brahman – the Absolute, the supreme reality – and the self (ātman) are identical.[80]

Etymology

"Advaita", Sanskrit a, not; dvaita, dual, translated as "nondualism", "nonduality" and "nondual". The term "nondualism" and the term "advaita" from which it originates are polyvalent terms. The English word's origin is the Latin duo meaning "two" prefixed with "non-" meaning "not".

The first usage of the terms are yet to be attested. The English term "nondual" was also informed by early translations of the Upanishads in Western languages other than English from 1775.

These terms have entered the English language from literal English renderings of "advaita" subsequent to the first wave of English translations of the Upanishads. These translations commenced with the work of Müller (1823–1900), in the monumental Sacred Books of the East (1879).

Max Müller rendered "advaita" as "Monism" under influence of the then prevailing discourse of English translations of the Classical Tradition of the Ancient Greeks, such as Thales (624 BCE–c.546 BCE) and Heraclitus (c.535 BCE–c.475 BCE).

Origins

The oldest exposition of Advaita Vedanta is written by Gauḍapāda (6th century CE),[5] who has traditionally been regarded as the teacher of Govinda bhagavatpāda and the grandteacher of Shankara. Gaudapda took over the Buddhist doctrines that ultimate reality is pure consciousness (vijñapti-mātra)[5][note 14] and "that the nature of the world is the four-cornered negation".[5][note 15] Gaudapada "wove [both doctrines] into a philosophy of the Mandukaya Upanisad, which was further developed by Shankara.[82][note 16]

Gaudapada also took over the Buddhist concept of "ajāta" from Nagarjuna's Madhyamaka philosophy,[11][12] which uses the term "anutpāda".[84] [note 17] "Ajātivāda", "the Doctrine of no-origination"[86][note 18] or non-creation, is the fundamental philosophical doctrine of Gaudapada.[86]

Adi Shankara (788 - 820), systematized the works of preceding philosophers.[87] His system of Vedanta introduced the method of scholarly exegesis on the accepted metaphysics of the Upanishads. This style was adopted by all the later Vedanta schools.[citation needed]

Shankara himself emphasises the duality between subject and object, as in his commentary on the Brahman Sutras:

It is obvious that the subject and the object — that is, the Self (Atman) and the Not-Self, which are as different as darkness and light are — cannot be identified with each other. It is a mistake to superimpose upon the subject or Self (that is, the "I," whose nature is consciousness) the characteristics of the object or Not-"I" (which is non-intelligent), and to superimpose the subject and its attributes on the object. Nonetheless, man has a natural tendency, rooted in ignorance (avidya), not to distinguish clearly between subject and object, although they are in fact absolutely distinct, but rather to superimpose upon each the characteristic nature and attributes of the other. This leads to a confusion of the Real (the Self) and the Unreal (the Not-Self) and causes us to say such [silly] things as "I am that," "That is mine," and so on...[web 8]

Levels of reality

Three levels of reality

Advaita took over from the Madhyamika the idea of levels of reality.[88] Usually two levels are being mentioned,[89] but Shankara uses sublation as the criterion to postulate an ontological hierarchy of three levels:[90][web 9]

- Pāramārthika (paramartha, absolute), the absolute level, "which is absolutely real and into which both other reality levels can be resolved".[web 9] This experience can't be sublated by any other experience.[90]

- Vyāvahārika (vyavahara), or samvriti-saya[89] (empirical or pragmatical), "our world of experience, the phenomenal world that we handle every day when we are awake".[web 9] It is the level in which both jiva (living creatures or individual souls) and Iswara are true; here, the material world is also true.

- Prāthibhāsika (pratibhasika, apparent reality, unreality), "reality based on imagination alone".[web 9] It is the level in which appearances are actually false, like the illusion of a snake over a rope, or a dream.

Four states of consciousness

The Mandukya Upanishad describes four states of consciousness, which correspond to the three bodies,[91] or four bodies as described by Siddharameshwar Maharaj:[92]

- The first state is the waking state, in which we are aware of our daily world. "It is described as outward-knowing (bahish-prajnya), gross (sthula) and universal (vaishvanara)".[web 10] This is the gross body.

- The second state is the dreaming mind. "It is described as inward-knowing (antah-prajnya), subtle (pravivikta) and burning (taijasa)".[web 10] This is the subtle body.

- The third state is the state of deep sleep. In this state the underlying ground of concsiousness is undistracted, "the Lord of all (sarv’-eshvara), the knower of all (sarva-jnya), the inner controller (antar-yami), the source of all (yonih sarvasya), the origin and dissolution of created things (prabhav’-apyayau hi bhutanam)".[web 10] This is the causal body.

- Turiya, pure consciousness, is the fourth state. It is the background that underlies and transcends the three common states of consciousness.[web 11] [web 12] In this consciousness both absolute and relative, Saguna Brahman and Nirguna Brahman, are transcended.[93] It is the true state of experience of the infinite (ananta) and non-different (advaita/abheda), free from the dualistic experience which results from the attempts to conceptualise ( vipalka) reality.[94] It is the state in which ajativada, non-origination, is apprehended.[94]

Modern understanding of "nondual consciousness"

A popular western understanding of "nondualism" is "nondual consciousness", "a primordial, natural awareness without subject or object"[web 13] called turiya and sahaja in Hinduism, and luminous mind, Buddha-nature and rigpa (among other terms) in Buddhism. It is used interchangeably with Neo-Advaita.[web 14] All terms refer to the Absolute, and its usage is different from adyiva, the non-dualism of absolute and relative reality.

Nonduality as common essence

This nondual consciousness is seen as a common stratum to different religions. Several definitions or meanings are combined in this approach, which makes it possible to recognize various traditions as having the same essence.[21] According to Renard, many forms of religion are based on an experiential or intuitive understanding of "the Real"[95] According to Wolfe,

The teachings of nonduality have begun to come of age in the West, recognized (at last) as the central essence of Zen, Dzochen, Tao, Vedanta, Sufism, and of Christians such as Meister Eckhart. In particular, the recorded teachings of sages (such as Ramana Maharshi and Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj) have paved the way for a contemporary generation of illuminating speakers and writers.[96]

Though the notion of nondualism as common essence is a modern notion, some of the included traditions themselves also refer to levels of truth which transcend even non-dualism. In Kashmir Shaivism, the term "paradvaita" is being used, meaning "the supreme and absolute non-dualism".[web 15] And Gaudapada, the grandteacher of Shankara, states that, from the absolute standpoint, not even "non-dual" exists.[97]

Nondualism and monism

Nondualism as common essence prefers the term "nondualism", instead of monism, because this understanding is "nonconceptual", "not graspapable in an idea".[95][note 19] Even to call this "ground of reality" "One" or "Oneness" is attributing a characteristic to that ground of reality. The only thing that can be said is that it is "not two" or "non-dual":[web 16]

Non-dualism is not monism. Unlike monism, non-dualism does not reduce everything to a conceptual unity. It simply confesses that ultimate reality is non-dual, beyond thought and speech, and this apprehension is arrived at through a supra-relational intuition. Not two does not imply "therefore, one." Not-two is meant to silence the chattering mind. Only when the mind has been silenced is the revelation of non-duality discovered.[98]

According to Renard, Alan Watts has been one of the main contributors to the popularisation of the non-monistic understanding of "nondualism".[95][note 20]

Development of the modern understanding of "nondualism"

The idea of nonduality as "the central essence"[96] is part of a modern mutual exchange and synthesis of ideas between western spiritual and esoteric traditions and Asian religious revival and reform movements.[note 21] Western predecessors are, among others, Orientalism, Transcendentalism, Theosophy, the idea of a Perennial Philosophy, New Age,[101] and Wilber's synthesis of western psychology and Asian spirituality.

