Nonsteroidal antiandrogen

| Nonsteroidal antiandrogen | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

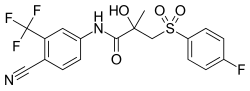

Bicalutamide, the most widely used nonsteroidal antiandrogen and the most widely used antiandrogen in prostate cancer. | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Synonyms | Nonsteroidal androgen receptor antagonists |

| Use | Prostate cancer; Acne; Hirsutism; Seborrhea; Pattern hair loss; Hyperandrogenism; Transgender hormone therapy; Male precocious puberty; Priapism |

| ATC code | L02BB |

| Biological target | Androgen receptor |

| Chemical class | Nonsteroidal |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

A nonsteroidal antiandrogen (NSAA) is an antiandrogen with a nonsteroidal chemical structure.[1][2][3] They are typically selective and full or silent antagonists of the androgen receptor (AR) and act by directly blocking the effects of androgens like testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT).[2][3] NSAAs are used in the treatment of androgen-dependent conditions in men and women.[2] They are the converse of steroidal antiandrogens (SAAs), which are antiandrogens that are steroids and are structurally related to testosterone.[2][3]

Medical uses

NSAAs are used in clinical medicine for the following indications:[2]

- Prostate cancer in men

- Androgen-dependent skin and hair conditions like acne, hirsutism,[4] seborrhea, and pattern hair loss (androgenic alopecia) in women

- Hyperandrogenism, such as due to polycystic ovary syndrome or congenital adrenal hyperplasia, in women

- As a component of hormone therapy for transgender women[5]

- Precocious puberty in boys

- Priapism in men

Available forms

| Generic name | Class | Type | Brand name(s) | Route(s) | Launch | Status | Hitsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoglutethimide | Nonsteroidal | Androgen synthesis inhibitor | Cytadren, Orimeten | Oral | 1960 | Availableb | 222,000 |

| Apalutamide | Nonsteroidal | AR antagonist | Erleada | Oral | 2018 | Available | 50,400 |

| Bicalutamide | Nonsteroidal | AR antagonist | Casodex | Oral | 1995 | Available | 754,000 |

| Enzalutamide | Nonsteroidal | AR antagonist | Xtandi | Oral | 2012 | Available | 328,000 |

| Flutamide | Nonsteroidal | AR antagonist | Eulexin | Oral | 1983 | Available | 712,000 |

| Ketoconazole | Nonsteroidal | Androgen synthesis inhibitor and weak AR antagonist | Nizoral, others | Oral, topical | 1981 | Available | 3,650,000 |

| Nilutamide | Nonsteroidal | AR antagonist | Anandron, Nilandron | Oral | 1987 | Available | 132,000 |

| Topilutamide | Nonsteroidal | AR antagonist | Eucapil | Topical | 2003 | Availableb | 36,300 |

| Footnotes: a = Hits = Google Search hits (as of February 2018). b = Availability limited / mostly discontinued. Class: Steroidal = Steroidal antiandrogen. Nonsteroidal = Nonsteroidal antiandrogen. Sources: See individual articles. | |||||||

Pharmacology

Unlike SAAs, NSAAs have little or no capacity to activate the AR, show no off-target hormonal activity such as progestogenic, glucocorticoid, or antimineralocorticoid activity, and lack antigonadotropic effects.[2] For these reasons, they have improved efficacy and selectivity as antiandrogens and do not lower androgen levels, instead acting solely by directly blocking the actions of androgens at the level of their biological target, the AR.[2]

List of NSAAs

Marketed

First-generation

- Flutamide (Eulexin): Marketed for the treatment of prostate cancer and also used in the treatment of acne, hirsutism, and hyperandrogenism in women.[3][4] It has also been studied in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia.[6] Now little-used due to high incidence of elevated liver enzymes and hepatotoxicity and the availability of safer agents.

- Nilutamide (Anandron, Nilandron): Marketed for the treatment of prostate cancer.[3] Very little-used due to a high incidence of interstitial pneumonitis and high rates of several unique and unfavorable side effects such as nausea and vomiting, visual disturbances, and alcohol intolerance.