Eastern movements are the Hindu reform movements such as Vivekananda's Neo-Vedanta and Aurobindo's Integral Yoga, the Vipassana movement, and Buddhist modernism.[note 22]

Orientalism

The western world has been exposed to Indian religious since the late 18th century.[102] In 1785 appeared the first western translation of a Sanskrit-text.[102] It marked the growing interest in the Indian culture and languages.[103] The first translation of Upanishads appeared in two parts in 1801 and 1802,[103] which influenced Arthur Schopenhauer, who called them "the consolation of my life".[104][note 23] Early translations also appeared in other European languages.[105]

Transcendentalism and Unitarian Universalism

Transcendentalism was an early 19th-century liberal Protestant movement that developed in the 1830s and 1840s in the Eastern region of the United States. It was rooted in English and German Romanticism, the Biblical criticism of Herder and Schleiermacher, and the skepticism of Hume.[web 17]

The Transcendentalists emphasised an intuitive, experiential approach of religion.[web 18] Following Schleiermacher,[106] an individual's intuition of truth was taken as the criterium for truth.[web 18] In the late 18th and early 19th century, the first translations of Hindu texts appeared, which were also read by the Transcendentalists, and influenced their thinking.[web 18] They also endorsed universalist and Unitarianist ideas, leading to Unitarian Universalism, the idea that there must be truth in other religions as well, since a loving God would redeem all living beings, not just Christians.[web 18][web 19]

Among the transcendentalists' core beliefs was the inherent goodness of both people and nature. Transcendentalists believed that society and its institutions—particularly organized religion and political parties—ultimately corrupted the purity of the individual. They had faith that people are at their best when truly "self-reliant" and independent. It is only from such real individuals that true community could be formed.

The major figures in the movement were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, Margaret Fuller and Amos Bronson Alcott.

Theosophical Society

A major force in the mutual influence of eastern and western ideas and religiosity was the Theosophical Society.[107][108] It searched for ancient wisdom in the east, spreading eastern religious ideas in the west.[109] One of its salient features was the belief in "Masters of Wisdom"[110][note 24], "beings, human or once human, who have transcended the normal frontiers of knowledge, and who make their wisdom available to others".[110] The Theosophical Society also spread western ideas in the east, aiding a modernisation of eastern traditions, and contributing to a growing nationalism in the Asian colonies.[100][note 25]

Neo-Vedanta

Neo-Vedanta, also called "neo-Hinduism"[115] and "Hindu Universalism",[web 20] is a modern interpretation of Hinduism which developed in response to western colonialism and orientalism, and aims to present Hinduism as a "homogenized ideal of Hinduism"[116] with Advaita Vedanta as its central doctrine.[117]

Unitarianism, and the idea of Universalism, was brought to India by missionaries, and had a major influence on neo-Hinduism via Ram Mohan Roy's Brahmo Samaj. Roy attempted to modernise and reform Hinduism, taking over Christian social ideas and the idea of Universalism.[79] One of the main proponents of those universalists ideas was Vivekananda,[118][119] who popularised his modernised inerpretation[120] of Advaita Vedanta in the 19th and early 20th century in both India and the west,[119] emphasising anubhava ("personal experience")[121] over scriptural authority.[121] Vivekananda played a major role in the revival of Hinduism,[122] and the spread of Advaita Vedanta to the west via the Ramakrishna Mission. His interpretation of Advaita Vedanta has been called "Neo-Vedanta".[123]

Neo-Vedanta, as represented by Vivekananda and Radhakrishnan, is indebted to Advaita vedanta, but also reflects Advaya-philosophy. Radhakrishnan acknowledged the reality and diversity of the world of experience, which he saw as grounded in and supported by the absolute or Brahman.[web 21][note 26] According to Anil Sooklal, Vivekananda's neo-Advaita "reconciles Dvaita or dualism and Advaita or non-dualism":[125]

Sankara's Vedanta is known as Advaita or non-dualism, pure and simple. Hence it is sometimes referred to as Kevala-Advaita or unqualified monism. It may also be called abstract monism in so far as Brahman, the Ultimate Reality, is, according to it, devoid of all qualities and distinctions, nirguna and nirvisesa [...] The Neo-Vedanta is also Advaitic inasmuch as it holds that Brahman, the Ultimate Reality, is one without a second, ekamevadvitiyam. But as distinguished from the traditional Advaita of Sankara, it is a synthetic Vedanta which reconciles Dvaita or dualism and Advaita or non-dualism and also other theories of reality. In this sense it may also be called concrete monism in so far as it holds that Brahman is both qualified, saguna, and qualityless, nirguna.[125]

Radhakrishnan also reinterpreted Shankara's notion of maya. According to Radhakrishnan, maya is not a strict absolute idealism, but "a subjective misperception of the world as ultimately real."[web 21] According to Sarma, standing in the tradition of Nisargadatta Maharaj, Advaitavāda means "spiritual non-dualism or absolutism",[126] in which opposites are manifestations of the Absolute, which itself is immanent and transcendent:[127]

All opposites like being and non-being, life and death, good and evil, light and darkness, gods and men, soul and nature are viewed as manifestations of the Absolute which is immanent in the universe and yet transcends it.[127]

Vivekenanda's modernisation has been criticized:

Without calling into question the right of any philosopher to interpret Advaita according to his own understanding of it, [...] the process of Westernization has obscured the core of this school of thought. The basic correlation of renunciation and Bliss has been lost sight of in the attempts to underscore the cognitive structure and the realistic structure which according to Samkaracarya should both belong to, and indeed constitute the realm of māyā.[123]

Perennial philosophy

The Perennial Philosophy sees nondualism as the essence of all religions.[citation needed] Its main proponent was Aldous Huxley, who was influenced by Vivekanda's Neo-Vedanta and Universalism.[128]

According to the Perennial Philosophy, there is an ultimate reality underlying the various religions. This ultimate reality can be called "Spirit" (Sri Aurobindo), "Brahman" (Shankara), "God", "Shunyata" (Emptiness), "The One" (Plotinus), "The Self" (Ramana Maharshi), "The Dao" (Lao Zi), "The Absolute" (Schelling) or simply "The Nondual" (F. H. Bradley).[citation needed] Ram Dass calls it the "third plane" — any phrase will be insufficient, he maintains, so any phrase will do.[citation needed]

This popular approach finds supports in the "common core-thesis". According to the "common core-thesis",[129] different descriptions can mask quite similar if not identical experiences:[130]

[P]eople can differentiate experience from interpretation, such that different interpretations may be applied to otherwise identical experiences".[130]

The "common-core thesis" is criticised by "diversity theorists" such as S.T Katz and W. Proudfoot.[130] They argue that

[N]o unmediated experience is possible, and that in the extreme, language is not simply used to interpret experience but in fact constitutes experience.[130]

New Age

The New Age movement is a Western spiritual movement that developed in the second half of the 20th century. Its central precepts have been described as "drawing on both Eastern and Western spiritual and metaphysical traditions and infusing them with influences from self-help and motivational psychology, holistic health, parapsychology, consciousness research and quantum physics".[131] The term New Age refers to the coming astrological Age of Aquarius.[web 22]

The New Age aims to create "a spirituality without borders or confining dogmas" that is inclusive and pluralistic.[132] It holds to "a holistic worldview",[133] emphasising that the Mind, Body and Spirit are interrelated[134] and that there is a form of monism and unity throughout the universe.[web 23] It attempts to create "a worldview that includes both science and spirituality"[135] and embraces a number of forms of mainstream science as well as other forms of science that are considered fringe.[citation needed]

Neo-Advaita

Neo-Advaita is a New Religious Movement based on a modern, western interpretation of Advaita Vedanta, especially the teachings of Ramana Maharshi.[136] Neo-Advaita is being criticized[137][note 27][139][note 28][note 29] for discarding the traditional prerequisites of knowledge of the scriptures[141] and "renunciation as necessary preparation for the path of jnana-yoga".[141][142] Notable neo-advaita teachers are H. W. L. Poonja,[143][136] his students Gangaji[144] Andrew Cohen[note 30], and Eckhart Tolle.[136]

Perceived similarities

Hinduism

Advaita Vedanta

Georg Feuerstein is quoted by nondualists[note 31] as summarizing the Advaita Vedanta-realization as follows:

The manifold universe is, in truth, a Single Reality. There is only one Great Being, which the sages call Brahman, in which all the countless forms of existence reside. That Great Being is utter Consciousness, and It is the very Essence, or Self (Atman) of all beings."[web 30]

The quote seems to give a subtle reinterpretation, in which the distinction between Real and maya is replaced by a notion of interconnectedness or pantheism. This approach has also been criticized:

These definitions are different from Advaita Vedanta, which sees both object and subject as Maya, illusion.[20]

Yoga

Yoga is a commonly known generic term for physical, mental, and spiritual disciplines which originated in ancient India.[146][147] Specifically, yoga is one of the six āstika ("orthodox") schools of Hindu philosophy. One of the most detailed and thorough expositions on the subject are the Yoga Sūtras of Patañjali. Various traditions of yoga are found in Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism.[148][149][150]

Samkhya and dualism

Yoga is traditionally closely associated with Samkhya, which is strongly dualistic[151][152][153] Sāmkhya philosophy regards the universe as consisting of two realities; Puruṣa (consciousness) and prakriti (phenomenal realm of matter). Jiva is that state in which puruṣa is bonded to prakriti through the glue of desire, and the end of this bondage is moksha. Samkhya does not describe what happens after moksha and does not mention anything about Ishwara or God, because after liberation there is no essential distinction of individual and universal puruṣa.[154][155]

Non-dualism in Yoga

Whicher challenges the "dualistic" historical paradigm of Yoga scholarship founded in a separation of "puruṣa" and "prakṛti" thus:

It is often said [by Western scholarship] that, like classical Sāṃkha, Patañjali's yoga is a dualistic system, understood in terms of puruṣa and prakṛti. Yet, I submit, yoga scholarship has not clarified what "dualistic" means or why yoga had to be "dualistic". Even in avowedly non-dualistic systems of thought such as Advaita Vedanta we can find numerous examples of basically dualistic modes of description and explanation."[156]

According to Swami Rājarshi, the historical synthesis of the School of Yoga introduces the principle of Saguna Brahman as "Isvara", controller or God, to reconcile "the transcendental, nondual monism of vedanta and the pluralistic, dualistic, atheism of sankhya". Vedanta is "advandva", "nonduality of the highest truth at the transcendental level".[157] Samkhya is "dvandva", "duality or pairs of opposites".[157] According to Swami Rājarshi, "sankhya presents truth of the same reality but at a lower empirical level, rationally analyzing the principle of dvandva.[157] Yoga philosophy "presents the synthesis of vedanta and sankhya, reconciling at once monism and dualism, the supermundane and the empirical".[157]

Shaivism

Kashmir Shaivism

Kashmir Shaivism is a school of Śaivism consisting of Trika, the three goddesses Parā, Parāparā and Aparā, and its philosophical articulation in Pratyabhijña, a branch of Kashmir Shaivism.[158] It is described by Abhinavagupta[note 32]as "paradvaita", meaning "the supreme and absolute non-dualism".[web 31]

It is categorized by various scholars as monistic[159] idealism (absolute idealism, theistic monism,[160] realistic idealism,[161] transcendental physicalism or concrete monism.[161])

The philosophy of Kashmir Shaivism can be seen in contrast to Shankara's Advaita.[162] Advaita Vedanta holds that Brahman is inactive (niṣkriya) and the phenomenal world is an illusion (māyā). In Kashmir Shavisim, all things are a manifestation of the Universal Consciousness, Chit or Brahman.[163][164] Kashmir Shavisim sees the phenomenal world (Śakti) as real: it exists, and has its being in Consciousness (Chit).[165]

Anuttara is the ultimate principle in Kashmir Shaivism. It is the fundamental reality underneath the whole Universe. Among the multiple interpretations of anuttara are: "supreme", "above all" and "unsurpassed reality".[166] In the Sanskrit alphabet anuttara is associated to the first letter - "A" (in devanagari "अ"). As the ultimate principle, anuttara is identified with Śiva, Śakti (as Śakti is identical to Śiva), the supreme consciousness (cit), uncreated light (prakāśa), supreme subject (aham) and atemporal vibration (spanda).