- Bicalutamide (Casodex): Marketed for the treatment of prostate cancer and also used in the treatment of hirsutism in women,[4] as a component of hormone therapy for transgender women,[5] to delay precocious puberty in boys,[7] to prevent or alleviate priapism,[8] and for other indications. It has also been studied in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia.[6] By far the most widely used NSAA, due to its favorable profile of efficacy, tolerability, and safety.

- Topilutamide (Eucapil): Also known as fluridil. Marketed as a topical medication for the treatment of pattern hair loss (androgenic alopecia) in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Limited availability and lack of an oral formulation for systemic use make it a very little-known drug.

Second-generation

- Apalutamide (Erleada): Marketed for the treatment of prostate cancer. Very similar to enzalutamide, but with reduced central nervous system distribution and hence is expected to have a reduced risk of seizures and other central side effects.

- Enzalutamide (Xtandi): Marketed for the treatment of prostate cancer. More effective than the first-generation NSAAs due to increased efficacy and potency and shows no risk of elevated liver enzymes or hepatotoxicity. However, it has a small (1%) risk of seizures and has central nervous system side effects like anxiety and insomnia due to off-target inhibition of the GABAA receptor that the first-generation NSAAs do not have. In addition, it has prominent drug interactions due to moderate to strong induction of multiple cytochrome P450 enzymes. Currently on-patent with no generic availability and hence is very expensive.

- Darolutamide (Nubeqa): Marketed for the treatment of prostate cancer. Structurally distinct from enzalutamide, apalutamide, and other NSAAs. Relative to enzalutamide and apalutamide, shows greater efficacy as an AR antagonist, improved activity against mutated AR variants in prostate cancer, little or no inhibition or induction of cytochrome P450 enzymes, and little or no central nervous system distribution. However, has a much shorter terminal half-life and lower potency.

Miscellaneous

- Cimetidine (Tagamet): An over-the-counter histamine H2 receptor antagonist that also shows very weak activity as an AR antagonist. Also inhibits cytochrome P450 enzymes and thereby inhibits hepatic estradiol metabolism and increases circulating estradiol levels. It has been investigated in the treatment of hirsutism but showed minimal effectiveness. Sometimes causes gynecomastia as a rare side effect.

Nonsteroidal androgen synthesis inhibitors like ketoconazole can also be described as "NSAAs", although the term is usually reserved to describe AR antagonists.

Not marketed

Under development

- Proxalutamide (GT-0918): A second-generation NSAA. It is under development for the treatment of prostate cancer. Similar to enzalutamide and apalutamide, but with increased efficacy as an AR antagonist, little or no central nervous system distribution, and no induction of seizures in animals.

- Seviteronel (VT-464) is a nonsteroidal androgen biosynthesis inhibitor which is under development for the treatment of prostate cancer.

Development discontinued

- Cioteronel (CPC-10997; Cyoctol, Ethocyn, X-Andron): A structurally unique first-generation NSAA. It was under development as an oral medication for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia and as a topical medication for the treatment of acne and pattern hair loss. It reached phase II and phase III clinical trials for these indications prior to discontinuation due to insufficient effectiveness.

- Inocoterone acetate (RU-38882, RU-882): A steroid-like NSAA. It was under development as a topical medication for the treatment of acne but was discontinued due to insufficient effectiveness in clinical trials.

- RU-58841 (PSK-3841, HMR-3841): A first-generation NSAA related to nilutamide. It was under development as a topical medication for the treatment of acne and pattern hair loss but its development was discontinued during phase I clinical trials.

See also

- Selective androgen receptor modulator

- N-Terminal domain antiandrogen

- Discovery and development of antiandrogens

- Nonsteroidal estrogen

References

- ^ Kolvenbag, Geert J. C. M.; Furr, Barrington J. A. (2009). "Nonsteroidal Antiandrogens". In V. Craig Jordan; Barrington J. A. Furr (eds.). Hormone Therapy in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Humana Press. pp. 347–368. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-152-7_16. ISBN 978-1-60761-471-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Singh SM, Gauthier S, Labrie F (2000). "Androgen receptor antagonists (antiandrogens): structure-activity relationships". Curr. Med. Chem. 7 (2): 211–47. doi:10.2174/0929867003375371. PMID 10637363.