The goal of Kashmir Shaivism is to merge in Shiva or Universal Consciousness, or realise one's already existing identity with Shiva, by means of wisdom, yoga and grace.[167][168] The practitioner who realizes anuttara through any means, whether by her own efforts or by direct transmission by the Grace of Shiva/shakti, is liberated and perceives absolutely no difference between herself and the body of the universe. Being and beings become one and the same by virtue of the "erotic friction," whereby subject perceives object and in that act of perception is filled with nondual being/consciousness/bliss. Anuttara is different from the notion of transcendence in that, even though it is above all, it does not imply a state of separation from the Universe.[169]

Ramana Maharshi

Ramana Maharshi (30 December 1879 – 14 April 1950) is widely acknowledged as one of the outstanding Indian gurus of modern times.[170] Ramana's teachings are often interpreted as Advaita Vedanta, though Ramana Maharshi never "received diksha (initiation) from any recognised authority".[web 32] Ramana himself did not call his insights advaita:

D. Does Sri Bhagavan advocate advaita?

M. Dvaita and advaita are relative terms. They are based on the sense of duality. the Self is as it is. There is neither dvaita nor advaita. "I Am that I Am."[note 33] Simple Being is the Self.[172]

Throughout his life, through contact with educated devotees like Ganapata Muni,[173] Ramana Maharshi became acquainted with works on Shaivism and Advaita Vedanta, and used them to explain his insights:[174]

People wonder how I speak of Bhagavad Gita, etc. It is due to hearsay. I have not read the Gita nor waded through commentaries for its meaning. When I hear a sloka (verse), I think its meaning is clear and I say it. That is all and nothing more.[175]

Though Ramana's teachings are often considered to be akin to Vedanta, his spiritual life is also associated with Shaivism.[note 34] In contrast to Shankara's Vedanta, which speaks of Maya and sees "this world as a trap and an illusion, Shaivism says it is the embodiment of the Divine".[177] It speaks of "the Goddess Shakti, or spiritual energy, portrayed as the Divine Mother who redeems the material world".[177]

Natha Sampradaya and Inchegeri Sampradaya

The Natha Sampradaya, with Nath yogis such as Gorakhnath, introduced Sahaja, the concept of a spontaneous spirituality. Sahaja means "spontaneous, natural, simple, or easy"[web 35]

The Inchegeri Sampradaya of Siddharameshwar Maharaj and Nisargadatta Maharaj belongs to the Nath-tradition. Siddharameshwar Maharaj calls turiya the "Great-Causal Body",[178] and counts it as the fourth body. He describes his method of self-enquiry, in which the three bodies are recognized as "empty" of an essence or the sense of "I am".[179][note 35] This knowledge resides in the fourth body or turiya,[92] and cannot be described.[179][note 36] It is Turiya, the state before Ignorance and Knowledge.[178]

Buddhism

Buddhism is a continuum of a number of sub-traditions and praxis-lineages (or sadhana-lineages), in various sub-traditions and vehicles (Sanskrit: yana)[181][note 37]

Madhyamaka

According to Huntington and Wangchen, the actualization of emptiness is non-dualistic:

With the actualization of emptiness, manifest in wisdom as an effect, the bodhisattva gains access to the nondualistic knowledge of a buddha.[183]

According to Herbert Guenther and Chögyam Trungpa, the realization of the "Pure-and-perfect-Mind"[note 38] "has gone beyond the dualism of subject and object":[184]

We cannot predicate anything of prajna except to say that when it is properly prajna it must be as open as that which it perceives. In this sense we might say that subjective and objective poles, (prajna and shunyata) coincide. With this understanding, rather than saying that prajna is shunyata, we can try to describe the experience by saying that it has gone beyond the dualism of subject and object.[184]

Buddha-nature

The Buddhist teachings on the Buddha-nature may be regarded as a form of nondualism.[185] Buddha-nature is the essential element that allows sentient beings to become Buddhas.[186] The term, Buddha nature, is a translation of the Sanskrit coinage, 'Buddha-dhātu', which seems first to have appeared in the Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra,[187] where it refers to 'a sacred nature that is the basis for [beings'] becoming buddhas.'[188] The term seems to have been used most frequently to translate the Sanskrit "Tathāgatagarbha". The Sanskrit term "tathāgatagarbha" may be parsed into tathāgata ("the one thus gone", referring to the Buddha) and garbha ("womb").[note 39] The tathagatagarbha, when freed from avidya ("ignorance"), is the dharmakaya, the Absolute.

The Śrīmālādevī Sūtra (3rd century CE[189]), also named The Lion's Roar of Queen Srimala, centers on the teaching of the tathagatagarbha as "ultimate soteriological principle".[190] Regarding the tathagata-garbha it states:

Lord, the Tathagatagarbha is neither self nor sentient being, nor soul, nor personality. The Tathagatagarbha is not the domain of beings who fall into the belief in a real personality, who adhere to wayward views, whose thoughts are distracted by voidness. Lord, this Tathagatagarbha is the embryo of the Illustrious Dharmadhatu, the embryo of the Dharmakaya, the embryo of the supramundane dharma, the embryo of the intrinsically pure dharma.[191]

In the Śrīmālādevī Sūtra, there are two possible states for the Tathagatagarbha:

[E]ither covered by defilements, when it is called only "embryo of the Tathagata"; or free from defilements, when the "embryo of the Tathagata" is no more the "embryo" (potentiality) but the Tathagata (actuality).[192]

The sutra itself states it this way:

This Dharmakaya of the Tathagata when not free from the store of defilement is referred to as the Tathagatagarbha.[193]

Zen

Kensho

The Buddha-nature philosophy has had a strong influence on Chán and Zen. The continuous pondering of the break-through kōan (shokan[194]) or Hua Tou, "word head",[195] leads to kensho, an initial insight into "seeing the (Buddha-)nature.[196]

According to Hori, a central theme of many koans is the 'identity of opposites':[197][198]

[K]oan after koan explores the theme of nonduality. Hakuin's well-known koan, "Two hands clap and there is a sound, what is the sound of one hand?" is clearly about two and one. The koan asks, you know what duality is, now what is nonduality? In "What is your original face before your mother and father were born?" the phrase "father and mother" alludes to duality. This is obvious to someone versed in the Chinese tradition, where so much philosophical thought is presented in the imagery of paired opposites. The phrase "your original face" alludes to the original nonduality.[197]

Comparable statements are: "Look at the flower and the flower also looks"; "Guest and host interchange".[199]

The aim of the break-through koan is to see the "nonduality of subject and object":[197][198]

The monk himself in his seeking is the koan. Realization of this is the insight; the response to the koan [...] Subject and object - this is two hands clapping. When the monk realizes that the koan is not merely an object of consciousness but is also he himself as the activity of seeking an answer to the koan, then subject and object are no longer separate and distinct [...] This is one hand clapping.[200]

Victor Sogen Hori describes kensho, when attained through koan-study, as the absence of subject-object duality:

awakening occurs at the breakdown of the subject-object distinction expressed in "seeing" (subject of experience) and "one's nature" (object of experience) [...] In koan training, the insight comes precisely in the fact that the traditional distinction between a subject of consciousness and an object of consciousness ("two hands clapping") has broken down. The subject seeing and the object seen are not independent and different. "One's nature" and "seeing" are not two. To realize, in both senses of "realize," this fundamental non-duality is the point of koan practice and what makes it mystical insight. One gets to this fundamental realization not through the rational understanding of a conceptual truth, but through the constant repetition of the koan. One merely repeats the koan without being given any instruction on why or how. Ritual formalism leads to mystical insight.[201]

Various accounts can be found which describe this "becoming one" and the resulting breakthrough:

I was dead tired. That evening when I tried to settle down to sleep, the instant I laid my head on the pillow, I saw: "Ah, this outbreath is Mu!" Then: the in-breath too is Mu!" Next breath, too: Mu! Nex breath: Mu, Mu! "Mu, a whole sequence of Mu! Croak, croak; meow, meow - these too are Mu! The bedding, the waal, the column, the sliding-door - these too are Mu! This, that and everything is Mu! Ha ha! Ha ha ha ha Ha! that roshi is a rascal! He's always tricking people with his 'Mu, Mu, Mu'!...[202][note 40]

Post-satori practice

Zen Buddhist training does not end with kenshō. Practice is to be continued to deepen the insight and to express it in daily life,[204][205][206][207] to fully manifest the nonduality of absolute and relative. According to the contemporary Chan Master Sheng Yen:

Ch'an expressions refer to enlightenment as "seeing your self-nature". But even this is not enough. After seeing your self-nature, you need to deepen your experience even further and bring it into maturation. You should have enlightenment experience again and again and support them with continuous practice. Even though Ch'an says that at the time of enlightenment, your outlook is the same as of the Buddha, you are not yet a full Buddha.[208]

And the contemporary western Rev. Master Jiyu-Kennett:

One can easily get the impression that realization, kenshō, an experience of enlightenment, or however you wish to phrase it, is the end of Zen training. It is not. It is, rather, a new beginning, an entrance into a more mature phase of Buddhist training. To take it as an ending, and to "dine out" on such an experience without doing the training that will deepen and extend it, is one of the greatest tragedies of which I know. There must be continuous development, otherwise you will be as a wooden statue sitting upon a plinth to be dusted, and the life of Buddha will not increase.[209]

To deepen the initial insight of kensho, shikantaza and kōan-study are necessary. This trajectory of initial insight followed by a gradual deepening and ripening is expressed by Linji Yixuan in his Three mysterious Gates, the Four Ways of Knowing of Hakuin,[210] the Five Ranks, and the Ten Ox-Herding Pictures[211] which detail the steps on the Path.

Vajrayana Buddhism

Vajrayana, primarily found in Tibet, but also existing in other Southeast Asian countries, is the Buddhist variant of Tantra.

Dzogchen tradition

Dzogchen is a relatively esoteric (to date) tradition concerned with the "natural state", and emphasizing direct experience. This tradition is found in the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, where it is classified as the highest of this lineage's nine yanas, or vehicles of practice. Similar teachings are also found in the non-Buddhist Bön tradition, where it is also given the nomenclature "Dzogchen" and in one evocation the ninth in a nine vehicle system. The nine vehicles in both the Bonpo and Buddhadharma traditions are different but they mutually inform. In Dzogchen, for both the Bonpo and Nyingmapa, the primordial state, the state of nondual awareness, is called rigpa.[citation needed]

The Dzogchen practitioner realizes that appearance and emptiness are inseparable. One must transcend dualistic thoughts to perceive the true nature of one's pure mind. This primordial nature is clear light, unproduced and unchanging, free from all defilements. One's ordinary mind is caught up in dualistic conceptions, but the pure mind is unafflicted by delusions. Through meditation, the Dzogchen practitioner experiences that thoughts have no substance. Mental phenomena arise and fall in the mind, but fundamentally they are empty. The practitioner then considers where the mind itself resides. The mind can not exist in the ever-changing external phenomena and through careful examination one realizes that the mind is emptiness. All dualistic conceptions disappear with this understanding.[212]

Svabhava (Sanskrit; Wylie: rang bzhin) is very important in the nontheistic theology of the Bonpo Dzogchen 'Great Perfection' tradition where it is part of a technical language to acknowledges the ontological identity of macrocosm and microcosm :

The View of the Great Perfection further acknowledges the ontological identity of the macrocosmic and microcosmic realities through the threefold axiom of Condition (ngang), Ultimate Nature (rang bzhin) and Identity (bdag nyid) [...] The non-duality between the Ultimate Nature (i.e., the unaltered appearance of all phenomena) and the Condition (i.e., the Basis of all [kun gzhi]) is called the Identity (bdag nyid). This unicum of primordial purity (ka dag) and spontaneous accomplishment (lhun grub) is the Way of Being (gnas lugs) of the Pure-and-Perfect-Mind [byang chub (kyi) sems].[213]

Ngakpa tradition

Ngakpa Chögyam, a Tibetan Buddhist teacher from Wales, explains that nonduality, or emptiness, has two facets:

[O]ne is the empty, or nondual, and the other is form, or duality. Therefore, duality is not illusory but is instead one aspect of nonduality. Like the two sides of a coin, the formless reality has two dimensions – one is form, the other is formless. When we perceive duality as separate from nonduality (or nonduality as separate from duality), we do not engage the world of manifestation from a perspective of oneness, and thereby we fall into an erroneous relationship with it. From this perspective it is not "life" or duality that is maya, or illusion; rather, it is our relationship to the world that is illusory."[214]

Sikhism

Sikhism is a monotheistic religion which holds the view of non-dualism.[citation needed] A principal cause of suffering in Sikhism is the ego (ahankar in Punjabi), the delusion of identifying oneself as an individual separate from the surroundings. From the ego arises the desires, pride, emotional attachments, anger, lust, etc., thus putting humans on the path of destruction. According to Sikhism, the true nature of all humans is the same as God, and everything that originates with God. The goal of a Sikh is to conquer the ego and realize one's true nature or self, which is the same as God's.