- ^ a b c d e Migliari R, Muscas G, Murru M, Verdacchi T, De Benedetto G, De Angelis M (1999). "Antiandrogens: a summary review of pharmacodynamic properties and tolerability in prostate cancer therapy". Arch Ital Urol Androl. 71 (5): 293–302. PMID 10673793.

- ^ a b c Erem C (2013). "Update on idiopathic hirsutism: diagnosis and treatment". Acta Clin Belg. 68 (4): 268–74. doi:10.2143/ACB.3267. PMID 24455796. S2CID 39120534.

- ^ a b Gooren LJ (2011). "Clinical practice. Care of transsexual persons". N. Engl. J. Med. 364 (13): 1251–7. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1008161. PMID 21449788.

- ^ a b Kenny B, Ballard S, Blagg J, Fox D (1997). "Pharmacological options in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia". J. Med. Chem. 40 (9): 1293–315. doi:10.1021/jm960697s. PMID 9135028.

- ^ Reiter EO, Norjavaara E (2005). "Testotoxicosis: current viewpoint". Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 3 (2): 77–86. PMID 16361981.

- ^ Yuan J, Desouza R, Westney OL, Wang R (2008). "Insights of priapism mechanism and rationale treatment for recurrent priapism". Asian J. Androl. 10 (1): 88–101. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7262.2008.00314.x. PMID 18087648.

Further reading

- Teutsch G, Goubet F, Battmann T, Bonfils A, Bouchoux F, Cerede E, Gofflo D, Gaillard-Kelly M, Philibert D (1994). "Non-steroidal antiandrogens: synthesis and biological profile of high-affinity ligands for the androgen receptor". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 48 (1): 111–9. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(94)90257-7. PMID 8136296. S2CID 31404295.

- Singh SM, Gauthier S, Labrie F (2000). "Androgen receptor antagonists (antiandrogens): structure-activity relationships". Curr. Med. Chem. 7 (2): 211–47. doi:10.2174/0929867003375371. PMID 10637363.

- Iversen P, Melezinek I, Schmidt A (2001). "Nonsteroidal antiandrogens: a therapeutic option for patients with advanced prostate cancer who wish to retain sexual interest and function". BJU Int. 87 (1): 47–56. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.00988.x. PMID 11121992.

- Klotz L, Schellhammer P (2005). "Combined androgen blockade: the case for bicalutamide". Clin Prostate Cancer. 3 (4): 215–9. doi:10.3816/cgc.2005.n.002. PMID 15882477.

- Gao W, Kim J, Dalton JT (2006). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nonsteroidal androgen receptor ligands". Pharm. Res. 23 (8): 1641–58. doi:10.1007/s11095-006-9024-3. PMC 2072875. PMID 16841196.

- Kolvenbag, Geert J. C. M.; Furr, Barrington J. A. (2009). "Nonsteroidal Antiandrogens". In V. Craig Jordan; Barrington J. A. Furr (eds.). Hormone Therapy in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Humana Press. pp. 347–368. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-152-7_16. ISBN 978-1-60761-471-5.

- Liu B, Su L, Geng J, Liu J, Zhao G (2010). "Developments in nonsteroidal antiandrogens targeting the androgen receptor". ChemMedChem. 5 (10): 1651–61. doi:10.1002/cmdc.201000259. PMID 20853390. S2CID 23228778.

- Kunath F, Grobe HR, Rücker G, Motschall E, Antes G, Dahm P, Wullich B, Meerpohl JJ (2015). "Non-steroidal antiandrogen monotherapy compared with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists or surgical castration monotherapy for advanced prostate cancer: a Cochrane systematic review". BJU Int. 116 (1): 30–6. doi:10.1111/bju.13026. PMID 25523493. S2CID 26204957.

- Kaur P, Khatik GL (2016). "Advancements in Non-steroidal Antiandrogens as Potential Therapeutic Agents for the Treatment of Prostate Cancer". Mini Rev Med Chem. 16 (7): 531–46. doi:10.2174/1389557516666160118112448. PMID 26776222.

External links

Media related to Nonsteroidal antiandrogens at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nonsteroidal antiandrogens at Wikimedia Commons