The gurmukh

[N]o longer represents the Absolute to himself, because the distinction between self and other, I and not-I disappears into a knowing that knows without immediately splitting into subject and object.[215]

Taoism

Dechar speculates that the terms "Tao" and "Dharma" are etymologically related by the etymon "da":

The Chinese word Tao has an etymological relationship to the Sanskrit root sound "da", which means "to divide something whole into parts". The ancient Sanskrit word dharma is also related to this root. In the Buddhist tradition, dharma means "that which is to be held fast, kept, an ordinance or law [...] the absolute, the real." So, both dharma and Tao refer to the way that the One, the unfathomable unity of the divine, divides into parts and manifests in the world of form.[216][note 41]

Taoism's wu wei (Chinese wu, not; wei, doing) is a term with various translations[note 42] and interpretations designed to distinguish it from passivity. The concept of Yin and Yang, often mistakenly conceived of as a symbol of dualism, is actually meant to convey the notion that all apparent opposites are complementary parts of a non-dual whole.[217]

Subud

Subud is a spiritual movement that began in Java, Indonesia in the 1920s as a movement founded by Muhammad Subuh Sumohadiwidjojo.[note 43] Java has been a melting pot of religions and cultures, which has created a broad range of religious belief. Muhammad Subuh claimed that Subud is not a new teaching or religion but only that the latihan kejiwaan itself is the kind of proof that humanity is looking for. Pak Subuh gives the following descriptions of Subud:[218]

This is the symbol of a person who has a calm and peaceful inner feeling and who is able to receive the contact with the Great Holy Life Force.[218]

The name "Subud" is an acronym that stands for three Javanese words, Susila Budhi Dharma, which are derived from the Sanskrit terms suzila, bodhi and dharma.[219] Pak Subuh gives the following definitions:[218]

- Susila: the good character of man in accordance with the Will of Almighty God

- Budhi: the force of the inner self within man

- Dharma: surrender, trust and sincerity towards Almighty God

The basis of Subud is a spiritual exercise commonly referred to as the latihan kejiwaan, the guidance from "the Power of God" or "the Great Life Force". The latihan is a vivid encounter which is fresh, alive and personal. It evolves and deepens over time.

Middle-eastern religions

Jewish traditions and Hasidism

According to Michaelson, nonduality begins to appear in the medieval Jewish textual tradition which peaked in Hasidism:

As a Jewish religious notion, nonduality begins to appear unambigously in Jewish texts during the medieval period, increasing in frequency in the centuries thereafter and peaking at the turn of the nineteenth century, with the advent of Hasidism. It is certainly possible that earlier Jewish texts may suggest nonduality – as, of course, they have been interpreted by traditional nondualists – but...this may or may not be the most useful way to approach them."[220]

Michaelson explores nonduality in the tradition of Judaism:

Judaism has within it a strong and very ancient mystical tradition that is deeply nondualistic. "Ein Sof" or infinite nothingness is considered the ground face of all that is. God is considered beyond all proposition or preconception. The physical world is seen as emanating from the nothingness as the many faces "partsufim" of god that are all a part of the sacred nothingness.[221]

Christianity

The Cloud of Unknowing an anonymous work of Christian mysticism written in Middle English in the latter half of the 14th century advocates a mystic relationship with God. The text describes a spiritual union with God through the heart. The author of the text advocates centering prayer, a form of inner silence. According to the text God can not be known through knowledge or from intellection. It is only by emptying the mind of all created images and thoughts that we can arrive to experience God. According to the text God is completely unknowable by the mind. God is not known through the intellect but through intense contemplation, motivated by love, and stripped of all thought.[222]

Christian Science has been described as nondual. In a glossary of terms written by the founder, Mary Baker Eddy, matter is defined as illusion, and when defining 'I, or Ego' as the divine in relationship with individual identity, she writes "There is but one I, or Us, but one divine Principle, or Mind, governing all existence" – continuing – ". . .whatever reflects not this one Mind, is false and erroneous, even the belief that life, substance, and intelligence are both mental and material."[223]

Griffiths' (1906–1993) form of Vedanta-inspired or nondual Christianity, coming from the Christian Ashram Movement, has inspired papers by Bruno Barnhart discussing 'Wisdom Christianity' or 'Sapiential Christianity'.[224][225] Barnhart (1999: p. 238) explores Christian nondual experience in a dedicated volume and states that he gives it the gloss of "unitive" experience and "perennial philosophy".[226] Further, Barnhart (2009) holds that:

It is quite possible that nonduality will emerge as the theological principle of a rebirth of sapiential Christianity ('wisdom Christianity') in our time."[225]

Several prominent members of the Sanbo Kyodan are Catholic priests, such as Hugo Enomiya-Lassalle and AMA Samy. D.T Suzuki saw commonalities between Zen and Christian mysticism.[227]

Eastern contemplative techniques have been integrated in Christian practices, such as centering prayer.[web 36] But this integration has also raised questions about the borders between these traditions.[web 37]

According to the teachings of The Infinite Way, God is a non-dual experience.[citation needed] Joel Goldsmith wrote that thought and ideas in the mind take people away from the realization of God. To experience God, he recommended meditation and for the subject to tune into the present moment so duality of the subject disappears.[citation needed]

The former nun and contemplative Bernadette Roberts is considered a nondualist by Jerry Katz.[21]

Thomism, though not non-dual in the ordinary sense, considers the unity of God so absolute that even the duality of subject and predicate, to describe him, can be true only by analogy. In Thomist thought, even the Tetragrammaton is only an approximate name, since "I am" involves a predicate whose own essence is its subject.[228]

Gnosticism

Since its beginning, Gnosticism has been characterized by many dualisms and dualities, including the doctrine of a separate God and Manichaean (good/evil) dualism.

Ronald Miller interprets the Gospel of Thomas as a teaching of "nondualistic consciousness".[229]

Islam

Sufism and Irfan (Arabic تصوف taṣawwuf) are the mystical traditions of Islam. There are a number of different Sufi orders that follow the teachings of particular spiritual masters, but the bond that unites all Sufis is the concept of ego annihilation through various spiritual exercises and a persistent, ever-increasing longing for union with the divine.[230] Reza Aslan has written:

Like most mystics, Sufis strive to eliminate the dichotomy between subject and object in their worship. The goal is to create an inseparable union between the individual and the Divine.[231]

The central doctrine of Sufism, sometimes called Wahdat-ul-Wujood or Wahdat al-Wujud or Unity of Being, is the Sufi understanding of Tawhid (the oneness of God; absolute monotheism).[232] Put very simply, for Sufis, Tawhid implies that all phenomena are manifestations of a single reality, or Wujud (being), which is indeed al-Haq (Truth, God). The essence of Being/Truth/God is devoid of every form and quality, and hence unmanifest, yet it is inseparable from every form and phenomenon, either material or spiritual. It is often understood to imply that every phenomenon is an aspect of Truth and at the same time attribution of existence to it is false. The chief aim of all Sufis then is to let go of all notions of duality (and therefore of the individual self also), and realize the divine unity which is considered to be the truth.

Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi, (1207–1273), one of the most famous Sufi masters and poets, has written that what humans perceive as duality is in fact a veil, masking the reality of the Oneness of existence:

All desires, preferences, affections, and loves people have for all sorts of things [are veils] [...] When one passes beyond this world and sees that Sovereign (God) without these 'veils,' then one will realize that all those things were 'veils' and 'coverings' and that what they were seeking was in reality that One.[233]

Western philosophy

Neo-platonism

Scholar Jay Michaelson identifies the origins of non-dualism proper founded in the Neoplatonism of Plotinus within Ancient Greece, and employs the ambiguous binary construction of "the West":[note 44]

Conceptions of nonduality evolve historically. As a philosophical notion, it is most clearly found for the first time in the West in the second century C.E, in the Neoplatonism of Plotinus and his followers."[220]

Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Ananda Coomaraswamy used the writing of Plotinus in their own texts as a superlative elaboration upon Indian monism, specifically Upanishadic and Advaita Vedantic thought.[citation needed] Ananda Coomaraswamy has compared Plotinus' teachings to the Hindu school of Advaita Vedanta (advaita meaning "not two" or "non-dual"),[234]

Advaita Vedanta and Neoplatonism have been compared by J. F. Staal,[235] Frederick Copleston,[236] Aldo Magris and Mario Piantelli,[237] Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan,[238] Gwen Griffith-Dickson,[239] and John Y. Fenton.[240]

The joint influence of Advaitin and Neoplatonic ideas on Ralph Waldo Emerson is considered by Dale Riepe.[241]

Process philosophy

Process philosophy, and especially Alfred North Whitehead's blend, has sought to develop a worldview that avoids ontological dualism but still provides a distinction between body, mind and soul. [242]

Popular western understanding

Transpersonal psychology

Theriault (2005) in a thesis explores comparative non-dual experience and the psycho-spiritual mechanisms that bring this awareness about.[243]

Lewis (2007) in her thesis explores a number of specific women's experiences on their journey to wholeness and healthfulness in the nondual path of Tantra post-sexual trauma and identifies common themes.[244]

A Course in Miracles

A Course in Miracles is an expression of nondualism that is independent of any religious denomination. For instance in a workshop entitled 'The Real World' led by two of its more prominent teachers, Kenneth Wapnick and Gloria Wapnick, Gloria explains how discordant the course is from the teachings of Christianity:

"The course is very clear in that God did not create the physical world or universe - or anything physical. It parts ways right at the beginning. If you start with the theology of the course, there's nowhere you can reconcile from the beginning, because the first book of Genesis talks about God creating the world, and then the animals and humans, et cetera. The course parts company at page one with the Bible."[245]

A Course in Miracles presents an interpretation of nondualism that recognises only "God" (i.e. absolute reality) as existing in any way, and nothing else existing at all. In a book entitled The Disappearance of the Universe, which explains and elaborates on A Course in Miracles, it says in its second chapter that we "don't even exist in an individual way - not on any level. There is no separated or individual soul. There is no Atman, as the Hindus call it, except as a mis-thought in the mind. There is only God."[246] A verse from the course itself that displays its interpretation of nondualism is found in Chapter 14:

"The first in time means nothing, but the First in eternity is God the Father, Who is both First and One. Beyond the First there is no other, for there is no order, no second or third, and nothing but the First."[247]

Criticism

The idea of a common essence is objected by Yandell, who discerns various "religious experiences" and their corresponding doctrinal settings, which differ in structure and phenomenological content, and in the "evidential value" they present.[248] Yandell discerns five sorts:[249]

- Numinous experiences - Monotheism (Jewish, Christian, Vedantic)[250]

- Nirvanic experiences - Buddhism,[251] "according to which one sees that the self is but a bundle of fleeting states"[252]

- Kevala experiences[253] - Jainism,[254] "according to which one sees the self as an undestructible subject of experience"[254]

- Moksha experiences[255] - Hinduism,[254] Brahman "either as a cosmic person, or, quite differently, as qualityless"[254]

- Nature mystical experience[253]

See also

Various

- Abheda

- Acosmism (belief that the world is illusory)

- Anatta (Belief that there is no self)

- Dualism

- Emanationism

- Henosis (Union with the absolute)

- Kenosis (Self-emptying)

- Maya (illusion) (Cosmic illusion)

- Monad (philosophy)

- Neo-Advaita

- Nihilism

- Open individualism

- Panentheism

- Pantheism (Belief that God and the world are identical)

- Pluralism (metaphysics)

- Process Psychology

- Rigpa

- Shuddhadvaita

- Sunyata (Emptiness).

- The All

- Turiya

- Yanantin (Complementary dualism in Native South American culture)

Metaphors for nondualisms

- Jewel Net of Indra, Avatamsaka Sutra

- Blind men and an elephant

- Eclipse[256]

- Hermaphrodite, e.g. Ardhanārīśvara

- Mirror and reflections, as a metaphor for the continuum of the subject-object in the mirror-the-mind and the interiority of perception and its illusion of projected exteriority

- Great Rite

- Sacred marriage

Notes

- ^ Called turiya and sahaja in Hinduism, and luminous mind, Buddha-nature and rigpa (among other terms) in Buddhism.

- ^ Loy distinguishes even "Five Flavors Of Nonduality":[web 3]

- The negation of dualistic thinking in pairs of opposites. The Yin-Yang symbol of Taoism symbolises the transcendence of this dualistic way of thinking.[web 3]

- The nonplurality of the world. Although the phenomenal world appears as a pluarality of "things", in reality they are "of a single cloth".[web 3]

- The nondifference of subject and object, or nonduality between subject and object.[web 3]

- The identity of phenomena and the Absolute, the "nonduality of duality and nonduality".[web 3]

- A mystical unity between God and man.[web 3]

- ^ The distinction is made by T.R.V. Murti in his "The Central Phiosophy", and referenced to by Nunen[8] and Davis.[4]

- ^ Sunyata can also be referred to as "anutpada" (Buddhism), or Ajativada, meaning unborn, without origin.[11][12] The term is also used in the Lankavatara Sutra.[13] According to D.T Suzuki, "anutpada" is not the opposite of "utpada", but transcends opposites. It is the seeing into the true nature of existence,[14] the seeing that "all objects are without self-substance".[15]

- ^ Kalupahana: "Two aspects of the Buddha's teachings, the philosophical and the practical, which are mutually dependent, are clearly enunciated in two discourses, the Kaccaayanagotta-sutta and the Dhammacakkappavattana-sutta, both of which are held in high esteem by almost all schools of Buddhism in spite of their sectarian rivalries. The Kaccaayanagotta-sutta, quoted by almost all the major schools of Buddhism, deals with the philosophical "middle path", placed against the backdrop of two absolutistic theories in Indian philosophy, namely, permanent existence (atthitaa) propounded in the early Upanishads and nihilistic non-existence (natthitaa) suggested by the Materialists."

- ^ Vijnana can be translated as "consciousness", "life force", "mind"[16] or "discernment".[17][18]

- ^ See also essence and function and Absolute-relative on Chinese Chán

- ^ According to Loy, nondualism is primarily an Eastern way of understanding: "...[the seed of nonduality] however often sown, has never found fertile soil [in the West], because it has been too antithetical to those other vigorous sprouts that have grown into modern science and technology. In the Eastern tradition [...] we encounter a different situation. There the seeds of seer-seen nonduality not only sprouted but matured into a variety (some might say a jungle) of impressive philosophical species. By no means do all these [Eastern] systems assert the nonduality of subject and object, but it is significant that three which do – Buddhism, Vedanta and Taoism – have probably been the most influential.[22]

- ^ 'Own-beings',[43] unique nature or substance,[44] an identifying characteristic; an identity; an essence,[45]

- ^ A differentiating characteristic,[45] the fact of being dependent,[45]

- ^ 'Being',[46] 'self-nature or substance'[47]

- ^ Not being present; absence[48]

- ^ Warder: "From Nagarjuna's own day onwards his doctrine was subject to being misunderstood as nihilistic: because he rejected 'existence' of beings and spoke of their 'emptiness' (of own-being) careless students (and critics who were either not very careful or not very scrupulous) have concluded that he maintained that ultimately the universe was an utter nothingness. In fact his rejection of 'non-existence' is as emphatic as his rejection of 'existence', and must lead us to the conclusion that what he is attacking is these notions as metaphysical concepts imposed on the real universe.[51]

- ^ It is often used interchangeably with the term citta-mātra, but they have different meanings. The standard translation of both terms is "consciousness-only" or "mind-only." Several modern researchers object this translation, and the accompanying label of "absolute idealism" or "idealistic monism".[57] A better translation for vijñapti-mātra is representation-only.[58]

- ^ 1. Something is. 2. It is not. 3. It both is and is not. 4. It neither is nor is not.[web 5][81]

- ^ The influence of Mahayana Buddhism on other religions and philosophies was not limited to Vedanta. Kalupahana notes that the Visuddhimagga contains "some metaphysical speculations, such as those of the Sarvastivadins, the Sautrantikas, and even the Yogacarins".[83]

- ^ "An" means "not", or "non"; "utpāda" means "genesis", "coming forth", "birth"[web 6] Taken together "anutpāda" means "having no origin", "not coming into existence", "not taking effect", "non-production".[web 7] The Buddhist tradition usually uses the term "anutpāda" for the absence of an origin[11][84] or sunyata.[85] The term is also used in the Lankavatara Sutra.[13] According to D.T Suzuki, "anutpada" is not the opposite of "utpada", but transcends opposites. It is the seeing into the true nature of existence,[14] the seeing that "all objects are without self-substance".[15]

- ^ "A" means "not", or "non" as in Ahimsa, non-harm; "jāti" means "creation" or "origination;[86] "vāda" means "doctrine"[86]

- ^ In Dutch: "Niet in een denkbeeld te vatten".[95]

- ^ According to Renard, Alan Watts has explained the difference between "non-dualism" and "monism" in The Supreme Identity, Faber and Faber 1950, p.69 and 95; The Way of Zen, Pelican-edition 1976, p.59-60.[99]

- ^ See McMahan, "The making of Buddhist modernity"[100] and Richard E. King, "Orientalism and Religion"[79] for descriptions of this mutual exchange.

- ^ The awareness of historical precedents seems to be lacking in nonduality-adherents, just as the subjective perception of parallels between a wide variety of religious traditions lacks a rigorous philosophical or theoretical underpinning.

- ^ And called his poodle "Atman".[104]

- ^ See also Ascended Master Teachings

- ^ The Theosophical Society had a major influence on Buddhist modernism[100] and Hindu reform movements,[108] and the spread of those modernised versions in the west.[100] The Theosophical Society and the Arya Samaj were united from 1878 to 1882, as the Theosophical Society of the Arya Samaj.[111] Along with H. S. Olcott and Anagarika Dharmapala, Blavatsky was instrumental in the Western transmission and revival of Theravada Buddhism.[112][113][114]

- ^ Neo-Vedanta seems to be closer to Bhedabheda-Vedanta than to Shankara's Advaita Vedanta, with the acknowledgement of the reality of the world. Nicholas F. Gier: "Ramakrsna, Svami Vivekananda, and Aurobindo (I also include M.K. Gandhi) have been labeled "neo-Vedantists," a philosophy that rejects the Advaitins' claim that the world is illusory. Aurobindo, in his The Life Divine, declares that he has moved from Sankara's "universal illusionism" to his own "universal realism" (2005: 432), defined as metaphysical realism in the European philosophical sense of the term."[124]

- ^ Marek: "Wobei der Begriff Neo-Advaita darauf hinweist, dass sich die traditionelle Advaita von dieser Strömung zunehmend distanziert, da sie die Bedeutung der übenden Vorbereitung nach wie vor als unumgänglich ansieht. (The term Neo-Advaita indicating that the traditional Advaita increasingly distances itself from this movement, as they regard preparational practicing still as inevitable)[138]

- ^ Alan Jacobs: Many firm devotees of Sri Ramana Maharshi now rightly term this western phenomenon as 'Neo-Advaita'. The term is carefully selected because 'neo' means 'a new or revived form'. And this new form is not the Classical Advaita which we understand to have been taught by both of the Great Self Realised Sages, Adi Shankara and Ramana Maharshi. It can even be termed 'pseudo' because, by presenting the teaching in a highly attenuated form, it might be described as purporting to be Advaita, but not in effect actually being so, in the fullest sense of the word. In this watering down of the essential truths in a palatable style made acceptable and attractive to the contemporary western mind, their teaching is misleading.[140]

- ^ See for other examples Conway [web 24] and Swartz [web 25]

- ^ Presently cohen has distnced himself from Poonja, and calls his teachings "Evolutionary Enlightenment".[145] What Is Enlightenment, the magazine published by Choen's organisation, has been critical of neo-Advaita several times, as early as 2001. See.[web 26][web 27][web 28]

- ^ Feuerstein's summary, as given here, is not necessarily representative for Feuerstein's thought on Advaita. It is quoted on nonduality-websites.[web 29] The original quote is from Feuerstein's book "The Deeper Dimension of Yoga: Theory and Practice", p.257-258. It is preceded by the sentence "The esoteric teaching of nonduality - Vedantic Yoga or Jnana Yoga - can be summarized as follows".

- ^ Abhinavgupta (between 10th – 11th century AD) who summarized the view points of all previous thinkers and presented the philosophy in a logical way along with his own thoughts in his treatise Tantraloka.[web 31]

- ^ A Christian reference.See [web 33] and.[web 34] Ramana was taught at Christian schools.[171]

- ^ Shankara himself was said to be a shaivite, or even a reincarnation of Shiva.[176]

- ^ Siddharameshwar Maharaj's method closely parallels Buddhist methods of enquiry into the nature of self, as reflected in the Milinda Panha.

- ^ According to Nisargadatta Maharaj too, what this "I am" is cannot be described or defined; the only thing to be stated about it is what it is not.[180]